Feake Hills, Crooked Waters - Repetition

Open in browser

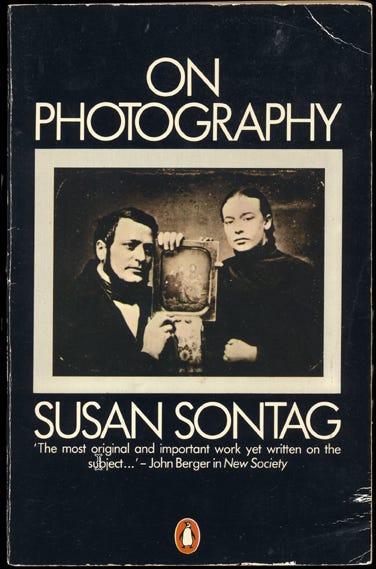

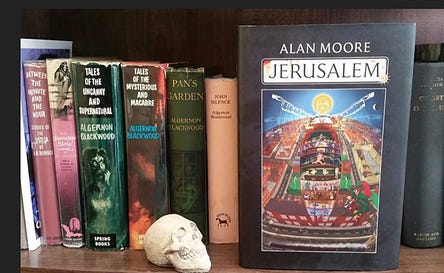

The StartIt’s a funny thing about repetition — it’s great, but sometimes it can quite suddenly cross a threshold and become “too much.” The pulse of loud music is a good example; I can be enjoying it and then for some reason, I’ve had enough. I seldom see the threshold approaching. Maybe there isn’t anything approaching in the sense of a gradual buildup. Maybe it’s just a discontinuous event. Which, of course, is the exact opposite of repetition. Strange. There are more and more electric cars around, and that means the sound of a powerful internal combustion engine might become a rare thing. It’s the sound of repetition; a drone of individual explosions so frequent it turns into one continuous sound, beloved by gearheads (or petrol heads, car geeks, etc) everywhere. If we do end up in a mostly-electric-vehicle world, I wonder if toddlers will still make “vroom vroom” noises playing with their hot wheels. Repetition is so embedded in us, and our world, that it’s almost startling to find something that doesn’t repeat. The number pi, for example — an endless series of digits that don’t repeat. Pi has been puzzled over for centuries; and stories have been written about it. Calculate it out far enough and a mysterious message appears, written into the universe itself, but hidden from us until we get clever enough to find it. Real life has roared right past those stories, as it does. We’re up to 68 trillion digits by now and no secret messages. Not that anybody’s noticed so far, at least. Did I mention that this issue is about repetition? I probably did, but what better place to repeat myself. I hope you like it. PhotographyI’m drawn to repeating forms when I’m looking for a subject to photograph. Simple tools and things made to be inexpensive but durable are good bets. Repeated simplicity is a powerful idea, and the visual expression of it can be a powerful image. Some color helps too, of course. This is a pile of commercial fishing gear — lobstering, I think — in Rockport, Massachusetts in 2017. Another iPhone image. I often say I will never understand photography. Let me explain what I mean. It’s not the actual processes. I used to use a darkroom, and I have a basic grasp of how digital photography works. I even have a not-very-developed sense of composition, light, and color. What I don’t get is what photography actually is. Susan Sontag, in her collection On Photography, points out (as I understand it) that photography stands between us and experience. You can experience something, or you can photograph it, but not both. I feel something similar to that when I use a camera. It’s why I don’t like photographing people; there’s something about it that feels voyeuristic to me. I don’t mean there’s anything wrong with photographing people — if you can do it, more power to you. But it feels wrong for me. I have, of course, photographed people. It feels okay to me when there’s an agreement between the subject and the photographer (me). A portrait, for example. That context makes it clear that the subject is projecting some kind of image they choose, and I’m recording it for them. Family photos feel okay as well; there’s a deep and complex network of understandings and agreements among families that can account for taking photos, even candid shots — which are the sort that can bother me the most. Another thing I don’t understand about photography is the relationship of a photograph — and this can be any photo, not necessarily of people — to time. Time is strange stuff that I think about a lot. Alan Moore has described a relationship with time as a solid, where you (or more precisely the angel in his novel Jerusalem) can perceive and access a moment of time simply as a kind of location, as if it’s fixed in a block of lucite. Your whole life is in there, fixed and unmoving; each instant is a place. Is that what photography is all about? Did anyone — could anyone — visualize time in that way before photography? Sontag held that the existence of photography has changed us, and how we think and perceive. That’s what I’m still struggling to understand. Tales From the ForestPorcupine proudly held up what looked like a piece of cloth. “Look at this,” she said, “I made it myself!” Hare, Dog, and Magpie nodded appreciatively. “How’d you make it?” asked Magpie. “Knitting!” said Porcupine. “Beaver lent me a book with instructions. In the book they use things called ‘needles’, but I just use a couple of quills. Since I have so many extra, you know.” Dog peered at the cloth as Porcupine held it up. “Are those sticks supposed to be part of it?” she asked. “Oh yes,” said Porcupine. “Magpie, you’ll remember about this. I was having trouble getting anywhere with my new hobby, and you told me about that old saying ‘sticks in the knitting.’ As soon as I started putting those sticks in my projects, it was easier to get them done.” “Er, Porcupine…” Magpie began. “What?” “Um…oh never mind,” said Magpie, remembering that Porcupine couldn’t hear very well. “Sticks IN the knitting it is. So this one is finished?” “Not this one,” said Porcupine. “There’s something different about this one. No matter how much work I do on it, it never seems to be quite complete.” “What is it?” asked Hare. “It’s a thing called a girdle,” said Porcupine. “You wear it, and then you look more like Otter.” “Why would you want to look more like Otter?” asked Hare. “I didn’t say you’d want to,” said Porcupine, “I just said you would. But it’s never done.” “Hmmm…” said Dog, “If you made another one of those, could you finish it?” “That’s just it,” said Porcupine, “I got the idea from another one of Beaver’s books. It had a picture of a girdle, and it looked easy to make, so I tried it. But I could never finish it. This is the fourth one I’ve worked on, and not one of them is complete. All my other projects get done just like you’d expect.” “Oh,” said Magpie, “I know what your problem is, Porcupine. It’s because it’s a girdle. Those can never be finished.” “Why not?” asked Porcupine. “I’m not really sure,” said Magpie, “but when I was perched in the college the other day, I heard some people talking about it. I don’t think they really know either, because they just called it a theory.” “A theory?” yawned Dog. “Right,” said Magpie, “something about incompleteness, and it had to do with girdles. My advice, Porcupine, is to knit hats and scarves instead.” Porcupine grinned. “That’s a good idea, Magpie,” she said. “Would you like a hat and scarf for the winter?” “Why not,” said Magpie. “As long as you finish them.” Wash. Rinse. Repeat.I recently attended a military ritual — it was a group of veterans honoring one particular veteran. The power of it, like the power of any ritual, came from the repetition of the same series of actions. Probably because it was a military ritual, the repetition was precise, and the people involved were concentrating as hard as they could on acting exactly according to form. They would do this the same way this time that they had before — and they’ve been repeating it monthly for over thirty years. That’s the thing about repetition — or at least it’s a thing about repetition. The more it cycles around and repeats, the more significant each iteration can become. Not in every case, of course — but in the case of rituals, definitely. Repetition is at the heart of the industrial society we inhabit as well. Every car tooling down the road is a schematic landscape of repetition, from the repeating actions of pistons to cams to innumerable gears and wheels. We don’t think about those in any particular way until, maybe, one specific auto reaches a milestone of repetition. Back in the day it used to be 100,000 miles, which was considered quite the accomplishment if you could maintain your car that long. Cars now are much better built, and 100,000 miles is nothing remarkable at all. If you have a Toyota or a Lexus it’s probably the minimum you’d expect, even with rudimentary maintenance. You have to reach a million miles to raise eyebrows now. Religious rituals derive their power from long history. That military ceremony I attended was 30 years old. But some religious ceremonies are centuries old, or more. There’s something about repeating a ritual from the deep past that’s evocative. You never see a horror movie where at the central ritual the chief bad guy gloats “I just came up with this last Tuesday, so it must be the most powerful yet.” Everyone viscerally understands that an ancient ritual has (or at least might have) some kind of power. But that’s exactly how we react to a lot of our modern world. I wouldn’t want to try to be productive with a computer from thirty years ago, no matter how much honored ritual was involved. There are electronic components that simply degrade, for one thing, and besides, you want your digital systems to communicate with all their silicon counterparts around the world. An old, out-of-date computer might be able to do that, if you had the technical skills to keep it working. A few people do, but most don’t see the point. There’s nothing the “old” can offer in that context — at least nothing we value. But the really old — the rites from a thousand or even thirty years ago — there’s something about those that can move us. Maybe it’s a defiance of time. Maybe it’s a way to say “this thing, this process, it’s fixed in amber and we can return to it. Returning to it, we can visualize time as a solid substance, and maybe we can transcend its strange power, constantly moving ahead yet leaving its roiled, confusing wake in our minds and memories. And for how long. That's the thing we most wonder. For how long. Or maybe for how deep, or how solid or how tangible. Because what is repetition, really, but turning the ephemeral tangible. Word of the DayWords take on new meanings all the time. One of them is terrific. No, I mean one of them is “terrific.” It comes from the Latin word "terrificus", which means frightening. But of course nowadays if you say something is terrific, you mean it's marvelous and not frightening at all. Something like, I don't know, this very newsletter, perhaps. And yes, perhaps not. But just wait! “Terrific” is a fairly recent addition to English; it didn’t arrive the 17th century. John Milton was the first to use it, in Paradise Lost. He meant it in the original Latin sense of frightening: "The Serpent suttl’st Beast of all the field, Of huge extent somtimes, with brazen Eyes And hairie Main terrific, though to thee Not noxious, but obedient at thy call." In that passage he's talking about a "serpent with a hairy mane", which he probably lifted from Virgil's Aeneid, where he describes two man-eating serpents that way (sort of). As an aside, Virgil's serpents weren't snakes; they were more like some sort of sea monsters. "Terrific" began a slow shift in meaning right away, driven by its metaphoric use by other writers. In 1743 Matthew Tower described a mythical giant (Porphryion, if you must know) as "of terrific size". What he's doing there is using the original “frightening” as a way to amplify “size.” He could have just said the giant himself was terrific. Thomas Dutton did the same thing in 1798 when he wrote "I am struck with admiration at the terrific sublimity of his genius." Now “terrific” is modifying “sublimity;” an even clearer application of the word as a metaphoric amplifier. In the following century terrific continued its advance into metaphorical use by showing up in advertising. In 1871 an ad in Athenaeum magazine included this: "The last lines of the first ballad are simply terrific, — Something entirely different to what any English author Would dream of, much less put on paper." Another aside: notice that in 1871 it was apparently more common to say "different to" rather than "different from". Both of these are used today, "to" more in the UK, and "from" more in the US. Returning to “terrific," the word was already being used as a standalone based on its metaphoric use instead of its original meaning. That approach spread at, well, terrific speed. In 1930 Denis Mackail published The Young Livingstones and included this: "Thanks awfully," said Rex. "That'll be ripping.'' "Fine!" Said Derek Yardley. "Great! Terrific!" So there you have it. From frightening, deadly sea monsters to an enthusiastic exclamation in just just three hundred years. That’s terrific! If you liked this issue of Feake Hills, Crooked Waters, please share it! |

Older messages

The issue with numbers

Monday, May 30, 2022

You can count on it — but should you?

It’s All the Rage

Monday, May 30, 2022

But what do you do with it?

You Might Also Like

The Tortoise and The Hare: The Art Market Edition

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Your weekly 5-minute read with timeless ideas on art and creativity intersecting with business and life͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Unexpectedly at home

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Billy stomps in the door from the bus stop. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

A Whopper of a Way to Pay For Your Wedding

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Maybe it'll happen again if Jim Olive and Jane Garden get married?

Community Tickets: Advanced Scrum Master (PSM II) Class of March 26-27, 2025

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Save 50 % on the Regular Price ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

eBook & Paperback • Demystifying Hospice: The Secrets to Navigating End-of-Life Care by Barbara Petersen

Monday, March 3, 2025

Author Spots • Kindle • Paperback Welcome to ContentMo's Book of the Day "Barbara

How Homer Simpson's Comical Gluttony Saved Lives

Monday, March 3, 2025

But not Ozzie Smith's. He's still lost, right?

🧙♂️ Why I Ditched Facebook and Thinkific for Circle (Business Deep Dive)

Monday, March 3, 2025

Plus Chad's $50k WIN ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

I'd like to buy Stripe shares

Monday, March 3, 2025

Hi all, I'm interested in buying Stripe shares. If you know anyone who's interested in selling I'd love an intro. I'm open to buying direct shares or via an SPV (0/0 structure, no

What GenAI is doing to the Content Quality Bell Curve

Monday, March 3, 2025

Generative AI makes it easy to create mediocre content at scale. That means, most of the web will become mediocre content, and you need to work harder to stand out. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

mRNA breakthrough for cancer treatment, AI of the week, Commitment

Monday, March 3, 2025

A revolutionary mRNA breakthrough could redefine medicine by making treatments more effective, durable, and precise; AI sees major leaps with emotional speech, video generation, and smarter models; and