Your Book Review: The Dawn Of Everything

ON ROUSSEAU, ESSAY CONTESTS, POLITICAL MOTIVATIONS FOR REVISITING THE ORIGIN OF HUMAN CIVILIZATION, AND THE BOOK IS INTRODUCEDThe original hunter-gatherer tribes are often reasoned about via the analogy of contemporary hunter-gatherer tribes (or at least, those in recent history surveyed by anthropologists). Yet which tribe is an “appropriate” analogy changes depending whether the reasoner is a follower of Hobbes or Rousseau; a modern Hobbesian might prefer to use the war-like Yanomami as the analogy, whereas a follower of Rousseau might prefer the more peaceful and egalitarian Hadza, Pygmies, or !Kung.

So for the Davids, the question is not, as it was for Rousseau, “How did inequality arise?” but rather, given the diversity of prehistorical ways of life, “How did we get stuck with the inequalities we have?” This is a very interesting question to ask and the Davids marshal a veritable trove of evidence, some of which really does convincingly support their theses. But there is a problem with the book. For their own version of prehistory is corrupted by politics, the same corruption they accuse Rousseau and Hobbes and other thinkers of falling prey to before them. After all, the Davids’ express purpose is to argue that humans, in their diverse forms of prehistorical governments, are free, even playful, and capable of imagining new ways of living and consciously choosing to live in these ways, which the authors take to imply that radical progressivism, or post-capitalism, might be successful in our modern world—and moreso, that it implies our current world and its ills are, in turn, a choice. The Davids don’t hide their progressive goals, either in the book or in interviews, and their political leanings are evident from the way it’s written as well: their sensitivity to social justice spins throughout like a finely-tuned gyroscope. This often leads to blanket statements, like how Western civilization is currently great “except if you’re Black,” or even outright misrepresentations of their opponents, like assigning to Steven Pinker the claim that “all significant forms of human progress before the twentieth-century can be attributed only to that one group of humans who used to refer to themselves as ‘the white race’” (Pinker definitely doesn’t claim this), or rejecting kinship-based scientific theories of altruism with reasoning like “many humans just don’t like their families very much” (these are all real quotes). Somewhere, within the morass of innuendo and political leanings, as well as the truly encyclopedic display of archeological and anthropological knowledge, there is a truth as to how humans lived prehistorically, and how civilization, with all its ills (and its goods) came to be. But what is that truth? THE AGRICULTURE REVOLUTION WAS NO REVOLUTION, NOR DID IT INEXORABLY LEAD TO INEQUALITY; INEQUALITY, EVEN CHATTEL SLAVERY, ALREADY EXISTED

And with this the Davids begin their dissection of the idea that agriculture was the root cause of political inequality, arguing that agriculture was not actually a “revolution” that irrevocably changed how humans lived. Instead, the Davids present a wave of evidence that pre-agricultural hunter-gatherer societies could be incredibly politically diverse, and, sometimes, rival the worst atrocities of modern societies; at other times, they could rival their best. They zoom into the Native American foragers (not farmers) who lived on the California coastline, and observe substantial political differentiation, even out thousands of years into the past. Particularly between the Yurok in California and their northern neighbors of the Northwest Coast. The Yurok

Compare that to the Native Americans of the Northwest Coast, right above them:

The Yurok and other micro-nations to the south only rarely practiced chattel slavery. In stark contrast,

Indeed, there is evidence of Native American chattel slavery that goes back to 1850 BC in Northwest Coast societies (again, these are not agricultural societies).

So we have slave-owning Mafia dons to the north, and meanwhile, ascetics to the south. Despite both being foragers, they ate extremely different diets, with Californian tribes relying on nuts and acorns, while the Northwest Coast societies were sometimes referred to as ‘fisher-kings’ (presumably due to their two loves: aristocracy and fish). As the Davids say,

Furthermore, the Davids make a good case that agriculture was not the sort of parasitic memetic invasion it is often portrayed as by writers like Yuval Noah Harari.

Instead

This is despite the fact that scientific experiments on wheat genetics have revealed that

So if it was a revolution, it was one that occurred as slowly as almost all of post-literate human history combined. And not only that, but prehistorical societies seem to develop agriculture and then consciously abandon it, preferring some other way of life. The Davids give several examples of this, including the builders of Stonehenge, who

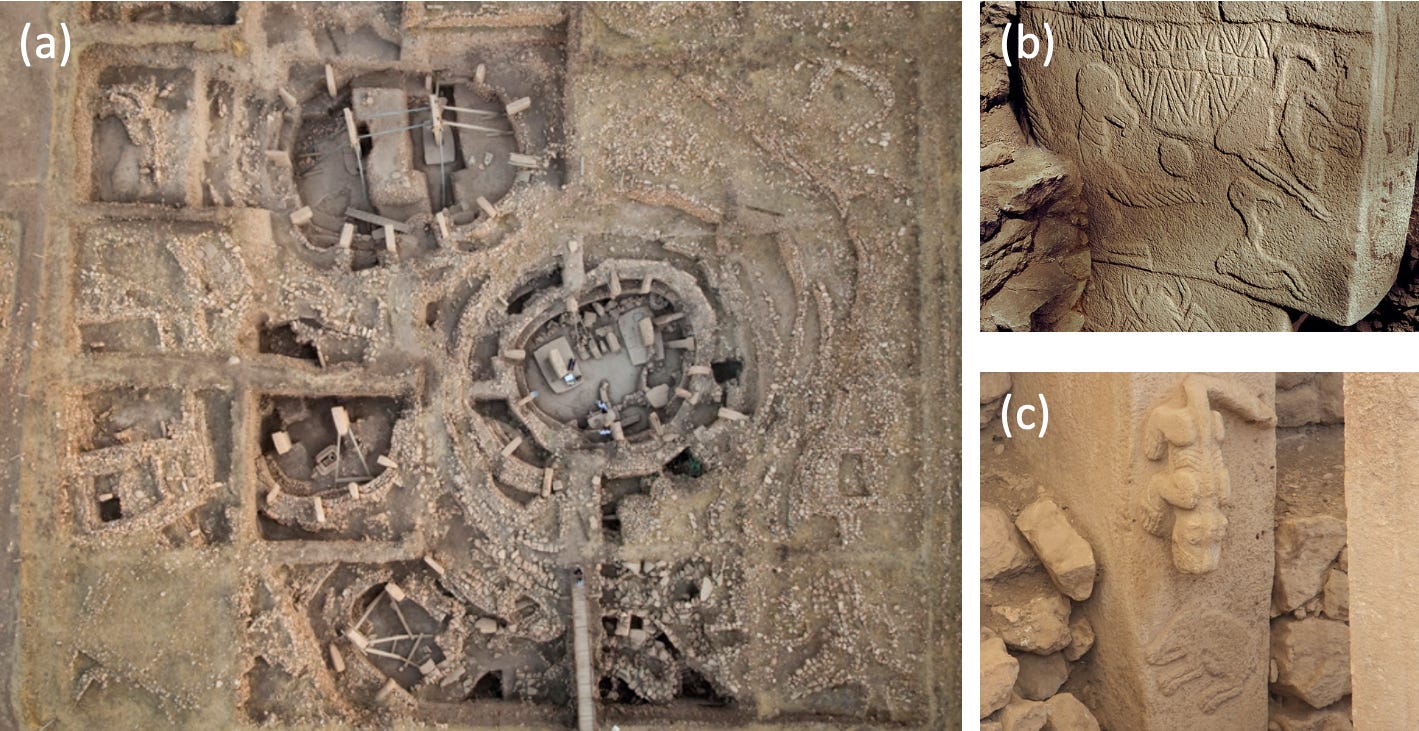

This sort of laissez-faire attitude toward farming is true in many other places, for example, in the early Amazonia there are seasonal cycles in and out of farming, and same for the habit of keeping pets but not domesticating animals fully, i.e., people who were neither forager or farmer, and often for thousands of years. Nor did the agricultural revolution, even as it was occurring, result in one way of living; it seems like during the transition toward farming very different societies were possible, even those that lived in proximity to one another, the exact same as hunter-gatherer societies. Consider the upland and lowland sectors of the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East; sectors which are themselves demarcated by Göbekli Tepe, the world’s oldest construction of stone megaliths, dated to around 9,000 BC. Between the upland and lowland sectors we see, again, political differentiation. North of Göbekli Tepe, in the upland, there was a city wherein at

In comparison, lowland villages of the Fertile Crescent also attached a great importance to human heads, but treat them in an altogether different manner, in a way one might describe as touching (despite its macabre nature), like the ‘skull portraits’ found in lowland Early Neolithic villages.

Such details in art and priorities corresponded to political differences: the upland sectors of the Fertile Crescent were

And yet we know that the regions traded with one another. There are plenty of other examples of political differentiation, both pre- and post-agriculture, although even the Davids are forced to admit that agriculture marks a change. Eventually it

But the fact that humans were able to invent, and then abandon, agriculture, and have inequality or equality to greater degrees throughout the invention of agriculture, and to continue to have political differentiation after agriculture, all suggests to the Davids that our ancestors, despite (as one might say) having the handicap of living in prehistory, were choosing to live a certain way, not simply driven like automata by environmental inputs or new inventions. They made conscious political choices, just like us. CONSCIOUS POLITICAL CHOICE AMONG NATIVE AMERICANS AND THE “INDIGENOUS CRITIQUE” OF WESTERN CIVILIZATIONThis thesis may sound surprising, but the Davids bemoan that this is because non-Western, non-European civilizations are consistently stripped of political self-consciousness in standard historical accounts, e.g.,

The conversational nature of the Wendat government led to most Jesuits describing French-speaking Native Americans as highly eloquent, as, at least among those who spoke Iroquoian languages, open conversation and debate were how tribe decisions got made, a process that rewarded the more eloquent and convincing of its members (although not all Native American states valued the reasonable debate of the Iroquois). But somehow the self-consciously political nature of New France was replaced by either the idealized fantasies of Rousseau or the idealized barbarism of Hobbes. The Davids have a story for how that happened, and it actually involves Kandiaronk. They argue that Native American intellectuals were the true originators of many of the criticisms of the Western World that would go on to define the political Left, and European intellectuals in turn co-opted their criticisms, using fictional Native Americans as mouthpieces, while the originals were forgotten to mainstream history. This is because Native American intellectuals,

The reality was quite different, the Davids suggest, once you investigate evidence from the Great Lakes region where tribes like the Wendat, and Jesuits and fur traders, all mixed together. In the late 1600s, Lahontan, a French aristocrat, spent much time in New France, and there met the Kandiaronk (also called ‘Le Rat’, since his name meant ‘muskrat’). Kandiaronk was

But for a long time the dominant historical view was that Lahontan essentially created a fictional character (with intimate knowledge of European life and customs) to use as a convincing mouthpiece to give European critiques of European culture. Except that actually the pieces fit much better because Lahontan was, perhaps with only some exaggeration, writing the real Kandiaronk. This is attested to by Lahontan himself, who claims to have based it off of him, and is backed up by lost historical details like how outside accounts attest that Kondiaronk was indeed invited to debates comparing European life to indigenous life, and also how

Judging this, I have to say I think the Davids are correct; there is a good case that there were real and serious intellectual contributions from Native Americans in critiquing the inequalities of European civilization, particularly from the articulate and debate-based Iroquoian-speaking nations.

Really? In medieval Europe, the role of wealth in the clergy was fractious and constant. And Christ, the most important intellectual figure for medieval Europe, was himself a political radical and revolutionary, overturning the tables of the moneylenders and frequently espousing things like in Matthew 20:25-28:

What is that if not a statement of disgust at social inequality? And not for the only time in the book, the Davids undercut themselves when they later point out that the conception of inequality was alive and well in European peasantry:

So in their overly confident conclusion, the Davids end up pushing a progressive mirror to the conservative take that all the good aspects of the Western world are based entirely on the Christian tradition; the mirror the Davids offer up is that the progressive politics of the Enlightenment are based entirely on the indigenous critique. ON SEASONALITY AND THE “THEATRICAL” GOVERNMENTS OF PREHISTORICAL SOCIETIES, AS WELL AS THEIR CAREFUL BURIAL OF ABNORMAL INDIVIDUALSOne of the defining features of prehistoric humanity seems to be their dynamism and ever-changing nature. Even at the times when they are building monuments, things we would think of as “early civilization” like Stonehenge or Göbekli Tepe, it is often not permanent, but rather as celebrations, markers, or otherwise abandoned structures for much of the year. For instance, at Göbekli Tepe:

This seasonality also shows up in anthropologist accounts of hunter-gatherer societies. The Davids quote from a 1903 book on seasonal variations among the Inuit, describing how during the summer,

One might reasonably ask whether this was all responding solely to environmental concerns: altruistic during periods of being flush with resources, despotic during periods of scarcity. But that’s not what we see. Among the Kwakiutl of the Northwest Coast of Canada

Which brings up why an early hierarchical government, like an aristocracy, capable of moving gigantic stones, or coordinating large hunts and storing food, would give up its authority in the off-season so easily—if there were rulers of these people, they did not have the sort of authority those in written history do, for

The Davids suggest that for much of prehistory seasonality ruled, as if humans were seeing what fit, playing along, and under such structures formal authority was a wispy, changeable, seasonal, almost humorous thing. And various techniques kept formal authority from ever becoming too real. For instance, the Native Americans of the Plains would

Of course, it might be easier to see how prehistorical societies worked if they buried more of their dead. Instead:

But we see some of the weirdness of humans, their political diversity, peeking through. In an oddity of rich Upper Paleolithic burials

Such unexpected incongruities humanize our ancestors—perhaps we sometimes buried favored clowns rather than favored kings. So yes, I think the Davids are right on this as well: there is at least suggestive evidence of a period of time, particularly around or right after 10,000 BC, of what might be called political experimentation by prehistorical humans. These nascent governments and formal systems of law and order might not have been taken all that seriously at first, more theatrical and seasonal in nature, until, slowly, as John Updike said, “the mask eats the face.” THE SAPIENT PARADOX AS AN ANCIENT ANALOG TO THE FERMI PARADOX, AND THE GREAT TRAP OF PREHISTORY IT IMPLIESAlmost everything we’ve talked about so far, with the exception of the mammoth houses and some remains of gathering places, takes place after 10,000 BC. It’s really only in the Upper Paleolithic (12,000-5,000 BC) that there is any good evidence for what we would call civilization, with its associated lavish burials and monumental centers of ritual congregation and pilgrimage and trade networks and specialization of tribes toward certain industries, and it is only at this point that complex representation in art becomes essentially universal.

And also how

They speculate there is undiscovered complex representational cave art in Africa that goes back equally far. This claim is based on how

In another example of willful ignorance on this issue, the Davids ask:

The answer they give (in fact, the Davids barely give it, they sort of vaguely imply) is that the advent of farming was due to the ending of the Ice Age and retreat of the glaciers. But this is in direct contradiction to a bunch of their previous points around farming, like how the post-Ice Age was actually a “Golden Age” for foragers, that early farming in general was done in more extreme environmental conditions and was often even an act of desperation, that agriculture was easy to discover and evolve as a technology, and that it was a natural, almost inevitable, outcome of the caring relationship hunter-gatherers had with the land. So the Davids leave the Sapient Paradox unexplained. Of course, the Davids might simply say that there was civilization from the beginning, but their evidence for this would be nonexistent; even they admit there is a cut-off

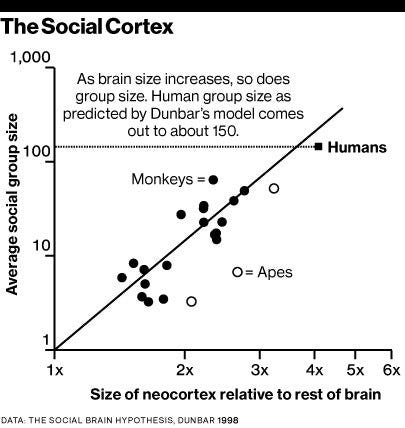

That is, if the cavalcade of cultures that the Davids posit stretched back further than the 12,000 BC boundary of the Upper Neolithic, there would surely be some evidence—prehistorical societies, in their experimentation with different forms of organization and life, would leave traces of their divergences, or inventions of different technologies and art, i.e., all the myriad things we see humans do during the time of political experimentation that the Davids do have, at minimum, suggestive evidence for. Instead, everyone was silent for tens of thousands of years. And it’s this silence, just like the silence of the stars, that is striking. The question becomes: How were the silent people before the Upper Neolithic living, and also, what accounts for this efflorescence in culture and ways of living in the Upper Neolithic? The work of Robin Dunbar seems important here, somehow, although no two thinkers on these topics use it in the exact same way. Dunbar’s number is the idea that humans can hold around 150 distinct social relationships in mind at any one time, and that this is a function of their cortex size, for, in primates, the greater the neocortex the larger the average social group size. It seems there’s likely something special about Dunbar’s number being violated—after all, a lot of the Upper Neolithic revolution is occurring when groups of humans (in the few hundreds) are getting together seasonally into much larger groups, making pilgrimages, joining, and then dispersing. Each theory might have a different relationship to Dunbar’s number; for the followers of Rousseau, past Dunbar’s number egalitarianism begins to break down, and therefore the terrible necessity of the inventions of hierarchy, state, and bureaucracy. Even the Davids admit that the violation of the Dunbar number is likely important, writing we should

IN WHICH AN ALTERNATIVE HYPOTHESIS FOR THE INITIAL CONDITION OF PREHISTORY IS PROPOSED, AND AN EXPLANATION OF THE GREAT TRAP OF HUMAN HISTORY IS GIVENIf we imagine being transported back to 50,000 BC, what would we expect to find? In the end, we have to give a metaphor to current life of how things were organized: a follower of Rousseau would expect Burning Man, a follower of Hobbes might expect to find a bunch of warring gangs, the Davids might expect to find the deliberation of a town council full of Kandiaronks. But perhaps small groups of humans less than the Dunbar number were organized by none of these, since they didn’t need to be—instead, they could be organized via raw social power. That is, you don’t need a formal chief, nor an official council, nor laws or judges. You just need popular people and unpopular people. After, who sits with who is something that comes incredibly naturally to humans—it is our point of greatest anxiety and subject to our constant management. This is extremely similar to the grooming hierarchies of primates, and, presumably, our hominid ancestors. So 50,000 BC might be a little more like a high school than anything else.  After all, in high school there is a clear social web but no formal hierarchies. And while there is a social hierarchy, it’s not ordinal—you couldn’t list, mathematically, all the people from least to most popular, like you could with a formal hierarchy. It’s more like everything is organized by raw social power, that is, there is constant and ever-shifting reputational management, all against all. And there’s actually a lot of evidence, even just in what the Davids introduce, that fits with the idea that our initial condition was something like anarchist bands organized by raw social power only. Because it sure looks like being popular was the primary concern for prehistorical societies, at least if we use the same evidence the Davids do. In 1642, the Jesuit missionary Le Jeune described this phenomenon of a lack of all formal power among the Montagnais-Naskapi, who anthropologists normally consider “egalitarian” bands of hunter-gatherers:

In fact, chiefs were basically just the most popular people, nothing more, for instance, in Northwest Coast Native Americans a high-status male

The same lack of formal power but attention to popularity was true across America, even in Kandiaronk’s tribe.

And similarly:

That is, material resources were worth almost nothing, all that mattered was the social pressure you could apply. This is true even for things like crime, which was prevented not by a system of laws, but by a system of social pressure, wherein the guilty were not punished but rather their lineage or clan had to pay compensation (implying that that the anger of one’s lineage or clan would be enough to not lead to recidivism for offenders). This system of social power to prevent crime was highly effective in its implementation, as the Davids describe the Jesuit Le Jeune grudgingly admitting. It may even be that money, rather than being invented to keep track of trade relationships or debts for private property, was invented to keep track of social relationships instead. For example, consider again the Yurok, who inhabited the northwestern corner of California, and note that

And this fits with the theatricality and seasonality that the Davids make so much of, like in the case of Native American tribes, wherein

It’s almost tautological that early societies had to be organized by raw social power—there are no formal powers to enforce anything else, nor combat social pressure when it’s applied (and humans will always apply it). It also explains why early formal governments are theatrical or seasonal, since they are merely a mask of raw social power—which families are important, which are liked, who’s friends, who’s frenemies, who’s enemies—i.e., what the Davids assume is a set of constantly shifting Neolithic “political experiments” is really just a bunch of constantly shifting mores that, like the Gestapo, hide the real power. Which was who was popular and who was not. Heck, the high school metaphor (despite admittedly not being perfect) does a better job than other metaphors of explaining the odd evidence that skeletons given the honor of burials in the Upper Palaeolithic were often dwarfs or giants or bore physical anomalies: they were mascots.

And the evolutionary anthropologist Christopher Boehm came to a similar conclusion:

In Haiti, G.E. Simpson found that a peasant will seek to disguise his true economic position by purchasing several smaller fields rather than one larger piece of land. For the same reason he will not wear good clothes. He does this intentionally to protect himself against the envious black magic of his neighbors. But it never seems to strike Dunbar or others that living under a dominion of raw social power, with few to little formal powers anywhere, would be hellish to a citizen of the 21st century (which is why I say the closest analog is high school). My mother used to quote Eleanor Roosevelt all the time:

And this explains why violating the Dunbar number forces you to invent civilization—at a certain size (possibly a lot larger than the actual Dunbar number) you simply can’t organize society using the non-ordinal natural social hierarchy of humans. Eventually, you need to create formal structures, which at first are seasonal and changeable and sort of theatrical, and take all sorts of diverse forms, since the initial condition is just who’s popular. But then these formal systems slowly become real. So then what is civilization? It is a superstructure that levels leveling mechanisms, freeing us from the Gossip Trap. For what are the hallmarks of civilization? I’d venture to say: immunity to gossip. Are not our paragons of civilization figures like Supreme Court justices or tenured professors, or protected classes with impunity to speak and present new ideas, like journalists or scientists? ON THE TECHNOLOGICAL RESURRECTION OF THE GOSSIP TRAP AND THE DEVOLUTION OF CIVILIZATION YOU’VE BEEN NOTICINGA lot of things change as you age, but one that’s particularly strange is finding hairs in weird places. Like your inner ears. It turns out this is because aging is basically genetic confusion, down at the molecular level. As they age, cells get mixed up as to what sort of cell they’re supposed to be. And there’s a lot of ancient instructions, just lying around, still in your cells. Weird hair growth is the cell latching on to some ancient genetic instruction. Our predecessors had lots of hair everywhere, your cells get confused, and you begin to manifest your hirsute ancestors. The hairy tufts springing from your grandfather’s ears are there because parts of him are literally devolving into an ancient creature. As William Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” What if there were a mental equivalent? After all, if we lived in a Gossip Trap for the majority of our existence as humans, then what would it be, mentally, to atavistically return to the gossip trap? Well, it sure would look a lot like Twitter. Which means that, with the advent of social media, and the resultant triumph of the spread of gossip over Dunbar’s number, we might have just inadvertently performed the equivalent of summoning an Elder God. The ability to organize society through raw social power given back to a species that had to climb out of the trap of raw social power by inventing civilization. The Gossip Trap is our first Eldritch Mother, the Garrulous Gorgon With a Thousand Heads, The Beast Made Only of Sound. And if the Gossip Trap was humanity’s first form of government, and via technology it’s been resurrected once more into the world, how long until it swallows up the entire globe? IN WHICH THE TRUTH IS REVEALEDAn admittance. For it should be obvious by now: this text is corrupted. The same corruption that I accused the Davids of falling victim to, and that they, in turn, accused Rousseau and Hobbes of falling victim to. I have made the past political, and prehistory a sepia reflection of the current day. Just like Rousseau, or Hobbes, or the Davids, I have spun a yarn. I think it’s a true yarn, I really do. I think the Gossip Trap is real, or at least, explains more than the other hypotheses about prehistorical life I’ve read, and I think it’s likely we did accidentally, via social media, summon back the Elder God that is our innate form of government. And I think we should be worried about civilization itself. Maybe the ultimate truth or falsity of prehistorical narratives is unknowable. Maybe speculations such as these are only stumbling through a maze, all of human history a hall of mirrors in which we wander. And, projected in gigantic distortions all around us, we see only our own face. You’re a free subscriber to Astral Codex Ten. For the full experience, become a paid subscriber. |

Older messages

Somewhat Contra Marcus On AI Scaling

Friday, June 10, 2022

...

Against "There Are Two X-Wing Parties"

Thursday, June 9, 2022

...

Which Party Has Gotten More Extreme Faster?

Wednesday, June 8, 2022

...

My Bet: AI Size Solves Flubs

Tuesday, June 7, 2022

...

Open Thread 227

Sunday, June 5, 2022

...

You Might Also Like

How to Keep Providing Gender-Affirming Care Despite Anti-Trans Attacks

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Using lessons learned defending abortion, some providers are digging in to serve their trans patients despite legal attacks. Most Read Columbia Bent Over Backward to Appease Right-Wing, Pro-Israel

Guest Newsletter: Five Books

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Five Books features in-depth author interviews recommending five books on a theme Guest Newsletter: Five Books By Sylvia Bishop • 9 Mar 2025 View in browser View in browser Five Books features in-depth

GeekWire's Most-Read Stories of the Week

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Catch up on the top tech stories from this past week. Here are the headlines that people have been reading on GeekWire. ADVERTISEMENT GeekWire SPONSOR MESSAGE: Revisit defining moments, explore new

10 Things That Delighted Us Last Week: From Seafoam-Green Tights to June Squibb’s Laundry Basket

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Plus: Half off CosRx's Snail Mucin Essence (today only!) The Strategist Logo Every product is independently selected by editors. If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an

🥣 Cereal Of The Damned 😈

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Wall Street corrupts an affordable housing program, hopeful parents lose embryos, dangers lurk in your pantry, and more from The Lever this week. 🥣 Cereal Of The Damned 😈 By The Lever • 9 Mar 2025 View

The Sunday — March 9

Sunday, March 9, 2025

This is the Tangle Sunday Edition, a brief roundup of our independent politics coverage plus some extra features for your Sunday morning reading. What the right is doodling. Steve Kelley | Creators

☕ Chance of clouds

Sunday, March 9, 2025

What is the future of weather forecasting? March 09, 2025 View Online | Sign Up | Shop Morning Brew Presented By Fatty15 Takashi Aoyama/Getty Images BROWSING Classifieds banner image The wackiest

Federal Leakers, Egg Investigations, and the Toughest Tongue Twister

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said Friday that DHS has identified two “criminal leakers” within its ranks and will refer them to the Department of Justice for felony prosecutions. ͏ ͏ ͏

Strategic Bitcoin Reserve And Digital Asset Stockpile | White House Crypto Summit

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Trump's new executive order mandates a comprehensive accounting of federal digital asset holdings. Forbes START INVESTING • Newsletters • MyForbes Presented by Nina Bambysheva Staff Writer, Forbes

Researchers rally for science in Seattle | Rad Power Bikes CEO departs

Saturday, March 8, 2025

What Alexa+ means for Amazon and its users ADVERTISEMENT GeekWire SPONSOR MESSAGE: Revisit defining moments, explore new challenges, and get a glimpse into what lies ahead for one of the world's