Not Boring by Packy McCormick - Techbio Taxonomy

Techbio TaxonomyA guest post by Elliot Hershberg on 4 forces behind the shift from biotech ➡️ techbioWelcome to the 1,553 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! If you haven’t subscribed, join 147,020 smart, curious folks by subscribing here: Today’s post is brought to you by … Cromatic As you’ll read today, the biotech industry is evolving. Launching a new startup has become less capital intensive. A new generation of founders are building nimble teams, and outsourcing portions of their R&D to stay lean and focus on core scientific competencies. Outsourcing can come with headaches. It can be challenging to decide on the right vendor, compare prices, and track project progress. While contract research organizations (CROs) are an important part of the modern biotech ecosystem, these partnerships come at a cost. Cromatic is on a mission to help modern biotechs make the most out of outsourcing. Their vision is to develop the infrastructure necessary to make contract management a painless, daresay enjoyable, experience. Cromatic makes outsourcing easier than ever so you can focus on the science. Cromatic is currently performing outsourcing searches for early stage biotech companies for free. Learn more here. Hi friends 👋, Happy Monday! Hope you’re enjoying a relaxing August. I’d like to briefly interrupt your summer holiday to let Elliot Hershberg introduce you to the future. You met Elliot before when he wrote about Ginkgo Bioworks. While he’s not pursuing his Ph.D. in Genomics at Stanford, Elliot works with us at Not Boring Capital to discover and invest in the sci-fi-adjacent companies pushing the frontiers of biology. Why invest in biotech, you ask? You’re not alone. One of the most frequent questions I get from LPs and potential LPs is why in the world Not Boring Capital would invest in biotech. Historically, biotech has been a very specific and separate discipline from traditional venture investing. Getting a therapeutic to market is risky at best, and even if it works, it’s incredibly cash consumptive. A small fund investing in early stage biotech is bound to be diluted to smithereens by exit time. But Elliot’s thesis, of which I’ve become convinced over many conversations with both him and founders building in the space, is that there’s an enormous shift afoot in which biotech companies are beginning to look a lot like software companies did a decade or so ago, propelled by forces akin to the rise of AWS, founder-friendliness, and a growing ecosystem of primitives with which to build. Founders are getting closer and closer to programming atoms like software engineers program bits. The capital, and team size, needed to start and scale these businesses is declining. Multi-billion dollar outcomes and 100x returns are becoming more frequent. The shift is so big that the category needs a new name: from biotech to techbio. In today’s piece, Elliot synthesizes years of knowledge into a compact techbio taxonomy and describes four key shifts that are unleashing a wave of entrepreneurial energy on one of the biggest opportunities available to humanity: “tapping into the awesome power of biological growth.” BTW, if you don’t already, you need to subscribe to Elliot’s newsletter, The Century of Biology. There’s so much exciting work being done in techbio, and there’s no better guide than a triple-threat researcher, investor, writer. Let’s get to it. Techbio TaxonomyAn Elliot Hershberg Guest Post for Not Boring Sometimes new words and terminology are necessary before we can fully internalize the change taking place around us. We needed the notion of the World Wide Web before we could truly capitalize on the promise of a global network of computers. Today, Web3 is a term that encompasses a broad set of ideas about where the Internet should go next. An important transition is also taking place in the world of biotech. From the headline news of Google DeepMind solving protein structure prediction, to the recent completion of the human genome, the frontier of biology has become deeply integrated with AI, software, and hardware. The new generation of hybrid companies on the cutting edge of this trend are often referred to as techbio companies. This new intersection between bits and atoms is a really big deal. In a world where the cost of developing new drugs is increasing exponentially and healthcare takes up an unsustainable portion of our GDP, something needs to change. Beyond developing more medicines cheaper and faster, techbio could help us live longer and healthier lives in material abundance made possible through the biologization of our industrial processes. But what actually is a techbio company? What are the defining characteristics of this new category? Here, I will attempt to contribute to the challenging and highly imperfect science of taxonomy by answering this question. With new words and terms, there needs to also be a shared understanding of what they mean. As the first generation of techbio companies mature and the ecosystem evolves, patterns are beginning to emerge. The techbio companies of tomorrow will likely be:

It’s time to unpack each of these components. Let’s jump in! 🧬 Founder-led 🧑🔬🥼In the world of tech, a movement focusing on “founder-led startups” would seem redundant and obvious. Of course founders lead startups, who else would? However, this wasn’t always the case. In the era before nearly all VCs touted themselves as “founder friendly” there was a very different approach to company creation and management. Well before the existence of the YC library, AngelList, and other resources that underpin the modern startup ecosystem, VC looked very different from what it is today. In 1972, just one year after the term “Silicon Valley” was coined, Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield & Byers became the world’s largest venture capital partnership after raising an $8 million dollar fund. This new fund was born directly out of two of the most important companies in Silicon Valley history.

Gene Kleiner was one of the iconic Traitorous Eight employees who decided to leave the Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory to found Fairchild Semiconductor. His new partner Tom Perkins had learned directly from David Packard at HP. When they joined forces to start a fund, venture capital was still a nascent practice. There was no such thing as deal flow for VCs. According to Kleiner, “We just didn’t wait around for deals to come to us. You had to create the deals to be really successful.” In practice, this meant partnering with university professors or entrepreneurs from existing large companies, and taking active management positions in the new ventures. An example of this is Tandem Computers, one of the fund’s early wins. The company sold fault-tolerant computer systems. The CEO was Jimmy Treybig, a former HP colleague. Tom Perkins served as the chairman of the company from when it was founded until a merger over 20 years later. Obviously, a lot has changed in the 50 years since Kleiner Perkins first opened its doors on Sand Hill Road. The computer industry has exploded, giving birth to the software industry and the Web. With each generation, founders have gotten younger and companies have become more massive. While the first founders of Kleiner Perkins portfolio companies were former colleagues with deep roots in the early computer industry, the list now includes Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the brilliant young computer scientists who dropped out of their PhDs at Stanford to found Google. The trend hasn’t stopped there. A more recent Kleiner Perkins investment is Figma, the popular design tool that Packaso McCormick uses to make graphics for Not Boring. They have delivered on their early vision of building a tool that would “allow users to creatively express themselves online.” Figma was founded by Dylan Field and Evan Wallace who met while undergrads at Brown. Dylan was awarded the Thiel Fellowship to drop out of college and work on Figma full time. A 2013 TechCrunch article covering Figma’s $3.8 million seed round summed it up nicely saying, “Children are our future, and VCs are giving them the cash to make it happen.” A lot had to happen for tech to reach this stage. Computers had to become substantially cheaper, faster, and more widespread. An enormous amount of engineering had to happen to make computer science more accessible and standardized. Programming languages had to evolve to more closely approximate natural language, encapsulating lower level details with clever abstractions. Modern browsers are so complex that even brilliant programmers like John Carmack struggle to keep track of all of the steps involved in rendering the text you’re reading now. But browsers have a crucial property: they provide a nearly universal platform that can be used to build new platforms. The browser was the core platform that enabled two brilliant young people to launch a company providing a new platform for creative expression. It took several layers of platforms to launch The Great Online Game. In most cases, biotech company creation looks nothing like the current paradigm in tech. Current biotech venture capital much more closely resembles the state of affairs 50 years ago when Kleiner Perkins was founded. The first generation of specialist biotech investors followed a similar playbook to the Tandem Computers days. The process involved identifying promising science from academic labs and building out a management team to commercialize it, with venture capitalists often taking an active role. More recently, this process has been systematized by venture creation funds and companies. Some of the funds most commonly associated with this strategy are Atlas, Third Rock, and Flagship, which are all based in the Boston area. While there is variability in the mechanics between these types of funds, the core practice is the same: new companies are internally ideated, financed, and incubated within the walls of VC funds. There are two major challenges associated with this model:

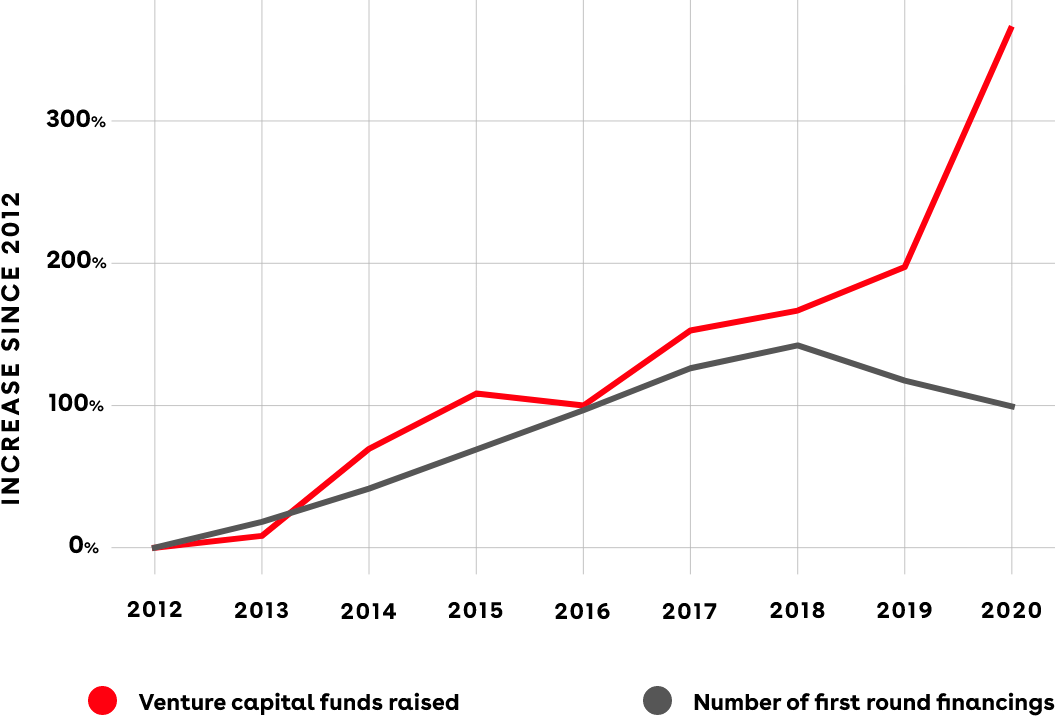

While the Web startup ecosystem has rapidly expanded, company creation in biotech has actually slowed down:

Part of this trend can be explained by the fixed scaling properties of venture creation. Any given fund can only build a finite number of new companies at a given time. It’s only possible for one fund to do the scientific ideation and team building involved in their process for a very small number of companies each year. This number can actually go down as partners saturate the number of board seats and operating roles that they can reasonably hold. Simply put, this model doesn’t have the intrinsic network effects of the Silicon Valley tech ecosystem. The second crucial drawback is that scientists and engineers—the crucial value generators in high-tech innovation—aren’t in charge of their destiny. In tech, founders are in control of their cap table. YC companies are coached to only sell a small fraction of their company to investors early on. In biotech venture creation, VC funds take the lion’s share of equity from the start. It can be a bit like the difficult negotiation in Bad Santa, where Willie and Marcus end up giving half of their profits away to their new business partner Gin. But the numbers can actually be even more dramatic. We’re not talking about giving up half of the equity, we’re talking about a scenario where key founding scientists can receive single digit equity percentages, if they even receive any equity at all. In a world where their work can create billions of dollars of value, many biotechnologists are capturing miniscule fractions of these returns. The problem here isn’t just financial. Ownership has an important consequence: control over the direction of a company. A central component of venture creation is the process of building out a management team of executives who have experience bringing drugs to market. This means that scientists and engineers often don’t steer the trajectory of new companies. Leave it to the professionals! While this can be effective for executing within an existing paradigm, it doesn’t forge new ones. Google and Facebook weren’t built by former IBM executives, they were built by young programmers exploring totally different approaches to technology development and company culture. In the aftermath, we now have an existence proof for the fact that young engineers can build and lead massive generational companies. Things are starting to change. While biotech has traditionally been the realm of only specialist investors, tech VCs have made a serious entry. These investors have brought some of the dynamics of tech entrepreneurship with them. Since making their first biotech investment in Ginkgo Bioworks (read more about that story here), YC now funds more biotech startups each year than any other investor—giving scientists a totally different option compared to the venture creation route. The software powerhouse a16z has raised several massive biotech funds, and their partners have been vocal proponents of giving scientists the reins to their own companies. This trend is often referred to as the founder-led biotech movement. Founder-led companies are beginning to make a real mark on the industry. The investor Tony Kulesa framed this beautifully in a recent essay, saying:

This general shift in the biotech VC ecosystem isn’t limited to just a smaller subset of anomalous companies. As the blood bath in public markets has dropped the number of biotech IPOs, emerging techbio funds have actually overtaken more traditional biotech funds at the Series A stage: Beyond seed and series A investments, late-stage investors have also signaled a willingness to finance founder-led biotechs. Over time, this pipeline should only become more robust as some of the companies become massively successful. All of these changes have the potential to open the floodgates for a techbio revolution where company creation is accelerated, capital is more evenly distributed across more companies, and scientists are able to bring incredible new technologies out of their labs and into the market with less friction. Here, the key take home message is that one central component of techbio actually has nothing to do with AI, software, or robots: one of the major changes is the adoption of the tech investment and company creation model where founders are at the helm. To learn how techbio companies are deeply integrated, backed by new services, and potentially massive, with real examples…Thanks to Elliot for the excellent techbio overview and Dan for editing! Subscribe to Elliot’s newsletter, The Century of Biology, to stay up to date with the techbio revolution. That’s all for today, we’ll see you Friday morning for a Weekly Dose of Optimism! Thanks for reading, Packy If you liked this post from Not Boring by Packy McCormick, why not share it? |

Older messages

Weekly Dose of Optimism #8

Friday, August 19, 2022

Universal Vaccines, Cancer in the Cold, High-Skilled Immigration, The Immigration Flywheel, and the Europeans Come Back to Nuclear

The Space Economy

Monday, August 15, 2022

Payload Space joins us to drop an in-depth S-1 for space

Weekly Dose of Optimism #7

Friday, August 12, 2022

Moderna, Reddit Herpes, Carbon Capture, Serena, and Technological Stagnation?

Everything is Broken

Monday, August 8, 2022

Kevin Miao explains a very real crypto use case: fixing the $14T securitization market

Weekly Dose of Optimism #6

Friday, August 5, 2022

Mini Nuclear Reactors, CHIPs, 1000000x Engineers, Alzheimer's and Undead Pigs

You Might Also Like

🦸🏻#7: From Agentic AI to Physical AI

Saturday, January 11, 2025

How Jensen Huang worked backwards to start creating the future for the world + trends in AI and Robotics to keep an eye on

Voice search is the future

Saturday, January 11, 2025

Within the next 10 years, the majority of searches will be voice-driven. Voice search is changing the way people interact with search engines—and it's creating new opportunities for businesses to

Saturday Stuff: January 11th 2024

Saturday, January 11, 2025

January 11, 2025 | Read Online Saturday Stuff: January 11th 2024 Happy Saturday! Here's some stuff I'm checking out this weekend: #1 nader dabit @dabit3 New Video - Building an AI Agent with

Your Competition Isn’t Always Out to Get You

Saturday, January 11, 2025

It Often Just Doesn't Care To view this email as a web page, click here saastr daily newsletter This edition of the SaaStr Daily is sponsored in part by Stripe Your Much Bigger Competition Isn'

Does Google like my site now?

Saturday, January 11, 2025

If not, who cares. If they do...great!

'Do It, Even If You're Afraid'

Saturday, January 11, 2025

We spoke with sports anchor and reporter Tina Nguyen about adapting to change, building confidence as a public speaker, and fostering genuine connections in a world increasingly dominated by instant

A record-shattering credit year

Saturday, January 11, 2025

Also: 2024 VC data is here; Venture performance set to rebound in latest data; New research on AI and healthcare, legal tech, and warehouse robotics. Read online | Don't want to receive these

A 300% increase in sales??

Saturday, January 11, 2025

Seats are going fast! Don't miss out! View in browser ClickBank Logo -- BREAKING NEWS -- One-on-one coaching is now available in February! This is your chance to work directly with one of the best

Easy to understand tutorials via email

Saturday, January 11, 2025

I love that you're part of my network. Let's make 2025 epic!! I appreciate you :) Today's hack Easy to understand tutorials via email Text is boring. Create a short video tutorial, upload

Agency advice when you need it

Saturday, January 11, 2025

Hi there , Running an agency means needing different advice at different times. Sometimes you just need quick feedback from someone who gets it. Which is why I'm building a place for agency owner..