The Storyletter - Isenhart

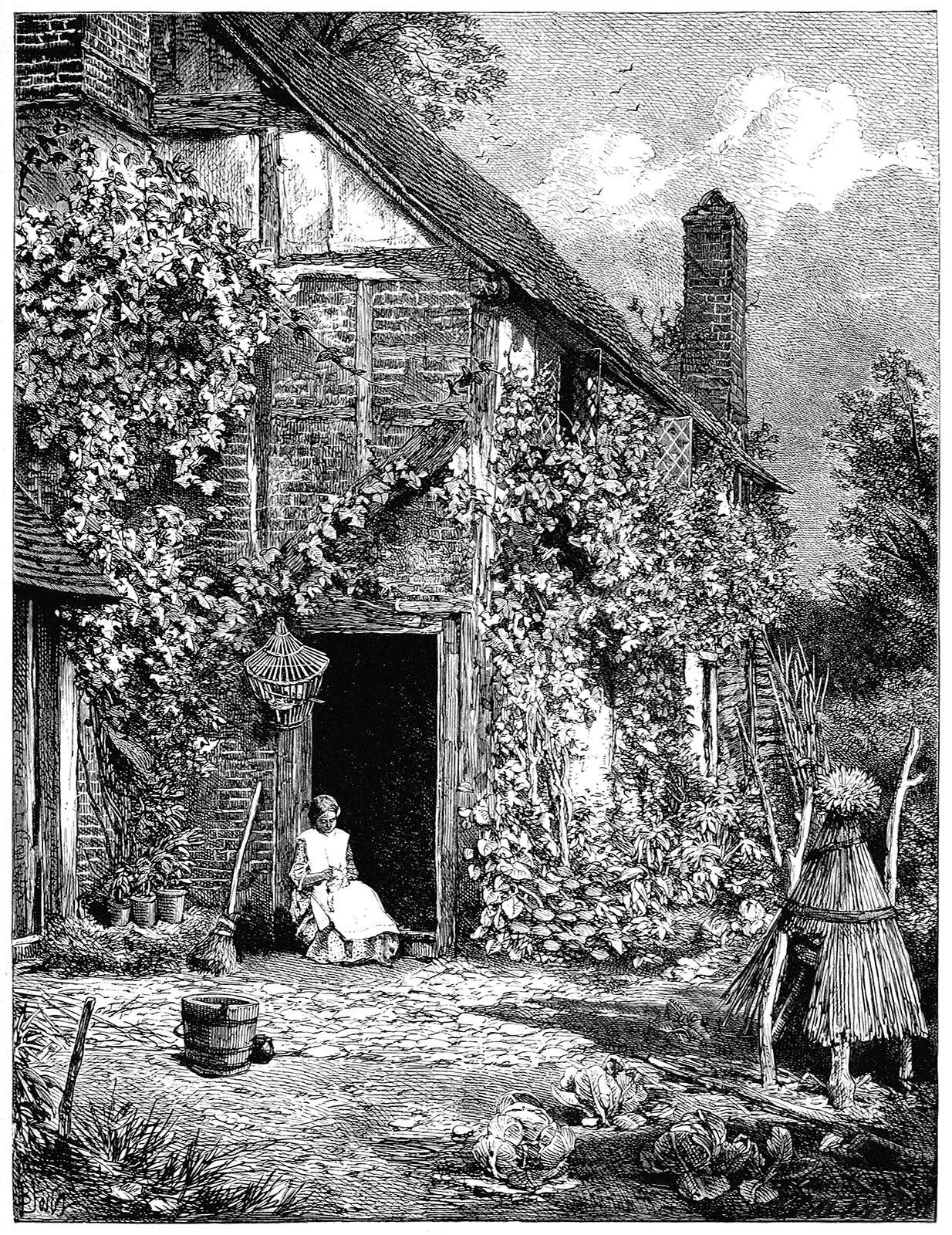

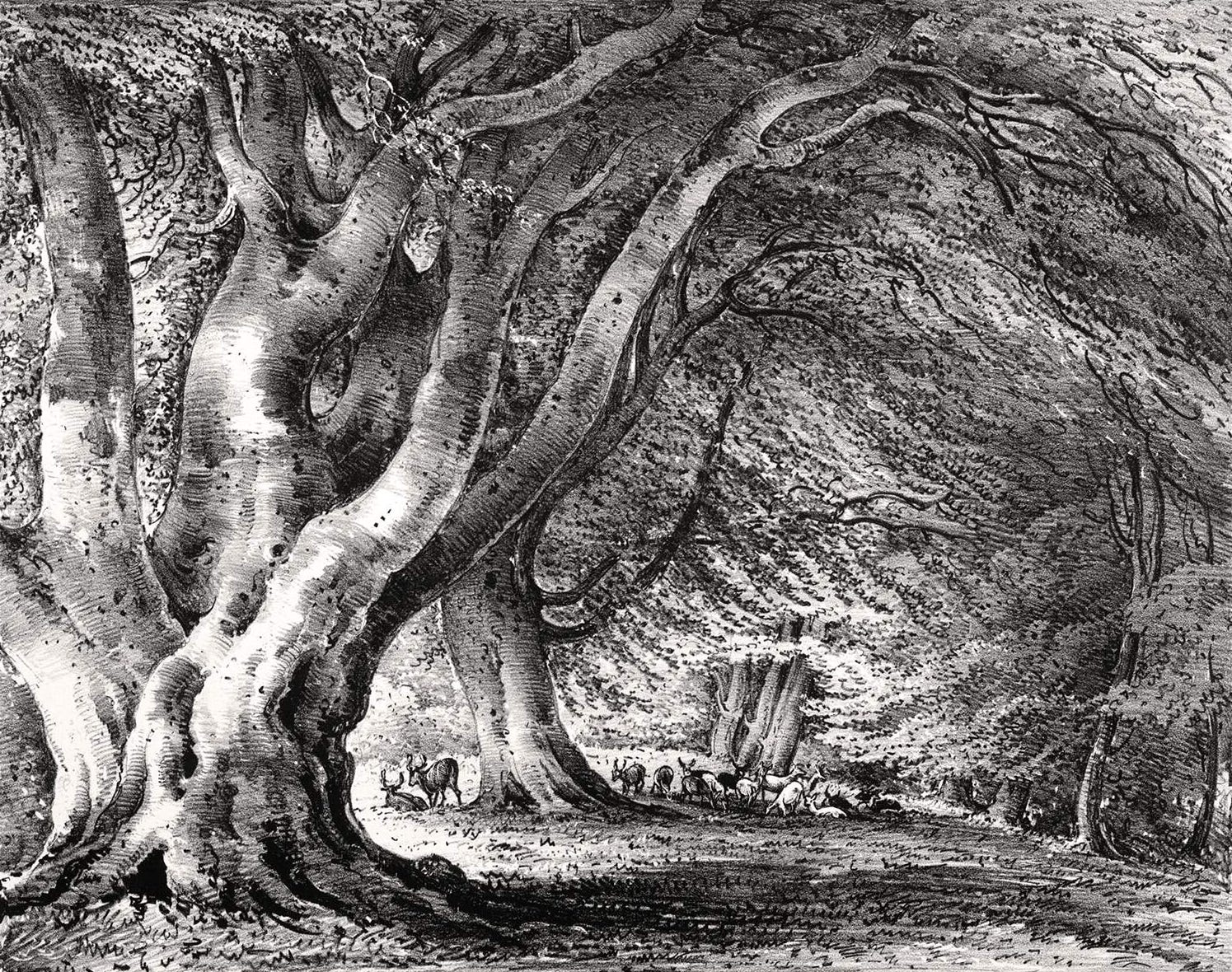

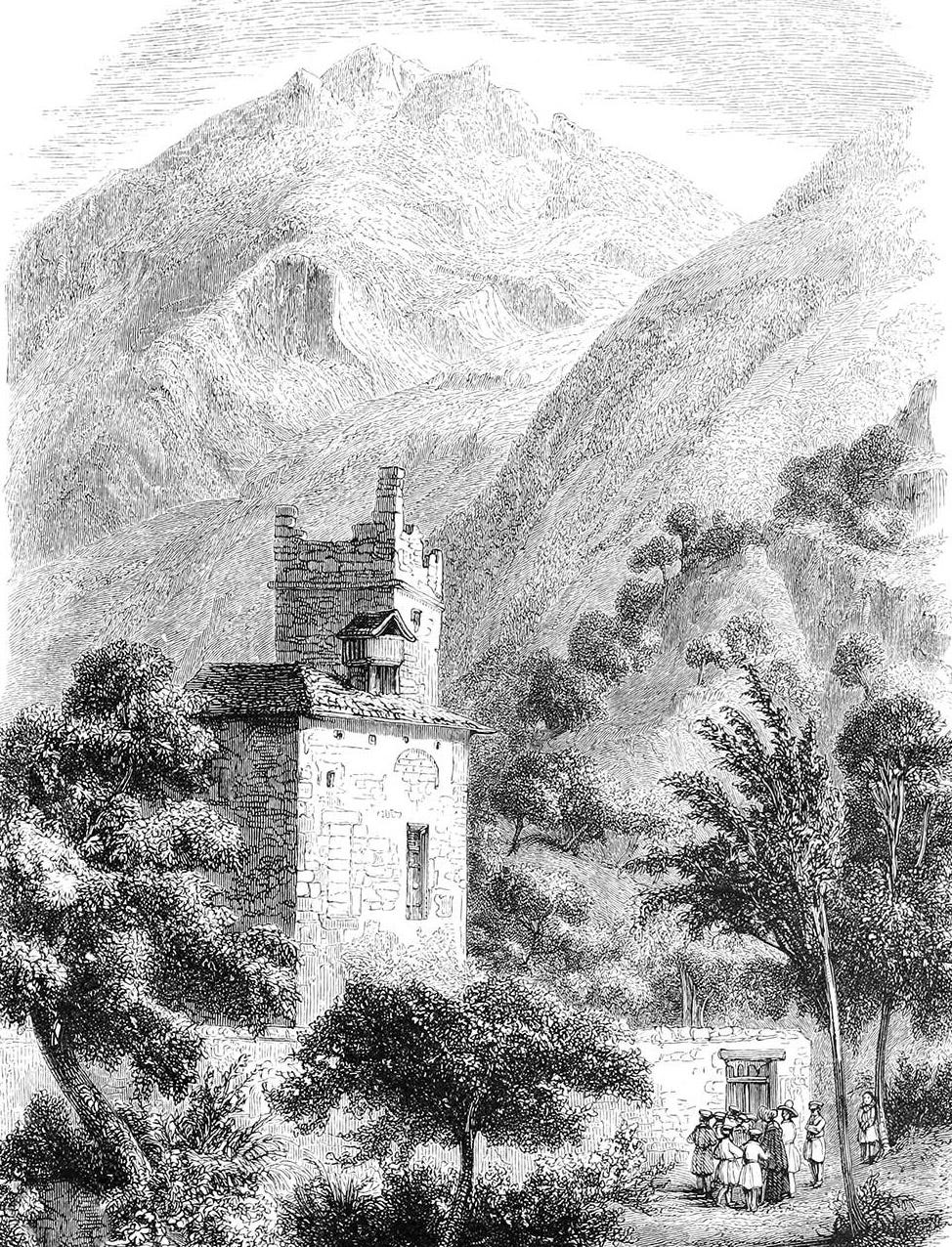

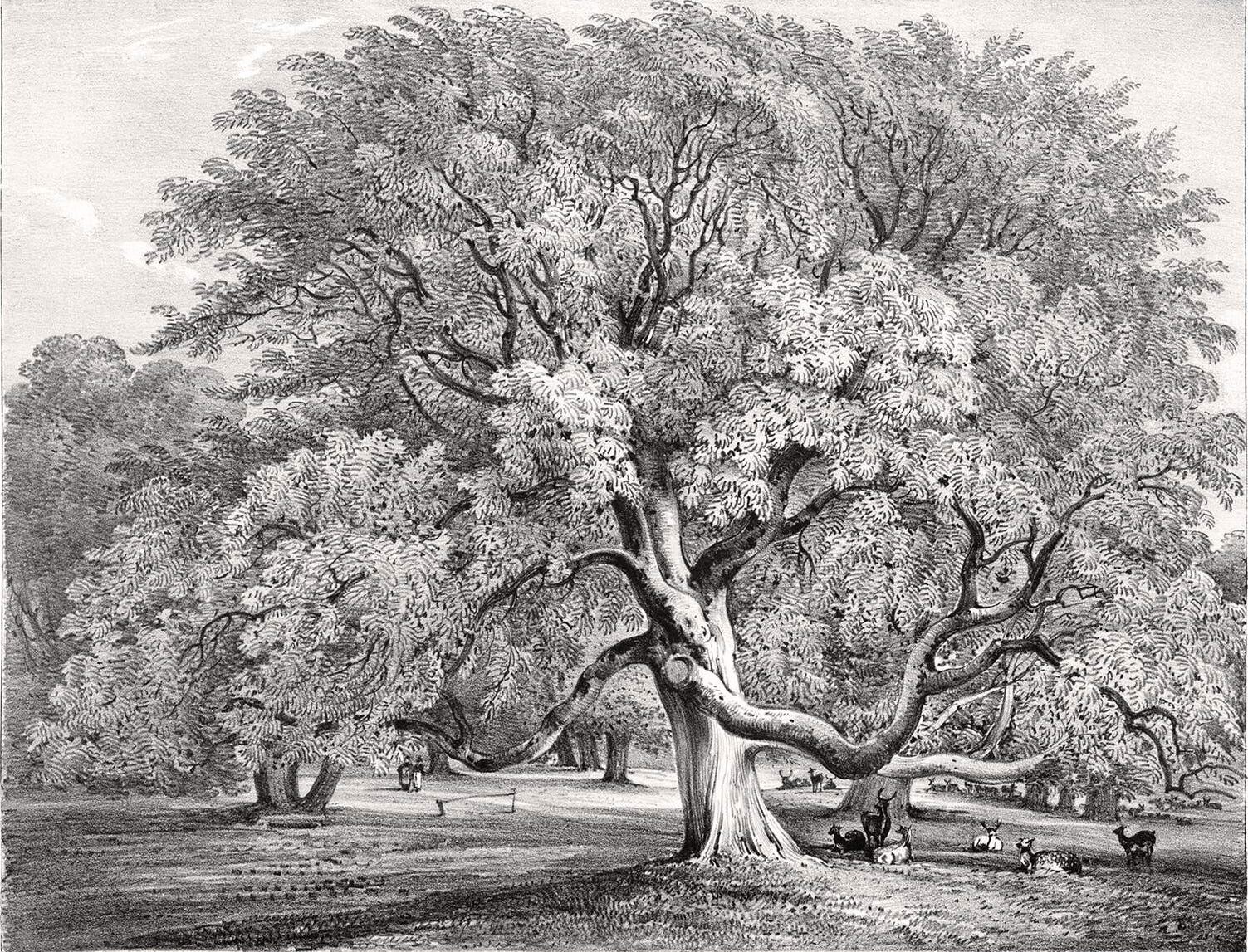

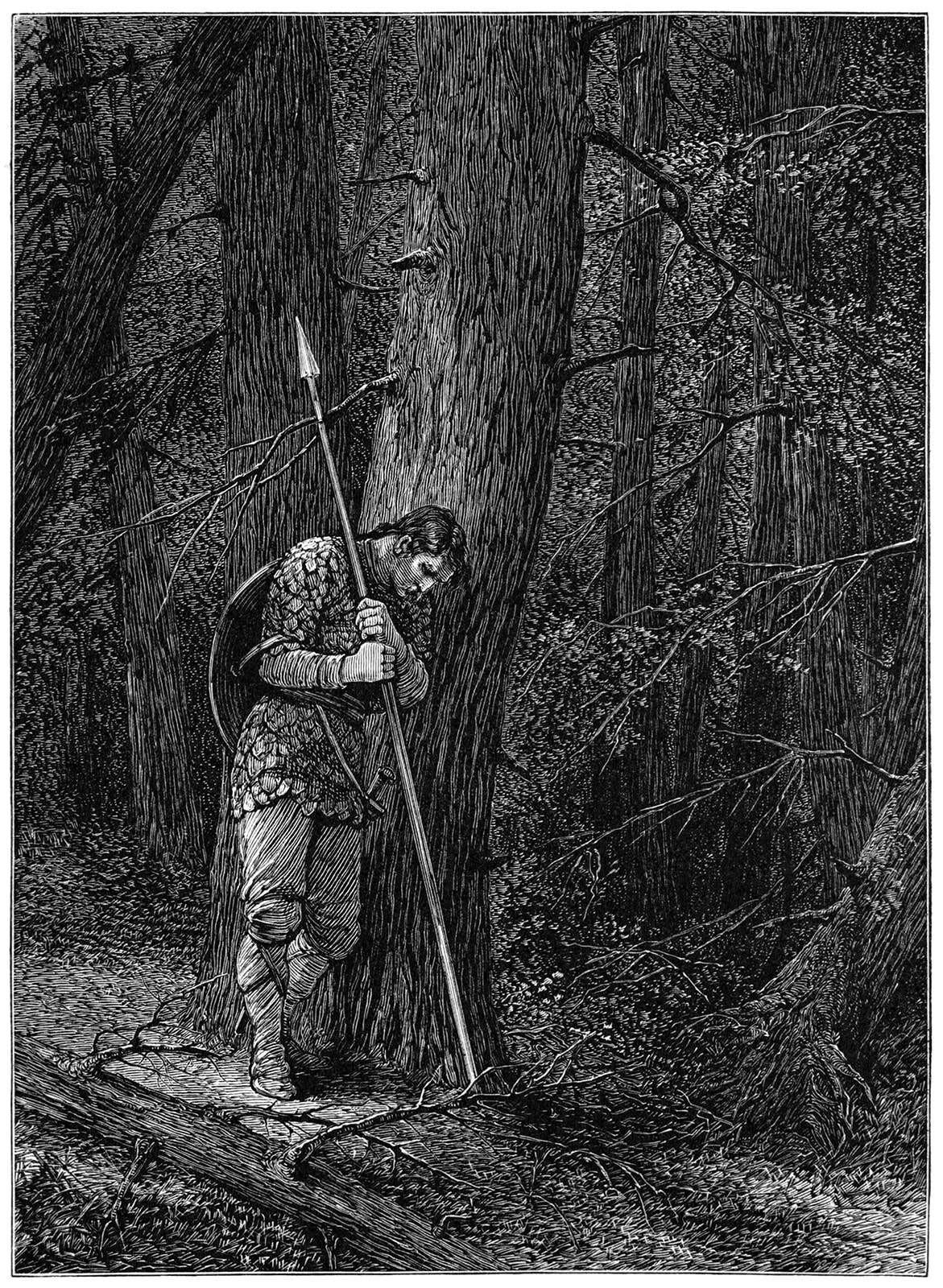

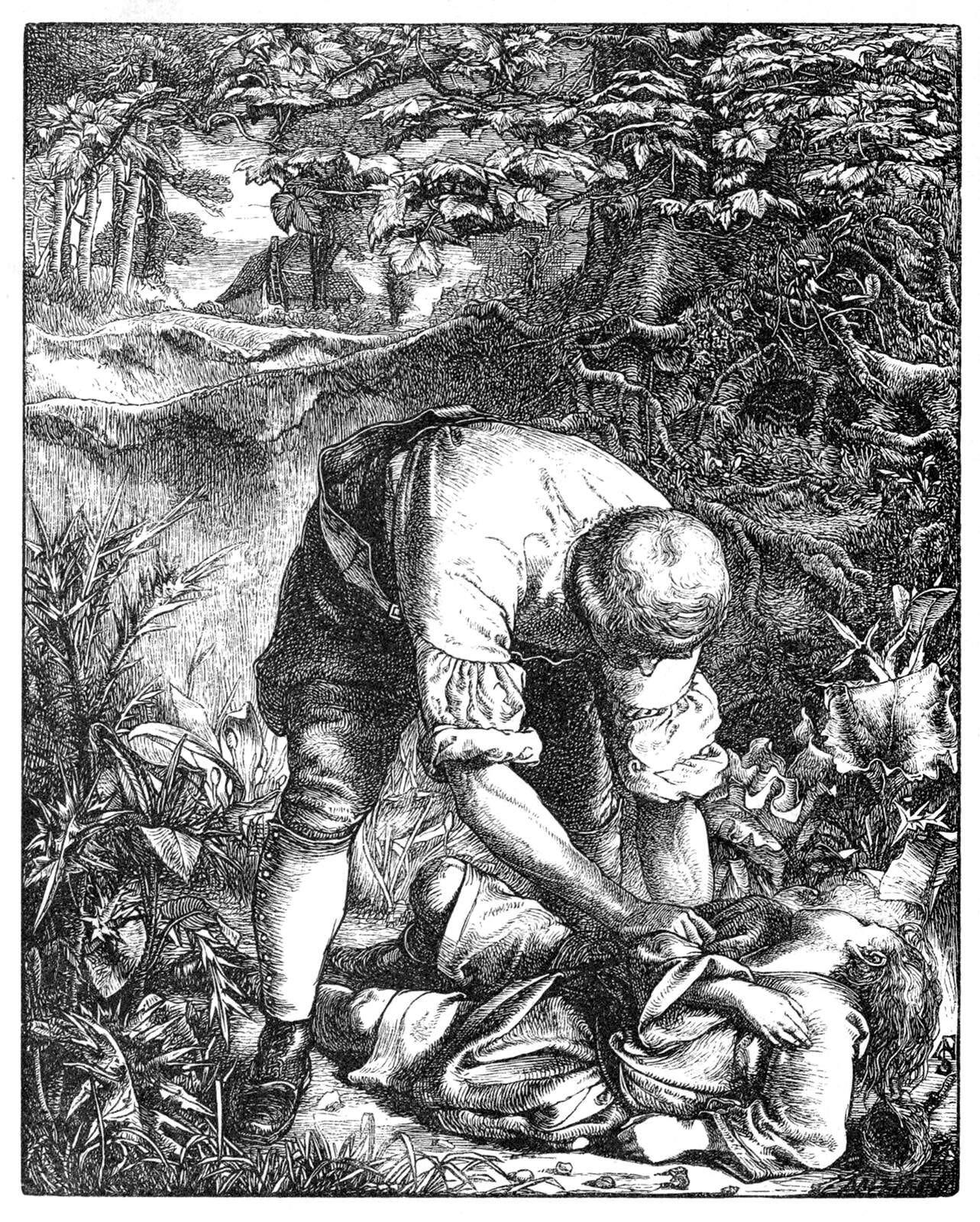

IsenhartGood intentions haunt an elderly peasant couple for years as they struggle to reckon with a good deed gone wrong.This short story was written in response to The Storyletter’s Flip a Common Trope writing prompt. Because I write historical fiction heavily influenced by ancient history and mythology, I chose a common trope from this realm. I wrote it this weekend while recovering from Covid, so it’s still a little rough around the edges. I don’t usually write short fiction, but I didn't want to miss out on an excuse to exercise those unused muscles. Hope you enjoy! Ansgar and Alruna stared at each other across the tiny table in their humble cottage. The small farmstead stood like an island in a dark sea of forest. The few hours of daylight permitted by the palisade of trees were already burning low. Soon the sun would slip behind the curtain of forest, and they would be at the night’s mercy—at his mercy. “We can’t go on like this,” Alruna said to Ansgar. “If you won’t do something about it, I will.” “Oh, you’ll do something, will you? Haven’t you done enough?” “What’s that supposed to mean?” “This whole mess is your doing.” “My doing?” She rocked back in her chair with her brows raised. “How do you figure that?” “You never had so much as a smile for him. Never gave an ounce of love.” Ansgar folded his arms over his chest and let his eyes bore into her. “Is it any wonder it’s come to this?” “I never asked for this, did I? We were doing just fine on our own. But you couldn’t leave well enough alone. Did you ever stop to think maybe those women knew something you didn’t? Maybe they had a good reason? Of course not. Ansgar always knows best!” “Do you ever shut up, woman?” “Ansgar is the big hero who will save the world! Ansgar needs everyone to love him! You should have let the wolves— Alruna broke off as they both startled at the sound of creaking wood behind the cottage. They turned and strained to listen. “It’s nothing,” said Ansgar, his voice trembling. “The roof settling.” “Then you can go look,” Alruna said and reached for the knife beside the loaf of bread on the cutting board. Ansgar heaved himself to his feet and glanced sullenly at Alruna, then toward the door at the back of the cottage that led to the attached barn where their few remaining livestock bedded down at night. He took a step toward the door, paused, then doubled back to grab his axe from its peg above the woodpile beside the hearth. Turning this over in his hand, he fixed his grip and, with a heavy head, approached the door. Pulling it open, he was greeted by the milk cow he’d brought out to the pasture that morning—or, rather, her head, laid before him in the straw. Isenhart had returned. As soon as the boy was old enough, Ansgar had begun taking him into the forest when he’d set his traps and sometimes hunt to teach him the necessities of providing for the table. Most boys took to hunting and bushcraft with enthusiasm, but Isenhart was different. Even Ansgar had to admit that though he loved the boy as if he were his own flesh and blood, he was an odd one. For one thing, he never spoke. Not a single word. Though he was quick to learn and understood when spoken to, he simply refused to talk to Ansgar and Alruna. Then there were the animals. The first time they had come across a live rabbit caught in one of the snares, Ansgar showed the boy how to dispatch the creature quickly and painlessly. But when it came time for Isenhart to do the same, he lingered over the task, pretending to fumble as the poor creature shrieked in terror and pain. Ansgar shrugged it off as a novice mistake or a boy’s dark curiosity. After all, what lad hadn’t pulled the wings from a bug or two in his day? But it wouldn’t be the last time. He seemed to often miss his shots with the bow, and Ansgar would find him sitting over the beasts, watching them expire slowly. He deliberately dissected rather than butchered slaughtered livestock, and they once found a sow’s heart stashed beneath his pillow as it began to fester. Isenhart seemed entranced by fear and death in a way that chilled the old hunter in his bones. Eventually, Ansgar marched him out to the barn and took his belt to him whenever the boy went too far. When that didn’t work, he tried the rod. When Isenhart flayed a live lamb, Ansgar held his head in the trough until he nearly drowned. But nothing seemed to phase him. If anything, it made him fiercer. Alruna hadn’t slept soundly in ages with the boy under her roof, and she had more work than ever foraging and replanting the garden now that most of the livestock was gone. Her tired old joints had suffered long enough. He was more than they could handle. She demanded that Ansgar bring him through the woods to the castle, where they could give him a position in service and discipline him properly. Finally, reluctantly, Ansgar agreed. But, that night, Isenhart disappeared into the forest. It wasn’t the first time. He would often abscond into the wood. When old enough to run, he’d steal away into the forest for days and not return. The first time they were terrified and searched for him day and night. After he’d done it a few times, they stopped looking. Ansgar had said the forest spirit was part of him after his troubled beginning. It was only natural he’d feel at home there. Alruna thought differently. She said the boy was a feral beast unfit for human society. It angered Ansgar when she spoke like that—she didn’t see the boy like he did. There was something special about him, about the way he discovered him. Ansgar was meant to find him—to save him. He was sure of it. But now they worried, not about what might happen to him in the forest, but about what he was up to out there. The tales had begun to reach them. Travelers, they said, often failed to arrive at their destination when passing through the wood. Traders no longer came by the farmstead because of the danger lurking there. And their friends from neighboring farms ceased their visits. Soon, the couple saw no one. Alruna worried about Ansgar entering the wood to hunt or forage, though Ansgar was certain the danger was not to him. He’d been good to the boy, hadn’t he? It was Alruna who never quite got on with Isenhart. Ansgar thought she would be elated to have a child to raise. Didn’t all women love children? Wasn’t motherhood their natural calling? But from the moment the child entered their lives, she seemed perturbed by his presence. And as the child grew, she resented him even more. True, the boy was a handful, but the joyful woman Ansgar adored had disappeared when he brought the child home to live with them, and a bitter, indignant stranger had taken her place. Alruna knew how much Ansgar wanted children, so she never told him about the herbs. They already struggled to feed and clothe themselves on the small farm most years without the burden of more mouths to feed. It would have hurt Ansgar’s pride to say their poverty kept them childless, so Alruna pretended to be barren and took the shame on herself. Still, they’d always enjoyed a peaceful and contented life together. Or, they once had. She tried to love the boy for Ansgar’s sake, but her heart simply refused. Something deep inside her revolted at the sight of him. She finally understood why mother birds shoved some chicks from their nests. With the chickens, sheep, pigs, and now their beloved milk cow gone, it was time to face the harsh reality that they’d never last the winter on the farm. She’d put up some roots from the garden, but there was hardly enough to keep them through the long, cold season. They tried to think what could be done. Alruna began to form a plan, but she knew Ansgar would never agree if he knew the whole of it. So, she convinced him that their only hope was to fall on the mercy of the king in the castle. Shameful as it was, they would have to go begging if they would survive the winter. Alruna stood before the massive oaken gates strapped and studded with iron, wondering if the king would even believe the terrible story she planned to tell. The peasants had never been to the castle, as the tax collectors came to them. She shook with angst now as they awaited an audience. But even from his high, safe perch, the king must have heard word of the terrible menace lurking in the forest. He must know that traders and travelers feared to pass there now. He would never suspect the elderly farmers were the cause. Would he punish them or help them free the forest of this curse? King Sigward was a young, soft-spoken man with a gentle aspect which surprised and put them at ease. In hopes of winning his sympathy and a bit of charity, Ansgar began to explain how they had lost all their stock to an unfortunate series of accidents. But Alruna boldly interrupted with the truth: it was no accident. There was a monster on the loose—one of their making. The king, sitting upon his gilded chair, leaned forward, bemused and intrigued, demanding to know how this could be. Ansgar had left his farmstead beside the creek and trekked into the forest to check his snares and traps. As he crouched in the underbrush, retrieving a hare and resetting a snare, he heard voices in the distance. He hid himself, as the woods were full of bandits. But then he realized the voices were those of two women, and he remained out of sight because he didn’t want to be mistaken for a robber or rapist. So he simply waited for them to pass by. But as he watched, he witnessed something he never expected. One of the women carried a child in her arms, and as she passed under the great ash tree at the center of the grove, she stepped from the path and laid the writhing baby among its gnarled roots. Then both women spat upon it, gathered up their cloaks around them, and hurried back along the path the way they’d come. No tears were shed, they never looked back, and not a word was spoken. Ansgar was horrified. Mystified. How could anyone, let alone two women, treat an infant this way? After an hour or so, when he was sure the women would not return, and no one else had come along, Ansgar approached the tree where the child had been left. In the shade of the forest’s dense spring canopy, the baby slept peacefully, seemingly unaware of the cruelty it had suffered. Ansgar carefully pulled back the blanket that swaddled the infant. He peeked under the diaper cloth. There were no signs of disease or deformity to be seen, and he could not fathom why anyone would abandon a perfectly healthy child—especially a boy—in the forest. He had longed all his life for a son and he wasn’t getting any younger. He could use a hand around the farm and when out hunting. And, of course, he thought of his poor wife. He knew it broke her heart all these years that they had never been blessed with a child of their own. And, though he tried to assure her that he harbored no resentment, she had to feel like less of a woman because she could not give him an heir. Looking at this little lost babe, he knew what he had to do. King Sigward put his face in his hands and began to weep as Ansgar and Alruna looked on in bewilderment and slight embarrassment. They didn’t know whether they should speak or perhaps leave the chamber. But then the king wiped his face and began to speak. “My queen died in childbirth,” he said. “I also have no heir. The child, a boy, died, too.” “Condolences, your majesty,” Ansgar replied, not knowing what else to say but moved to pity by the pain the man clearly felt. “Well, that was the tale I told the world. I should have drowned the fiend in a bathtub. Alas, I am a man of God. Or, that is what I tell myself.” He rested his head in his hands while Ansgar and Alruna exchanged confused, worried glances. “My poor wife swore it felt like the child was trying to claw its way out—trying to kill her. The physicians scoffed at her womanly weakness. When she finally succumbed, the surgeons cut her open to save the infant prince. They said it was like a wild animal had been trapped inside—they’d never seen the like. The creature even refused to suckle from the wetnurses, but drew blood instead.” Alruna turned to whisper to Ansgar: “I knew there was something off about that child the moment I laid eyes on it.” “Are you never tired of being right?” Ansgar snapped. “You understand now why we did what we did?” asked Sigward apologetically. “I only regret that I lacked the mettle to finish it with my own hand. And that those nurses didn’t travel further from the path.” “You have the chance to finish it now, my king,” Alruna said. “Unleash your knights and hounds in the forest and show the creature no more mercy than you would a bear or wild boar—for he is just as savage.” Ansgar was a fine hunter, but his stamina was not what it once was. Having taught everything he knew to Isenhart, he worried he’d be no match for the young boy’s boundless energy. Still, he and Alruna joined the hunt, Ansgar with his spear in hand and Alruna carrying Ansgar’s bow. There would be nowhere for Isenhart to hide with the king’s knights and his huntsman’s hounds on the scent. The forest was deep, dense, and dark. There were many places for a creature to go to ground. But a boy could not outrun hounds and horses for long. Soon, the king’s men cornered him in a stony hollow under an autumn canopy of ash and elm. They found him bathing his face in the blood of a fawn. He preferred raw flesh to that cooked over a fire. As Sigward and his men gathered around to finish the business they’d come for, the boy grew still and let his eyes fall on Ansgar with a pitiful, pleading look. The old farmer lowered his spear. Then Sigward lowered his spear, and the rest of the knights followed. “Oh, my son,” Sigward said, overcome with emotion, “look how you have grown.” He bent to lay his spear on the ground. Suddenly, Isenhart shrieked, hissed, then fell writhing in the dirt. When Sigward and the knights looked up, they saw he’d been pierced through the chest with an arrow. “No!” Sigward cried and fell to his knees. Ansgar rushed to the dead boy’s side. “Woman, what have you done!” “What none of you could,” said Alruna. Then she turned and headed for home where, after many years, she would once again sleep in peace. The trope I chose to subvert was one in which a hero, usually of royal birth, is cast out into the wilderness as an infant and left to die, but is taken in by common folk who raise him (or rarely her) with respectable values until he’s ready to claim his birthright. Spare heirs were often hidden in inconspicuous places because of their high murder rate (like early witness protection), so it’s a compelling trope that probably has some basis in reality. I thought it would be fun to ask the question: what if the exile wasn’t destined to be a hero, and they had a good reason for casting the kid out in the cold? Examples from myth and literature:

Do you have any other examples?

|

Older messages

Interview with Jackie Dana

Friday, February 17, 2023

Jackie discusses YA fantasy, St. Louis history, and publishing a book series

The Way Forward

Saturday, February 11, 2023

The Storyletter cross-posted a post from Lamp Post in the Marsh Winston MaloneFeb 11 · The Storyletter Dear Reader, This week I'm sharing a poem by Daniel W. Davison called "The Way Forward

Self-Publishing on Amazon KDP

Wednesday, February 8, 2023

A helpful introduction to Kindle Direct Publishing

A Crooked Cane Comes a Knockin' (announcement)

Saturday, February 4, 2023

Preview | Supernatural Horror

To Build a Brand | A look into Donald Miller's Storybrand Framework

Wednesday, February 1, 2023

XPress Access | January/February 2023 Edition

You Might Also Like

*This* Is How To Wear Skinny Jeans Like A Fashion Girl In 2025

Wednesday, March 12, 2025

The revival is here. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 3.11.2025 This Is How To Wear Skinny Jeans Like A Fashion Girl In 2025 (Style) This Is How To Wear Skinny Jeans Like A Fashion Girl In 2025 The

The Best Thing: March 11, 2025

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

The Best Thing is our weekly discussion thread where we share the one thing that we read, listened to, watched, did, or otherwise enjoyed recent… ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Most Groundbreaking Beauty Products Of 2025 Are...

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Brands are prioritizing innovation more than ever. The Zoe Report Beauty The Zoe Report 3.11.2025 (Beauty) The 2025 TZR Beauty Groundbreakers Awards (Your New Holy Grail Or Two) The 2025 TZR Beauty

Change Up #Legday With One of These Squat Variations

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE Change Up #Legday With One of These Squat Variations Change Up #Legday With One of These Squat Variations The lower body staple is one of

Kylie Jenner Wore The Spiciest Plunging Crop Top While Kissing Timothée Chalamet

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Plus, Amanda Seyfried opens up about her busy year, your daily horoscope, and more. Mar. 11, 2025 Bustle Daily Amanda Seyfried at the Tory Burch Fall RTW 2025 fashion show as part of New York Fashion

Paris Fashion Week Is Getting Interesting Again

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Today in style, self, culture, and power. The Cut March 11, 2025 PARIS FASHION WEEK Fashion Is Getting Interesting Again Designs at Paris Fashion Week once again reflect the times with new aesthetics,

Your dinner table deserves to be lazier

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

NY delis are serving 'Bird Flu Bailout' sandwiches.

Sophie Thatcher Lets In The Light

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Plus: Chet Hanks reaches new heights on Netflix's 'Running Point.' • Mar. 11, 2025 Up Next Your complete guide to industry-shaping entertainment news, exclusive interviews with A-list

Mastering Circumstance

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

“If a man does not master his circumstances then he is bound to be mastered by them.” ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Don't Fall for This Parking Fee Scam Text 🚨

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

How I Use the 'One in, One Out' Method for My Finances. You're not facing any fines. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY Don't Fall for the