The Generalist - The History of AI in 7 Experiments

The History of AI in 7 ExperimentsThe breakthroughs, surprises, and failures that brought us to today.📬 A small note: If this email landed in your “Promotions” tab, please take a moment to drag it over into “Primary.” This helps ensure The Generalist arrives to you on time and doesn’t get lost in the email dungeon. Friends, In their classic work, The Lessons of History, husband and wife Will and Ariel Durant analyzed the story of human civilization. Among their pithy and profound observations is this meditation: “The present is the past rolled up for action, and the past is the present unrolled for understanding.” No aspect of our present moment feels more ready to act upon the fabric of our lives quite as radically as artificial intelligence. The technology is accelerating at a pace that is hard to comprehend. A year ago, crowd-sourced predictions estimated artificial general intelligence would arrive in 2045; today, it’s pegged at 2031. In less than a decade, we could find ourselves competing and collaborating with an intelligence superior to us in practically every way. Though some in the industry perceive it as scaremongering, it is little wonder that a swathe of academia has called for an industry-wide “pause” in developing the most powerful AI models. To understand how we have reached this juncture and where AI may take us in the coming years, we need to unroll our present and look at the past. In today’s piece, we’ll seek to understand the history of AI through seven experiments. In doing so, we’ll discuss the innovations and failures, false starts and breakthroughs that have defined this wild effort to create discarnate intelligence. Before we begin, a few caveats are worth mentioning. First, we use the term “experiments” loosely. For our purposes, an academic paper, novel program, or whirling robot fit this definition. Second, this history assumes little to no prior knowledge of AI. As a result, technical explanations are sketched, not finely wrought; there are no equations here. Thirdly, and most importantly, this is a limited chronicle, by design. All history is a distillation, and this piece is especially so. Great moments of genius and ambition exist beyond our choices. One final note: This piece is the first installment in a mini-series on the foundations and state of modern AI that we’ll add to in the weeks and months to come. We plan to cover the field’s origins and technologies, and explore its most powerful companies and executives. If there are others you think would enjoy this journey, please share this piece with them. A quick ask: If you like this piece, I’d be grateful if you’d consider tapping the ❤️ at the top of this email. It helps us understand which pieces are resonating and which topics we should keep exploring! Brought to you by VantaGrowing a business? Need a SOC 2 ASAP? Vanta, the leader in automated compliance, is running a one-of-a-kind program for select companies where we'll work closely with you to get your SOC 2 Type I in JUST TWO WEEKS. Companies that qualify to participate will get a SOC 2 Type I report that will last for a year. This can help you close more deals, hit your revenue targets, and start laying a foundation of security best practices. Due to the white glove support offered in this pilot, spots are limited. Complete the form to learn more and see if you qualify. The History of AI in 7 ExperimentsActionable insightsIf you only have a few minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders should know about AI’s history.

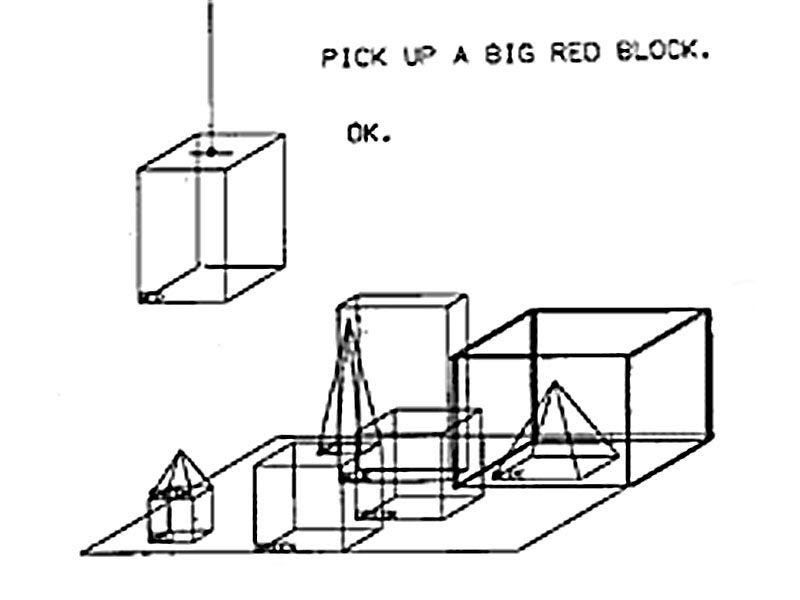

Experiment 1: Logic Theorist (1955)A mile from the Connecticut River’s banks, congregational minister Eleazar Wheelock founded Dartmouth in 1769. It is an august if modestly-sized university located in the town of Hanover, New Hampshire. “It is, Sir, as I have said, a small college, and yet there are those who love it,” famed 19th orator and senator Daniel Webster is supposed to have said of his alma mater. Nearly two hundred years after the center of learning settled on a piece of uneven land optimistically named “the Plain,” it hosted a selection of academics engaged in a task Wheelock might have found sacrilegious. (Who dares compete with the divine to create such complex machines?) In 1956, John McCarthy – then assistant professor of mathematics – convened a 12-week workshop on “artificial intelligence.” Its goal was nothing less than divining how to create intelligent machines. McCarthy’s expectations were high: “An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans,” he had written in his grant application. “We think that a significant advance can be made in one or more of these problems if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it together for a summer.” That exclusive group included luminaries like Claude Shannon, Marvin Minsky, Nat Rochester, and Ray Solomonoff. For a field so often defined by its disagreements and divergences, it is fitting that even the name of the conference attracted controversy. In the years before McCarthy’s session, academics had used a slew of terminology to describe the emerging field, including “cybernetics,” “automata,” and “thinking machines.” McCarthy selected his name for its neutrality; it has stuck ever since. While the summer might not have lived up to McCarthy’s lofty expectations, it contributed more than nomenclature to the field. Allen Newell and Herbert Simon, employees of the think-tank RAND, unveiled an innovation that attained legendary status in the years that followed. Funnily enough, attendees largely ignored it at the time – both because of Newell and Simon’s purported arrogance and their tendency to focus on the psychological ramifications their innovation suggested, rather than its technological importance. Just a few months earlier, in the winter of 1955, Newell and Simon – along with RAND colleague Cliff Shaw – devised a program capable of proving complex mathematical theorems. “Logic Theorist” was designed to work as many believed the human mind did: following rules and deductive logic. In that respect, Logic Theorist represented the first example of AI’s “symbolic” school, defined by this adherence to structured rationality. Logic Theorist operated by exploring a “search tree” – essentially a branching framework of possible outcomes, using heuristics to hone in on the most promising routes. This methodology successfully proved 38 of the 52 theorems outlined in a chapter of Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica. When Logic Theorist’s inventors shared the capabilities of their program with Russell, particularly noting how it had improved upon one of his theorems, he is said to have “responded with delight.” Though overlooked that summer in Hanover, Logic Theorist has become accepted as the first functional artificial intelligence program and the pioneering example of symbolic AI. This school of thought would dominate the field for the next thirty years. Experiment 2: SHRDLU and Blocks World (1968)In 2008, CNNMoney asked a selection of global leaders, from Michael Bloomberg to General Petraeus, for the best advice they’d ever received. Larry Page, then President of Google, referred to his Ph.D. program at Stanford. He’d shown the professor advising him “about ten” different topics he was interested in studying, among them the idea of exploring the web’s link structure. The professor purportedly pointed to that topic and said, “Well, that one seems like a really good idea.” That praise would prove a remarkable euphemism; Page’s research would lay the groundwork for Google’s search empire. The advisor in question was Terry Winograd, a Stanford professor, and AI pioneer. Long before Winograd nudged Page in the direction of a trillion-dollar idea, he created a revolutionary program dubbed “SHRDLU.” Though it looks like the name of a small Welsh town typed with a broken Caps Lock key, SHRDLU was a winking reference to the order of keys on a Linotype machine – the nonsense phrase ETAOIN SHRDLU often appeared in newspapers in error. Winograd’s program showcased a simulation called “Blocks World”: a closed environment populated with differently colored boxes, blocks, and pyramids. Through natural language queries, users could have the program manipulate the environment, moving various objects to comply with specific instructions. For example, a user could tell SHRDLU to “find a block which is taller than the one you are holding,” or ask whether a “pyramid can be supported by a block.” As user dialogues show, SHRDLU understood certain environmental truths: knowing, for example, that two pyramids could not be stacked on top of each other. The program also remembered its previous moves and could learn to refer to certain configurations by particular names. Critics pointed to SHRDLU’s lack of real-world utility and obvious constraints, given its reliance on a simulated environment. Ultimately, however, SHRDLU proved a critical part of AI’s development. Though still an example of a symbolic approach – the intelligence displayed came about through formalized, logical reasoning rather than emergent behavior – Winograd’s creation showcased impressive new capabilities, with its natural language capabilities particularly notable. The conversational interface SHRDLU used remains ubiquitous today. Experiment 3: Cyc (1984)Jorge Luis Borges’s short story, “On Exactitude in Science,” tells the tale of a civilization that makes a map the size of the territory it governs. “[T]he Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it,” the Argentine literary master writes in his one-paragraph tale. Cyc is artificial intelligence’s version of the “point for point” map, a project so wildly ambitious it approaches the creation of an entirely novel reality. It has been lauded for its novelty and condemned as “the most notorious failure in AI.” In 1984, Stanford professor Douglas Lenat set out to solve a persistent problem he saw in the AI programs up to that point: their lack of common sense. The previous decade had been dominated by “expert systems”: programs that relied on human knowledge, inputted via discrete rules, and applied to a narrow scope. For example, in 1972, Stanford started work on a program named MYCIN. By drawing on more than 500 rules, MYCIN could effectively diagnose and treat blood infections, showing “for the first time that AI systems could outperform human experts in important problems.” While MYCIN and its successors were practical and often impressive, Lenat found them to be little more than the “veneer” of intellect. Sure, these programs knew much about blood disease or legal issues, but what did they understand beyond prescribed confines? To surpass superficial intelligence, Lenat believed that AI systems needed context. And so, in 1984, with federal support and funding, he set about building Cyc. His plan was deceptively simple and utterly insane: to provide his program with necessary knowledge, Lenat and a team of researchers inputted rules and assertions reflecting consensus reality. That included information across the span of human knowledge from physics to politics, biology to economics. Dictums like “all trees are plants” and “a bat has wings” had to be painstakingly added to Cyc’s knowledge architecture. As of 2016, more than 15 million rules had been inputted. In Borges’s story, successive generations realize the uselessness of a map the size of the territory. It is discarded in the desert, growing faded and wind-tattered. Nearly forty years after Lenat set to work on the project, Cyc has yet to justify the hundreds of millions of investment and cumulative thousands of years of human effort it has absorbed. Though Cyc’s technology does seem to have been used by real-world stakeholders, experiments over the years have shown its knowledge is patchy, undermining its utility. In the meantime, newer architectures and approaches have delivered better results than Lenat’s more gradual approach. Ultimately, Cyc’s greatest contribution to the development of AI was its failure. Despite Lenat’s brilliance and boldness, and the commitment of public and private sector stakeholders, it has failed to break out. In doing so, it revealed the limitations of “expert systems” and knowledge-based AI. PuzzlerJust respond to this email if you’d like a hint.

Well played to Greg K, Saagar B, Bruce G, Michael O, Krishna N, Michael T, Kelly O, Varun K, Joshua K, SM, Upendra S, Kyle O, Xavier L, Nathan M, and Nnamdi E. All figured out this conundrum:

The answer? An echo. Well played to all. Until next time, Mario |

Older messages

Exploring Productive Bubbles

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

Not all speculation is created equal. How will we remember the AI, venture, crypto, and climate bubbles of the early 21st century?

Modern Meditations: Reid Hoffman

Sunday, April 2, 2023

The LinkedIn co-founder and Greylock partner discusses AI imagery, new nation-states, friendship, and “the storm before the calm.”

Mercury is Ready for the Moment

Wednesday, March 29, 2023

The unicorn banking platform built on a network of partner institutions is profitable, growing rapidly – and ready to become SV's new standard.

What to Watch in AI

Sunday, March 26, 2023

Ten companies AI founders and investors are keeping a close eye on.

The Wisdom List: Alex Bouaziz, CEO of Deel

Sunday, March 19, 2023

Deel's co-founder on speed, execution, and scaling a $12 billion business.

You Might Also Like

🚀 Ready to scale? Apply now for the TinySeed SaaS Accelerator

Friday, February 14, 2025

What could $120K+ in funding do for your business?

📂 How to find a technical cofounder

Friday, February 14, 2025

If you're a marketer looking to become a founder, this newsletter is for you. Starting a startup alone is hard. Very hard. Even as someone who learned to code, I still believe that the

AI Impact Curves

Friday, February 14, 2025

Tomasz Tunguz Venture Capitalist If you were forwarded this newsletter, and you'd like to receive it in the future, subscribe here. AI Impact Curves What is the impact of AI across different

15 Silicon Valley Startups Raised $302 Million - Week of February 10, 2025

Friday, February 14, 2025

💕 AI's Power Couple 💰 How Stablecoins Could Drive the Dollar 🚚 USPS Halts China Inbound Packages for 12 Hours 💲 No One Knows How to Price AI Tools 💰 Blackrock & G42 on Financing AI

The Rewrite and Hybrid Favoritism 🤫

Friday, February 14, 2025

Dogs, Yay. Humans, Nay͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

🦄 AI product creation marketplace

Friday, February 14, 2025

Arcade is an AI-powered platform and marketplace that lets you design and create custom products, like jewelry.

Crazy week

Friday, February 14, 2025

Crazy week. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

join me: 6 trends shaping the AI landscape in 2025

Friday, February 14, 2025

this is tomorrow Hi there, Isabelle here, Senior Editor & Analyst at CB Insights. Tomorrow, I'll be breaking down the biggest shifts in AI – from the M&A surge to the deals fueling the

Six Startups to Watch

Friday, February 14, 2025

AI wrappers, DNA sequencing, fintech super-apps, and more. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

How Will AI-Native Games Work? Well, Now We Know.

Friday, February 14, 2025

A Deep Dive Into Simcluster ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏