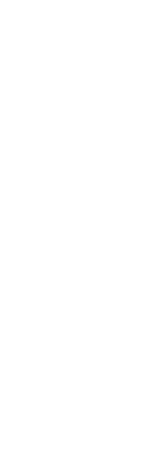

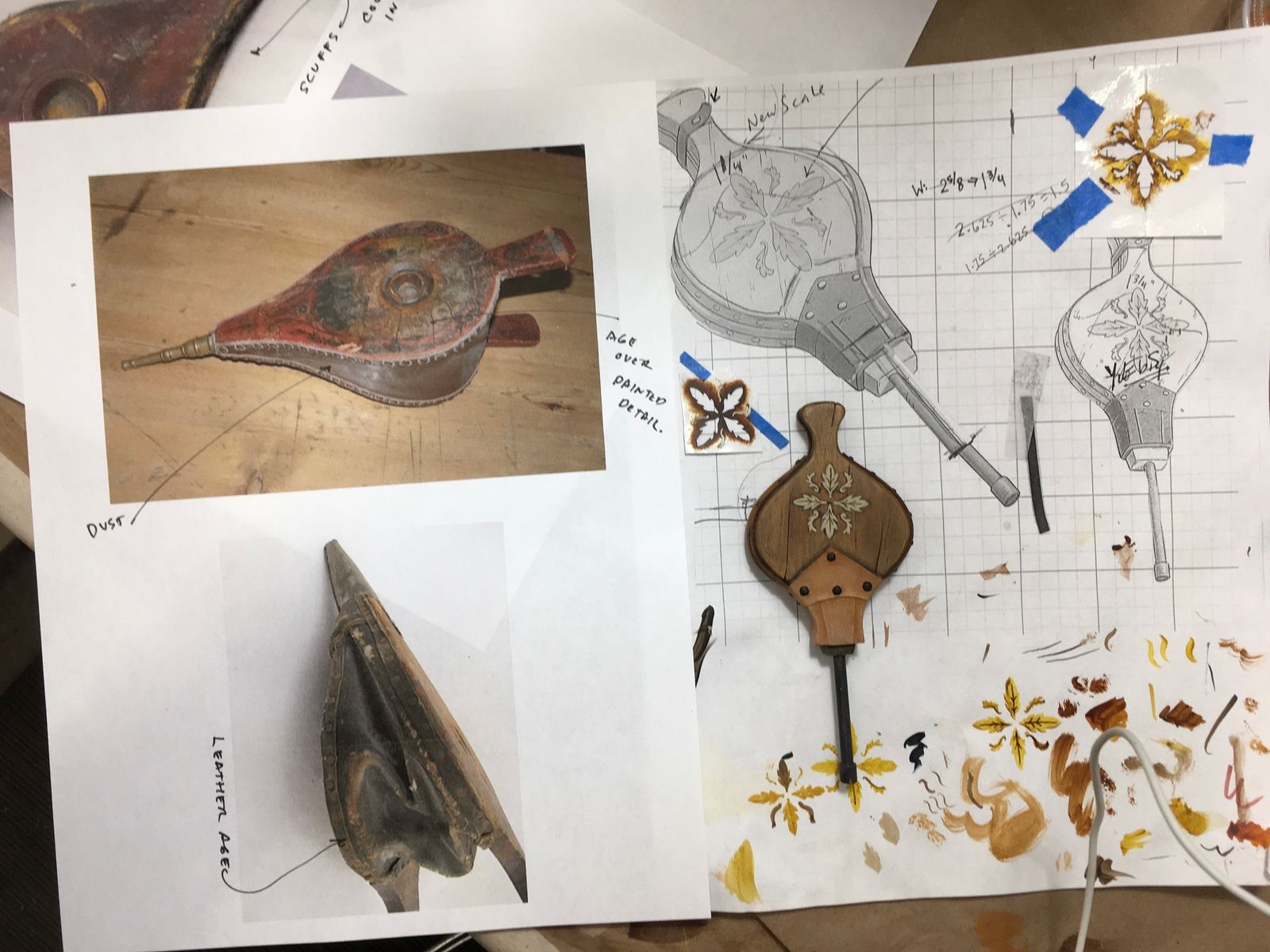

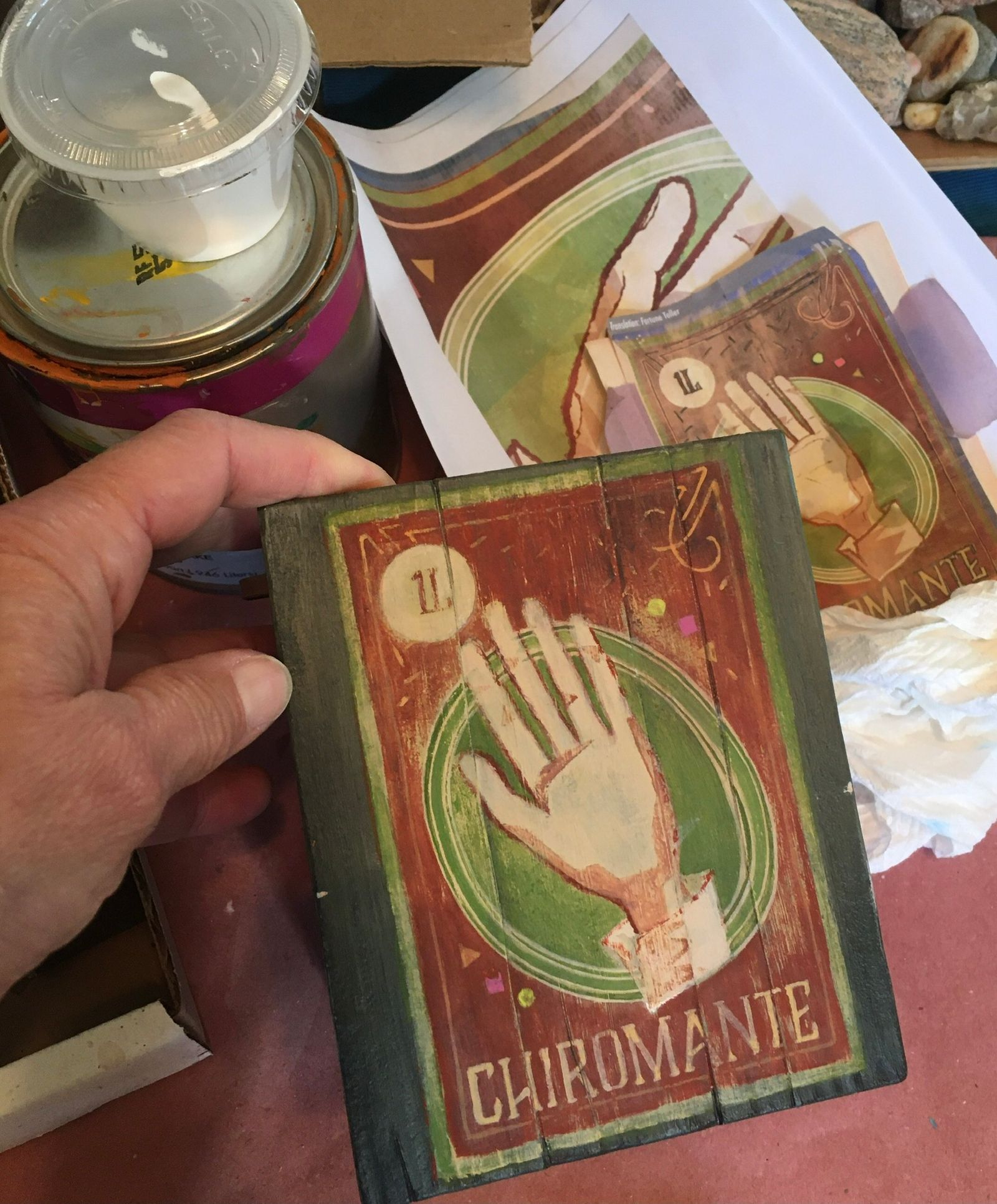

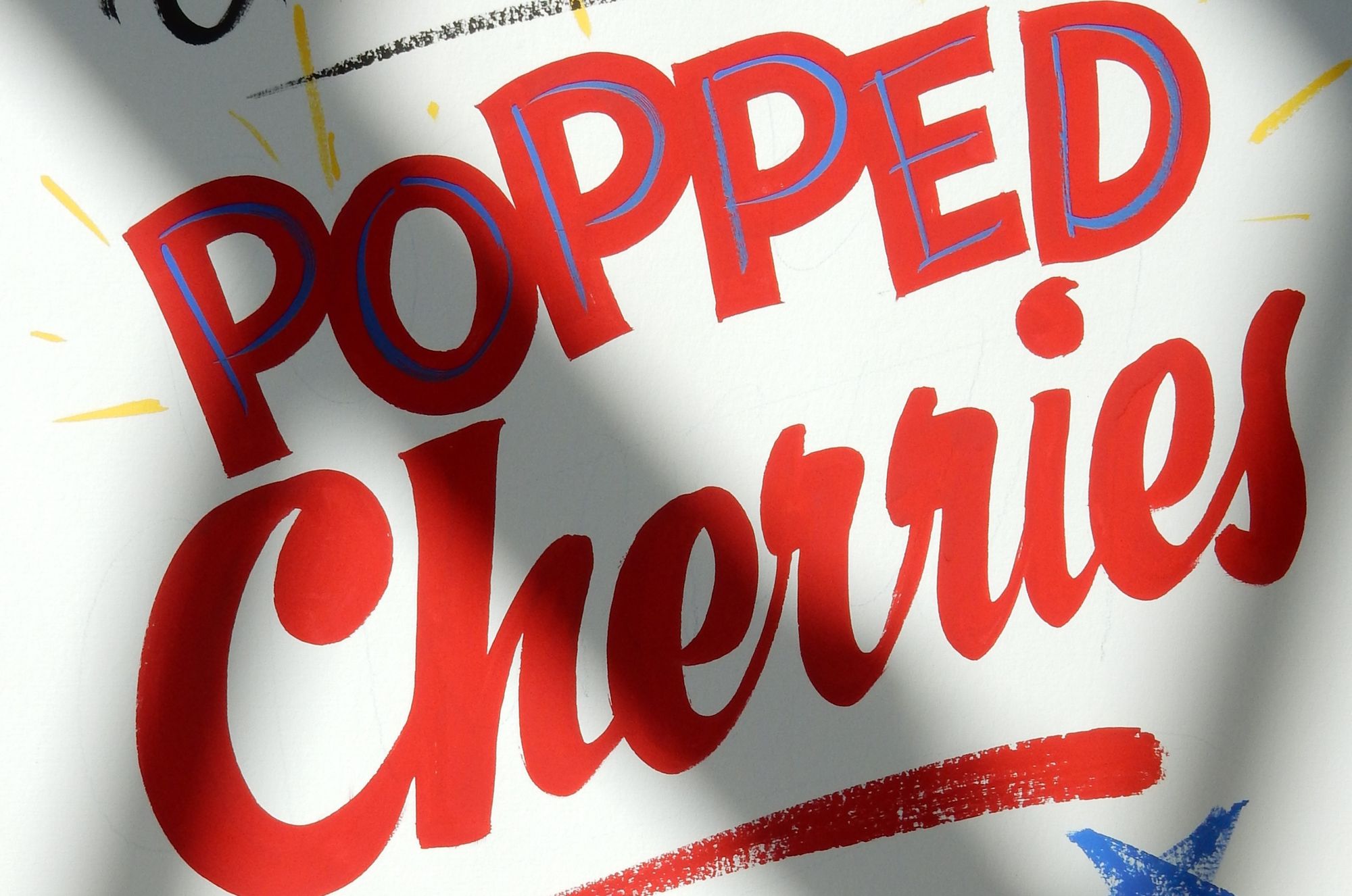

Behind the Scenic Painting of Pinocchio's Animation Oscar

|

Older messages

Your BLAG Emails Are Changing

Tuesday, April 25, 2023

This week, the format and frequency of emails from BLAG are changing. This is in response to feedback from the reader survey, and to give paid members greater control of what they receive. What does

Apprenticeships, Beverly Sign Co., and More Adventures in Sign Painting

Friday, April 21, 2023

This April 2023 BLAG newsletter features a bumper five new online articles, details of a very special book on Kickstarter, an events roundup, and a 'Ghost Sign Corner' with a direct link to our

Now Booking: BLAG Events

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

I've added a new programme of online events to the BLAG print and online publication. These events provide another way for you to access a world of sign painting experience and expertise beyond the

Site (and Events) Working Again

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

Immediately after sending today's email about BLAG Events, I was made aware of an issue with the bl.ag site. This is now fixed, and the links in the email should work again. Sorry for filling your

Get Your Hands on BLAG 02 (Limited Stock Remains)

Thursday, March 30, 2023

The limited remaining stock of Issue 02 of BLAG (Better Letters Magazine) is now available to buy in the online shop. As a newsletter subscriber, you are receiving this news before it is shared on

You Might Also Like

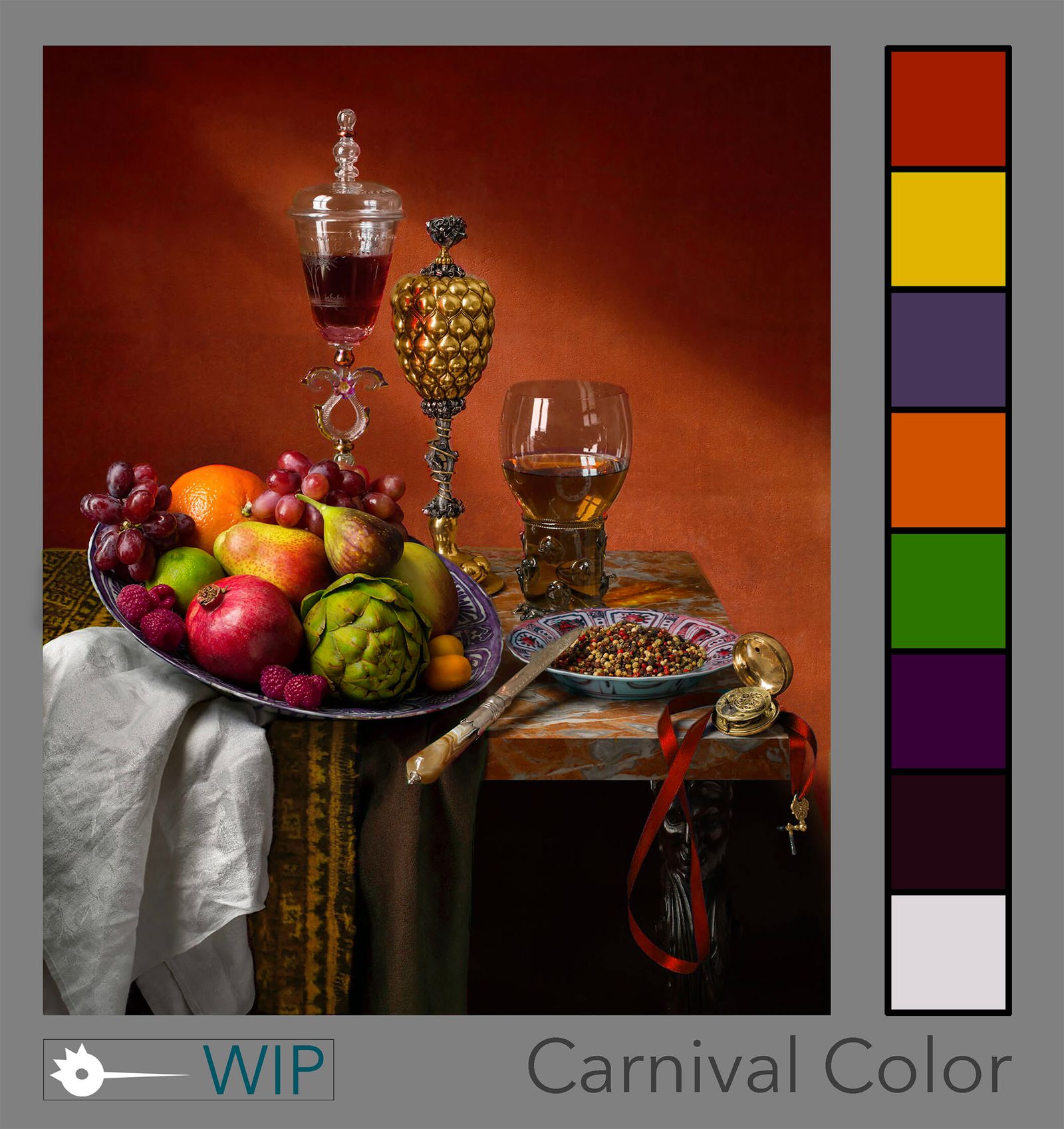

Red Hot And Red

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

What Do You Think You're Looking At? #204 ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What to Watch For in Trump's Abnormal, Authoritarian Address to Congress

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Trump gives the speech amidst mounting political challenges and sinking poll numbers ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

“Becoming a Poet,” by Susan Browne

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

I was five, / lying facedown on my bed ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Pass the fries

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

— Check out what we Skimm'd for you today March 4, 2025 Subscribe Read in browser But first: what our editors were obsessed with in February Update location or View forecast Quote of the Day "

Kendall Jenner's Sheer Oscars After-Party Gown Stole The Night

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

A perfect risqué fashion moment. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 3.3.2025 Now that award show season has come to an end, it's time to look back at the red carpet trends, especially from last

The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because it Contains an ED Drug

Monday, March 3, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It Contains an ED Drug The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It

10 Ways You're Damaging Your House Without Realizing It

Monday, March 3, 2025

Lenovo Is Showing off Quirky Laptop Prototypes. Don't cause trouble for yourself. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY 10 Ways You're Damaging Your

There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood

Monday, March 3, 2025

Today in style, self, culture, and power. The Cut March 3, 2025 ENCOUNTER There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood A Sex Education fan favorite, she's now breaking into Hollywood on The White Lotus. Get

Kylie's Bedazzled Bra, Doja Cat's Diamond Naked Dress, & Other Oscars Looks

Monday, March 3, 2025

Plus, meet the women choosing petty revenge, your daily horoscope, and more. Mar. 3, 2025 Bustle Daily Rise Above? These Proudly Petty Women Would Rather Fight Back PAYBACK Rise Above? These Proudly

The World’s 50 Best Restaurants is launching a new list

Monday, March 3, 2025

A gunman opened fire into an NYC bar