Geoffrey, Meredith, Raymond, René, Richard, and James

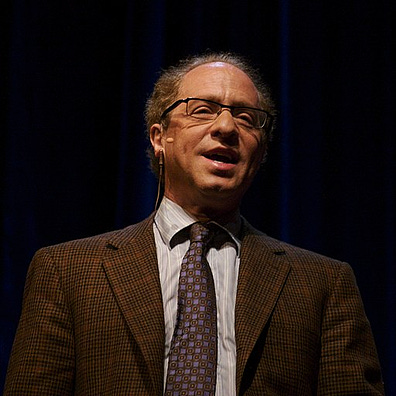

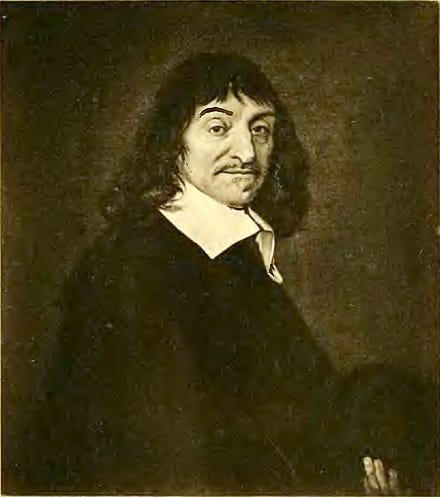

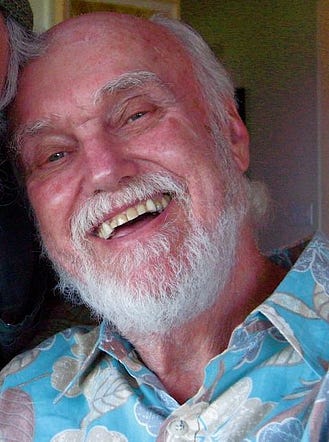

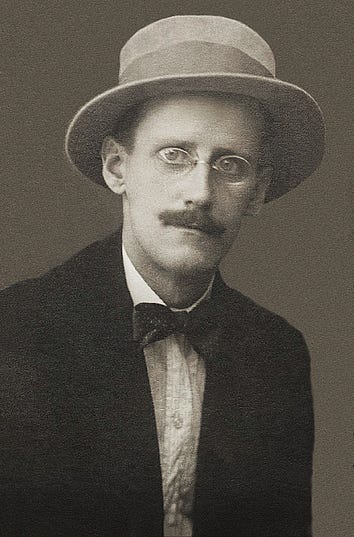

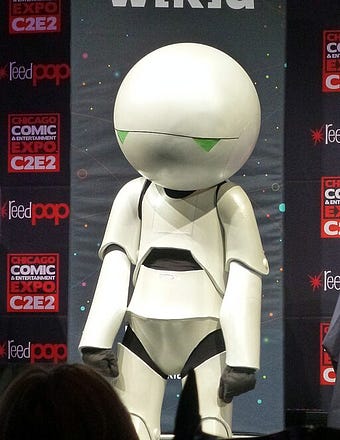

Geoffrey Hinton is a computer scientist who’s done decades of really amazing work on “artificial intelligence,” even though he never managed to get that stupid term (“artificial intelligence”) changed. Most people hadn’t heard of him until he recently resigned from Google, where he was something like the lead AI guy, and started criticizing his chosen field. He’s one of the tech bros who seem to think that we should step away from AI, at least for a while, because he’s just recently grown afraid of it, and how it might hurt humanity. Or what he thinks of as humanity, anyway. Meredith Whittaker used to work at Google too, and she calls bullshit on Hinton by pointing out that AI applications have been hurting humanity for some time now. Just now what Hinton thinks of as humanity. She notes that “harms [from AI] that are happening now—… are felt most acutely by people who have been historically minoritized: Black people, women, disabled people, precarious workers, et cetera.” Whittaker goes on to say that when she listens to Hinton, what she hears is “if a sci-fi fantasy came to life and AI were actually super intelligent, … suddenly men like me would not be the most powerful entities in the world, and that would affect my business.” Ray Kurzweil is an inventor, entrepreneur, and author who signed on to the idea of a “technological singularity.” The idea came, as far as I know, from computer scientist John von Neumann, was popularized by writer Vernor Vinge, and further popularized by Kurzweil himself in The Singularity is Near. The idea is that an artificial intelligence program actually gets intelligent and starts upgrading itself (or writing even more intelligent computer programs). After that point — which is the singularity — we don’t have any idea what comes next; it’s beyond our ability to predict. And by the way, what Kurzweil and company mean, at least in part, when they use the word “predict,” comes from another Kurzweil book, 1999’s The Age of Spiritual Machines: he predicted that computers would become able to make more profitable investment decisions than humans. That sounds like the source of an eventual complaint, like what Marvin the depressed robot said in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: “Here I am, brain the size of a planet, and they tell me to take you up to the bridge. Call that job satisfaction? 'Cos I don’t.” The singularity, of course, isn’t anything new. Plenty of societies and religions have believed in similar things throughout history. One thing nearly all of them include — and this is one of the things Kurzweil is really intent on, to the extent that he takes something like 100 diet supplement pills per day — is eternal life. In ancient societies that was provided by magic or gods or spirits, but our modern version is supposed to come from science. Except there really isn’t any science that offers eternal life, or superintelligence, or any outcomes like those. It’s almost like “science” becomes some sort of verbal shorthand meaning “at this point stuff just happens. It’s too fancy for me to explain to you, but just trust me on this.” René Descartes has a lot to answer for. He’s the genius polymath from the 1600s who came up with a whole lot of the thinking that underlies our outlook these days. “I think, therefore I am,” is one fundamental idea that virtually everybody has heard, and it seems on the face of it to be pretty straightforward. I mean, thinking is how you know you’re…um, thinking? And if you weren’t able to think, then…what? One of the ideas put forth by the technological prophets like Kurzweil and Hinton and company is eternal life by uploading your mind into a computer. Becoming an AI yourself. You’ll still be able to think, you see, so you might still “be.” Sort of. In 1971, Ram Dass, who was born Richard Alpert, published a book called Be Here Now. I have to admit that I’ve never read it. But I very much like the title, which is an exceptionally powerful idea even though it’s stated so simply. Just be present. Fully aware. The more recent term for this is “mindful,” although I don’t think it’s any better, just newer. Being completely in the present moment is a very difficult accomplishment. It calls for being aware of yourself — fully aware. And aware of what’s immediately around you. And also aware of what’s not immediately around you. You have senses that can help; hearing the air moving past, seeing light reflect and refract, smelling a lilac bush or diesel fumes. You also have a mind that can help, although it often seems like it really doesn’t want to. It will distract you, try to zero in on just one thing instead of all the things, and come up with countless thoughts that aren’t here or now at all, but compete with the thoughts that are. It’s your mind that makes it such hard work to “be here now,” or at least it is for me. I can manage it, but only for short stretches at a time. It’s hard work. The rest of the time I’m basically just not paying attention, not completely. I’ve come to believe that when I’m not “here now,” when I’m not paying full attention, my mind is impoverished. It doesn’t think it is, of course. It thinks it’s the center of everything, and likes the recursive attention. Recursive, that is, because it’s the mind itself that’s paying the attention. But regardless of its self-regard, in those moments it’s an impoverished mind. James Joyce published Ulysses in 1922. It’s a difficult book to read. It doesn’t have a conventional plot, it has a lot of unconventional language and idiosyncratic structure, and it bears down — hard — on the here and now. That here and that now being Dublin, Ireland, on June 16, 1904, and the experiences of Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom. Joyce manages to depict what “being here now” is like when it’s laid out in language. It’s hard enough trying to be fully present for oneself; I don’t know how Joyce managed to do it in print, using fictional characters. Ulysses made people uncomfortable, and probably still does. If you’re going to be fully present, you’re aware of all the passing urges and sensations in your body, the distractions in your mind, the messages from your senses, and the things all those sensations remind you of. It’s an entire book that tries to stand against the notion of an impoverished mind, and in its way it refutes the Cartesian ideas that you “are” because you think, and that your mind and body are somehow separate. You are, it says, because you are. I really have no idea whether this next thing is true, but I’m going to say it anyway: I bet people like Geoffrey Hinton and Ray Kurzweil — and tech bros like them — have never read Ulysses. They are technically brilliant people, and capable of remarkable feats of thinking, but for all that, they’re suffering with impoverished minds. I’m not sure they could imagine this, so try to do it for them: you really do manage to separate your mind from your body and upload it into a computer. All those sensations and urges and drives and half-felt feelings stay behind because there’s nowhere for them to go. All you have is your “mind,” whatever that might be, in the sterile silicon silence. Forever. Or at least until some idiot trips over the power cord. I’m surprised Marvin the depressed robot wasn’t a lot more depressed. If you liked this issue of Feake Hills, Crooked Waters, please share it! |

Older messages

Value Parasites and How to Avoid Them

Saturday, May 13, 2023

Enshittification takes many forms

That Ancient-Time Religion

Sunday, May 7, 2023

Or is it new age?

I've grown accustomed to your issue

Tuesday, April 25, 2023

We can get used to anything except getting used to things

The GPT Issue

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

Maybe we should have a little chat

Gooey and sticky

Saturday, December 10, 2022

Too many sweets are bad for you

You Might Also Like

eBook & Paperback • Demystifying Hospice: The Secrets to Navigating End-of-Life Care by Barbara Petersen

Monday, March 3, 2025

Author Spots • Kindle • Paperback Welcome to ContentMo's Book of the Day "Barbara

How Homer Simpson's Comical Gluttony Saved Lives

Monday, March 3, 2025

But not Ozzie Smith's. He's still lost, right?

🧙♂️ Why I Ditched Facebook and Thinkific for Circle (Business Deep Dive)

Monday, March 3, 2025

Plus Chad's $50k WIN ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

I'd like to buy Stripe shares

Monday, March 3, 2025

Hi all, I'm interested in buying Stripe shares. If you know anyone who's interested in selling I'd love an intro. I'm open to buying direct shares or via an SPV (0/0 structure, no

What GenAI is doing to the Content Quality Bell Curve

Monday, March 3, 2025

Generative AI makes it easy to create mediocre content at scale. That means, most of the web will become mediocre content, and you need to work harder to stand out. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

mRNA breakthrough for cancer treatment, AI of the week, Commitment

Monday, March 3, 2025

A revolutionary mRNA breakthrough could redefine medicine by making treatments more effective, durable, and precise; AI sees major leaps with emotional speech, video generation, and smarter models; and

• Affordable #KU Kindle Unlimited eBook Promos for Writers •

Monday, March 3, 2025

Affordable KU Book Promos "I'm amazed in this day and age there are still people around who treat you so kindly and go the extra mile when you need assistance. If you have any qualms about

The stuff that matters

Sunday, March 2, 2025

Plus, how to build a content library, get clients from social media, and go viral on Substack. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Food for Agile Thought #482: No Place to Hide from AI, Cagan’s Vision For Product Teams, Distrust Breeds Distrust

Sunday, March 2, 2025

Also: Product Off-Roadmap; AI for PMs; Why Rewrites Fail; GPT 4.5 ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Pinterest For Authors 📌 30 Days of Book Pins 📌 1 Each Day

Sunday, March 2, 2025

"ContentMo is at the top of my promotions list ... "I'm amazed in this day and age there are still people around who treat you so kindly and go the extra mile when you need assistance. If