👋 Hey, Lenny here! Welcome to this month’s ✨ free edition ✨ of Lenny’s Newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career.

If you’re not a subscriber, here’s what you missed this month:

How today’s top consumer brands measure marketing’s impact

How Shopify builds product

What is good free-to-paid conversion

Subscribe to get access to these posts, and every post.

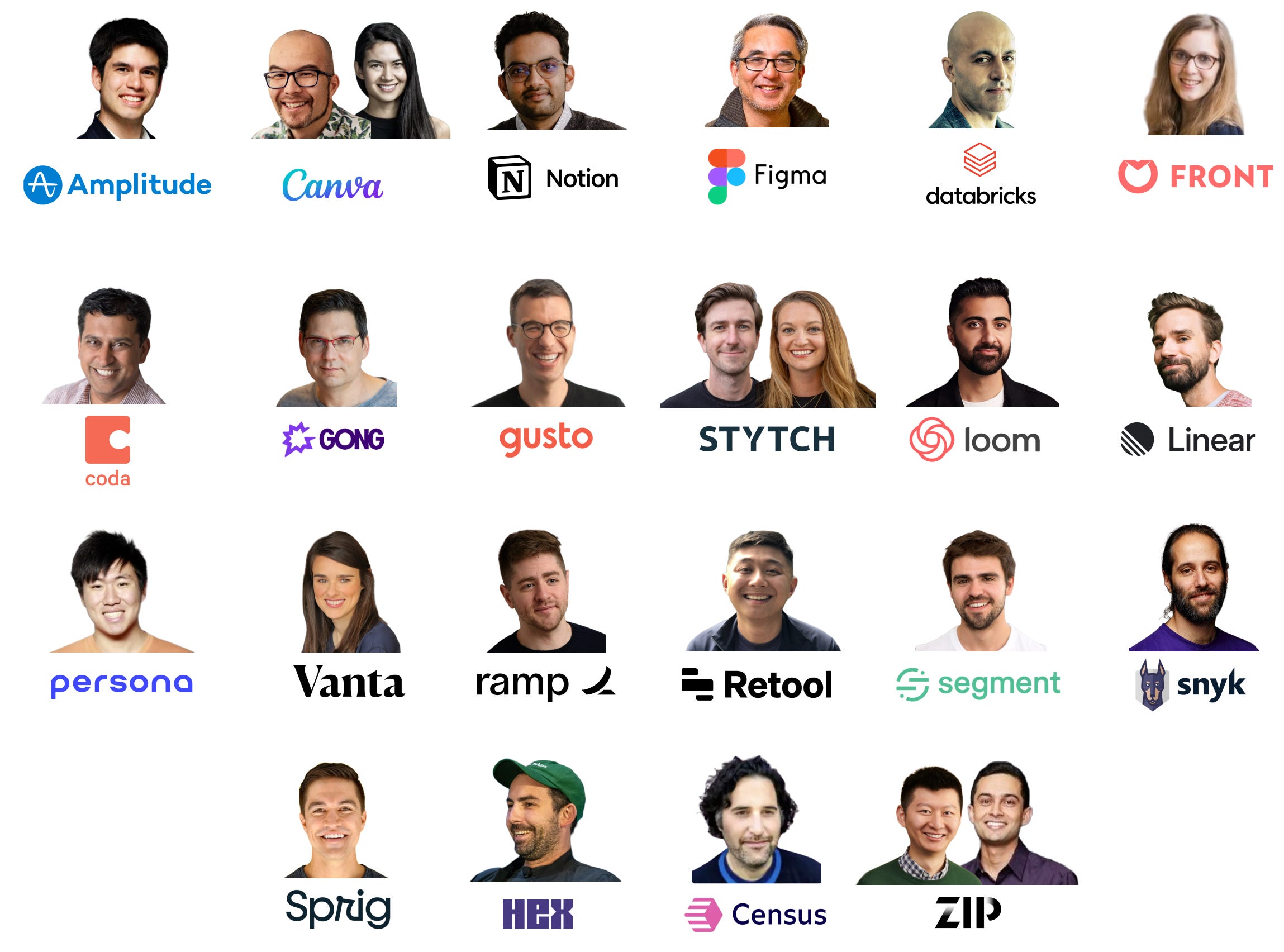

My paternity leave has come to an end, and I’m kicking things up a notch. Over the next two months, I’m going to share a multi-party in-depth playbook for kickstarting and scaling a B2B business. This series took hundreds of hours of work and is based on dozens of 1:1 interviews with the founders of two dozen of today’s most successful B2B companies—including Gong, Notion, Figma, Amplitude, Retool, Canva, and many more. In addition to these juggernauts, I’ve also pulled in a handful of my favorite up-and-coming B2B startups, including Linear, Vanta, Stytch, Zip, Census, Persona, and Hex.

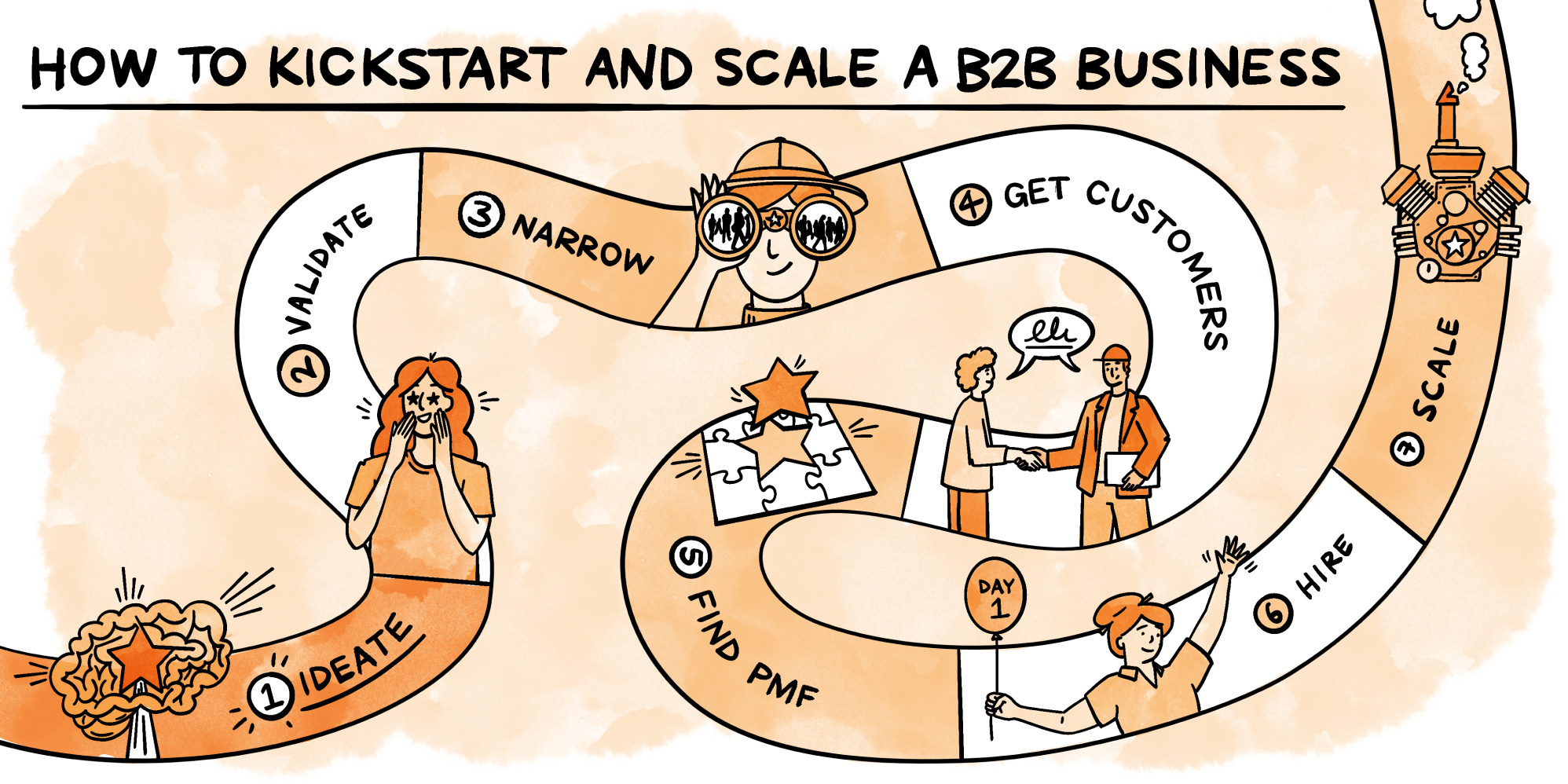

This series builds on my two previous playbooks—for consumer businesses and marketplace businesses—and brings me one step closer to my goal of giving every founder a tactical guide for turning their idea into reality. Even if you’re not building a B2B startup right now, you’ll find inspiration, new ideas, and frameworks that will help you with the product you’re building right now. Here is what’s in store:

Part 1: How to come up with a great B2B startup idea ← This post

Part 2: How to validate your idea

Part 3: How to identify your ICP

Part 4: How to find and win your first 10 customers

Part 5: How to find product-market fit

Part 6: How, and when, to hire your early team

Part 7: How to scale your growth engine

You’ll find never-before-shared stories, surprising lessons, and as usual—a ton of tactical and actionable advice you can use to grow your own product today.

Here’s a peek at a few of the more surprising takeaways:

The majority of founders had no special skill or background in the problem space they went after.

Most B2B startup ideas did not come from the founder feeling the pain at their last gig (though many did).

Every prosumer product (e.g. Notion, Figma, Airtable, Miro, Slack, Coda) took two to four years of wandering in the dark before they found something that worked.

Founders spoke to a median of 30 potential customers to validate their idea, before committing.

~40% of startups pivoted at least once before landing on their winning idea—often times more than once.

About 20% were solo founders.

Cold outbound works—it’s the second most common way to get your early customers.

This series should probably be a book, but instead, I’m sharing it with you all here. I’m excited to hear what you think and evolve this work further. And remember: following these steps (or any steps!) won’t guarantee success. But, it’ll certainly improve your odds. Let’s get started with step one—coming up with a great idea.

A huge thank-you to Akshay Kothari (COO of Notion), Ali Ghodsi (CEO of Databricks), Barry McCardel (CEO of Hex), Boris Jabes (CEO of Census), Calvin French-Owen (co-founder of Segment), Cameron Adams (co-founder and CPO of Canva), Christina Cacioppo (CEO of Vanta), David Hsu (CEO of Retool), Eilon Reshef (CEO of Gong), Eric Glyman (CEO of Ramp), Guy Podjarny (CEO of Snyk), Jori Lallo (co-founder of Linear), Julianna Lamb and Reed McGinley-Stempel (co-founders of Stytch), Mathilde Collin (CEO of Front), Rick Song (CEO of Persona), Rujul Zaparde and Lu Cheng (co-founders of Zip), Ryan Glasgow (CEO of Sprig), Shahed Khan (co-founder of Loom), Shishir Mehrotra (CEO of Coda), Sho Kuwamoto (VP of Product of Figma), Spenser Skates (co-founder and CEO of Amplitude), and Tomer London (co-founder and CPO of Gusto) for contributing to this series. Art by Natalie Harney.

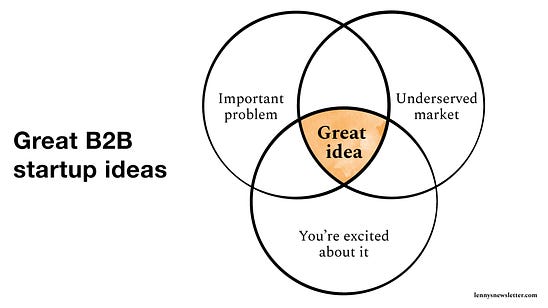

If you boil it down, there are essentially three elements to a great B2B startup idea:

There needs to be a lot of people willing to spend a lot of money to solve the problem. Most startups fail not because the idea isn’t good, but because the market for the solution is just too small. If you want to build a venture-scale business, a rule of thumb is that there needs to be a clear path to $100m in revenue/year, and eventually a path to $1B/year. Here’s a great example of what you want to see, as told by Ryan Glasgow, CEO of Sprig:

“Robinhood agreed to a large contract even though we were early. They’re like, ‘We love it. We’ll install tomorrow.’ They installed it as we were building the first version.”

Hunter Walk has a great framework called LUV. Also, here’s my take on what makes a venture-scale idea, and a guide to help you think through your market size.

Existing solutions need to be doing a subpar job of solving the problem. The founder of CRED, Kunal Shah, has a great framework for evaluating potential new solutions called Delta-4:

What would a customer rate the existing solution on a scale of 1 to 10?

What would they rate your solution?

Your solutions needs to be 4+ better for anyone to care about your product.

This also means that if the existing solution gets a 6 or higher, it’ll be very hard to replace (e.g. Excel). Here’s what you’d love to see, as shared by Tomer London, co-founder of Gusto:

“As soon as we asked them the simple question of how they feel about their current payroll provider, they started cursing. More than half of the people we talked to just started cursing, unprompted. Two people voluntarily told me, ‘I use [competitor name], and my password is fuck[competitor name].”

Finally, the problem needs to be something you are willing to spend many years of your life solving. This advice from Dylan Field, co-founder of Figma, captures the sentiment perfectly:

“There are actually a lot of good ideas out there. It’s kind of the weird part, especially if you’re searching for one; it feels like it’s not the case, but there are so many different markets that are underserved. The more important thing, actually, is to find something that you are personally passionate about, because any good company takes a long time to build.

If you are, let’s say, three to four years in on an idea that you hate, you’re just going to burn out and you’re going to quit. It won’t feel good and you’ll be hating life. Don’t just go for an idea because it’s kind of working. Go for an idea that you really care about, because even if it doesn’t work, you’ll still learn from it and you’ll still have one.” —Dylan Field, co-founder and CEO of Figma, via Elad Gil

Takeaway: Find an idea that solves a problem that is important, underserved, and that you’re excited about. You’ll hear a lot more about how to do this, and what this looks and feels like, below.

“It's essential to work on something you’re deeply interested in. Interest will drive you to work harder than mere diligence ever could. When in doubt, optimize for interestingness.”

—Paul Graham

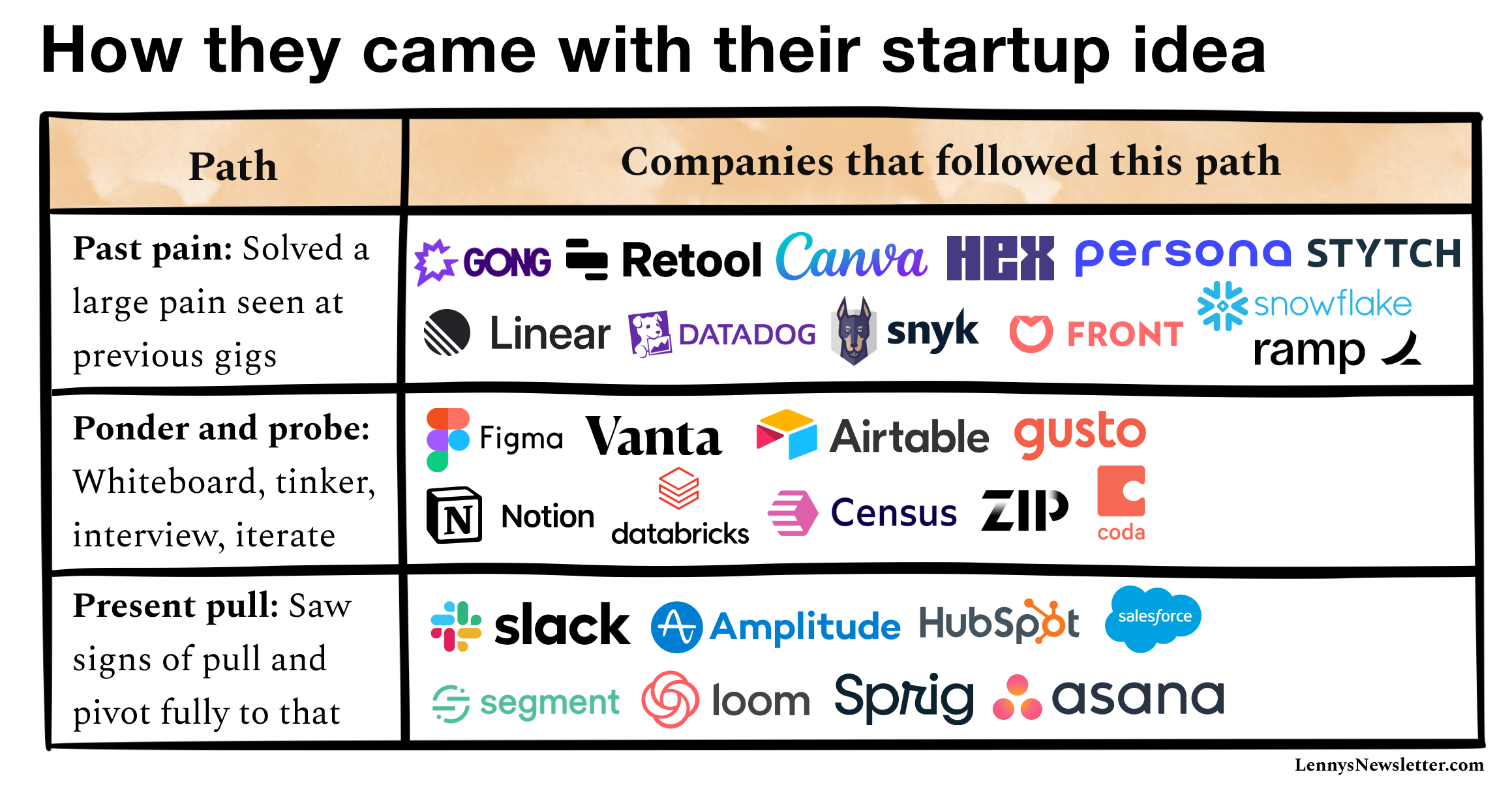

Across all of the interviews I did, I found three reliable paths for discovering a great idea:

Past pain: Identify a large pain you experienced at a previous company—then build a solution.

Ponder and probe: Pick a space you’re interested in, then whiteboard and tinker while talking to dozens of potential customers—looking intently for pain and pull.

Present pull: Identify something you’ve built that is showing signs of pull—and pivot fully to that.

Here’s an overview of how today’s biggest B2B companies found their ideas:

No matter which path you take, you are looking for two things: pain and pull. Pain tells you there’s an opportunity to solve a problem, and that it’s important. Pull tells you that you’re actually solving the problem.

Let’s explore each of the three paths, illustrated by founder stories.

When I first started this research, I was expecting this path to be the way that all great startups found their ideas. Surprisingly, it only accounts for about 40% of great ideas.

Let’s consider five successful startups that found their big idea following the path of past pain: Gong, Retool, Linear, Persona, and Hex.

The CEO of Gong experienced the pain of being unable to understand what was going wrong within the sales process at his previous company:

“Amit, now my co-founder, ran a company in the BI space called Sisense. He ran into a problem: when sales didn’t work well, and it was very hard to understand why. He realized that essentially all of the knowledge about what was working and not working was hidden inside people’s heads: ‘The CRM was showing me stuff, but it wasn’t anything meaningful. Yes, you didn’t close that deal, but why?’

He left Sisense and looked around to see if anybody was addressing this problem. I was on sabbatical doing nothing, learning deep learning, so we figured: let’s try to come up with a system that takes the stuff from salespeople’s heads, captures the information, and gives visibility and guidance to the rest of the organization.”

—Eilon Reshef, co-founder and CEO

David Hsu, the founder of Retool, found himself building the same product over and over at each company he worked at:

“Perhaps a little-known fact is that I had actually started a couple of other companies and products before Retool. And every time the team built any of these products, we had to go build our own tools for it. Eventually, when you build enough of the same things—in this instance, internal tools for different projects—you kind of realize they actually all have the same building blocks. We thought, ‘There’s got to be a better way of doing this.’ And we’re lazy engineers and we thought other engineers would be lazy as well. So that’s how the idea [for Retool] first came about.”

—David Hsu, founder and CEO

The founders of Linear felt deeply disappointed every time their companies defaulted to Jira:

“Linear emerged out of the pain we all felt with issue tracking project management, when it comes to building software. I was at a time at Coinbase, Karri was at Airbnb, Tuomas was at Uber. We were all at these growth-stage companies and saw how they both grow and operated as they grew.

I very vividly remember the time around 2016 at Coinbase, when we were closing in on 100 people, and we hired a VP of engineering. There was a desire to start unifying the teams using a single tool. And Jira started coming up in the conversations.

I was maybe a little bit naive and tried to keep my team using Trello, but I very quickly realized that it is a losing battle. You’ve just got to go with it and there’s no other solution basically on the market. And so we ended up going with Jira. But it just stayed with me as this nagging feeling of disappointment.

Separately, Karri at Airbnb had created a Chrome extension to re-skin their Jira, and Tuomas was building developer tools at Uber, using Fabricator. We all had similar experiences of ‘this doesn’t feel right and we should do something about it.’”

—Jori Lallo, co-founder

Persona’s founder noticed how inadequate identity tooling was when having to build this technology at Square:

“I worked on identity over at Square for a fair bit of time. We actually used to joke as a collective team over on Square, ‘I’m sure in 10 years there will be someone who does this well for us.’ Importantly, while we were building it, we noticed that there was this disconnect between existing identity vendors thinking that there was going to be one technique that’ll solve all of a customers’ identity problems, while in reality, every business had a multi-modal approach: a bunch of different techniques to verify different people in different contexts. So we saw an opportunity to go after this problem in a unique way.”

—Rick Song, co-founder and CEO

Hex’s founder realized that no one was going to build what he needed, so he had to do it himself:

“I actually started this journey as a buyer. I was looking for something like Hex and I couldn’t find it. It took me a few months of going around and talking and asking people like, ‘Oh, what are you using for this? What are you using for that? Have you found anything good for this?’ Everyone said, ‘No, but if you do, let us know.’ It kind of clicked one day. I was like, ‘Well, maybe we should do this.’

I didn’t set out to be a founder. There are a lot of people out there who are like, ‘I want to be a founder. I just need an idea and a co-founder.’ I was almost the opposite. The idea was very obvious to me. I had two great co-founders that I had met at Palantir whom I loved working with. It almost took us a while to be like, ‘All right. I guess we have to do this. Don’t we? No one else is doing this, while we have to do it.’”

—Barry McCardel, co-founder of Hex

Takeaway questions to reflect on:

What did you or others build at previous jobs that proved to be incredibly valuable to the company, or your teammates?

What’s a tool you wish you had (and would have paid a lot of money for) at your previous companies?

What internal products have you built again and again at past companies?

A surprisingly large number of founders came up with their startup idea by doing something that’s often discouraged: sitting around and whiteboarding. As you’ll see below, there’s a wrong way of whiteboarding and a right way (i.e. ideating and building in a silo versus quickly talking to potential users to validate your idea). But most importantly, if you want to find a great idea, again, focus on finding a problem space with three traits: (1) it’s important, (2) it’s underserved, and (3) you’re excited about it. Ideally, your idea is also rooted in some experience you’ve had in the space, but it doesn’t have to be.

Figma’s founders narrowed their focus to two areas they saw potential in and then started tinkering with the one they were most excited about—design:

“After we got the Thiel Fellowship, I called Evan and said, ‘Hey, you know, we’ve got actual funding now: a hundred thousand over two years. Do you want to go do this thing for real?’

When you’re starting a company, it’s really useful to ask the question, why now? It’s a really useful framework. It can be societal. Maybe there’s some new cultural trend; perhaps it’s regulatory. Some law has been passed or appealed. I like the technological version. For us, we saw drones in 2012 and WebGL as a few technologies that were happening. Because of them, new possibilities were suddenly there.

On the drone side, we didn’t get very far. Evan in particular was not that interested in doing hardware. He’s like, hardware sucks, run debug cycles are really long, and then we focused on WebGL instead.

We were also excited about computational photography for a bit, but quickly realized that with photos, that ends up leading to a consumer sort of application. And the entire purpose of WebGL was to be in the browser. Why would you do anything in photo editing if you’re not on the phone? And so we felt like we were kind of building in the wrong place and then eventually sort of shifted our attention to design; I had been a design intern at Flipboard, and that kind of helped me realize what would be possible there.”

—Dylan Field, co-founder and CEO, via Elad Gil

Vanta’s Christina Cacioppo similarly narrowed down her thinking to two spaces that felt ripe for opportunity that she was excited about (security and collaboration), and kept talking to customers to find the biggest source of pain and pull:

“Our first couple of ideas were just total garbage. There was a lot of whiteboarding. I think the failure mode in this part of the process with the whiteboard is that it’s just all so abstract. There were no customers or users.

Back then, I tended to be a shiny-object person, so left to my own devices, my natural inclination was just to go find all the shiny objects on the surface. So I was, okay, no, don’t do that. Pick one or two spaces and go really deep. You’re not allowed to look at anything else. Not allowed.

I chose (1) team collaboration tools, because I thought, I don’t know if I truly love this but I know it from my Dropbox days, and (2) security, because it seemed interesting and I wanted to learn it. They both seemed big and important, and interesting, and I had all kinds of security and compliance challenges at Dropbox. I also felt like I’d be happy learning about that space, and I also wanted to work with startups.

Within collaboration, we were asking ourselves, ‘What are the macro trends and new technologies shaping the world?’ It’s late 2016, and so . . . voice! Team collaboration software is also emerging, and so the answer is B2B Alexa. At the whiteboard stage, it makes so much sense. And in reality, zero sense. We recognized that if you can do it on a whiteboard, someone has probably done it. There’s no $20 bills on the sidewalk.

Also, when you’re changing context from B2B Alexa to other ideas like, I’m going to make a better wiki, to solving security, to whatever, you’re spreading yourself too thin and you’re not going deep enough to actually learn anything that someone else hasn’t.

So within the security bucket, I started asking all the startups I knew about security, and they all looked at me really guiltily and said, ‘We don’t really do anything. We know we should, but we don’t.’ Everyone wanted to do security, but it was hard to prioritize until customers asked for it. So I started doing it for them scrappily and manually, and that led to what Vanta is today.

When I tell founders this, sometimes they’re like, ‘Well, how did you know security was going to work?’ You don’t. If you know the answer to that, go for it. But it’s only obvious if you look back.”

—Christina Cacioppo, founder and CEO

Notion started with the general idea of a no-code app builder and eventually (four years later!) noticed pull for a specific set of features:

“Early Notion was basically a no-code website builder. Some of the videos actually exist in YouTube. It didn’t go anywhere for years. It was very unstable, the tech stack we had used in the early iterations of it was fairly buggy, and user feedback was not great. But as we peeled the onion, talking to users and using it ourselves, we realized that for the people that continued to use it, they liked some elements of the editor and the collaborative features that the product had. And through that, we realized that we should double down on docs and wiki.

The turning point was in early 2017 (four years in), when we launched Notion 1.0, focused around just docs and wikis. At the same time, we made a few different templates ourselves so that you can click a button and start using the product. Instead of telling people to build software using our tool, you can now click a button and get this modern docs/wiki product, without any work. It proved to be a great wedge into the market, because notes is the simplest unit of work, and it got people in the door and using the product. And then once people actually started using it, some people went down to the lower stack and they were like, ‘Huh, I can actually change these things. I can modify it, I can build my own template.’ We took a little bit of a roundabout way of getting there, but that’s the story.”

—Akshay Kothari, co-founder and COO

For Zip, Rujul Zaparde and Lu Cheng went through a variety of ideas, looking for a big and underserved market they were excited about. They eventually focused on procurement (and their company is currently valued at over $1B):

“This was actually our sixth or seventh idea. Some earlier ideas included allowing people in India (and then other countries) to be able to buy U.S. equities in a fractional way, and an accounting staffing platform (which generated $200k of revenue!).

Eventually, as we were thinking through our next pivot, the advice we got from our YC partner was to look for a market that was large and had entrenched companies that weren’t great. This led us to the procurement space.

And then we thought back to this problem at Airbnb. In hindsight, we both adjacently ran into it a couple of times, but we didn’t realize it until later.

—Rujul Zaparde and Lu Cheng, co-founders

For Databricks, Ali Ghodsi noticed a new technology emerging that was underutilized and kept talking to users until he realized how to turn it into a real company:

“We were doing research for a bunch of years at U.C. Berkeley and had started seeing what was happening in Silicon Valley tech companies, how they were solving data scalability problems, and how different their approach was from what we were seeing in the rest of the industry. At that time, the rest of the industry was leveraging this technology called Hadoop, and that was the best thing since apple pie for them. But we were seeing that the Silicon Valley tech companies were using a different technology (what is now Apache Spark) and were in fact doing AI and machine learning on data, and they were getting magical results. We knew this technology could be game-changing for the rest of the industry.

Our initial thought was, ‘Can we just take what we’re seeing over there, open source it, and publish the research, and then the whole world will adopt it and we’ve changed the world?’ We didn’t really intend to start a company. But then over the years, it was frustrating to see that we had found this software, and we had open sourced it, and we thought it was so amazing, but it wasn’t getting the uptake that we thought it deserved. And people kept telling us, ‘This is some academic project. How do we know that we can really rely on it? Is it really enterprise-ready?’ And so on. There was frustration around 2012 where we thought, if we start something, if we ourselves get behind it and we raise some money, maybe we can really actually ourselves make it happen. So that was the journey.”

—Ali Ghodsi, co-founder and CEO

Takeaway questions to reflect on:

What’s a trend that’s emerging but underserved (e.g. security, collaboration)?

What’s a transformative technology that’s emerging that’s underutilized (e.g. data scalability)?

How many potential customers have you spoken with about your idea?

How important to potential customers is the problem you’re exploring, on a scale of 1 to 10?

How underserved is the current market, on a scale of 1 to 10? And where would your solution rank? Look for a delta of at least 4.

A final path is simply to keep building what you’re building, but pay special attention to features or functionality that are showing strong pull from existing users. This may lead to shifting your approach slightly, or it may lead to a completely different product.

In the case of Amplitude, the big idea came from noticing other founders wanting access to their internal analytics tool:

“We started with a different company before Amplitude, called Sonalight, which was a voice recognition application that allowed you to send and receive text messages by talking to your phone. One of the things that was really clear to us at the time was that you should look at what people are doing in your product in order to figure out how to make it better. Figure out where people are getting stuck, what keeps them coming back, what they like to use and what they don’t like to use.

We tried out tons of products on the market. I remember Flurry, Google Analytics, Adobe, Kissmetrics, and others. And none of them were able to answer the questions I just posed. And so we said, ‘All right, well, we’ve got to build it ourselves.’ A bunch of engineers with a lot of hubris, haha. So we ended up doing that. And as we shared those insights with other companies that we knew (we were at Y Combinator at the time), they were like, ‘Wow, that’s amazing. I really need to understand that about my business.’”

—Spenser Skates, co-founder and CEO

Sprig followed a very similar story—Ryan Glasgow was building one product, but then noticed a side project seeing much more pull:

“I was exploring a startup idea, but I wasn’t quite getting the pull I expected. I went back to what I knew, which is product management, and I started asking users tough questions, like ‘Would you pay for this?’ and ‘Why do you not use this?’ In this discovery process, I wanted to add more rigor, knowing that this was a high-stakes decision (e.g. I’d be spending 10+ years of my life on it), and I found a technique called outcome-driven innovation, which adds rigor to product innovation. I was like, ‘Wow, this is mind-blowing. What if I could build a tool to help other people go through the idea maze and not build something before they de-risk the idea?’

So I built a little SDK that people could plug into their apps, with a very simple front end, that would just rotate through three questions about functionality, usability, and quality (the core questions in the framework I mentioned). It used Airtable as the back end actually, it was so simple.

I shared this with other founders that I knew, who were also trying to get their business off the ground, and gave them this spreadsheet of quality, usability, functionality, using this framework. And they were like, ‘Wow, I’m learning so much. I’d be your first customer if this was a product.’ It immediately clicked, they would say, ‘I’ll pay you for this.” This was the market pull I was looking for and I quickly pivoted to surveys.”

—Ryan Glasgow, co-founder of Sprig

The Loom founders went through two completely different products before seeing obvious pull within one unexpected feature of their app:

“Loom was the result of two previously failed attempts in the video space. Our first was a marketplace for companies to hire subject-matter experts (i.e. product managers, designers, engineers, etc.) for feedback on checkout flows, UX, sales funnel, onboarding, and more. While we saw initial revenue here, this failed to get the traction to warrant additional build time (we were already four months in at this point). The second was a SaaS tool that any company can embed on their website and get instant feedback from their users in the form of a user test. Similar to the first iteration, this failed to get any real momentum after three months, although it led us to a remarkable insight from one of our few design partners.

Three months into this second idea, we had an aha moment when a client used the product to record a video of himself summarizing all of the user tests his team had collected. That’s when it occurred to us that there could be something here.

A month later, we launched on Product Hunt and had thousands of people who’d downloaded the extension by day’s end. That made it clear to us that we should double down on this new direction, and we’ve never looked back.”

—Shahed Khan, co-founder

With Segment, nothing was working for a year and a half, and while throwing ideas against the wall, one idea finally stuck:

“We originally applied to YC with the idea for a university classroom lecture tool (we were college students at the time), and we built that out over the course of the summer. It failed because we aren’t good at identifying real problems, and we decided that one reason is that we didn’t understand our users.

We spent about 15 months pivoting and building various analytics products to help better understand users. None of them really took off, and we keep chasing the next idea that will get us users. As a growth hack, my co-founder Ilya built a little library called Analytics.js. The idea was that users can use it as a ‘drop-in replacement’ for Mixpanel or Kissmetrics and send us the exact same data as you would to each of them via one library. Users didn’t care much about our tool, but they seemed to like the idea of Analytics.js.

Finally, we have about six months of runway left and we haven’t launched anything. My co-founder Ian thinks that the idea behind Analytics.js could actually be a big deal. We could effectively be the ‘API layer’ over all these annoying and similar-but-inconsistent data tools.

We’re split on the decision. Peter thinks it’s the worst idea he’s ever heard and that there’s zero chance a company could be made from 100 lines of JavaScript. We all agreed to build it for a week and launch it on Hacker News. That day, it goes straight to the top of HN, and the rest is history.”

—Calvin French-Owen, co-founder of Segment

And famously, for Slack, the big idea came from noticing one feature being incredibly popular within their ill-fated video game:

“We came to the conclusion that Glitch [game he was working on] was never going to be the kind of business that would have justified the $17.2 million in venture capital investment [that we raised]. It might have been a neat project for a half-dozen people, if we had spent a million dollars to get there, but by the end of 2012, there were 45 people working on it, we had spent many millions of dollars, and it just wasn’t ever going to scale. So we decided to shut it down without knowing what we were going to do next.

The company still had millions of dollars left in the bank, and one of the possibilities was to return that money to the shareholders and call it a day, maybe start something else up. But because we had that money, we had the flexibility to shut it down in what we felt like was a humane way. We spent a long time working on reference letters for the employees who built the website, essentially to make sure that they all got jobs.

We also gave users the choice to get a refund for everything they had spent, to let us keep the money or donate it to charity. We kind of had our hands full for a little while in shutting the game down, and while we did that, we were thinking about what we might want to do next. There were all kinds of ideas.

It took us a little while to settle on the idea that would become Slack.

That was really born out of the style of communication that developed while we were working on the game. We used an older technology called IRC, and because IRC is very limited, over the years we added the little features here and there that we wanted.

For example, in IRC, if you’re not online at the same time as me, I can’t send you a message. I have to wait until you are also connected. So one of the first things we did was build a way of archiving messages so that you could catch up when you came back online, and in those archives we wanted to be able to search them, so we added search, and so on. There was no good iPhone client, so we made an HTML5 front end for our archive viewer.

This interesting dynamic happened. By the time we shut down the game, again there were 45 people at the company, we had been in operation for three and a half years, and we had a companywide email list. After more than three years, it only had 50 messages on it, so about one every three weeks. That wasn’t a deliberate decision, that wasn’t ideologically driven. But it just happened that everyone paid attention to IRC, and the more people paid attention to it, the more information we routed to it; and the more information we routed to it, the more people paid attention to it. So eventually, everything from database alerts to daily sales figures were being pumped into IRC. Every time someone uploaded a file to the file server, that would be posted into IRC. While we weren’t successful in making the game, we were very efficient in being unsuccessful to make the game.”

—Stewart Butterfield, founder, via Business Insider

Takeaway questions to reflect on:

Of all the things you’ve built, what one feature is showing the most pull?

What problem are you currently facing with your startup that you wish someone would solve? Explore solving it yourself.

What’s a side project you’ve been wanting to build that you haven’t?

Look for ideas that are (1) important, (2) underserved, and (3) you’re excited to solve.

Pick one of these routes and ask yourself these questions

Past pain

What did you or others build at previous jobs that proved to be incredibly valuable to the company, or your teammates?

What’s a tool you wish you had (and would have paid a lot of money for) at your previous companies?

What internal products have you built again and again at past companies?

Ponder and probe

What’s a trend that’s emerging but underserved (e.g. security, collaboration)?

What’s a transformative technology that’s emerging that’s underutilized (e.g. data scalability)?

How many potential customers have you spoken with about your idea?

How important to potential customers is the problem you’re exploring, on a scale of 1 to 10?

How underserved is the current market, on a scale of 1 to 10? And where would your solution rank? Look for a delta of at least 4.

Present pull

Of all the things you’ve built, what one feature is showing the most pull?

What problem are you currently facing with your startup that you wish someone would solve? Explore solving it yourself.

What’s a side project you’ve been wanting to build that you haven’t?

You know you’re on to something when you notice pull and pain.

Now that you have a framework for coming up with an idea, the next step is to figure out if the idea is worth going all-in on. Next week: How to validate your idea.

Have a fulfilling and productive week 🙏

Snyk’s Guy Podjarny noticed a couple of emerging trends and pain points in two previous jobs and began tinkering with the idea:

“Between 2002 and 2010, I helped build and manage some of the very first Application Security (AppSec) products, which customers used to find and fix AppSec vulnerabilities. Since it was very expensive to fix flaws you found at the end of a year-long release cycle, we tried to get security to ‘shift left’—to find issues during development where it’s cheaper to fix them.

I left that path to found my first startup, Blaze, building a real-time web page compiler that made websites faster. Blaze was acquired by Akamai, where I became the CTO of the web performance business. DevOps played a key role in that journey, and the perspective helped me appreciate the impact it will have on the industry—and the opportunities it brings.

These two lenses made me realize two things:

At the pace of DevOps, getting developers to embrace security has gone from an efficiency and costs play to a necessity. It’s the only way for software to be secure.

If you build the right solution, developers can and will embrace security. DevOps had proven that by getting developers to embrace ops, with tools like New Relic, Heroku, and others paving the way.

So after leaving Akamai, I set out to build a developer tooling company that tackled security.”

—Guy Podjarny, founder and CEO

All three of Canva’s founders noticed a gap in the design space:

“Mel [co-founder and CEO] was teaching design through university, including how to use different types of design software, and through that experience, she realized that it was quite complicated and really hard for people with no design background to start approaching these tools and actually get something useful out of them.

And I’d created a lot of creative tools over the previous decade, which I found unlocked people’s creativity in a whole bunch of different ways, like with music and drawing, and other creative tools. I’d worked at Google on a product called Google Wave, which was all about communication and collaboration, and again, being able to unlock people’s creativity through new technology and new experiences.

When I met Mel and Cliff [other co-founder] in 2012, the idea of unlocking design and creativity really captured all of our imaginations, and so we decided to band together in July 2012 and start building that first product. We eventually launched Canva in August 2013, about a year later.”

—Cameron Adams, co-founder and CPO

Same story for Stytch:

“We had a monthly coffee chat on our calendar after Julianna left Plaid to go to Very Good Security. We were always just catching up and often complaining about work, what we were banging our heads against the wall on. And that week, we were both banging our head against the wall on authentication. It was the number one thing I worked on at Plaid. And so I was particularly frustrated. And then Julianna had just finished a project to rip out Auth0. A project had gone on for six months before she joined, and then it was taking so long that they’d stopped doing it and then later picked it up again. It was like a meme within the company because of how annoying a project it was and how much time it was taking.

Julianna was talking about how frustrating it was internally there, I was talking about how we just had a really bad experience with Auth0 and AWS Cognito at Plaid. And we were just surprised that everything assumed you’re using a password in terms of how the APIs were designed, but also, you didn’t have much flexibility.

And so that was the first time we were both complaining about the same thing, which led it to being the first company idea where I think what we said was: we just presumed there would’ve been a Stripe for authentication in terms of how easy it was to work with an API, to do this rip and replace Julianna was doing or add the password-less features that we were trying to add in the Plaid.

So December 2019 was the coffee. We had left our jobs at Plaid and Very Good Security at end of April, early May, I want to say, to go full-time on this. And we raised our seed round in June of 2020.”

—Reed McGinley-Stempel, co-founder

The founders of Snowflake noticed looming challenges with companies relying on Hadoop:

“In 2012, Thierry Cruanes and I were working at Oracle, and there was not a single day without discussions on how Hadoop [a developer of open-source computer software] was about to make [our work] completely obsolete. I even remember one day interviewing a young engineer who [was] so excited about Hadoop that he didn’t listen to anything we said about Oracle. We realized then that we were missing something.

This made us think a lot about the future [of what we were doing]. Big data was taking over the world, and data warehouses as we knew them were having a really hard time competing. They were—and often still are—rigid, expensive, and difficult to use. At the same time, we were convinced that Hadoop was not a good solution either. Hadoop systems were really too hard to use for most—very inefficient, slow, and missing key features that I would consider must-haves.

This is the point we realized we could [build] a new type of data warehouse system . . . that would master the elasticity of the cloud. [What we built ran] 10 times faster than any other system for the same cost [and freed] users from any management tasks.”

—Benoit Dageville, co-founder, via Yahoo Finance

Ramp’s founders found that credit card companies were solving the wrong problem, through working at Capital One and their previous startup:

“Ramp is a continuation of a lot of things we’ve been working on for a while. I had a company before this called Paribus, which helped people save money on things they were buying online. Within the year, we had about a million customers. Then we got what was a life-changing offer from Capital One to buy the company and went for it. So that was about 2016.

We then spent the next two and a half years there scaling the company. We learned a lot more about how to turn data into savings at scale, and about all the ways that you can use fragments of data processes to automate processes, save people money, and save people time in various ways.

We also ended up in the credit card division within Capital One, where we learned about how credit cards work, how rewards work, and all that. I just remember we talked to customers and asked them, ‘Did you want points, cash back, something different for rewards?’ And what jumped out is people didn’t really want any of that. They wanted to be better-off. And we were just struck by this idea of rewards versus not spending that dollar in that first place.

Pretty quickly we got obsessed with an idea: what if your card was smart enough to help you spend less? It actually might be better for the customer. You might be able to have a better shot at breaking out of the price-based competition.

And fintech was becoming a thing then, where you could actually start these businesses relatively cheaply.

There was only so much we could do inside of Capital One, and we helped what was Capital One Shopping become a thing and grow, and now it’s a big part of what they do, but we also concluded we couldn’t quite do what we were hoping to do inside of the company. So we left and then set out to build Ramp. That’s the story.”

—Eric Glyman, co-founder and CEO

Coda’s Shishir Mehrotra had been thinking about this idea for years:

“Coda started as a series of brainstorms. And at the time, I was reasonably happy at Google. I wasn’t going anywhere. But I had this long list of ideas of just stuff I’d like to see different in the world. This idea is one that’s been on my list for 20-plus years. And in some way or the other, I’ve actually worked on it three different times.

I had a good friend, Alex [eventual Coda co-founder], who was busy starting a company and had decided to pivot to a new idea. He asked me for help brainstorming what he should work on, and we ended up talking about the core ideas behind Coda—that the line between docs and apps is artificial, and that it was time for a new blinking cursor. And in that process, I ended up basically falling in love with the idea again myself. Despite all reasonable indicators of why you shouldn’t start a company, I just couldn’t stop thinking about it. And so I jumped in, and it was kind of funny, when I was talking to my wife: we were driving up to Napa for this wedding, and we’re in the car, and I was like, ‘I think I’m going to do this company with Alex.’ And she says, ‘Yeah, I already knew that.’ And I said, ‘How?’ And she’s like, ‘Because you took every free moment and you’re spending all that time with him on this idea.’”

—Shishir Mehrotra, co-founder and CEO

Gusto’s three founders had secondhand experience with the challenges of running a small business and after ideating, focused on payroll as a great place to start:

“My parents have a clothing store. It’s a small business, and I just grew up there in the store every day after school, going and organizing and selling and answering the phone calls and helping in the store. So I have this kind of small-business experience throughout my family. My grandfather has another store down the street. My aunt had another store. All in the same street in Haifa. So I really grew up around these small businesses, and one thing that’s really, really, really clear is that they don’t have the tools that big companies have in order to be successful. If you think about it, they are the ones who actually need the tools more than anyone else.

So this idea of, what can you do to help this underserved group who need the help and what can you do to level the playing field for small business, is something that was always top of mind for me. Josh, Eddie, and I [co-founders] all share a similar story with small businesses in our families. So when we got together, we wanted to build something.

We kicked around a bunch of ideas for a couple of months. We had this massive whiteboard, and we kind of plotted a lot of different problems that we felt ourselves personally in our lives in different moments and different things, but very quickly we got focused on small businesses and then started talking with people.

We learned that a third of companies make payroll mistakes every year, and they get fines for it every year. That’s insane. The system is incredibly broken, so that’s where the idea came from.”

—Tomer London, co-founder and CPO

For Census, Boris Jabes noticed a big pain point at his previous job and couldn’t stop thinking about it:

“Where the idea came from (eventually): I sold my previous startup (Meldium) to a company called LogMeIn, and I ended up working with a bunch of sales and marketing people there. Working with them was a struggle because they didn’t seem to have the same fountain of usage data that we did on the product and engineering side. That planted a seed in my mind. I thought, ‘There really should just be one version of who is your user, what did they do, and what do we know about them?’ My brain kept coming back to it, and my co-founders found it intriguing as well. But who was it for? In what form? That part was super-vague.

We started to get together in the metaphorical basement, which was my house some days and my co-founder Anton’s house other days. We kept asking, ‘What’s something that is customer data- or CRM-related?’ For a couple of months, we worked on ideas in the domain, even going as far as building the prototype of a CRM for marketplaces.

We realized it was better for us to say, ‘All right, marketplace CRM, let’s do this.’ We did it for two months. We didn’t want to raise on this right away. Instead let’s see if there ‘is a there there.’ We were looking for the combo of something we liked and excited potential users before building in earnest. A sensation that there’s a big problem that I would be willing to spend the next decade of my life pursuing.

Looking back, sitting in a room and trying to come up with a great startup is really bad. We played that exercise for a month, and it’s just bad because we should have been talking to people who had problems. What I realized was all our ideas sounded great, but they were not connected to a specific user pain. For us, writing code, even though it’s not the most efficient use of time, helped us explore ideas best. Maybe we did it in a less efficient way; it forced us to talk to people and build a mental model of the real world.”

—Boris Jabes, co-founder of Census

See you next week!

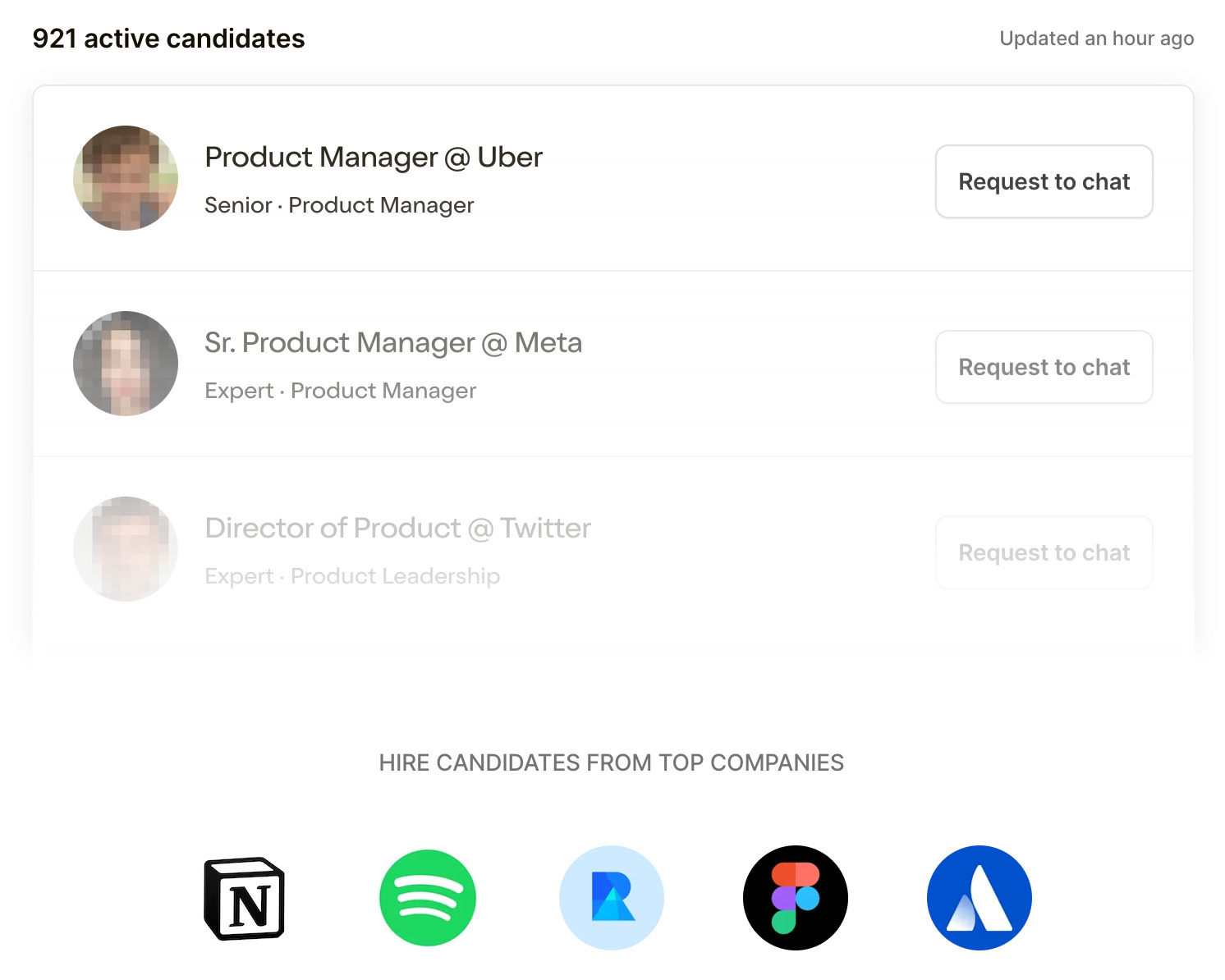

If you’re hiring, join Lenny’s Talent Collective to start getting weekly drops of world-class product and growth people, who are passively open to new opportunities. I hand-review every application, and accept less than 10% of candidates who apply.

If you’re looking for a new gig, apply to join! You’ll get personalized opportunities from hand-selected companies. You can join anonymously, hide yourself from companies, and leave anytime.

Apply to join

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already. There are group discounts, gift options, and referral bonuses available.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋