Public Things - On Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths

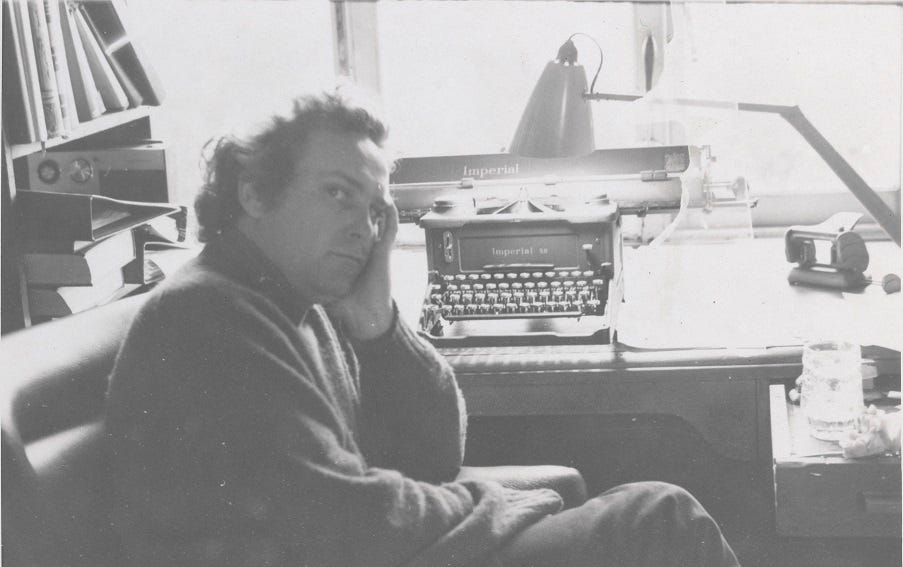

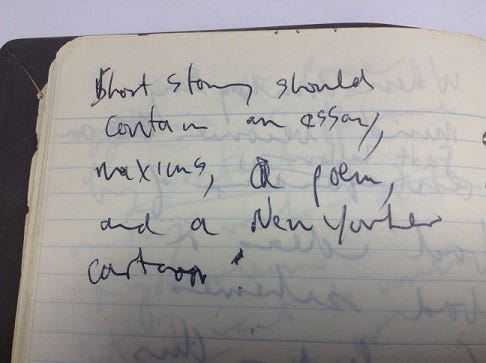

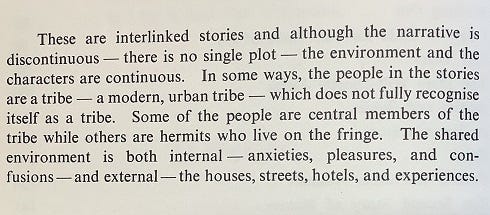

1. With the publication Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths coming out in November, I thought it important to take a moment to reflect on the project, particularly as it is an ongoing concern. This book is the first in a projected two-volume cultural biography of Frank Moorhouse. Volume One covers the period 1938-1974, following Frank’s youth, his long writing apprenticeship, and his breaking into the Australian literary establishment – on his own terms. Volume Two will cover the period 1975-2022, which will include his mature works and the culmination of his lifelong reflections on the foundations of Australian history and culture. I don’t know when the second volume will be ready; I’m still writing it – slowly. I was originally supposed to do the whole project in a single volume, and that was contracted to come out in 2018. My only defence is that had Frank Moorhouse lived a smaller life, I would be writing a smaller book. The real question is: why should you want to read this book? And engage with this ongoing project? When Frank arranged a lunch in 2015 at the Athenian, in Sydney, for me to meet his publisher at Penguin Random House Australia, Meredith Curnow (now my publisher), my pitch was succinct: the main purpose for any literary biography is, first and foremost, to encourage readers to go back and read the subject’s work for themselves. A biography is not a substitute for – but a supplement to – an author’s books. It is to provide context, and various points of entry into Frank’s vast body of work. But it is also to consider how Frank thought about his own life and the historical period through which he lived, and how he came to understand them both through his own writing. A biography is also an argument for why such a body of work is important and worth going back to, to read for the first time or else to read anew; to reassess in light of new archival knowledge. I had to first persuade myself that this was the case with regards Frank’s work, before committing fully to the project. And so in the months before that lunch at the Athenian I read all of Frank’s published books, fiction and non-fiction, in chronological order, from his first book in 1969, Futility and Other Animals, through to what was then his latest publication, 2014’s Australia Under Surveillance. This latter book, a work of non-fiction – which considers questions of privacy, censorship, free expression and the exigencies of state power – clearly looped back and revised lifelong concerns Frank first gathered in his 1980 anthology, Days of Wine and Rage, his reflections on the 1970s. I could already see the outlines of an intellectual trajectory that was worth engaging with further. But it is his literary fiction that marks Frank’s foundational achievement, and that is what he is mostly known for. In this, he is recognised as developing a particular literary form – the discontinuous narrative – although it has not always been appreciated or widely understood. So what is this literary form? 2. The discontinuous narrative form refers to the structure of a book-length work. Over time, it came to refer also to the relationship between various books. Such a book sits somewhere between a traditional collection of short stories and a conventional novel – at times closer to one than the other. The uninitiated should not be too concerned, however. The basic literary unit for Frank remains the short story. It was important for Frank that each short story could be read as a stand-alone work – and many of them were published in magazines and journals with this intention. Each story is immediately accessible to readers, often funny, sometimes sad, always poignant. In a notebook entry from 1974 – after having published by then three books – Frank noted the various senses he was chasing in his own writing: ‘Short story should contain an essay, maxims, a poem, and a New Yorker cartoon.’ In 1967, in his first private statement regarding this developing form Frank said that the discontinuous narrative referred to the way that short stories could be inter-related, with a common cast of characters living in a shared environment. But the stories were only concerned with certain moments or incidents from their lives and interactions with one another. Sometimes the same incident would be shown in different stories from different points of view. The discontinuous narrative form becomes operative when these individual short stories are read together, and when these separate books are read in relation to one another. It is a cumulative effect that activates the imagination in ways that consider the spaces between these stories, the gaps in what we know about these characters – or what we fancy we know – and the precarious footings upon which our judgements of them rest. Such individual points of view are integral to creating the literary effect of the discontinuous narrative form, and the compounding effect of each of these particular stories upon the reader. Each story is usually told – sometimes in first person, usually in third person – but always from an individual perspective of one of the characters in the story. In subsequent stories, other characters from previous stories may appear in this narrative role, at times with their own version of the same incident. But what is essential in appreciating this use of point of view is what is otherwise absent from Frank’s work, and that is any omniscient narrator or overarching continuous narrative structure. Frank rejected what he called a ‘theological unity’ that such a narrator provided. This absence is perhaps the most important characteristic of the discontinuous narrative form, as there is no overarching narrator to adjudicate between these competing versions of what is oftentimes ostensibly the same story. And this sense of uncertainty carries over into those other stories for which we only have one version available to us. As such, there are no fixed endings, and so each story always leaves open a space for further possibilities in the lives of this or that character. The threads of these possibilities are always non-linear: more about each character could always become known – to change or revise our judgement of them – either by going forward to some future point in their life, or else by going back into their past. At times, even by going into the distant past, before the characters was even born. Frank’s first two books, for example, were set contemporaneously with their being written in the 1960s and 1970s. But with his third book, The Electrical Experience (1974), Frank went back to the 1920s and 1930s, exploring the milieu of generations past, and so creating inter-connections, not just between a common cast of characters living in a shared environment, but doing so within an added historical dimension: the relationships between parents and children, and their grandparents. For Frank, this approach to writing fiction proved fecund, with each story he wrote suggesting further stories, with all such stories over-lapping, interlocking, but still retaining the sense of each being but a fragment of an otherwise open and mysterious world, always calling for further exploration. The resonance of each of the short stories in Frank’s books, and the combined resonances between each of his books, provides the reader with a greater role in thinking through and interpreting and making sense of what they are reading. Each of Frank’s books is like a shard of glass within which is refracted the light coming through each of the other books. The lack of any overarching continuous narrative structure, or fixed point of view, encourages this imaginative engagement on behalf of the reader. But with one caveat: whatever sense or meaning we find or impose – it is always provisional. 3. To experience the effect of the discontinuous narrative, and to play a role, as a reader, in activating its form, allowing it to unfold in your imagination, is one of the great joys of in engaging with the work of Frank Moorhouse. This alone would be enough to argue for the value of his work, a justification for a literary biography, and a case for why it is important and worth going back to. For with each story being connected to every other story, each book being both foreground and background to every other book, Frank has produced one of the most innovative and sustained imaginative feats in Australian literary history. And that is something we should celebrate. But there was something else that seized my attention back in 2014-15, when I read through all of Frank’s books, which has kept me interested in this project ever since, and kept me going whenever my energies have flagged, doubts gnawed, or funds depleted, when it would have been easier to give up. I touched on this aspect of his work in the obituary I wrote when Frank passed in 2022. For it was only when I reached Frank’s seventh book of fiction, Forty Seventeen (1988) – when a character, Edith, dies suddenly – that I realised Frank had not had a significant character die in any of his previous books. For the uninitiated, this is not a spoiler, for in Frank’s work such an event does not mark an ending at all. That he avoided this easy literary device for over twenty years was interesting enough, but what made this more remarkable still was that he then spent the next twenty-five years writing three large books – which became known as the Edith Trilogy – which provided this character with a fictional biography worthy of such a death. And it was this realisation – and the question of what this says about Frank Moorhouse as an author and a person, his deep humanity – that finally persuaded me to commit to this project, to attempt a literary biography worthy of such a life. 4. But even as this is what finally persuaded me to commit to this project, it was not what motivated me to begin considering it in the first instance. That started more than a decade earlier, and was the consequence of two coincidences – almost like in a Frank Moorhouse story. I studied literature at university, but it didn’t take long to realise, of course, that the true centre of gravity in the university is not the academy itself, but the library – and that is where I ended up working. This was soon after returning from a stint in England where I worked in a bookshop, and my coming to understand that these are the trenches – bookshops and libraries – where the campaign for literature in our society is won or lost: in the interactions between library staff, booksellers, and readers. And they have at their backs various supporting structures, institutions, and supply chains, the function and purpose of which I wanted to learn more about. And so began a long period of my working variously as a bookseller, library assistant, editor, reviewer, publisher, writer, judge, festival volunteer, grant assessor, gentleman forger, and literary grifter. At the same time I supplemented these practical experiences – as a library user – with an interest in researching the history and broader infrastructure of Australia’s literary culture. This included the history of various institutions – from the Commonwealth Literary Fund through to the Australia Council for the Arts, from the Australian Society of Authors through to the Copyright Agency Ltd – and everything in between: the various government policies, the role of bookshops, libraries, literary festivals, grants and prizes, writers’ centres, and literary magazines. Set against the development of the commercial industry of publishing and various professional associations related to authors, booksellers, publishers, and librarians in Australia. Not to mention the legal and economic structures within which each of these was constituted and reproduced. For what it’s worth, this honed my belief, firstly, that literary culture leavens public culture, and requires as its context a broadly democratic society – that, in practice, a thriving literary culture contributes toward building and maintaining a functioning democracy – and, secondly, that such a literary culture, predicated upon a social practice of reading, presupposes a broadly literate society. The problem is that Australia is deficient in both democracy and literacy, and these are not unrelated to one another; just as both are not unrelated to the low value placed upon our literary culture. What has this got to do with Frank Moorhouse? Everything, it so happens. It is because his name, more than any other, kept cropping up in my research, at different historical pressure points and in various roles: as a copyright litigant, obscenity case defendant, as vice-president and then president of the Australian Society of Authors, chair of the Copyright Council, committee member of the Australian Journalists Association, and so on. For sectors or organisations he was not personally involved with, he at least thought and wrote about them, and had contacts within most of them. And he did so for over 60 years. In this, Frank is not unique. Generations of writers in Australia have done the same, advocating for Australian literature, and trying to build an infrastructure to sustain it. The reports, studies, and histories I based my own research on was itself written by generations of writers, academics, and arts workers. All of whom have at one point or another been involved behind the scenes, building the sets against which others could perform. They have their exits and their entrances. For more than any other Western, industrial nation, it is a condition of Australia’s literary culture that writers have to continually create the space within which they can write, in conditions at once precarious and ephemeral. Those stubborn conditions are themselves the outcome of past decisions and current inertia. Not enough is made of this, although everybody knows it. And this leads to the first coincidence. In 2006 I was doing my initial attempt at piecing together some early research – making a mud map of Australian literature, broadly construed to also include the infrastructure within which such literature is made possible – when there appeared serendipitously in the Weekend Australian, over three weeks, a three-part series that was doing the very same task – only better. The author was Frank Moorhouse. That was my excuse to make my first contact with Frank – although I didn’t meet him in person for another six years – but this set the main topic of conversation and argument which continued for the rest of his life – and which I am continuing now in writing his biography. What I didn’t appreciate at the time – even though his name kept cropping up in my research – but only learned after accessing his archive, was the breadth and depth of his engagement, and his belief that literary culture leavens public culture. Such questions occupied an inordinate amount of Frank’s thinking, and arguably more than any other writer in Australia Frank integrated this into his practice of writing. Where others did much in select fields, or dipped in now and again to face an imminent threat, Frank seemed to be consistently involved in more fields and for longer; always trying to get an overview of the whole situation, the better to plot a course within. Many know about Frank’s landmark copyright case in the 1970s – part of the background that later established the Copyright Agency Ltd. But most don’t know about the court case in the late 1970s – which Frank launched against his publisher – that established an author’s legal ownership of their own manuscripts, even after they are submitted to a publisher – part of the background to authors being able to control and profit from selling their own manuscripts to libraries and archives, or by choosing not to do so. Or else there is the initiative Frank dreamed up from a hospital bed in the early 1980s, which he then advocated for and established – Australian National Parks hosting residencies to support arguably the first environmental writing fellowships in Australia. Or else there is the legal brief Frank initiated in the 1990s that urged the executors of the Miles Franklin Award to broaden their definition of ‘Australian Life’ – thus making eligibility to Australia’s premier literary award more open and inclusive. And so on, and so on. Even this three-part series from the Weekend Australian in 2006, which I mentioned above, was based on more than what the public otherwise aware. And it was not until I went into Frank’s archive that I discovered it was based upon a 65,000 word (unpublished) report on the state of writing in Australia he had completed the previous year. It would take a book to recount everything Frank accomplished; and a two-volume book to do it justice. But for each initiative Frank was able to implement, there are just as many he was unable to get up and running – but those ideas and strategies, dormant among his papers, are still potentially operative. Frank’s ideas, I argue, could still make an impact. 5. This leads to the second coincidence, which proved the occasion for our finally meeting in person, and dining out in earnest. In 2012 I launched a digital journal called the Review of Australian Fiction, in which we published two short stories every two weeks. The first story in each issue was from an established Australian author, and the second story was from an emerging Australian author. We chose the established author, but we asked them to choose an emerging author to be paired with. We wanted to make public the otherwise hidden network of mentoring that occurs behind the scenes in Australian literature – one of the necessary strategies for survival. Over the next six years we published 288 short stories, with 50% of sales going to the authors in the form of royalties. The rest covered operations and copyediting. My partner in this venture, Phil Crowley (as manager), and I (as editor), earned nothing, but accrued a substantial debt. One of the sources of inspiration for the project was an innovative publication Frank launched (along with Michael Wilding and Carmel Kelly) in the early 1970s called Tabloid Story. When I told Frank about our journal he offered us his (still) unpublished erotic fable, Sønny, for the first issue. That would have been a fantastic way to launch a new journal of Australian fiction, but unfortunately circumstances conspired against us, and this ended up not happening – although we later ran an excerpt from Sønny in a later issue. At the same time the Review was being prepared for launch, I was in the process of moving from Queensland to Tasmania. All the correspondence I had previously had with Frank – including arrangements for the Review – were done from Queensland. One of the final things I did in my last day at work in Queensland was print out a short story I had written and posted it into the Josephine Ulrick Literature Prize. My new contact details in Tasmania were included. I had never told Frank that I wrote fiction – it turns out I am just as good at compartmentalising my life as Frank was at compartmentalising his – and I never knew that Frank was one of the judges of the Josephine Ulrick Literature Prize that year. The judging was blind, and so it wasn’t until after my story was chosen as the winner that Frank learned the name of the author. But even then – because the contact address was from Tasmania – he wasn’t sure if it was the same person he had been previously corresponding with. It wasn’t until we were brought together on the Gold Coast for the awards ceremony that we finally met in person, our first exchange being about putting all the pieces together. I signed the $20,000 prize money over to the Review of Australian Fiction, a recklessness that impressed Frank enough that he began having lunches and dinners with me whenever I happened to be in Sydney. Soon after, I started going to Sydney purposely to have these lunches and dinners, to continue our conversation and argument about Australia’s literary culture. The tenor of these conversations often slipped into the same pattern as that initial coincidence with the Weekend Australian series in 2006. Time and again, I would have an idea, and when I tested it on Frank I would quickly discover he had the same idea first, but probably better thought through, better articulated. And oftentimes he had the idea before I was even born. But what I later learned, after accessing his archives, and reading over his earlier notes and articles published in now forgotten newspapers and magazines, was that Frank had also forgotten more than I have ever known. The few occasions I shared an idea with him, which he treated as though something new and exciting, I would later find the same idea tucked away on an index card or in a notebook or an article from the 1960s or 1970s or 1980s. And so this is what motivated me to begin delving into his archives. Initially, it was not with the intention of writing a biography, but solely to satisfy my own curiosity, to search for ideas which could become the topic of the next conversation with Frank, the next argument. And when our conversation finally turned to the prospect of my writing a biography it was, for me at least, not so much as an end in itself, to put yet another book out into the world, to be largely ignored, but as an excuse to legitimately spend more time thinking and arguing with Frank, whether in person, or with him as his archives and published works presented pieces of himself, at various ages, and in various situations, to me. And so, in this way, I became his accidental biographer. 6. What I came to appreciate is that Frank is a literary intellectual, not only in the sense that he thought deeply about literature and its role in society, but that he used his literary imagination to engage with the social, political, and cultural world he lived in. He read deeply and broadly in fields of sociology, anthropology, economics, history, political theory – and much besides. But he also had decades of practical experience – he started writing and publishing in the 1950s, his final books were released in the 2010s – and he constantly used his practical experience to measure the value of his theoretical thinking, and he used what he found valuable in that thinking to expand the possibilities, to test the limits, of his practical experience. And this informed also his literary work. It is a style of thinking, grounded in the imagination, which is best articulated in the discontinuous narrative form. For this narrative form reflects Frank’s own approach to life. He did not consider there to be an underlying harmony to existence or overarching plan; there is no fixed pattern. He was interested in exploring – in his life, in his fiction – what he called the non-causal nature of social events, and the role that chance, misadventure, and the collisions that occurred between individual behaviours (usually non-rational) and the choices such individuals make – both in creating such events in the first instance and then in the way we try to impose sense onto them, through telling ourselves stories – whether they be historical, ideological, religious, or philosophical. He was a literary intellectual, however, because he did not subordinate himself to such grand narratives, and their omniscient narrators, proffering fixed and false meanings. Fiction can be beyond ideology,’ he noted in 1974. ‘The process produces a shape of reality or self which for a while (or permanently) clarifies our life & allows us to “cut through” illusions, ideologies…’ And so his focus, his satire, was often on the artificial props upon which such stories rested. The private customs, social conventions, and public laws and constitutions within which such stories are created – and the rituals of behaviour and habits of mind individuals foster in order to maintain each. His example, both in his fiction, in his non-fiction – in his advocacy, in his life – was that because such narratives were discontinuous, then new habits of mind could always be developed, and new rituals of behaviour could always be enacted, replacing – or at least, revising – existing customs, conventions, laws, and constitutions. We made our public culture, and so we can make in anew. 7. For me, biography is itself a literary form. Writing biography is an act of imagination, first and foremost; just as reading one requires the engagement of the readers’ imagination. It is precisely because of this, however, that biography writing is so dependent on accuracy, precision, context, and a critical fidelity to the archive – as this is the only material we have available to us in order to select and arrange in a narrative form, in order to build up a moving image of a particular life. Just as the infrastructure of Australia’s literary culture – the bookshops and libraries, and supporting structures, institutions, and supply chains, for each – is the necessary material ground upon which an Australian literature can develop. A biography is an argument, made to persuade the reader to consider the subject from a particular perspective. And as much as possible that perspective should be consistent with and proportionate to that underlying material. But it is not absolute, and can never be exhausted. It is for this reason that a biography can never be definitive, but is always (dare I say?) discontinuous, always open to retelling and reinterpretation. I’ve tried to incorporate that openness and discontinuity into the first volume of this book; as well as in the second volume, which I am still writing. This project is about opening the imagination, and keeping it open, rather than foreclosing it. It is this aspect of Frank’s life and work that initially motivated me to engage more deeply with it; just as reading his literary fiction persuaded me to finally commit to this project. My pitch to you is to read Frank’s books for yourself. But the ultimate challenge – the challenge Frank set himself, and whose life and work dares others to accept – is to engage afresh with currents and eddies of Australian culture. This is what should keep us coming back, again and again, to reading and rereading Frank’s books, and to always keep his life and work an open and vital question. You're currently a free subscriber to Public Things Newsletter. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Older messages

Invite your friends to read Public Things Newsletter

Thursday, June 22, 2023

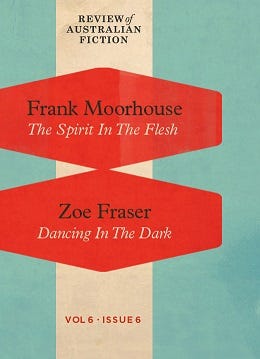

Thank you for reading Public Things Newsletter — your support allows me to keep doing this work. If you enjoy Public Things Newsletter, it would mean the world to me if you invited friends to subscribe

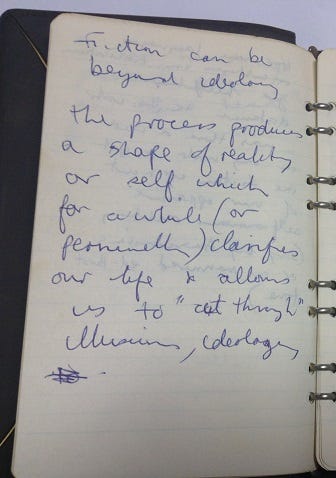

Northrop Frye’s Four Levels of Literary Meaning

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

Or, the nuts and bolts of reading

‘He waxes desperate with imagination’

Monday, October 17, 2022

Or, re-reading “Hamlet” with Margreta de Grazia and Luiz Costa Lima

A Substacker Reads Luiz Costa Lima in Australia and Bursts into Tears (with apologies to László F. Földényi)

Monday, October 3, 2022

On mimesis, fiction, and the control of the imaginary

On Edgar Allan Poe and the economics of literary theft

Monday, September 12, 2022

Otherwise known as publishing

You Might Also Like

Kendall Jenner's Sheer Oscars After-Party Gown Stole The Night

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

A perfect risqué fashion moment. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 3.3.2025 Now that award show season has come to an end, it's time to look back at the red carpet trends, especially from last

The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because it Contains an ED Drug

Monday, March 3, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It Contains an ED Drug The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It

10 Ways You're Damaging Your House Without Realizing It

Monday, March 3, 2025

Lenovo Is Showing off Quirky Laptop Prototypes. Don't cause trouble for yourself. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY 10 Ways You're Damaging Your

There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood

Monday, March 3, 2025

Today in style, self, culture, and power. The Cut March 3, 2025 ENCOUNTER There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood A Sex Education fan favorite, she's now breaking into Hollywood on The White Lotus. Get

Kylie's Bedazzled Bra, Doja Cat's Diamond Naked Dress, & Other Oscars Looks

Monday, March 3, 2025

Plus, meet the women choosing petty revenge, your daily horoscope, and more. Mar. 3, 2025 Bustle Daily Rise Above? These Proudly Petty Women Would Rather Fight Back PAYBACK Rise Above? These Proudly

The World’s 50 Best Restaurants is launching a new list

Monday, March 3, 2025

A gunman opened fire into an NYC bar

Solidarity Or Generational Theft?

Monday, March 3, 2025

How should housing folks think about helping seniors stay in their communities? ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Banality of Elon Musk

Monday, March 3, 2025

Or, the world we get when we reward thoughtlessness ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

“In life I’m no longer capable of love,” by Diane Seuss

Monday, March 3, 2025

of that old feeling of being / in love, such a rusty / feeling, ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Your dishwasher isn’t a magician

Monday, March 3, 2025

— Check out what we Skimm'd for you today March 3, 2025 Subscribe Read in browser Together with brad's deals But first: 10 Amazon Prime benefits you may not know about Update location or View