A24: The Rise of a Cultural Conglomerate

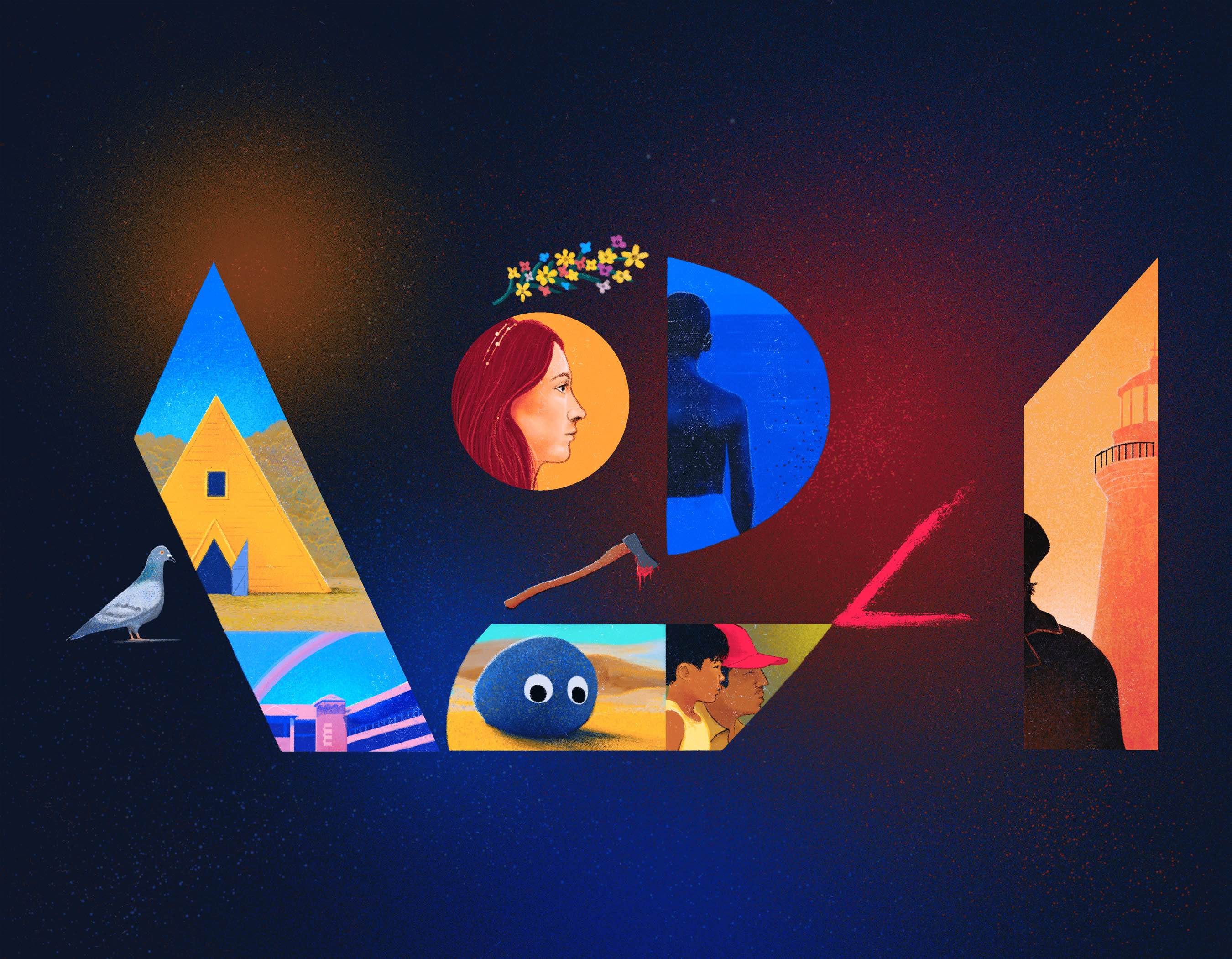

A24: The Rise of a Cultural ConglomerateThe indie studio is behind some of Hollywood’s biggest hits and critical darlings. It has designs on becoming media’s answer to LVMH.Friends, If you’ve been to the movies in the last decade, there’s a good chance you’ve seen an A24 picture. In all likelihood, you’ve seen many. Since its founding in 2012, few companies have had as oversized an impact on the zeitgeist. The New York-based firm is behind box office wins, cultural phenomena, and your favorite indie flick you wish more people would watch. Moonlight, Lady Bird, Hereditary, Uncut Gems, Midsommar – A24 has had its hands on all of them. And that’s without mentioning its biggest hit: Everything Everywhere All at Once. That mind-spinning multiverse picked up 7 Oscars earlier this year, including the Best Picture Award. While A24 is no stranger to the red carpet, it was another affirmation of the studio’s creator-centric model. Indeed, the company behind so many films we’ve enjoyed is arguably as fascinating as the projects it produces. In an industry dominated by slow-moving heavyweights, A24 is the nimble disruptor, bringing a fresh, tech-forward playbook to the world of film. It also has ambitions to expand beyond its current ken. Initiatives in TV, music, publishing, consumer goods, and physical experiences hint at a desire to establish a 21st-century media conglomerate – but one with the commitment to craft and creator-centricity of a luxury house like LVMH. It is, in short, not only a maker of great stories but a great story in and of itself. An ask: If you liked this piece, I’d be grateful if you’d consider tapping the ❤️ in the header above. This helps us understand which pieces you like most, and what we should do more of. Thank you! Brought to you by MercuryEven with big ambitions, only a small percentage of startups make it. Mercury Raise is here to change that. Introducing the comprehensive founder success platform built to remove roadblocks at every step of the startup journey. Looking to fundraise? Get your pitch in front of hundreds of the right investors with Investor Connect. Craving the company of people who get it? Join our Slack community of vetted founders for access to networking opportunities, moderated discussions, curated news, and AI-powered intros. Plus, participate in AMAs with renowned investors and industry experts. Searching for answers to the questions you can’t Google? Step into Expert Sessions, the virtual offices of top investors, founders, and operators for personalized guidance and direction-setting insights. With Mercury Raise, you don’t have to go it alone. Actionable insightsIf you only have a few minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders should know about A24.

Stranded on a beach, a suicidal man finds a washed-up corpse (Daniel Radcliffe). Five minutes later, the man is riding the corpse like a jet ski, powered by the dead fellow’s flatulence. Swiss Army Man, the debut of directing duo Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, led to a series of walkouts at Sundance Film Festival, and, initially, only one underwhelming distribution offer from Netflix. Then A24 appeared. According to Scheinert, A24 was so keen on the film that the firm’s Head of Acquisitions told the directors “he would jump out of a window” if they picked a different partner. While major studios were scared off by a movie about a farting corpse (played by Harry Potter), A24 knew that would be exactly what their core audience – terminally online, culturally-adventurous millennials – would love to watch. Six years later, the same directing duo, known as “the Daniels,” released a film about a middle-aged, Chinese-American woman who runs a laundromat. On a budget of $25 million, Everything Everywhere All At Once surpassed $140 million at the box office, scooping up seven Academy Awards in the process. On its surface, Everything Everywhere seems antithetical to traditional Oscar fare: it’s a Marvelian-multiverse-sci-fi-comedy, starring an older Asian woman, with subplots involving animate rocks, an enchanted everything bagel, and hot-dog fingers. The success of the film is a testament to the creators and cast. But it’s also a reflection of the strategy of the studio behind it. As a former studio executive remarked, “You get to an Everything Everywhere All at Once because A24 nurtured the Daniels.” Since its founding in 2012, the New York-based firm has taken a contrarian path to cinematic success. While Hollywood’s major studios have spent the last decade pumping out superhero vehicles, A24 has embraced creative risk. Rather than looking to underwrite safe bets, founders David Fenkel and Daniel Katz look for true auteurs – then back them to the hilt. From one vantage, it’s an almost venture-like search for outliers; from another, it resembles LVMH’s designer-centric approach. As at Bernard Arnault’s luxury conglomerate, for A24, the artist is sovereign. So far, it’s worked. Alongside the Daniels, A24 has backed the visionaries behind hits like Uncut Gems, Hereditary, Lady Bird, Midsommar, and Ex Machina. As well as delivering strong returns – and propelling the shop to a $2.5 billion valuation – A24’s filmography has earned critical respect and accumulated rare cultural power. It has become a brand unto itself, celebrated for its weirdness, distinctiveness, and craft. Though the titles mentioned differ in subject matter and style, they possess some shared DNA, an A24 allele, difficult to articulate but there nonetheless. That singular essence has spawned an unusual fandom: moviegoers are not only besotted with individual releases but the studio itself. Consumer devotion of this kind is unusual for those who stand behind the curtain. Though many may love the stories they tell, few would consider themselves Paramount obsessives, Columbia Pictures devotees, MGM ultras. Like Disney before it, A24 is an exception to this rule. And like the House of Mouse, it has started extending its consumer relationship beyond the screen. Over the past few years, A24 has pushed the borders of its empire, moving into TV, music, publishing, physical experiences, and even cosmetics. It takes little imagination to see the contours A24 is following, to find a redux of Walt’s strategy designed for the 21st century. A24’s modernity, especially from a tactical perspective, is an underrated aspect of its story. Yes, its success stems from its differentiated taste and unusual support for artists. But it is also a technology story. Social media smarts underpinned the firm’s rise, allowing it to acquire attention much more cost-effectively than its more backward-minded peers. So did its understanding of internet culture, memes, and viral mechanics. Over the past decade, no studio has more efficiently inserted itself into the online zeitgeist, seasoning our feeds with satanic goats and Oscar Isaac dance sequences. A24’s tech-savvy may make it better placed to weather the existential seiche sweeping across Hollywood. Tensions between talent and the big studios reached a boiling point this summer, resulting in an industry-wide strike. Among these organizations’ demands is an appeal for safeguards around the use of artificial intelligence. Concerns around the misuse of actors’ likenesses are arriving not a moment too late as new models make creation and emulation increasingly life-like. It puts A24 in an interesting position: the champion of talent at a time when their value is in flux. Only time will tell if A24 is a beneficiary or casualty of such a seismic disruption. To understand A24’s origins, rise, playbook, and future, we conducted deep research and interviewed several senior sources at the studio. Origins: The making of A24Autostrada 24 (A24) is a 103-mile highway linking Rome to Teramo. It’s largely the domain of Roman commuters and the occasional petrified tourist driver. It also happens to be where, in 2012, Daniel Katz came up with the idea for a company that would change the entertainment industry. There was a haze over The Eternal City as Katz approached the outskirts of Rome, but his mind was clear. The Guggenheim Partners investor had always dreamt of starting a company – perhaps in the film industry, which he specialized in financing – but a fear of failure had halted his ambitions. Katz’s concerns were far from irrational: just 3.4% of independent films in the US make a profit and 90% never get a theatrical deal. Few would have been as aware of such unfavorable odds. But as Katz motored down the autostrada, taking in the Italian air, he experienced an entrepreneurial epiphany:

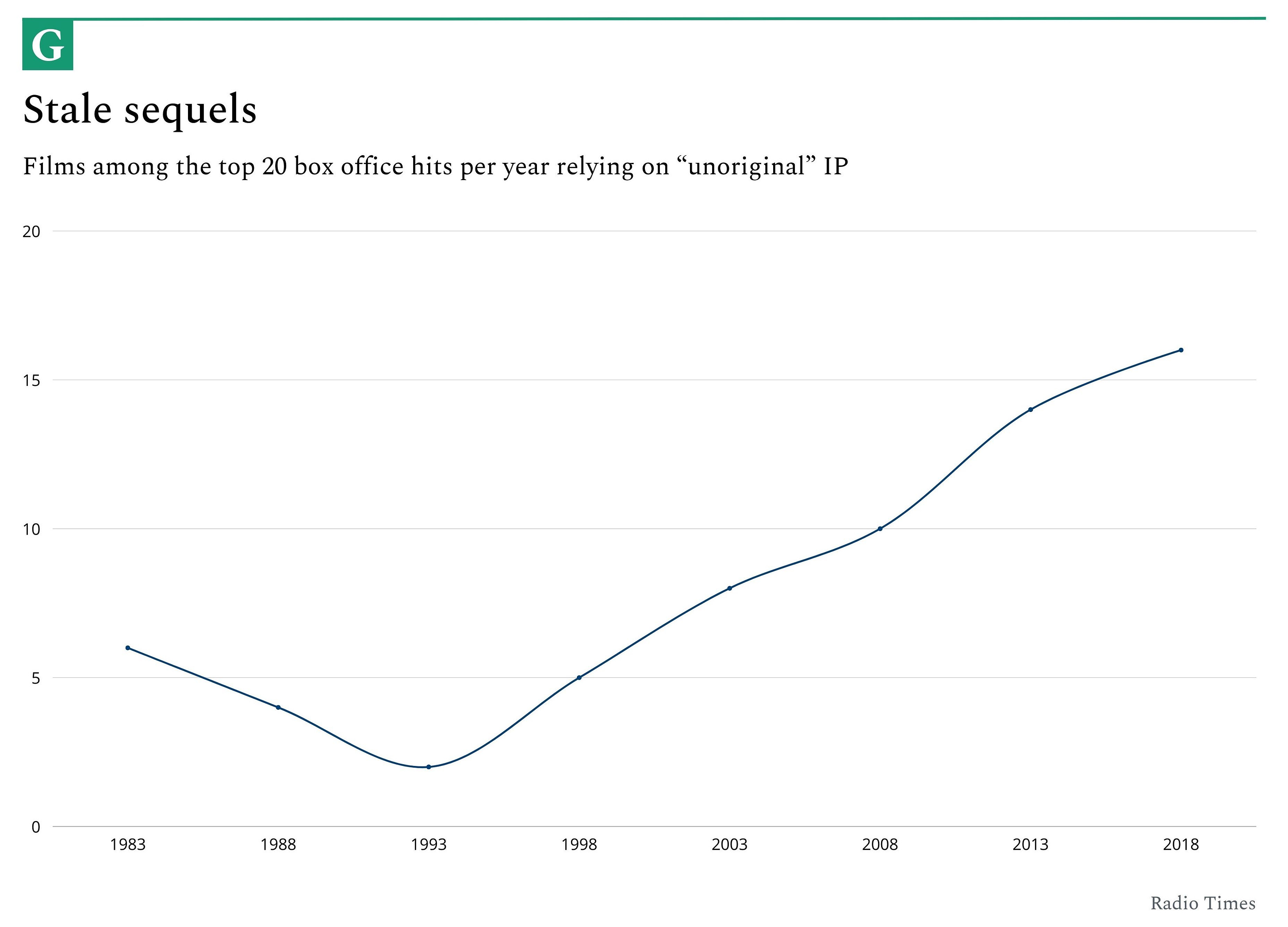

It was only fitting that Katz would choose to name his company after the site of his inspiration. An insipid status quoThough admirable, Katz’s conviction and professional bonafides were no guarantee of success. If the financier shared his grand vision over a plate of cacio e pepe that evening, one could forgive any skepticism on the part of his traveling companions. After all, independent film is a graveyard of plucky, ambitious companies founded by capable people. It’s cost-intensive to start, and difficult to reap rewards. The fortunate ones struggle on until bought by one of the major studios. The late Jake Eberts – producer of classics like Chariots of Fire and Driving Miss Daisy – summarized the nonexistent returns indie films typically yielded, telling private equity investors they “might as well throw their money down a rat hole.” To avoid lining the rodents’ residences, Katz teamed up with two other industry experts: David Fenkel and John Hodges. Both had led distinguished careers in film. In 2008, Fenkel had co-founded Oscilloscope Laboratories, the company behind We Need to Talk About Kevin, and an adaptation of Wuthering Heights. Hodges, meanwhile, had led development and production at Big Beach Films. Among the firm’s successes was 2006’s Little Miss Sunshine, a surprise indie smash that won two Academy Awards and grossed more than $100 million from an $8 million budget. Though experience was far from a guarantee of success, A24’s founding trio combined a strong blend of financial, operational, and acquisition experience. Beyond their expertise, Katz, Fenkel, and Hodges shared a similar view on the state of the movie industry – one warped by the dynamics of the large movie studios. There’s a saying in venture capital: “your size is your strategy.” The idea is that the amount of money you manage determines the playbook you can run. A bespoke fund with $10 million under management can operate a very different strategy to Coatue with its colossal stack – and vice-versa. For the smaller shop, an investment of $1 million that appreciates 10x makes a huge difference, returning the fund. For a megafund, it would barely make a dent. To deliver a meaningful return, these larger vehicles have to put more money to work and swing for bigger returns. Similar dynamics play out in the film industry. The big studios preside over large war chests that must be deployed. Because of their size, it makes little strategic sense for players like Paramount, Columbia, or Warner Bros. to invest $5 million into a small, speculative project that might pull in $30 million. This is why they focus their efforts on high-budget vehicles that have the potential to gross billions globally. To minimize the risk of this outlay, major studios have gravitated towards safe bets like sequels and reboots. Why bet on an unproven indie concept when you can disgorge another iteration of Fast and Furious? The impact these incentives have had on film production is clear. Over the past thirty years, prequels, sequels, reboots, and spin-offs have come to dominate box office charts. The direction of travel was readily apparent by 2012. Nine years earlier, in 1993, just two of the twenty top-grossing films were derived from “unoriginal” IP. By 2008, that figure had climbed to ten; by 2013, fourteen. A24’s founders had noticed this decay. Rather than bemoaning it, however, they spotted an opening. Just because big studios didn’t want to make opinionated indie films anymore didn’t mean that audiences didn’t want to watch them. On the contrary, amidst an increasingly homogeneous cultural landscape, projects with a genuine point of view could have an outsized impact. “Films didn’t seem as exciting to us as when we started our careers,” Katz noted. “And that signaled an opportunity.” The disruptive distributorFor such a colorful industry, much of the nomenclature Hollywood uses can be rather drab. What role in the creative process does the producer play? What exactly does a distributor do? To those with an understanding of the industry, such questions are as basic as asking what part a product manager or UX designer plays at a startup, but for those uninitiated, it's worth distinguishing. In simple terms, producers bring a creative project to life. They are manager and orchestrator, coordinating between stakeholders from pre-production through to a film’s release. In addition to being the party that finds a script and secures financing, they help hire behind-the-camera talent, keep the shooting process on the rails, play a role in editing, and position the project to become a box office hit. It’s not uncommon for multiple production companies to collaborate on a given project. Distributors play a much more limited role. They arrive once a film is finished and work to release it as successfully as possible. That involves striking deals with theater chains, implementing a marketing strategy, and negotiating overseas circulation. Though a distributor’s job is fundamentally consumer-facing – their goal is to sell tickets – they tend to operate subtly. They are, in a sense, the infrastructure software of the film world. They’re fundamental, but if they’re doing their job right, you’ll barely notice them. Indeed, many cinemagoers scarcely realize there’s a whole industry that just buys finished films and puts together all the trailers, posters, and, occasionally, life-size Barbie boxes. A24 began its life as a distributor. Its team frequented film festivals, acquired the rights to promising pictures, and set about marketing them. It was a pragmatic starting point, grounded in the reality of the firm’s size. Rather than risk vast sums taking a project from script to screen, A24 concentrated its capital on finished projects that at least had a shot of delivering a return. “When we started, it was last money in, first money out,” one executive noted. If that was A24’s sole strategy, they would not have become the innovative company they are today. In addition to sitting in a de-risked part of the stack, A24 made four critical decisions that became a core part of the firm’s strategy:

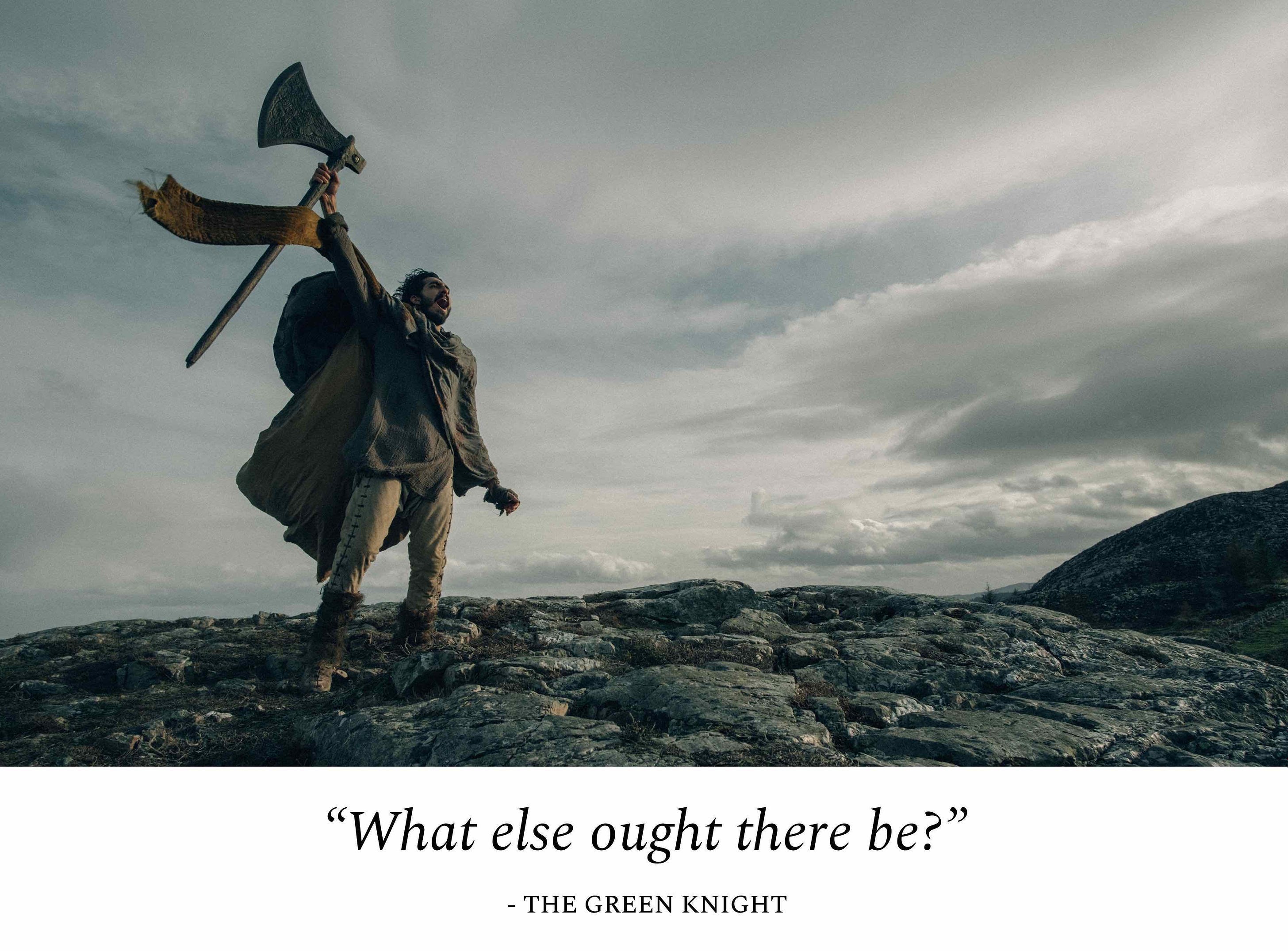

A24’s differentiated strategy starts with its distinctive culture. In many respects, it’s a firm inspired by Silicon Valley rather than Hollywood. “We’ve been very influenced by how technology companies think about the world,” one executive remarked. Another affirmed that position, referring to A24 as “more akin to a tech company than a classic studio.” Employees receive equity in the business, and the company operates with a flat organizational structure. Indeed, the firm’s headquarters in New York has been specifically designed to accommodate this approach. “No one has an office; everyone sits out on an open-plan floor,” one source remarked. This atmosphere is designed to encourage team members to share ideas, regardless of their position in the organization. Above all, A24’s management seems to want to provide the freedom to ideate and experiment. “I felt like there was a huge opportunity to create something where the talented people could be talented,” Katz said. That is more than just talk – A24 has purchased projects recommended by employees outside its core acquisition team. While ownership, openness, and a meritocracy of ideas are standard in the startup world, they are aberrations in the more rigid, old-fashioned entertainment business. A24’s culture may be progressive, but its financial strategy is on the conservative side. When it comes to investing in a project, A24 makes purposefully small investments. It does so to spread the risk around and ensure that a couple of bad bets don’t jeopardize the viability of the enterprise itself. This was particularly important in the firm’s early days when it operated with a more constrained budget, though it remains true today. “We specifically size films so that they’re not massive swings,” one executive remarked. Such fiscal prudence gave A24 the confidence to take risks elsewhere – namely, on the creative side. From the very beginning, Fenkel, Katz, and Hodges made the decision to seek outlier auteurs, those with bold, original visions. Their thesis was that gifted creators with a distinct point of view would appeal to younger audiences seeking an antidote to Hollywood’s stale sequel machine. While other distributors and producers often tried to subdue directors’ stranger creative instincts, A24 took the opposite approach, leaning in. “Every project they do is ride or die,” one streaming executive said of A24. “And they make creators feel that way. It’s their superpower.” Beginning life as a no-name upstart, A24 took particular pains to emphasize its creator-centricity. In 2012, for example, the distribution rights for Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers became available. It was a pitch made for Katz: A hazy fever dream set in a swampy demi-monde, directed by one of the most interesting experimental filmmakers alive. He wasn’t about to let it get away. To woo the film’s producers, Katz’s team sprang into action. Head of Acquisitions Noah Sacco recalled the episode. “I woke up one morning to an email from Daniel that was sent at three in the morning: “Can you go to Pittsburgh?” I come into the office, and there are interns running around like in some crazy factory.” An ordinary gift basket wouldn't suffice for the team behind Spring Breakers. To stand out from the chasing pack, Katz had tasked his staff to commission a custom set of gun-shaped glass bongs, engraved with the film’s logo. If anything showed A24’s understanding of Korine’s world, surely, this was it. The bongs did the trick. Spring Breakers became A24’s first big win, turning a $5 million budget into $32 million at the box office. In addition to validating demand for the types of films A24 wanted to showcase, Spring Breakers showcased the startup’s distribution chops. In particular, it illustrated the fruits of embracing the internet as a marketing channel. In 2012, few studios or distributors had learned how to leverage the web’s disruptive power. Incumbents had yet to truly understand social media dynamics, memetic content, and online culture. In their defense, although the internet and social media were far from novel by then, they had yet to become as ubiquitous as they are today. It had only been five years since Steve Jobs debuted the iPhone, bringing handheld internet access to the mainstream; the same year that A24 launched, Instagram sold to Facebook for $1 billion. As geriatric studios tried to figure out how to connect to the WiFi, A24 made a virtue of its youth. The early 2010s were an era of Manifest Destiny in social media marketing, a time before advertising dollars had flooded in and when content was shifting from text to image-based. Between your uncle’s daily bible quote and a friend’s relationship update lay acres of barren news feeds, waiting to be claimed. A24 moved to colonize all of them, setting up accounts on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tumblr, Snapchat, and Pinterest. The firm reaped the benefits of low competition and seems to have continued to do so. According to one executive, A24’s marketing spend is “many multiples” better than other studios. Its promotion of Spring Breakers demonstrated the firm’s ability to titillate, court the right amount of controversy, and capture attention online. Since the film starred Disney Channel favorites Vannessa Hudgens and Selena Gomez, much of A24’s marketing materials played up the fallen woman narrative; innocence, corrupted. To stir up excitement about James Franco’s against-type performance as a cornrowed hustler, A24 published a rendition of the Last Supper, with Franco’s character as Jesus. It quickly went viral on Facebook. In the years that followed, A24 kept pushing boundaries in online marketing. In 2015, the firm purchased the distribution rights to Alex Garland’s sci-fi drama Ex Machina. The film explores the emergence of artificial general intelligence, represented in the figure of Ava, a humanoid robot portrayed by Alicia Vikander. To build buzz around the film, A24 created a Tinder bot in Ava’s image, releasing it at South by Southwest. It was a clever stunt, earning a score of articles from mainstream publications. It helped deliver another significant win – both commercially and critically. Ex Machina grossed $36 million at the box office from a $15 million budget. It earned widespread acclaim, receiving Oscar nominations in the “Original Screenplay” and “Visual Effects” categories, winning in the latter. Writer and director Alex Garland did not mince words when discussing A24’s impact. “I would say that if Ex Machina had been distributed by a big studio, the film would not have been remotely as well received or successful as it was.” In just three years, A24 had built a promising financial track record and even landed an Academy Award. Within two more, it would have a Best Picture winner on its hands. Puzzler

A more challenging riddle meant a smaller winner’s circle. Kudos to Michael O and Ryan A for this rarest of medals. Our last puzzler:

The answer? A volcano. Until next time, Mario You're currently a free subscriber to The Generalist. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Older messages

Modern Meditations: Rebecca Kaden (Union Square Ventures)

Sunday, September 17, 2023

The Union Square Ventures managing partner on stories, ancient structures, and technological salvation.

Life in a Kingdom of Dangerous Magic

Sunday, September 10, 2023

Or, why regulating artificial intelligence is so difficult.

Introducing our newest writer

Thursday, August 31, 2023

Welcoming a fresh voice to The Generalist and what that means for readers.

Modern Meditations: Claire Hughes Johnson

Sunday, August 20, 2023

The Stripe executive on leadership, linguistics, and literature.

We'd love to learn more about you.

Tuesday, August 15, 2023

If you have three minutes to spare, we'd be grateful if you'd take this quick survey.

You Might Also Like

🚀 Ready to scale? Apply now for the TinySeed SaaS Accelerator

Friday, February 14, 2025

What could $120K+ in funding do for your business?

📂 How to find a technical cofounder

Friday, February 14, 2025

If you're a marketer looking to become a founder, this newsletter is for you. Starting a startup alone is hard. Very hard. Even as someone who learned to code, I still believe that the

AI Impact Curves

Friday, February 14, 2025

Tomasz Tunguz Venture Capitalist If you were forwarded this newsletter, and you'd like to receive it in the future, subscribe here. AI Impact Curves What is the impact of AI across different

15 Silicon Valley Startups Raised $302 Million - Week of February 10, 2025

Friday, February 14, 2025

💕 AI's Power Couple 💰 How Stablecoins Could Drive the Dollar 🚚 USPS Halts China Inbound Packages for 12 Hours 💲 No One Knows How to Price AI Tools 💰 Blackrock & G42 on Financing AI

The Rewrite and Hybrid Favoritism 🤫

Friday, February 14, 2025

Dogs, Yay. Humans, Nay͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

🦄 AI product creation marketplace

Friday, February 14, 2025

Arcade is an AI-powered platform and marketplace that lets you design and create custom products, like jewelry.

Crazy week

Friday, February 14, 2025

Crazy week. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

join me: 6 trends shaping the AI landscape in 2025

Friday, February 14, 2025

this is tomorrow Hi there, Isabelle here, Senior Editor & Analyst at CB Insights. Tomorrow, I'll be breaking down the biggest shifts in AI – from the M&A surge to the deals fueling the

Six Startups to Watch

Friday, February 14, 2025

AI wrappers, DNA sequencing, fintech super-apps, and more. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

How Will AI-Native Games Work? Well, Now We Know.

Friday, February 14, 2025

A Deep Dive Into Simcluster ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏