Astral Codex Ten - Dictator Book Club: Chavez

[previously in series: Erdogan, Modi, Orban, Xi, Putin] I. All dictators get their start by discovering some loophole in the democratic process. Xi realized that control of corruption investigations let him imprison anyone he wanted. Erdogan realized that EU accession talks provided the perfect cover to retool Turkish institutions in his own image. Hugo Chavez realized that there’s no technical limit on how often you can invoke the emergency broadcast system. You can do it every day! The “emergency” can be that you had a cool new thought about the true meaning of socialism. Or that you’re opening a new hospital and it makes a good photo op. Or that opposition media is saying something mean about you, and you’d like to prevent anyone from watching that particular channel (which is conveniently bound by law to air emergency broadcasts whenever they occur). This might not be the only reason or even the main reason Hugo Chavez ended up as dictator. But it’s a very representative reason. If Putin is basically a spook and Modi is basically an ascetic, Hugo Chavez was basically a showman. He could keep everyone’s attention on him all the time (the emergency broadcast system didn’t hurt). And once their attention was on him, he could delight them, enrage them, or at least keep them engaged. And he never stopped. Hugo Chavez was the marathon runner of dictators.

In 2012, while he was dying of cancer, Chavez gave “a state of the nation address lasting nine and a half hours. A record. No break, no pause.” Put a TV camera in front of him, and the man was a machine. If he had been an ordinary celebrity, he would be remembered as a legend. But he went too far. He became his TV show. He optimized national policy for ratings. The book goes into detail on one broadcast in particular, where he was filmed walking down Venezuela’s central square, talking to friends. He remarked on how the square needed more monuments to glorious heroes. But where could he put them? The camera shifted to a mall selling luxury goods. A lightbulb went on over the dictator’s head: they could expropriate the property of the rich capitalist elites who owned the mall, and build the monument there. Make it so! Had this been planned, or was it really a momentary whim? Nobody knew. Then he would move on to some other topic. An ordinary citizen would call in and describe a problem. Chavez would be outraged, and immediately declare a law which solved that problem in the most extreme possible way. Was this staged? Was it a law he had been considering anyway? Again, hard to tell. Sometimes everyone in government would ignore his decisions to see if he forgot about them. Sometimes he did. Other times he didn’t, and would demand they be implemented immediately. Nobody ever had a followup plan. They expropriated the mall, but Chavez’s train of thought had already moved on, and nobody had budgeted for the glorious monuments he had promised. The mall sat empty; it became a dilapidated eyesore. Laws declared on the spur of the moment to sound maximally sympathetic to one person’s specific problem do not, when combined into a legal system, form a great basis for governing a country. But Chavez TV was also a game show. The contestants were government ministers. The prize was not getting fired. Offenses included speaking out against Chavez:

…or taking any independent action:

…or, worst of all, not enjoying Chavez’s TV shows enough:

How did a once-great nation reach this point? I read Rory Carroll’s Comandante to find out. II. Venezuela was a typical Latin American country - Indians, conquistadors, strongmen - until the discovery of oil in the early 1900s. Foreign oil companies briefly resisted taxation. But over the 20th century the government gradually got them under control. In 1976, they finally nationalized the industry entirely under a government-run company, PDVSA. Venezuela is believed to have more oil - and more oil per person - than Saudi Arabia. In the 1970s, the Arab Oil Crisis pushed prices up and made Venezuela the richest country in Latin America. GDP per capita approached the level of Italy and Germany. Caracas became an international capital of business and culture.  But it was also one of the most unequal societies in the world. Oil money went mostly to the well-connected elites. These elites ran both major political parties, which agreed not to compete too hard against each other. Whoever was in power served elite interests and kept the masses placated with generous subsidies. When oil prices dropped in the 1980s, the subsidies dried up. In 1989, mounting anger exploded into a series of riots in Caracas; between 200 and 2000 people died. The government crushed the protests and managed to barely hang onto power. Enter Hugo Chavez. He was born in 1954, to a lower-middle-class family in an outlying province (later he would falsely claim to have risen from desperate poverty). Young Hugo loved baseball. His favorite player was his namesake, Isaias Chavez, who had risen from the Caracas suburbs to reach the US Major Leagues. When Isaias died tragically in a plane crash, 14 year old Hugo was heartbroken. “I even came up with a little prayer I recited every night, vowing to grow up to be like him.” When he came of age, he decided to join the army, on the grounds that the military academies had good baseball teams. But to everyone’s surprise including his own, he liked the army. No man can serve two masters, and for a few years, he struggled over which dream to pursue. But finally:

But Chavez stayed the same overly serious, overdramatic young person as always. And his hero-worshipping tendencies found a new target: Simon Bolivar, the Great Liberator, the man who had first won Latin America its freedom from Spain. Comandante seems confused exactly how Chavez ended up so left-wing. Bolivar-worship was par for the course, but most military recruits took it in a conservative direction. It can only say that Chavez met some left-wing activists, and visited Peru when it was making its own left turn. Still, it seems that pretty early, Chavez had come up with an unorthodox fusion of Bolivarism and communism, mixed with a sense of personal destiny. A diary entry from 1977, addressed to Bolivar, said:

And in 1982, when Chavez was 28, he led two friends to a holy shrine - a tree that Bolivar used to rest under - and:

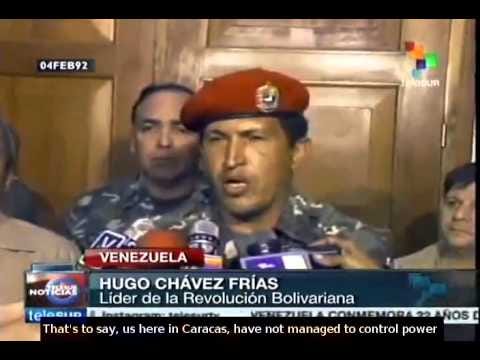

By the 1990s, Chavez - by all accounts personable and charismatic - had risen through the ranks and made friends with other leading officers. In 1992, when the government that had crushed the recent riots seemed poised to get away with it, Chavez organized a coup (rumor was army leadership was aware, expected him to fail, and let him do it because for complicated reasons it would help them score political points). The coup failed. Chavez surrendered. But the countercoup forces made a fatal mistake. They put Chavez on TV to tell his remaining forces to stand down. He did. But while on TV, he was unrepentant and charismatic and gave a fiery speech. This put him in position to try the Hitler Slingshot Manuever: fail at a coup, get pardoned, and leverage your post-coup fame to seek legitimate election.  Chavez’s pardon came two years later, at the hands of politician Rafael Caldera - who may have been in on the coup all along. Four years afterwards, he won a fair presidential election and took power. III. This is the point where I’m supposed to explain how Chavez went from democratically-elected president to dictator. It’s tough, because it’s debatable how much of a dictator he was. He continued to hold mostly fair elections throughout his reign. His party even lost some of them! He certainly didn’t murder his enemies as consistently as Putin. He wasn’t even consistent about locking them up. Carroll describes one enemy, a judge who sometimes ruled against him. Chavez jailed her, but forgot (?) to take away her cell phone. She kept posting anti-Chavez tirades from her jail cell, Chavez kept posting bombastic responses, but the thought that she was in jail and he could rough her up or at least steal her phone never really got through to him. Part of Chavez’s appeal was that he was more of a clown than a chessmaster, and this percolated through to his dictatorial style. Instead of firing squads at midnight, Chavez was authoritarian in the way that American conservatives claim that wokeness is “creeping authoritarianism”. He and his network of allies controlled the media, the institutions, and all the good jobs. If you flattered him, the media would say nice things about you, you would get preferential treatment when interfacing with institutions, and could count on a well-paying sinecure at some government department or nationalized company. If you questioned his rule, you would find that every news story about you was negative, and you were locked out of any job besides janitor or taxi driver. For example: in 2003, the economy sputtered, and opponents sensed weakness. They organized a campaign to recall Chavez. Venezuelan law requires a certain percent of the population sign a recall petition. The opponents got it: three million signatories. Chavez survived the recall and hung on to power. And:

I like this passage. It tells us many things:

But as much as we complain about this kind of thing in the West, Venezuela has it worse. Partly this is because of how centralized and official it is under one guy. But mostly it’s because Venezuela doesn’t have much private sector or civil society. Remember, think of it as Saudi Arabia with better weather. The (government-owned) oil company is the ultimate source of all wealth. That was true even before Chavez. Chavez then expropriated most private industries, and mismanaged the rest into bankruptcy. But he compensated for this with his own set of oil-subsidized institutions and outright oil subsidies. As always, you get rich (or middle class) by standing in front of the giant geyser of oil money. And Chavez got to control who did that. IV. But fine. Let’s set the word “dictator” aside, and try to get back to the story of how he went from weak democratically-elected president to the sort of guy who could get all his opponents blacklisted and destroy all private industry. Hugo Chavez took office in 1999. At first, he wasn’t much of a strongman:

But Chavez was biding his time. In mid-1999, he called for a Constituent Assembly to rewrite the Constitution. Chavez's supporters won 52% of the votes for assembly members, but because Chavez got to set the vote -> seating rules, they got 95% of the seats. The Assembly voted itself the right to remove "corrupt" government officials, which turned out to mean judges opposed to Chavez. It increased presidential power, lengthened presidential terms, made various appointed positions open to election, and eliminated the upper house of the formerly bicameral legislature (it also passed a laundry list of left-wing policy reforms, like giving indigenous peoples guaranteed seats in Congress). His next target was PDVSA, the oil company. In all the previous decades of corruption, the elites had been smart enough not to injure the golden goose. The oil company was an island of relative competence, run by technocrats, oligarchs, and economists. They fancied themselves above the civilian government, and although they would graciously share revenue with the state, they weren’t going to play by its rules. Chavez played a cat-and-mouse game, trying to use his limited presidential powers to frustrate and humiliate them as much as possible. Finally, he tried a frontal assault:

The oil executives and their oligarch supporters called a general strike. Millions of Chavez opponents took to the streets. They were supposed to march to the oil company headquarters, but “spontaneously” shifted course to the presidential palace. Somehow - it was unclear exactly how - there was violence and some of them were massacred. This made the rest even angrier, and they rushed towards the palace to find and depose the President. Chavez fled. Pro- and anti-government forces agreed on a truce where Chavez would go into exile in Cuba, and business leader Pedro Carmona would become acting president. But Carmona quickly alienated everyone, including the military (who had been thinking this was a military coup and they were in control). Chavez’s supporters organized a counterdemonstration and removed Carmona with military backing, and Chavez came right back, triumphantly. Only a few people were charged. There wasn’t much retaliation. Everything was right back to before.  The strike-turning-into-a-coup having failed, the opposition tried an actual strike. For six weeks, companies aligned with the oil leadership - nearly all of them - stopped all production. There were massive shortages. Chavez, always focusing on what was most photogenic, sent in the army to restart production. The bizarre climax of this period was in a soda factory. The cameras rolling, a general burst into the factory, grabbed its hidden stockpile, and started gorging on soda in front of the cameras. Reporters peppered him with questions: isn’t this a threat to private property? Can targeted seizures really make up for a general stoppage of all production? In response to each question, the general let out a giant burp. For some reason this won the heart of the Venezuelan people - “he’s just like us!”.

With public opinion on his side, Chavez fired most of the workers at the oil company. This destroyed its institutional knowledge and competence. But there was an old Venezuelan joke: “The second most profitable business in the world, after a well-run oil company, is a badly-run oil company.” So the economy only sort of collapsed. This was when his opponents called the three-million-name referendum to recall him. Chavez had two secret weapons. First, he now controlled all the oil money. Second, he had a good friend in Fidel Castro of Cuba. The two men shared a passion for socialism. And Cuba’s socialist project was well underway and had lots of doctors and social workers. Using his oil money, Chavez paid for his Cuban allies to send in some of Venezuela’s first universally-available social services, including “twenty thousand Cuban doctors, nurses, and other specialists . . . teachers followed to teach the illiterate to read and write . . . credits and training were offered to small agricultural and industrial cooperatives . . . on it went: soup kitchens, subsidized food shops, land titles, flights to Cuba for eye surgery. By the time the referendum was held in August 2004, Chavez’s ratings had recovered, and he won in a landslide.” From here on, things were comparatively smooth sailing. Partly this was because the opposition had been discredited. Partly it was because Chavez had replaced the independent economy and civil society with oil subsidies and Cuban services loyal to him personally. And partly it was because the US invaded Iraq and drove up the price of oil, and suddenly Venezuela had even more infinite money than the near-infinite amount of money it had before. The amount of money oil consumers were throwing at Venezuela made it almost impossible for a shrewd president who had put himself in position to direct oil revenues to lose. And Chavez (mostly) didn’t lose. In 2006, he declined to renew the broadcast license for Venezuela’s main independent TV station. In 2007, he called a constitutional referendum to abolish term limits. This time he lost - the book says this was because Chavez had limited control over local government officials who would usually help get out the vote, and the referendum didn’t interest them. Two years later, he tried again, this time abolishing term limits for himself and local officials, and won 54-46. He banned foreign funding for NGOs, accusing them of being tools of American capitalism. Problems started creeping in around 2008. The global financial crisis didn’t just hit Venezuela directly. It also lowered the price of oil. It became apparent that Chavez had been hollowing out the sort of rule of law it took for the economy to function, and plastering over the cracks with infinite oil money. As the oil money became a mere torrent rather than a giant flood, some of the cracks started to re-open. Carroll discusses the situation in Ciudad Guayana, Venezuela’s “industrial heartland”. During the late 20th century, the Venezuelan elites had invested in it as the harbinger of a new self-sufficient Venezuela full of high-tech factories and good manufacturing jobs. At first, it seemed to be working. As part of his popular policies, Chavez had subsidized cheap electricity, until Venezuela’s citizens were “per capita the continent’s biggest energy guzzlers”. In 2010, drought struck Venezuela’s hydroelectric dams, which produced the majority of the country’s power, making such consumption unsustainable. Instead of withdrawing the subsidies, Chavez chose to knife industry. He shut down most of Ciudad Guayana’s factories, some of them so suddenly that “entire plants were ruined”.

The good news was that “the firm had not fired a single worker” - Chavez just added all of them to the oil subsidy payroll!  This seemed typical of Venezuelan companies’ experience:

And:

And:

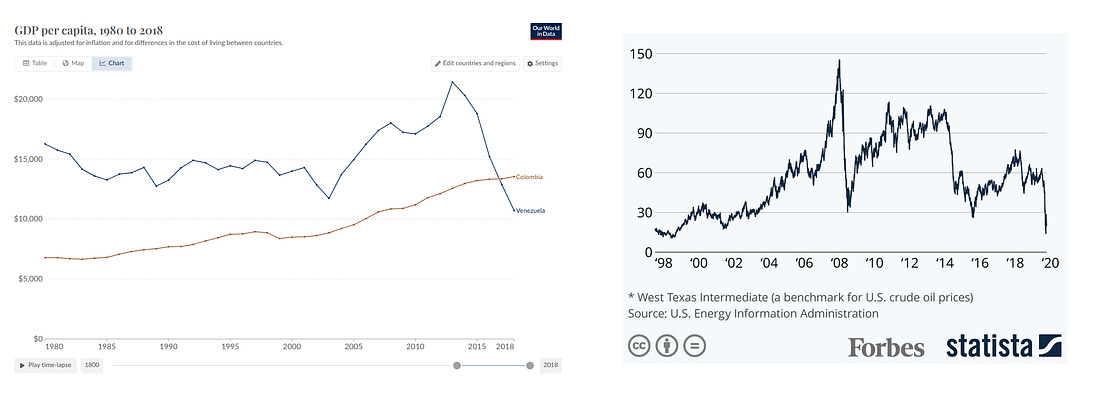

Left: GDP per capita of Venezuela (blue) vs. neighbor Colombia (red). Right: price per barrel of crude oil. When crude starts going up, so does Venezuela's GDP. But when it starts going down, Venezuela's economy is revealed to be so hollowed out that GDP crashes even lower than it was before at the same oil price. Chavez was spared the worst of it. He died of cancer in 2013, when crude oil prices were still high enough to disguise some of the damage he did to Venezuela. In 2015, prices crashed, and it became obvious that without his system of subsidies, the economy had completely ceased to function. V. So in a few short paragraphs, what went wrong? There’s a known flaw in democracy. Candidates can temporarily increase their popularity by doing things which are popular even though they’re bad ideas. Guarantee low prices by jailing any merchant who charges above a certain amount. Confiscate land and business from out-of-touch rich people. Declare generous gasoline subsidies for all, payment to be handled later. Do these enough, and the country collapses. In sufficiently intense electoral competition, why doesn’t everyone do these all the time? Partly you hope for an educated electorate that doesn’t fall for them. Partly you hope that the country has enough non-elected elites that they can stop this kind of thing. And partly you hope that the consequences of such mismanagement accrues quickly enough to hurt the candidates and parties who propose it. But Chavez was psychologically addicted to maximizing his own immediate popularity any given moment. He was able to use the rhetoric of communism to steamroll over the educated elites who tried to stop him. And he had enough oil money to defy gravity for a very long time, burying the feedback signals that would otherwise have told him to slow down. So, the usual question: could it happen here? Here are three answers: 1) America is no stranger to politicians wooing the electorate with bad economic policy. The most obvious case is Trump’s tariffs, but it’s silly to pick on something so out-of-the-ordinary when this is such a standard part of the game. Look at the American regulatory state, and lots of it is ruinous ideas that probably sounded good to people who didn’t understand economics. Take a random Chavez proposal, call it “the Green New Deal”, and publish an editorial saying it will “make the one percent pay”, and half the US electorate will start protesting for it immediately.  So a more focused question would be: what are the factors causing it to happen here at some slow rate but no faster? And should we be concerned that those factors will disappear, leading to a Chavez-like collapse? I don’t have a great answer here. My best guess would be that we don’t have Venezuelan levels of oil wealth, politicians understand that voters will punish them if they destroy the economy, and so they try to avoid doing that. Chavez got saved a couple of times by sudden oil windfalls and the Cubans; without them, he wouldn’t have made it. I suppose that’s true here too. 2) Chavez used the usual dictatorial tools that we’re well-protected against. In particular, he benefitted from a constitutional assembly; he was able to plan it so that a 52% showing by his party led to control of 95% of the seats, essentially letting him rewrite the constitution and gain unlimited power. Most western countries have better constitutional amendment processes than this, so we’re probably safe. The Chavistas also benefitted from being able to refuse to renew opponents’ broadcasting licenses; I don’t know what our broadcasting license policy is here, but I never hear about this being an issue so I’m guessing we’re probably safe. And the continued independence of Facebook and (especially) Twitter means broadcast TV doesn’t have the same monopoly on information here that it probably did in Venezuela. I think we’re safe here too. 3) Chavez reminded me more of Trump than any of the other dictators I’ve profiled. This surprised me, because the other dictators were “right wing populists”, a designation people often apply to Trump, and Chavez was a left-wing revolutionary. Still, something about him feels deeply familiar. Chavez was, first and foremost, a great entertainer. He kept people watching by being funny, unpredictable, and - by the standards of a usually dignified political system - hilariously offensive. Partly this was because it was politically advantageous for him to have everyone talking about him. But partly he was an obligate narcissist and couldn’t have stopped it if he tried. He had zero loyalty, ran through ministers quickly, and ended up with a cabinet of mediocrities whose only virtue was complete willingness to flatter him and do whatever he said. He took great photo ops but was too distracted to ever really follow through on his grand plans. He was vicious in insulting his opponents, but too distracted to ever really neuter them entirely. So Chavez feels like what happens if you get a left-wing Trump who’s a little more competent and then benefits from enough of an oil windfall that nobody can get rid of him. It’s not pretty. Carroll ends his book at Chavez’s death. He paints a picture of a system centered entirely around one man, his frenetic work schedule, and his cult of personality. Nicolas Maduro appears only as the flatterer-in-chief, a former bus driver with no personality of his own. Given Chavez’s inability to ever really get rid of his opponents, and his tendency to pick mediocrities who can’t govern on their own, I find it surprising that Maduro has lasted this long, staying in power despite the collapse of the petrostate and Venezuela feeling the full brunt of its bad decisions. This book gives no explanation for why that would happen. A very quick look at Wikipedia suggests Maduro simply used Chavez’s popularity among the military and police sectors to launch a more traditional dictatorship and suspend all elections. Probably there’s something to be learned here about the thin and porous border between illiberal democracy and true dictatorship, but I would want to know more about Maduro and recent history before making any strong claims. For whatever reason, I find Chavez scarier than most of the other dictators I’ve been reading about. The others seem like aberrations of democracy. Chavez seems like its monstrous perfection, a reminder that in the absence of virtue, what appeals to the people can be the opposite of what’s good for the state. If there’s good news, it’s that his rule was always rather weak, only propped up by the unusual circumstances of Venezuela’s particular resource curse, and required a switch to full dictatorship after one generation.

You're currently a free subscriber to Astral Codex Ten. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Older messages

Mantic Monday 10/30/23

Tuesday, October 31, 2023

Manifest || Manifold.Love || Eyeless in Gaza

Open Thread 300

Monday, October 30, 2023

...

My Left Kidney

Friday, October 27, 2023

...

Open Thread 299

Monday, October 23, 2023

...

Open Thread 298

Thursday, October 19, 2023

...

You Might Also Like

Veterans Administration therapists forced to provide mental health counseling in open cubicles

Monday, March 10, 2025

As part of the Trump administration's frenzied push to end remote work arrangements for federal government workers, the Veterans Administration (VA) is forcing therapists to provide mental health

Armed Man Shot Near White House, Russian Spy Ring, and Jet Lightning

Monday, March 10, 2025

Secret Service agents shot and wounded an “armed man” a block from the White House shortly after midnight Sunday while President Trump was away for the weekend. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Numlock News: March 10, 2025 • Crater, Mickey 17, Hurricane

Monday, March 10, 2025

By Walt Hickey ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Open Thread 372

Monday, March 10, 2025

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

☕ Spending spree

Monday, March 10, 2025

European markets are outpacing the US... March 10, 2025 View Online | Sign Up | Shop Morning Brew Presented By Tubi Good morning, and Happy Mario Day (MAR10). Traditional celebrations include: reckless

Surprise! People don't want AI deciding who gets a kidney transplant and who dies or endures years of misery [Mon Mar 10 2025]

Monday, March 10, 2025

Hi The Register Subscriber | Log in The Register Daily Headlines 10 March 2025 AI Surprise! People don't want AI deciding who gets a kidney transplant and who dies or endures years of misery

How to Keep Providing Gender-Affirming Care Despite Anti-Trans Attacks

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Using lessons learned defending abortion, some providers are digging in to serve their trans patients despite legal attacks. Most Read Columbia Bent Over Backward to Appease Right-Wing, Pro-Israel

Guest Newsletter: Five Books

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Five Books features in-depth author interviews recommending five books on a theme Guest Newsletter: Five Books By Sylvia Bishop • 9 Mar 2025 View in browser View in browser Five Books features in-depth

GeekWire's Most-Read Stories of the Week

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Catch up on the top tech stories from this past week. Here are the headlines that people have been reading on GeekWire. ADVERTISEMENT GeekWire SPONSOR MESSAGE: Revisit defining moments, explore new

10 Things That Delighted Us Last Week: From Seafoam-Green Tights to June Squibb’s Laundry Basket

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Plus: Half off CosRx's Snail Mucin Essence (today only!) The Strategist Logo Every product is independently selected by editors. If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an