👋 Hey, I’m Lenny and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career.

P.S. Don’t miss Lennybot—my AI chatbot that’s trained on every newsletter post and podcast interview. It’s very good.

Q: When do companies typically hire their first product manager?

I reached out to 30 companies to find this out, and here you go:

Takeaways:

Everyone hires a product manager eventually.

The typical company waited two to three years to hire their first product manager. They typically had 10 to 15 engineers and 15 to 25 total employees. But the ranges are wide, so don’t use this as a hard-and-fast rule.

Surprisingly, more than half of companies hired their first PM before finding product-market fit, which is counter to the advice you hear. Particularly in B2B.

No founder told me they regretted bringing on a PM, but some companies, including Notion, shared that they regretted waiting so long. Though others, like Stripe, were happy they wanted so long.

Most first PMs were previously individual-contributor product managers, or senior PMs. Very few were previously former directors, VPs, or heads of product. Surprisingly, almost a fourth were engineers.

Interestingly, many companies with a strong product founder hired a PM very early. Coda and Snyk (who both had PM founders) hired their PM essentially as their first employee, and Slack (with Stewart Butterfield) just over a year in.

In terms of timing, there’s no one way to do it. Companies that hired a PM early did great (e.g. Snyk, Ramp, Slack), and companies that waited a long time (e.g. Stripe, Figma, Notion) did great.

Companies that waited a long time to hire their PM had different reasons to wait:

Notion spent much of that time (about three years) looking for product-market fit.

Stripe was building an engineering-oriented product and hired top-tier product-minded engineers, so they didn’t have a strong need for PMs.

Snap hired designers who took on the PM duties, which, from what I hear, ended up being fairly chaotic. They eventually hired a PM to lead their initial monetization efforts.

Companies that hired a PM early, like Ramp and Snyk, did so because they didn’t have the skills or time to do the product job well, and they knew their product would make or break the business. More on this below.

No matter how long you wait, whether you have a PM or not, someone will be doing the PM duties.

If you’re looking to push out your first PM hire, the questions you need to ask yourself are:

Do you want to be doing this work?

Are you good at it?

What are you not spending time on that you could be, if you had a PM?

Generally, the sequence is: a founder takes on the PM duties, they then divide up the duties among the early engineers and designers, and then eventually they bring on a full-time product manager.

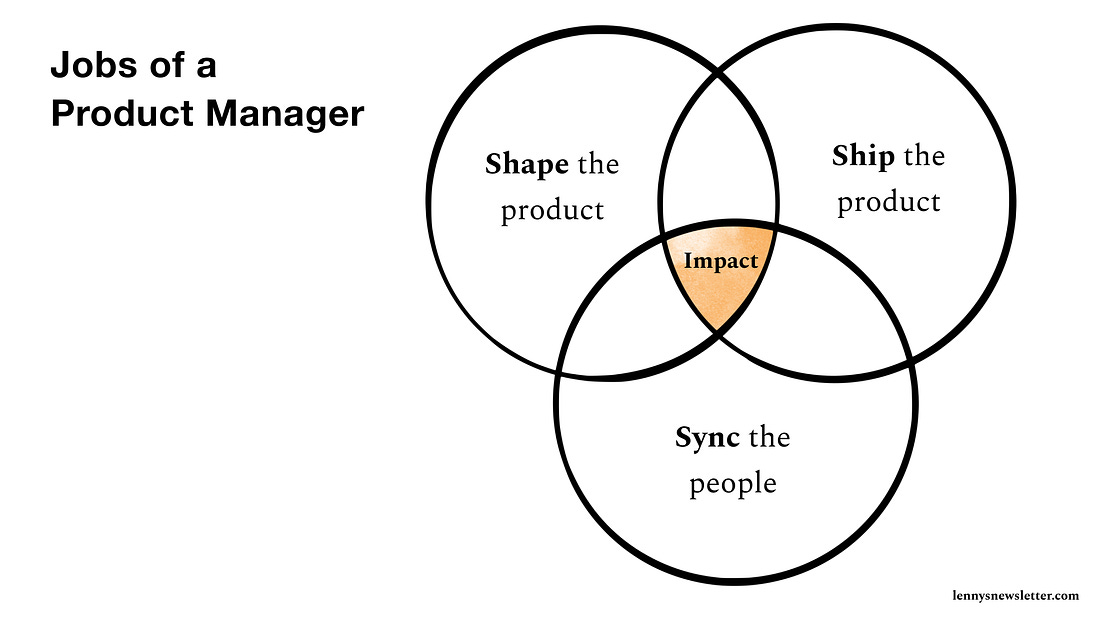

Here’s a simple way to think about the jobs of a product manager:

Shape the product: Harness insights from customers, stakeholders, and data to prioritize and build a product that will have optimal impact on the business.

Ship the product: Ship high-quality product on time and free of surprises.

Synchronize the people: Align all stakeholders around one vision, strategy, goal, roadmap, and timeline to avoid wasted time and effort.

Here’s a bunch of advice I collected from founders and early PMs on hiring your first PM:

From Geoff Charles, first PM at Ramp:

“A PM’s greatest value is bringing order. As the single point of contact for the team, they hold context and disseminate to the right folks, keep teams focused on building and shipping, and can make decisions quickly.”

From Ben Porterfield, co-founder of Looker:

“My co-founder and I were acting largely as PMs up until we hired Josh [Siegel]. But we were drowning in prospect calls and our own responsibilities. Bringing in a PM allowed us some breathing room. More importantly, it let us organize feedback from customers and prospects, generate higher-quality sales/marketing materials, and improve internal communication with various teams (e.g. feedback to engineering, roadmap plans for CS/sales/marketing, etc.).”

“What my PM role allowed was for our founders to have the bandwidth to do bigger conceptual thinking, since I’d taken over the product and project management of Zimride. Within a few months after I started, the founders hatched a plan for an entirely new business based on short-distance ridesharing, while I kept the Zimride product humming, allowing for experimentation. That experiment became Lyft.”

—Evan Goldin, first PM at Lyft

From Sarah Tavel, first PM at Pinterest:

“You as the founders know what needs to be built, but you need hands to execute. In the beginning, it’s about getting leverage, and to get leverage, you need someone you trust.

It doesn’t need to be a senior person who is figuring out what to build, but it does need to be someone who really understands your product and can effectively channel you, communicate well, and know what decisions/details to surface.”

From Badrul Farooqi, first PM at Figma:

“Initially the main benefit was more diligent support on execution and not letting small (but important) things fall through the cracks. Better weekly rhythm for the team, better triaging of all incoming issues, identifying harder product decisions quickly. Less focus initially on vision, big roadmap exercises, exec presentations, etc. Basically, things are working pretty well and we need smaller and consistent improvements to keep it that way.”

From Calvin French-Owen, co-founder of Segment:

“For us, Alex [Millet] took on trying to harness the thorniest part of our business. We were getting dozens of tickets per day, from customers who all wanted our hundreds of integrations to behave slightly differently. He took on the prioritization work around which customers to listen to, how to sequence work-in-progress, and some sort of sense of taste for how to solve it.”

“I’ve seen too many founders make the mistake of bringing in a ‘product person’ to fix the fact that they don’t have PMF and figure out the product strategy almost from scratch. Bring in a PM when you’re confident about the direction you’re heading. It’s the founders’ jobs to set the strategic direction of the company.

Adding our first PM brought critical additional bandwidth that unlocked engineers to focus on writing software. Additionally, having more product talent onboard enabled us to bring in the voice of the customer to the room and connect the dots between support, sales, and engineering.”

—Tomer London, co-founder and CPO of Gusto

From Calvin French-Owen, co-founder of Segment:

“The founders should be okay handing off product decisions. The biggest problem I see is when founders don’t really want to cede control. This works best when the founders are still on the hook for approval and high-level decision-making but can delegate some of the lower-level decisions.”

From Kenneth Berger, the first PM at Slack:

“Ask yourself if you’re ready to trust someone else with your beloved product. Many founders desperately want help but also aren’t willing to trust an outsider. To set them up for success, choose to trust them and give them plenty of feedback to build alignment over time.

Often founders are operating from a ‘trust is earned’ mental model, so by default they don’t trust their employees and expect them to earn that respect over time. But those employees are operating at a distinct disadvantage. Especially when they get started, they won’t have anywhere near the level of commitment and experience of a founder. Both employee and founder are set up to fail under this model. Churn and frustration is the result; this is why you see so many startup execs exit after a year or less.

The alternative to ‘trust is earned’ (low trust) is ‘trust is given’ (high trust). In this model, you choose to trust your employee on principle. Once you believe they’re trustworthy, any gaps tend to look less like unsolvable character flaws and more like opportunities for coaching/feedback. This model is more about the founder trusting themselves. Trusting themselves to source the right people, to interview them effectively, to coach them to high performance, and to promote them or let them go depending on the fit. Trusting themselves to deal with the discomfort of delegating out product decisions, versus blaming the employee and putting that burden on them.

In a high-trust environment, it’s easy to repair mistakes and build increasing independence over time. In a low-trust environment, mistakes feel like threats to safety, and thus employees tend to get fired to help the founder feel safe. Mistakes are inevitable in any role, but especially in a high-profile, critical role like head of product or first PM—so it’s best to plan for those mistakes and have a plan to coach through them.”

Including Notion, Looker, Figma, Robinhood, Segment, Amplitude, and Linear:

“Our first PM actually joined as a growth PM, and I found that to be a good role to start the product org. If you’re a product founder, finding a good core PM as your first PM is very hard, whereas growth PM can actually be very complementary to the founder’s core product skill set.”

—Akshay Kothari, co-founder of Notion

“We transitioned an internal analyst (effectively a software engineer, already working with customers on building their LookML models for a while) about 1.5 years into building the company. His name was Josh Siegel, and he was really smart and really focused on the product. He used to deliver long emails after prospect meetings about all the things the prospect needed to be successful. He also was clearly already capable of translating the requests from what they said they wanted to what the product should actually deliver—not an easy task. He became our first PM, which continued at that time to report up through engineering. The following two PMs were also internal transfers—we wanted people who deeply understood our product and our customers.”

—Ben Porterfield, co-founder of Looker

“Robinhood’s first PM was an iOS engineer originally, and then in 2016 (three years in) we decided it was time to add a PM to the mix. He had great product sense, knew the front end and API, and had been through several product cycles.”

—Jaren Glover, early engineer at Robinhood

“I didn’t start with a PM title. The formal titles came later at Figma, once the company needed more discrete roles and seniority throughout the company.”

—Badrul Farooqi, first PM at Figma

“We had nobody with the title ‘PM’ until something like 30 to 40 people. We were 10 to 12 engineers; it was mostly the founders acting as PMs and then individual engineers and designers at the company designing features for the first two years. Alex Millet was probably the person who was closest to a pure PM, originally hired in September 2014 as a sort of forward-deployed engineer who then started prioritizing integration fixes and working with customers sometime in late 2014.

We sort of realized all at once that we could benefit from having PMs (around mid-2015?). Instead of hiring externally, we hired internally and formed a product team with Alex, Kevin Niparko, and Chris Sperandio.”

—Calvin French-Owen, co-founder of Segment

“We got really lucky with Justin [Bauer], who started out as director of product, turned into our CPO, and ran the function for eight years. He proactively had heard about the product and sought us out to join the team. It probably would have taken a lot longer if he hadn’t done that, as hiring good PMs is hard!”

—Spenser Skates, founder and CEO of Amplitude

“We didn’t outright seek to hire a PM or head of product. Nan [Yu] actually started as a contractor to help us lay out the foundation and roadmap for Linear Insights, our analytics product. We didn’t internally have strong knowledge on analytics, and he was the perfect person to help the team; he had been an engineering leader and more recently led product for Mode Analytics. Working together on the project, it became clear he would be a fit for us and could lead more complex product features as we founders started to lack time to focus on them. Contract-to-hire was also the perfect way for us to experience a new type of skill set on the team in a less risky way, even though it was not the original intention.”

—Jori Lallo, co-founder of Linear

“Hiring a great PM can be tricky because the interview process only tells you so much, but one way to make sure they’re a good fit is to hire a PM that you’re confident brings an IC superpower to the table (design/UX, for example) or is otherwise very technical or a subject-matter expert in your field (for Ramp, fintech). Make sure cross-functional stakeholders have a say in PM hiring, as PM–technical lead–design lead chemistry is super-important.”

—Karim Atiyeh, co-founder and CTO of Ramp

“In my own experience, the best PMs fall in love with the problem and the space. PMs in particular benefit from a passion for the customer in a way that other roles don’t require. The engineers and designers have to trust the PM, and that is hard to do if the PM isn’t a font of customer/ecosystem knowledge.”

—Calvin French-Owen, co-founder of Segment

“Looking back, I’d say choosing someone like Josh [Siegel], who had good product intuition, and ensuring that there’s clarity around how bringing in the PM changes things or doesn’t (how is roadmap now decided, where are co-founders’ responsibilities and PM responsibilities shared and where are they delineated, etc.).”

—Ben Porterfield, co-founder of Looker

“Engineers in smaller companies are understandably nervous about adding a PM, so have the first PM identify and lead quick, easy wins to prove their value immediately. Do this even before setting up a longer-term product roadmap. The product VP (Awaneesh Verma) and I came from much larger companies (Google and Microsoft). We had to switch to a scrappy mindset right away. The low-cost, high-impact experiments we prioritized in our first months showed the company how we could help them unlock the next stage of growth.”

—Kai Loh, first PM at Duolingo

Stories from Coda, Snyk, and Persona:

“It all depends on the type of startup. Some startups are all technical insight/risk, and you want to get those core engineers in place right away. If, for example, you have a startup that is mostly regulatory risk, you would want to get someone familiar with that set of regulators early.

For Coda, most of our insight (and risk) was in the product (is it actually possible to build a new all-in-one blinking cursor? And what are the key choices that enable ‘docs as powerful as apps’). So we asked Matt Hudson (@buddy) to join in very early. He’s a supremely talented product thinker and also has really deep passion and instincts for our space.”

—Shishir Mehrotra, co-founder and CEO of Coda

“I believed the fact that security products weren’t fit for developers was a product problem, not a tech problem, needing breakthroughs more in the UX world than tech algorithms. Furthermore, I had two technical co-founders that I knew would lead the security and tech aspects well, so felt I’m well-covered there.

I could have done the product work myself (and in practice, I did a portion of it), but I wanted to free myself up to build the company as a whole, and not be too focused on one aspect of it. I did hire someone with deep UX skills, better than mine, who complemented me, not just offloaded work.

In general, I intentionally took the path of building a strong leadership team early on. It was always a very hands-on leadership team, who initially spent most of their time as ICs but were also building teams and practices. This is a personal choice, and many founders prefer to directly manage most of the team until it grows. For me, however, I perceive myself as a better leader and innovator than I am a manager, and I wanted to focus my attention there.”

—Guy Podjarny, founder and CEO of Snyk

“We hired Vincent [Tsao] because Charles [Yeh] and I believed his professional experience and willingness to give it his all were a perfect fit. We would’ve wanted to work with him whether at Persona or elsewhere, and that speaks highly of our rapport. He had experience from a previous startup and understood the fluid nature of a company’s early stages—he wasn’t tied to a specific role, title, or set of responsibilities and understood that we were all going to do whatever it took to succeed. In fact, his very first project had nothing to do with product—he spent the first evening setting up payroll!

We also believe that many founders, in their eagerness to launch and iterate, often swing too far on the pendulum of no documentation or process. While Charles and I were confident in our product and market insights, as well as our ability as engineers to create a minimum viable product (MVP), we were also self-aware about our shortcomings. We knew we needed someone with not only sharp product intuition but also someone who could anchor our product operations and knowledge base, synthesizing insights from chaos and ultimately helping us move faster. Vincent was invaluable in building the foundation that enabled us to smoothly go from MVP to product-market fit and, eventually, to scaling our team.”

—Rick Song, founder and CEO of Persona

“If the relationship between the product and the customer is complex and involves different stakeholders (like B2B software), then hiring a PM sooner can be helpful.

If it’s more straightforward, like most consumer experiences, hiring a PM will almost certainly disempower engineering leaders and design, so you have to be very careful and clearly think about why you need someone between leadership and those who are actually building.” —Anonymous

As you look back at the chart above, I’m curious if you see any other takeaways or surprises. Any other lessons, insights, or data points? Leave a comment! I’d love to hear from you.

Leave a comment

When to hire your first product manager (my first attempt at this question)

Advice for joining as the first product manager

Hiring your early team in B2B

Have a fulfilling and productive week 🙏

I’m piloting a white-glove recruiting service for product roles, working with a few select companies at a time. If you’re hiring for senior product roles, apply below.

Apply to join

If you’re exploring new opportunities yourself, use the same button above to sign up. We’ll send over personalized opportunities from hand-selected companies if we think there’s a fit. Nobody gets your info until you allow them to, and you can leave anytime.

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already. There are group discounts, gift options, and referral bonuses available.

Sincerely,

Lenny