|

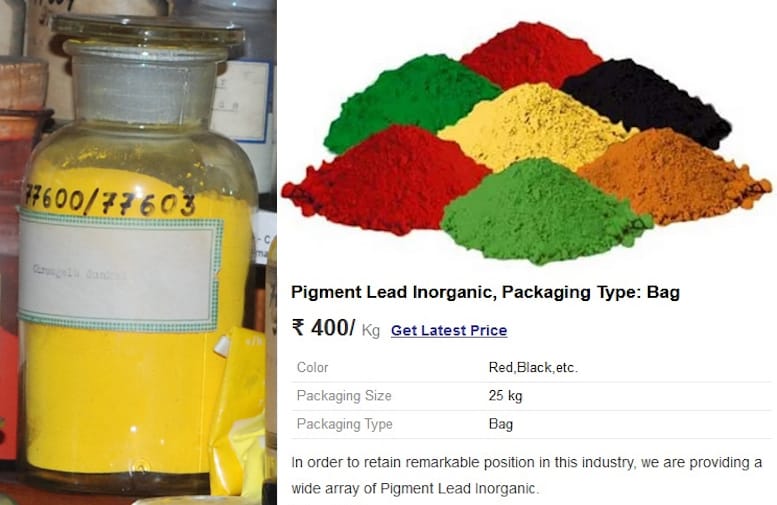

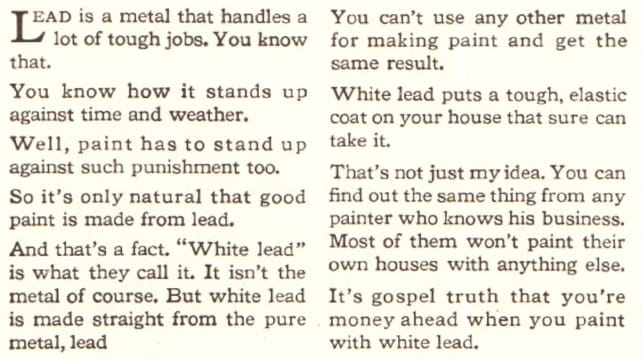

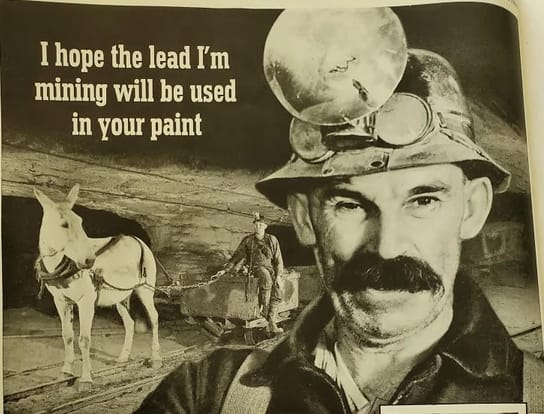

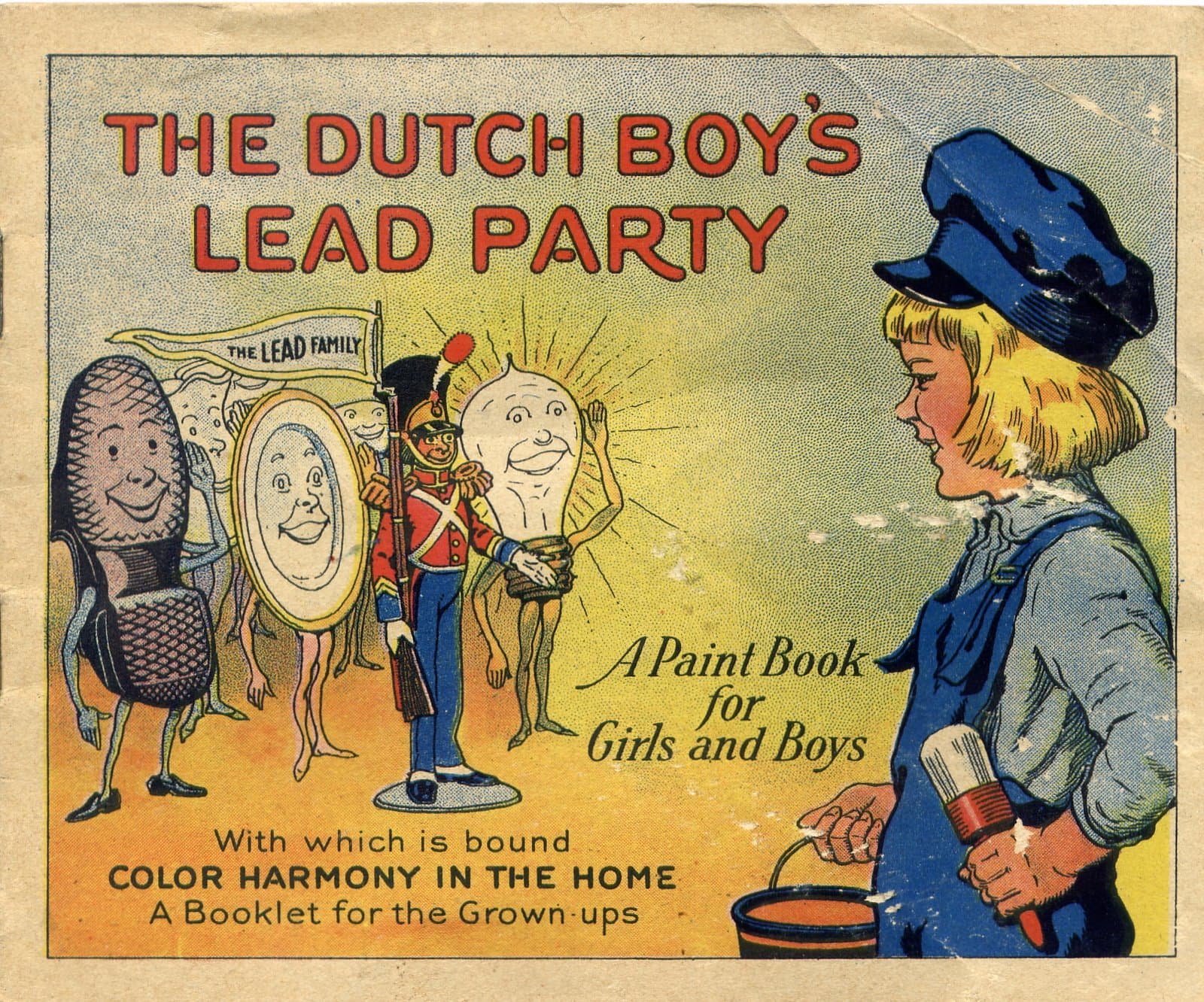

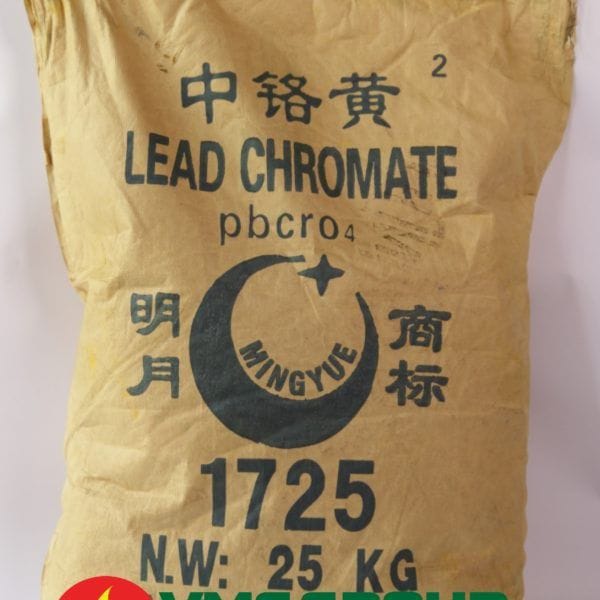

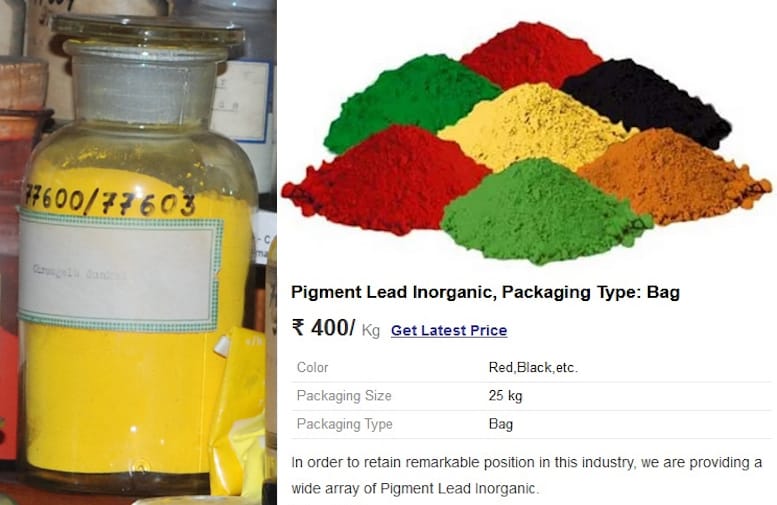

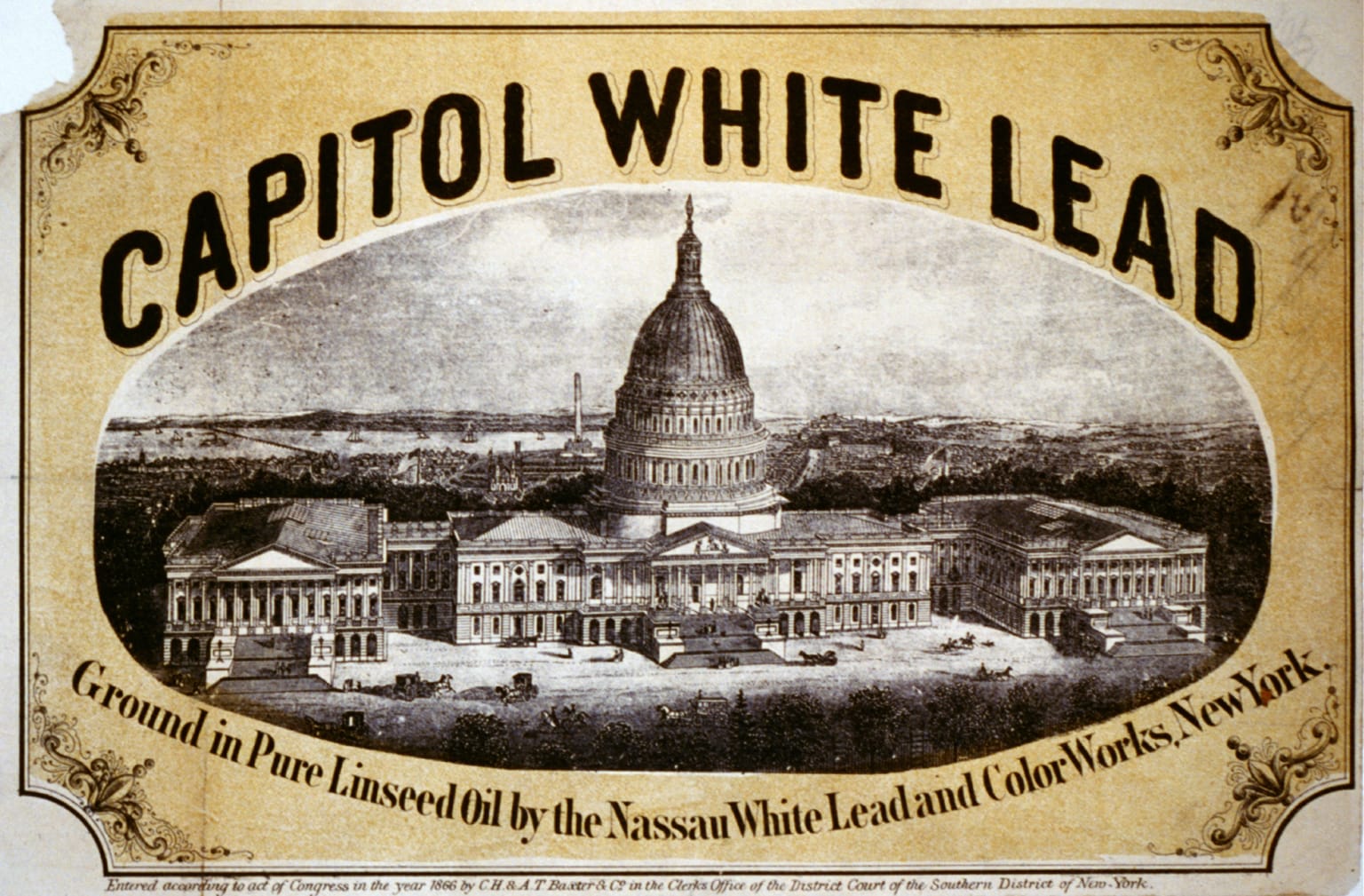

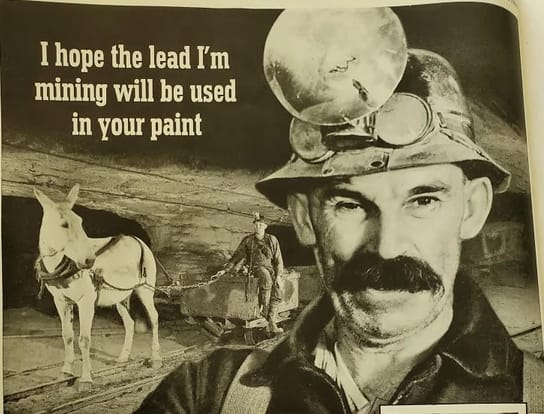

Since I first came to be interested in ghost signs, and their longevity, I've always heard the refrain that this was due to the lead in the paint. However, while not doubting the truth of the claim, I'd never received a satisfactory explanation for why that might be the case. Until now. In a casual conversation ahead of her BLAG Meet session, Jill Strong (@jill.strong.signs) let slip that she has a PhD in polymer photochemistry. I didn't hesitate to put the lead question directly to her, resulting in this in-depth exploration of the material, its properties and, of course, the major hazards associated with it. This is a lengthy article and most email systems won't display it in full. Sweet LeadBy Jill Strong  1-Shot Bulletin Colour (140-B, Light Green) with lead content warning on the label. “One coat covered like a dream, especially the yellows, oranges and reds.” — Liane Barker / @brushandpenstudio “It was wonderful paint! Dried very quickly, very hard, and was truly 'One-Shot' ... not the two-shot or even three-shot that we use now.” — Bob Dewhurst / @nevadahandpainted The enduring nostalgia of the older generation of sign painters for lead-based paints crops up time and again. But why—technically—did these toxic paints leave such a durable impression, not only as signs but on the people who used them? Were they really better than the paints we've got now and why? Lead Paint TypesFirstly, many people think that lead was a paint additive, in the same way tetra-ethyl lead was used as anti-knock petrol additive up until the 1970s. This is untrue. Lead compounds weren't just an additive; they were the paint itself. Here are three which were commonly used in paint manufacturing. White Lead White Lead is a mixture of lead (II) carbonate and lead (II) sulphate. It is a heavy white powder which accounts for most of the lead use in paint over the centuries. Along with red lead, it was one of the first synthetically produced pigments. Artistic literature, like Cennini's 15th century Il Libro dell Arte ('The Book of Art') recommended white lead as the best base for oil-based paints. It wasn't recommended for water-based paints or frescoes on account of the fact it had a tendency to blacken over time, but that didn't stop people using it. Because white lead has been used in fine art for centuries, it goes by many names, including: Lead White; Berlin White; London White; Cremnitz White; Flemmish White; Krems White; Dutch White Lead; Flake White; and Stack White. Some of these names refer to production methods, such as the DIY 'Dutch' or 'Stack' process. This involves leaving sheets of rolled lead stacked vertically in contact with vinegar fumes, traditionally activated by the warmth of heaps of rotting horse manure. When the temperature is right, lead carbonate and sulphate crystals grow on the metal surface like a thick, white mould. These eventually get too large, flake off, and collect at the bottom of the stack. This process allows a random variety of flake sizes to grow which oil painters deem to be very important and, for them, this process makes the very best white paint possible. Although these fine art oil paints aren't used for sign painting, I mention them because this obsession with the unique qualities of Stack White has led to a body of research that is helpful in answering our question. It's also important to note that besides being used as a white oil-based paint, white lead has a low tinting strength, and was the main ingredient for most other paints when mixed with pigments. Red LeadRed lead is a mixture of lead (II) and (IV) oxides, produced by roasting lead (II) oxide, which occurs naturally as an ore called litharge. It was known to the Romans as 'Minium' although this term can be confusing, as chemistry was in its infancy and other red pigments, including Cinnabar and Vermillion, went by the same name.  Lead samples for a sales representative of the Eagle-Pitcher Lead Co. from 1916. ‘Red' is also a slight misnomer here because it's actually more of a reddish orange. Oil-based red lead paints were, and still are, used as an anti-rust primer to protect all sorts of steel constructions, including bridges, train carriages and boats. Lead ChromateLead Chromate (PbCrO4) is not a paint base but a pigment which produces some intense oranges, yellows and greens. Lead chromate doesn't occur naturally; one production method involves treating litharge with chromic acid. Until the early 1970s, dark yellow lead chromate paint was used for American school buses. It was also used in the 1800s in Wisconsin to colour sweets, and turns up quite regularly as an illegal colour enhancer in ground turmeric in India and Pakistan.  Jar of 'Canary Yellow' lead chromate powder (Photo: Shisha-Tom), and an Indian website selling lead chromate pigments. Lead Paint PropertiesSo finely ground white or red lead powders mixed with linseed oil were the principal ingredients of lead-based paints. But these deceptively simple ingredients produced some unusual and impressive properties, namely texture, the siccative effect, durability, weight, photostability, and coverage. TextureOne of the first things the older generation of sign painters will mention is that lead-based paint had 'guts'—a good consistency. It was thick in the can and yet spread nicely when worked. Indeed, many photos of Stack white look remarkably like a hearty dollop of Cornish clotted cream. Most paints are thixotropic liquids, which means they're gel-like when left to sit, but once you dip a brush in, they spread like a liquid. This is due to weak bonds between molecules while the paint is undisturbed, which break as soon as any kind of movement is applied. (Ketchup and mayonnaise are also examples of thixotropic liquids, although lead based paints were much thicker.) Flake White is notorious amongst oil painters for being nearly impossible to squeeze out, and suppliers suggest 'gently massaging' the tube to liquefy the dense paint rather than resorting to more violent means. However, the liquid state wasn't to everyone's liking as Bob Dewhurst explains: “The new acrylic paints are certainly my choice on any kind of wall job. They're like jelly and you can just push 'em into the cracks, whereas the old 1-Shot was drooling all over the place.” Electron microscopy carried out by the fine art oil-painters shows white lead-based paint to have large, flat molecules which glide over each other, giving it this special consistency—imagine slippery micro-cornflakes all aligned in the same plane. When exposed to air, these molecules dry to form a strong, flexible coating with a relatively flat surface. This last point explains why lead-based paints had such a high gloss finish. Siccative EffectWhite lead powder added to any oil-based paint acts as a catalyst, helping it dry faster. In oil painting, this is called a 'siccative' effect. While this is beneficial to sign painters, it can also occur in the can, resulting in wastage and expense. Durability“When we see an old brick wall sign from a hundred years ago, we know that that's lead paint still holding up.” — Bob Dewhurst Lead carbonate/lead sulphate is highly photostable; it stays white even when subjected to intense solar radiation. Although linseed oil was the traditional binder for oil paints, over time it turns yellow as it oxidises. However, white lead seems to protect the linseed oil from oxidation, keeping it colourless. "You're money ahead when you paint with White Lead": 1939 advertising from the Lead Industries Association conveying the benefits of lead-based paints. Once dry, the paint is insoluble in water, which makes it resistant to rain. Additionally, the basic nature of the carbonate group also seems to offer some protection against the acids found in polluted air. Red lead-based primer is an incredibly tough paint too. For example, the lead chemically bonds to iron, creating a coating which resists even salt-water corrosion, making it ideal for coastal structures such as bridges and piers. WeightWith an atomic number of 82, lead is the heaviest, stable, naturally occurring atom. Heavier atoms do exist, but only fleetingly in laboratories or outer space. This density gave lead-based paints a superior weight for brush lettering. Sign painter Jack Halligan (@jack.halligan.792) says: “I recently lettered a truck with lead-free paint, but I was so unhappy with how it came out; my brushes weren't doing what I wanted them to. Also my script with Luco or French Master quills was quite sexy, but without the lead the quills were no longer suitable as the paint was like lettering with marshmallow fluff.” Jon Lloyd (@vintagesignpainterstl) agrees: “The old paint handled much better on the quill as the weight gave it a magnet-type effect on the surface, without the 'bounce' of modern paint.” This weight also had its drawbacks, especially for apprentices, as related by Mark Gill, fairground artist: “I remember Mr [Fred] Fowle telling me that in his early days at Lakins, he'd be sent down to the stores to get a 10 lb (4.5 kg) keg of white lead that they used as the base for mixing the colours. The paint shop was upstairs so he was half dead by the time he'd gone and got it.” Photostability“The biggest impact of the formula change was the shock that our usually reliable paints started to fade, especially reds, within a few years.” — Yvette Rutledge / @mysticbluesigns Photostability is related to durability, the difference being that one is the physical resistance of the coating to remain intact over time, while the other is its ability to resist changing colour. While working on a Victorian house, John Ton (@petalumasign) was given access to some of the original lead-based Morwear brand paint, noting that "the yellow still matched the weather-exposed walls!" The presence of the heavy metal in white lead-based paints also seems to preserve their pigments. In her paper on historical pigments, Alessia Coccato observes that "White lead somehow protects other pigments, even preventing 'ultramarine sickness'". This is when ultramarine oil paint loses its colour due to bacterial activity on the surface of the painting. However, this pigment protection doesn't last forever. The photo below shows a 50-year-old metal sign which is in my workshop for renovation. It was attached to the front of a guest house in the south of France and faced south-west—the most punishing here in terms of solar radiation.  While the black pigment is failing, the white-lead base remains. The original decoration consisted of one coat of red lead primer and one coat of lead white mixed with some yellow pigments to create a parchment colour. A sign painting enamel has been used for the black calligraphic lettering, and it's actually the black pigment in this enamel which has failed first. CoverageThe property of lead-based paints that most sign painters seem to miss most is its masking power. As Rob Weaver (@aknightofthebrush) puts it: “One coat always covered, no matter how much you thinned it.” X-ray crystallography confirms that lead carbonate forms a dense, highly cross-linked structure of flat molecules arranged in the same plane. This opacity effectively masks whatever happens to be underneath, and a small amount goes a long way. But health concerns were starting to surface.  1860s advertising for Capitol White Lead. Zinc oxide began to appear as a replacement for white lead in the late 1800s. Zinc is quite photostable, as long as the binder isn't linseed oil, which causes it to go yellow in sunlight. However, it lacks covering power, takes longer to dry, and becomes brittle much more quickly. Dr Marion Mecklenburg of the Smithsonian Institute suggests that zinc oxide can become brittle in as little as three years, even under museum conditions. The next contender to replace white lead was titanium dioxide, introduced in the 1920s. Optically more reflective (whiter) than white lead, and more opaque, oil painters shun it for being overpowering. It's hard to imagine a sign painter complaining about their lettering being too visible, but it does have other drawbacks—it is expensive and doesn't spread very well, having a naturally crumbly texture, requiring various additives to make it flow. Oil painter Marc Dalessio says: “For portraiture you absolutely have to use Lead White. Titanium white kills all the other colours, and lacks the beautiful transparency that almost mimics human flesh that lead has. Every great portrait [of a white person] was painted with lead." ✏️ Don't chew your pencil: Chemistry in the sixteenth century was sketchy to say the least. When a huge deposit of pure graphite was found in Cumbria in the north of England, it was mistaken for lead, being a dull, shiny grey deposit that looked like a metal and was soft enough to cut into fine canes. The name 'pencil lead' sticks to this day, but real lead has never been used in pencils, except perhaps to colour the outsides. Nearly everyone knows that lead is poisonous. It's been on the World Health Organisation's top-ten list of nasty chemicals to eradicate for as long as the list has existed. A number of recent medical studies also suggest that lead is actually more toxic than anyone previously suspected, and might even be responsible for one in ten deaths worldwide—that's more than HIV, malaria, suicide and car accidents combined. (I say 'nearly everyone knows' because a recent operation in Bangladesh to try and stop turmeric 'polishing' with lead chromate found some of the perpetrators didn't realise the powder was toxic and were feeding the contaminated spice to their own children!) If white and red lead were some of the first synthetic pigments, lead smelting was probably the first human-induced environmental hazard. In around 8000 BC in what is now Turkey, galena ore was heated to extract silver, and lead was a bi-product of this process. It seems likely that its weight and softness wouldn't have gone unnoticed.  This Lead Industries Association advertising from 1939 has sinister overtones in hindsight. Lead poisoning, also called Plumbism or Saturnism, was noted as early as 2000 BC; the Greek botanist Nicander described stomach cramps and paralysis in lead workers, while the Greek physician Dioscorides noted that it “makes the mind give way”. The problem is that, although lead is such a wonderful all-round ingredient for oil paints, it is absolutely useless for human health. It has no beneficial role in mammalian metabolism whatsoever, unlike some other metals such as zinc, copper and cobalt, which are essential micronutrients. But that hasn't stopped people ingesting it—sometimes even deliberately—for centuries. Lead Through the AgesThe Romans used lead in much the same way we use plastics; for everything they could. Produced by expendable slave populations, lead was cheap, malleable, durable, and revolutionary, because it could be rolled into tubes. They used this magical metal for water pipes, pots, pans, and tablewear, fashioned lead tablets to write on, minted coins, and lined coffins with it. Analysis of Mont Blanc ice cores suggests that Roman-era mining activities increased atmospheric lead concentrations in Europe by a factor of at least ten. And even after the collapse of the Roman empire, which some have suggested might have been linked to lead poisoning, white lead remained fashionable. Its amazing covering power kept it in use as a cosmetic face powder for high society in the west and east alike. The iconic white face of Queen Elizabeth I was made up with a thick paste composed of white lead and vinegar which, over the years, was the likely cause of her death from blood poisoning. Large scale lead smelting returned with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution; lead crystal glass, ammunition, and Gutenberg's movable type printing press all required vast quantities of the stuff.  Metal type, as pioneered by Johannes Gutenberg. Photo: Bru-nO on pixabay. Jump forward to the 1920s, and the petrol additive tetra-ethyl lead, also known as just 'ethyl' or 'loony gas' made its appearance. This is another fascinating and tragic story in itself, suffice to say that this 'innovation' spread fine lead particles everywhere that roads exist, and well beyond. Sweet PoisonAnd it gets worse, because another highly unlikely property of lead salts is their sweetness. Honey aside, the Romans didn't have much in the way of sweeteners. Lead (II) acetate, also known as 'lead sugar', was a white crystalline powder made by boiling fruit juices in lead pots. It was used to sweeten wine and preserve fruits. As late as the 19th century, lead acetate was still added to cheap wines to make them more palatable, but eventually reliable testing methods appeared and the practice was stamped-out. However, high lead levels in Beethoven's hair suggest that this heavy wine drinker might have succumbed to Saturnism. The sweet nature of lead salts makes old, peeling paint especially dangerous to small children who often put things in their mouths. Pretty colours are enough of a temptation, but if it tastes good too...  A 1923 advertisement for Dutch Boy lead products, which was distributed alongside a colouring book encouraging children to join the (lead) party. Pervasive PoisonEven if you don't actually eat it, there are numerous pathways for lead to enter the body. According to UK government's health and safety sheet: “You can absorb lead when you breathe in lead dust or fumes. You can also swallow lead dust and debris, for example, if you eat, drink, smoke or bite your nails without washing your hands or face. Any lead you absorb will circulate in your blood. Your body gets rid of a small amount of lead each time you go to the toilet, but some will stay in your body, stored mainly in your bones. It can stay there for many years without making you ill.” That last part is perhaps good news for some of our more densely-boned sign painting colleagues. But without due care, more will enter the body, and old hands like Bob Dewhurst recall smoking cigarettes with paint on their hands, or "eating lunch or have a bag of potato chips and noticing that my fingertips were all clean!" Ruth Walton (@rw.handlettering) says that her “dad went to Cardiff art school in the 1960s and casually told me that another fine art student died of lead poisoning from her habit of licking her paintbrush.” Different WorldsIncreasing awareness of lead toxicity in northern Europe and the USA means acute lead poisoning is rare these days. It tends to mostly affect those involved with renovating old buildings, or people with hobbies that involve direct exposure, such as model soldier making, working with pottery glazes, lead soldering, or firearms use.  "Get the Lead Out" sketch by Noel B. Weber (@noelbweber). Some folk remedies remain a risk too, producing regular horror stories for the medical journals; red lead powder is undoubtedly an effective remedy for ringworm, but will probably kill the patient, too! Mark Oatis, founding Letterhead, shared an October 1930 article from the Sign Scene & Pictorial painters National Conference Journal: “It contained a handy tip, which extolled the use of tobacco (best chewed, rather than smoked) as a way to clear the head of dizziness, and all other deleterious effects of white lead exposure. Those fellows were hardy craftsmen, and they packed a parcel of grass roots learning (and a plug of chaw) into their colourful, poison-shortened careers.” Mark Gill remembers hearing a scary story on the radio many years ago about a house decorator. The man had presumably accumulated high levels from a lifetime's exposure to lead, and actually died of acute poisoning after getting an extra dose of paint in a shaving cut. Wikipedia's page on lead poisoning speculates that the painters Caravaggio, Goya and Van Gogh all had lead poisoning due to over exposure or carelessness when handling of white lead-based paints; “Caravaggio in particular is known to have exhibited violent behaviour, a symptom commonly associated with lead poisoning.” Chronic lead poisoning in adults is associated with violent crime rates, infertility, liver and kidney damage, and high blood pressure. In children, who absorb lead 4–5 times more easily than adults, any level of exposure will lead to learning and developmental difficulties. It is also considered a likely carcinogen and, anecdotally, Erik Skjolsvik (@erikskjolsvik) tells us that, “my dad was a painter in the 1950s and 60s. My sister would see him scoop lead powder with his hand and mix it in. He died aged 51 of all sorts of cancers.” Lead TodayWhen I started working on this article, I thought lead-based paint problems were a thing of the past. Wrong again. As testing methods improve, so does the scale of the problem. The World Health Organisation says that in March 2023 only half of the countries in the world enforce regulations concerning lead-based paints. The problem is massive, and on-going. Leaded paints for sale in the Philippines, and a sack of lead chromate in Vietnam. In the UK and northern Europe, lead-based paint is now only authorised for the restoration and maintenance of art works and historical buildings. In the USA, lead-based paint is still legal in certain industrial settings such as ship building and fine arts. However in India, for example, a kilo (2 lb) of white lead costs 600 rupees ($7.50), and 25 kg drums can be purchased. A lack of understanding about the accumulative dangers, plus its cheapness, continue to tempt many manufacturers to use lead-based paints instead of safer alternatives—buyers beware of brightly coloured imported toys for babies and dogs alike! ConclusionA tin of today's white lettering enamel will probably contain titanium dioxide pigment, binder and solvent. You might also find UV stabilisers, curing catalysts, emulsifiers, thickeners, surfactants, flow agents, and pigment stabilisers. By contrast, white lead paint had only two ingredients; white lead and linseed oil. The clear benefits of lead-based paints were that these ingredients were cheap, easy to find and together they formed a smooth, easily workable paint with excellent opacity. And the downside, being practically invisible, was/is just too easy to ignore. A last word to Bob Dewhurst: “I loved the stuff but I'm glad for my own survival it was removed.” Written by Jill Strong / @jill.strong.signs Thank you to everyone that contributed to this article with their memories, stories, and tragedies connected to the use of lead paint in signs and sign painting. And, in particular, Bob Dewhurst whose amazing stories made this a fun article to write. Further reading (if you dare)- 'A new study says the global toll of lead exposure is even worse than we thought', by Nicole Estvanik Taylor, NPR, November 2023.

- 'How Bangladesh removed lead from turmeric spice', by Kelsey Piper, Vox, September 2023.

More LearningMore History

|