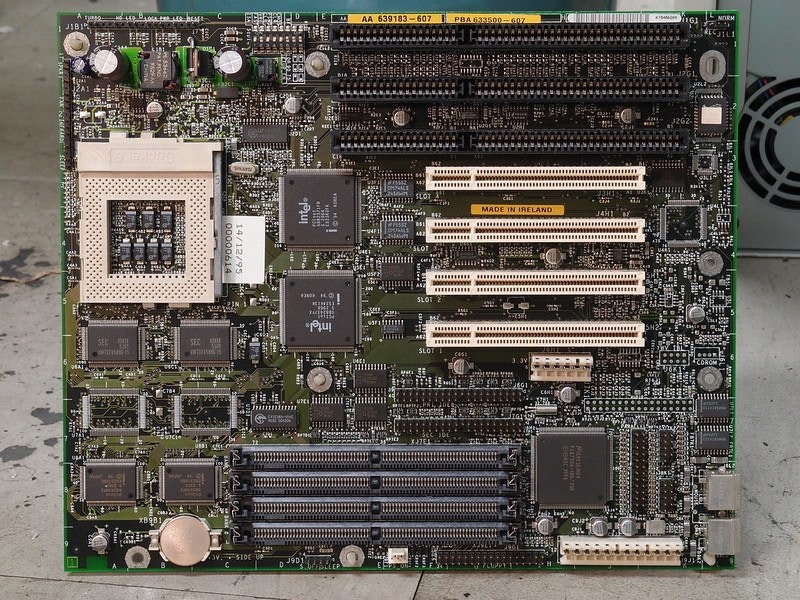

An Intel Pentium-era motherboard. Note the large PCI chipset in the middle of the board. (htomari/Flickr)

Intel had to crush a standards body on the way to giving us an essential technology

In the years before the Pentium chipset came out, there seemed to be some skepticism about whether Intel could maintain its status at the forefront of the desktop computing field.

On the low end, players like AMD and Cyrix were starting to shake their weight around. At the high end, workstation-level computing from the likes of Sun Microsystems, Silicon Graphics, and Digital Equipment Corporation suggested there wasn’t room for Intel in the long run. And laterally, the company suddenly found itself competing with a triple-thread of IBM, Motorola, and Apple, whose PowerPC chip was about to hit the market.

A Bloomberg piece from the period painted Intel in a corner between these various extremes:

If its rivals keep gaining, Intel could eventually lose ground all around.

This is no idle threat. Cyrix Corp. and Chips & Technologies Inc. have re-created--and improved--Intel's 386 without, they say, violating copyrights or patents. AMD has at least temporarily won the right in court to make 386 clones under a licensing deal that Intel canceled in 1985. In the past 12 months, AMD has won 40% of a market that since 1985 has given Intel $2 billion in profits and a $2.3 billion cash hoard. The 486 may suffer next. Intel has been cutting its prices faster than for any new chip in its history. And in mid-May, it chopped 50% more from one model after Cyrix announced a chip with some similar features. Although the average price of a 486 is still four times that of a 386, analysts say Intel's profits may grow less than 5% this year, to about $850 million.

Intel's chips face another challenge, too. Ebbing demand for personal computers has slowed innovation in advanced PCs. This has left a gap at the top--and most profitable--end of the desktop market that Sun, Hewlett-Packard Co., and other makers of powerful workstations are working to fill. Thanks to microprocessors based on a technology known as RISC, or reduced instruction-set computing, workstations have dazzling graphics and more oomph--handy for doing complex tasks and moving data faster over networks. And some are as cheap as high-end PCs. So the workstation makers are now making inroads among such PC buyers as stock traders, banks, and airlines.

This was a deep underestimation of Intel’s market position, it turned out. The company was actually well-positioned to shape the direction the industry went in through standardization. They had a direct say on what appeared on the motherboards of millions of computers, and that gave them impressive power to wield. If Intel didn’t want to support a given standard, there’s a chance said standard would be dead in the water.

Just ask the Video Electronics Standards Association, or VESA. The technical standards organization is perhaps best known today for its mounting system for computer monitors and its DisplayPort technology, but in the early 1990s, it was working on a video-focused successor to the Industry Standard Architecture (ISA), widely used in IBM PC clones. The standard, known as VESA Local Bus (VL-Bus), added support for the standards body’s then-emerging Super VGA initiative. It wasn’t a massive leap, more like a stopgap improvement on the way to better graphics.

And it looked like Intel was going to go for it. But there was one problem—Intel actually wasn’t feeling it, and Intel didn’t exactly make that point clear to the companies supporting the VESA standards body until it was too late for them to react.

Intel revealed its hand in an interesting way, according to San Francisco Examiner tech reporter Gina Smith:

Until now, virtually everyone expected VESA's so-called VL-Bus technology to be the standard for building local bus products. But just two weeks before VESA was planning to announce what it came up with, Intel floored the VESA local bus committee by saying it won't support the technology after all. In a letter sent to VESA local bus committee officials, Intel stated that supporting VESA's local bus technology "was no longer in Intel's best interest." And sources say it went on to suggest that VESA and Intel should work together to minimize the negative press impact that might arise from the decision.

Good luck, Intel. Because now that Intel plans to announce a competing group that includes hardware heavyweights like IBM, Compaq, NCR and DEC, customers and investors (and yes, the press) are going to wonder what in the world is going on.

Not surprisingly, the people who work for VESA are hurt, confused and angry. "It's a political nightmare. We're extremely surprised they're doing this," said Ron McCabe, chairman for the committee and a product manager at VESA member Tseng Labs. "We’ll still make money and Intel will still make money, but instead of one standard, there will now be two. And it's the customer who's going to get hurt in the end."

(For those familiar with video game history, you may recognize this general tactic from Nintendo’s infamous CD-ROM betrayal of Sony.)

But Intel saw an opportunity to put its imprint on the computing industry. That opportunity came in the form of PCI, a technology that the firm’s Intel Architecture Labs started developing around 1990, two years before the fateful screw-over of VESA. Essentially, Intel had been playing both sides on the standards front.

Why make such a hard shift, screwing over a trusted industry standards body out of nowhere? Well, essentially, beyond wanting to put its mark on the standard, it also saw an opportunity to build something more future-proof. As John R. Quinn wrote in PC Magazine in 1992:

Intel’s PCI bus specification requires more work on the part of peripheral chip-makers, but offers several theoretical advantages over the VL-Bus. In the first place, the specification allows up to ten peripherals to work on the PCI bus (including the PCI controller and an optional expansion-bus controller for ISA, EISA, or MCA). It, too, is limited to 33 MHz, but it allows the PCI controller to use a 32-bit or a 64-bit data connection to the CPU.

In addition, the PCI specification allows the CPU to run concurrently with bus-mastering peripherals—a necessary capability for future multimedia tasks. And the Intel approach allows a full burst mode for reads and writes (Intel's 486 only allows bursts on reads.)

Essentially, the PCI architecture is a CPU-to-local bus bridge with FIFO (first in, first out) buffers. Intel calls it an “intermediate” bus because it is designed to uncouple the CPU from the expansion bus while maintaining a 33MHz 32-bit path to peripheral devices. By taking this approach, the PCI controller makes it possible to queue writes and reads between the CPU and PCI peripherals. In theory, this would enable manufacturers to use a single motherboard design for several generations of CPUs. It also means more sophisticated controller logic is necessary for the PCI interface and peripheral chips.

To put that all another way, VESA came up with a slightly faster bus standard for the next generation of graphics cards, one just fast enough to meet the needs of 486 users. Intel came up with an interface designed to reshape the next decade of computing, one that it would even let its competitors use. This bus would even allow people to upgrade their processor across generations without needing to upgrade their motherboard. Intel brought a gun to a knife fight, and it made the whole debate about VL-Bus seem insignificant in short order.

The result was that, no matter how miffed the graphics folks were, Intel had consolidated power for itself by actually innovating and creating an open standard that would eventually win the next generation of computers. (It developed the standard, then gave away the patents. How nice of them.) Sure, Intel let other companies use the PCI standard, even companies like Apple that weren’t directly doing business with Intel on the CPU side of things at the time. But Intel, by pushing forth PCI, suddenly made itself relevant to the entire next generation of the computing industry in a way that ensured it would have a foothold in hardware, just as Microsoft dominated software. (Intel Inside was not limited to the processors, as it turned out.)

To be clear, Intel’s standards record wasn’t pristine. For example, its efforts to push forth a desktop video codec left many small companies miffed after the chip-maker randomly switched gears, per a 1993 New York Times article (which we’re linking, while noting our policy on linking the NYT). But its work with PCI definitely stuck.

Case in point: 32 years later, and three decades after PCI became a major consumer standard, we’re still using PCI derivatives in modern computing devices.