Our demand for cheap plastics is choking this town

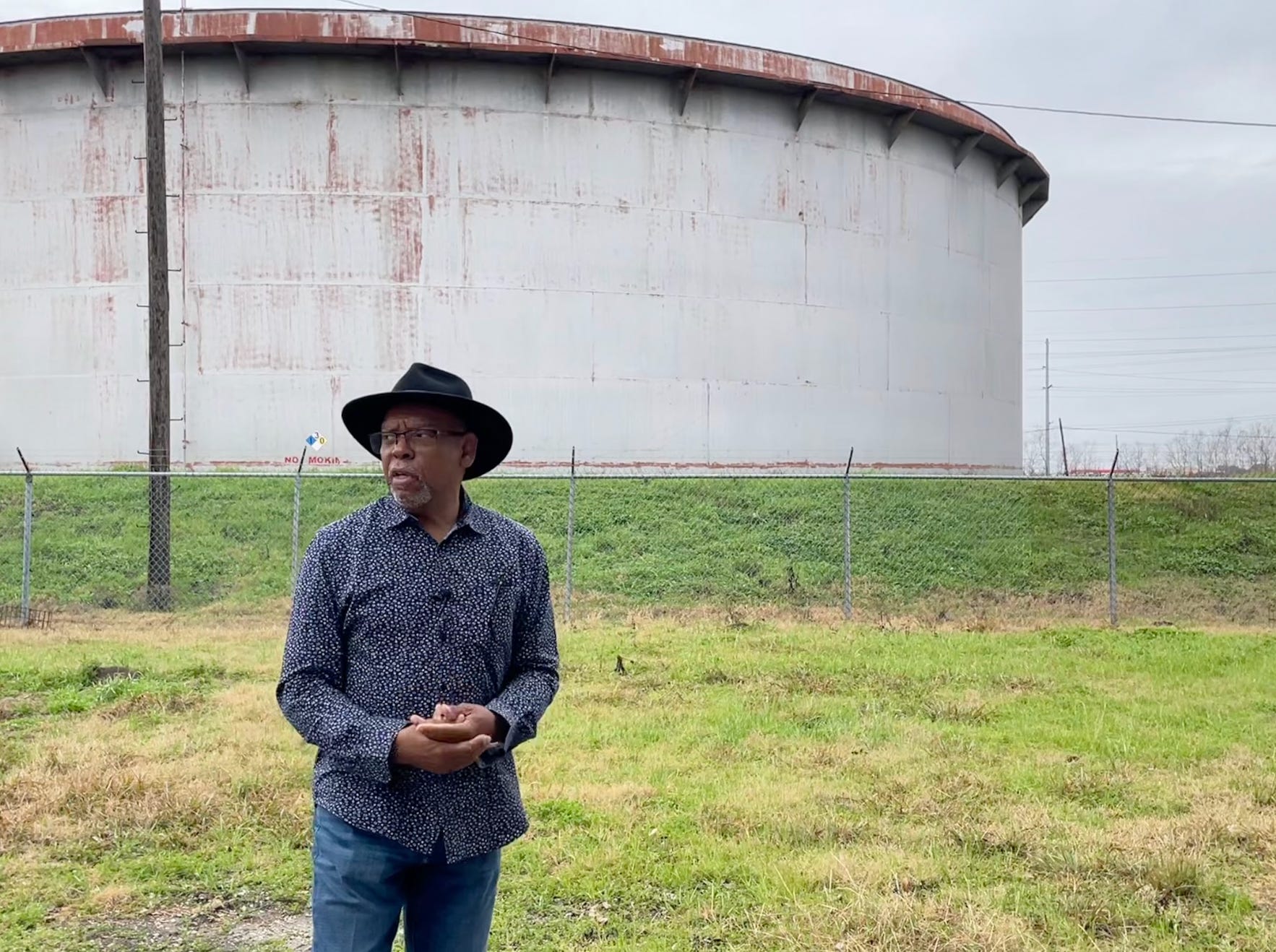

Welcome back to HEATED—Arielle here. This type of reporting is extremely valuable for reporters, readers, and the communities affected by pollution. But it’s also expensive to accomplish. So if you’d like to see more stories like this—and help us keep these stories free for everyone to read—please consider joining the small but mighty group of readers who funded this trip, and who fund all of our reporting. We promise to make it worth your while. Our demand for cheap plastics is choking this townArielle goes on a "toxic tour" of Port Arthur, Texas to experience the local impact of plastics: the fossil fuel industry's strategy to survive the clean energy transition.PORT ARTHUR, TX—John Beard Jr. stands in front of the largest refinery in North America, a beast of chrome shrouded in gray smoke. The day is overcast, and the smoke billowing from the Motiva refinery behind him mixes with the fumes from the Valero petrochemical plant across the street. Refineries stretch across the horizon as far as the eye can see—an unbroken line of pollution. After 38 years of working for Port Arthur’s booming fossil fuel industry, Beard knows exactly what is pouring out of those smokestacks. He tells the gaggle of reporters gathered around him to take a deep breath. “I won't promise you it won't harm you,” Beard says, describing the rotten egg smell of hydrogen sulfide, a carcinogenic chemical. “But you'll survive. I mean, we've done it for 120 years.”  A collection of images from Arielle's "Toxic Tour" of Port Arthur, Texas. Port Arthur, where Beard was born and raised, is ground zero for some of the worst pollution in the country. But it’s also where the fossil fuel industry is making its final stand against the energy transition, by betting on one of the most desirable and dirty products on Earth: plastic. The World Economic Forum predicts that plastic production will double in the next 20 years. This is why Beard has invited some 40 journalists to his hometown: to experience the impact of the fossil fuel industry’s strategy on frontline communities. Once an Exxon employee, Beard is now the founder of the Port Arthur Community Action Network (PA-CAN), a network he started to fight back against petrochemicals in his city. Beard takes us on a “toxic tour" of Port Arthur, population 56,000, where the welcome sign tells us we’re in “energy city.” The town is quiet on a Friday morning—we see hardly any people as we pass neighborhoods still bearing the scars from Hurricane Harvey. What we do see a lot of are refineries and plants, which are built so close to each other that we pull over every few minutes. Altogether, Port Arthur has 13 facilities, which sit next to schools, homes, and restaurants. Our first stop of the tour is Indorama’s Huntsman Petrochemical plant, which makes plastics. It shares a yard with a little league baseball field, and is next to a playground. “People have gotten used to it and accustomed to thinking there's no harm or danger,” he says. “But there's always imminent danger when you're dealing with fossil fuels and petrochemicals.” Beard knows intimately the dangers of working with petrochemicals, from his decades working in the ExxonMobil plant. Once during a safety training session, he says, a coworker vomited after inhaling too much benzene. That man was lucky, Beard tells me in an interview, because benzene can kill you. “Under high levels of exposure,” he says, “you may just pass out” and eventually die. Related reading: A chemical disaster occurred almost every day in 2023 He shows me photos of the sky outside his house, dark with clouds of smoke. That smoke carries toxic chemicals into the air like benzene, chloroform, formaldehyde, sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and butadiene. And every time a facility flares, or burns off excess gas, it is allowed to “accidentally” exceed the federal limit. Beard says he often wakes to the smell of rotten eggs, or tar-like creosote, or a slightly metallic odor. The Valero plant alone, which Beard can see from his kitchen window, has been accused of 600 air quality violations. The toxic chemicals from the petrochemical plants spike cancer rates and other illnesses. People living in Jefferson County, which includes Port Arthur, have a cancer rate 18 percent higher than the average Texan, according to the Texas Cancer Registry’s most recent data. A study by the University of Texas Medical Branch found that people who lived near Port Arthur refineries were more likely to have heart and respiratory conditions, nervous system disorders, skin disorders, and headaches. Another study, published in the Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, found that nonwhite refinery workers in Port Arthur were more likely to die from cancer. If the fossil fuel companies can’t operate “in a way that doesn't threaten the lives and health of people, then they shouldn't do it at all,” says Beard, as we sit in an empty Holiday Inn dining room that once held emergency meetings for Hurricane Harvey. “We shouldn't have to suffer and breathe polluted air because they want to make money.”  Port Arthur’s modest 144 square miles is worth hundreds of billions of dollars to the fossil fuel industry. And its fastest growing sector is not oil and gas, but plastic. Most plastics today are made from ethane, a byproduct of fracking. Ethane “crackers” use steam to crack ethane molecules into the ingredients for plastic, including ethylene, propylene, and butadiene. Those plastics make everything from food packaging to footballs. In Port Arthur, making plastic is even cheaper than elsewhere, because the refineries that supply fossil fuels to the ethane crackers sit conveniently next to them. The global plastics market was worth $712 billion in 2023, and is still growing rapidly. Plastic consumption is expected to nearly triple by 2060, according to the OECD. That makes plastics, and the petrochemicals that make them, a second chance for a fossil fuel industry that is slowly being phased out. “Petrochemicals are the side hustle of the oil and gas industry, but they’re trying to make it their main hustle,” said Heather McTeer Toney, an activist with Beyond Petrochemicals, which organized the conference. But in order to make sure their petrochemical side hustle is successful, the fossil fuel industry needs a social license to operate. To achieve that social license, the industry has been busily selling the public on the necessity of plastics to our way of life. Fossil fuel-funded groups have created educational materials for schoolchildren and national commercials highlighting how hospitals can’t function without plastic. Last year, major oil and gas companies sent representatives to the U.N.’s conference on ending plastic pollution to push the message that recycling can solve the problem (it can’t). In the communities where they build their plants, global conglomerates like Valero, Exxon, and Chevron buy community goodwill by promising jobs. Beard says that when they first come into town, the oil and gas companies promise jobs to residents. But those jobs rarely materialize. Port Arthur’s unemployment rate has remained one of the highest in the country for years, while polluting industries have proliferated. This pollution is concentrated in a handful of neighborhoods that are predominantly low income or communities of color. Eighteen communities, including Port Arthur, bear more than 90 percent of all plastic climate pollution reported to the EPA. More than 50 percent of Port Arthur residents are Black or Latino; almost one-third of residents live below the federal poverty line. “They build the [refineries] in communities of color or poor people because they have little ability to fight back,” Beard said. “They don't have money for lawyers, and most of them don't even understand and know what it is they’re breathing in.” Beard tells me that while working at Exxon, it was common for plant workers to die from disease before they got a chance to retire. His family, who have worked in the refineries for three generations, have also gotten sick. “I got family members that have migraine headaches, nosebleeds,” he said. “One of my children had to have a benign tumor removed.” Thinking about his children and his grandchildren's future is what spurred Beard to take on the industry that is the only major employer in town. And part of his strategy is inviting reporters, politicians, and EPA officials to Port Arthur and reminding them that plastic pollution doesn’t stop in frontline communities. The wind doesn’t respect a fence line, he tells the tour group. But the truth that Beard already knows is, unlike the people who actually live in Port Arthur, the journalists recording his words will go home to cleaner air at the end of the conference. As he takes us through another neighborhood with oil tanks in its backyard, he anticipates the question outsiders usually ask him: if the pollution is so bad here, why do people stay? “This is where you're born, and it's where you raise your family in the house that your grandparents had,” he says. “Why would you move and have to start over?” Activists fighting against plasticsIn order to reduce petrochemical pollution, activists say changes in plastic regulation are needed. Eliminating single-use plastics, plastic packaging, and chemical recycling are a start.

Know of other activist efforts to fight plastic and petrochemical pollution that we missed? Let each other know in the comments! Catch of the Day: Hi all—Emily here. If you read last week’s newsletter, you know that my family has been preparing to rehome our golden retriever, Mason, due to my mom’s recent hip replacement surgery. I’m both very happy and still a little sad to report that Mason is now safely and happily with his new family, and they have been graciously sending us pictures and videos of Mason’s new fun-filled life! Here’s him playing with one of the neighbor’s dogs in the closed-down community garden. As for my mom, she’s doing well! She came home from the hospital on Saturday, and it’s been all physical therapy assisting/medication scheduling/shower bar installing ever since. We even went on a (very slow, equipment-assisted) walk outside today. Thank you all so much for your kind words and support. They’re really helping us get through it! Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy HEATED, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Older messages

A note from Emily

Wednesday, February 21, 2024

Why we won't be publishing this week. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

There's no such thing as a “climate-friendly” Super Bowl

Tuesday, February 13, 2024

Plus, a round-up of climate highlights from the game. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

“The Daily” runs a greenwashing BP ad

Tuesday, February 6, 2024

The Daily promised to end fossil fuel sponsorships in 2021. BP promised to stop “corporate reputation advertising” in 2020.

Understanding Biden's LNG decision

Thursday, February 1, 2024

There's a lot of politically-motivated misinformation floating around about it. Here's what's really happening.

“These streets should be paved with gold”

Tuesday, January 30, 2024

How a decade-long refinery worker became an anti-LNG campaigner

You Might Also Like

Hit the Courts This Spring in Our Favorite Tennis Shoes

Saturday, March 1, 2025

If you have trouble reading this message, view it in a browser. Men's Health The Check Out Welcome to The Check Out, our newsletter that gives you a deeper look at some of our editors' favorite

"I Might Not Be Getting Anything Done, But At Least I'm Not Having Fun"

Saturday, March 1, 2025

Do Americans actually resist pleasure? ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

“Fog” by Emma Lazarus

Saturday, March 1, 2025

Light silken curtain, colorless and soft, / Dreamlike before me floating! ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

savourites 96

Saturday, March 1, 2025

escaping the city | abandoning my phone | olive oil ice cream ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

5-Bullet Friday — How to Choose Peace of Mind Over Productivity, Guinean Beats for Winding Down, Lessons from Legendary Coach Raveling, and a New Chapter from THE NO BOOK

Saturday, March 1, 2025

"Easy, relaxed, breathing always leads to surprise: at how centred we already are, how unhurried we are underneath it all." — David Whyte ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Nicole Kidman's “Butter Biscuit” Hair Transformation Is A Perfect Color Refresh

Saturday, March 1, 2025

Just in time for spring. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 2.28.2025 Nicole Kidman's “Butter Biscuit” Hair Transformation Is A Perfect Color Refresh (Celebrity) Nicole Kidman's “Butter

David Beckham's Lifestyle Keeps Him Shredded at 50

Friday, February 28, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE David Beckham's Lifestyle Keeps Him Shredded at 50 David Beckham's Lifestyle Keeps Him Shredded at 50 The soccer legend opens up

7 Home Upgrades That Require Zero Tools

Friday, February 28, 2025

Skype Is Dead. There are plenty of ways to make quick improvements to your house without a single hammer or screwdriver. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED

Heidi Klum Matched Her Red Thong To Her Shoes Like A Total Pro

Friday, February 28, 2025

Plus, the benefits of "brain flossing," your daily horoscope, and more. Feb. 28, 2025 Bustle Daily Here's every zodiac sign's horoscope for March 2025. ASTROLOGY Here's Your March

How Trans Teens Are Dealing With Trump 2.0, in Their Words

Friday, February 28, 2025

Today in style, self, culture, and power. The Cut February 28, 2025 POWER How Trans Teens Are Dealing With Trump 2.0, in Their Words “Being called your correct name and pronouns can be the difference