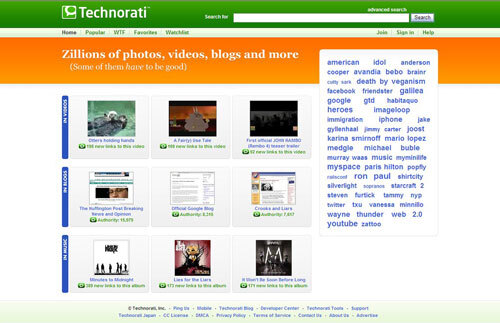

Technorati, as the site appeared in 2007. (buou/Flickr)

The early blogosphere was defined by side projects that became businesses. Technorati was one of those.

When it comes down to it, blogging has always been shorthand for a way to describe conversational writing on the internet, though the specific terminology took a while to find its footing. Some early blogging notables, like late science-fiction author and Byte columnist Jerry Pournelle, were slow to embrace the term.

But it ultimately took off, in no small part thanks to a series of small startups that were generally passionate about the idea. Perhaps the most famous was Blogger, a platform notably created by Evan Williams and Meg Hourihan in 1999 under the Pyra Labs brand. Hourihan notably developed the Kinja blogging platform used by Gawker Media-descendant sites even today; Williams, of course, is a cofounder of Twitter and Medium.

Small startups like Pyra Labs were the lifeblood of early blogging, and played a fundamental role in helping to set the parameters of early internet culture as it evolved from the excesses of Web 1.0 (think Kozmo and Pets.com) into what became known as Web 2.0. South by Southwest’s interactive portion gained much of its modern cultural cachet in large part because Williams and other bloggers decided to embrace it.

It was not a particularly stable time for the web, admittedly. Infamously, Pyra Labs, which did not have a business model for Blogger as the company was intended to develop project management software, saw its staff members leave one-by-one as its funding dried up, leaving Williams as its only employee.

And years later, many of the ideas invented around this time got swallowed up into the walled gardens of the startups and corporate giants that followed these digital pioneers.

One of those digital pioneers was a guy named David Sifry. A blogger himself, he wanted a way to better understand how his own site was doing on the internet. So he built a way to do that. Somewhat similarly to Pyra Labs, the tool that he built, which he called Technorati, was not necessarily intended to be a business. He already had a startup that he was working at, which focused on wireless computing.

“Essentially, it is a site that creates a set of web services that I’ve always wanted for myself—services layered on top of the wealth of current search functionality and tools available for bloggers,” he wrote in a 2002 blog post.

Among those features were a number of basic tools that told users who was writing about or linking to a blog post, how your site rates in relation to specific Google search terms, historical information on how sites are ranking over time, and—most importantly—where everyone ranked.

The ranking element effectively made it a search engine for blogs, a great way to find new voices at a time when the “blogosphere” was a new and vibrant thing. And rather than grabbing this data only occasionally, as many search engines did at the time, it was built around the pulse of the digital ecosystem. Effectively, it filled an immediacy gap for blogs that early search engines were not designed for.

But the data it offered bloggers might have been the most important part of its reason for being.

These days, companies charge hundreds or thousands of dollars a month for the kinds of analytics Technorati generated. Sifry was charging $5 per year for access to historical information on Technorati. This was before we had Google Analytics or anything similar, so this added data was a big deal.

At first, Technorati was a side project for Sifry, just like Blogger was for Pyra Labs. But the cultural tide quickly changed things and made Technorati hugely valuable to large companies. In its first year online, it wasn’t just small-scale bloggers that were interested in the data Sifry had gathered, but major news outlets such as The New York Times and Reuters. As Inc. reported in 2006, Sifry was soon signing a deal to license his technology to AOL—and quitting his job to make Technorati a full-time thing.

Technorati swag, circa 2005. (Nikita Kashner/Flickr)

And, just like blogging itself, Technorati grew fast. To give you an idea, the company scored an impressive partnership with CNN tied to the 2004 Democratic National Convention. Sifry found himself blogging and reporting for CNN, rounding up a variety of voices that Technorati was well-positioned to highlight.

“I hope that this helps people in the living room realize that they can be participants,” Sifry said, according to PR Week.

Not bad for a company that less than two years before was a weekend project for Sifry.

Blogger and Technorati were two of the earliest Web 2.0 tools, predating Friendster, Facebook, MySpace, Digg, Reddit, and numerous other mid-2000s icons of blogging and social media.

At the center of this trend was the concept of the blog, which encouraged people to own their own piece of the internet. Many of the later Web 2.0 tools focused on trying to get people to spend as much time as possible within their URL; Technorati, meanwhile, was really focused on helping this universe of bloggers become better at blogging.

Other services that mined this territory, like Popdex and the Mark Cuban-backed IceRocket, played an important role in the rise of the blog-targeted search engine, whether by ranking the most popular sites or by making it easier to track information in real time. (After all, new posts from amateur pundits were always filtering in.) But none cast a shadow quite as large as that of Technorati, whose ranking system meant something for bloggers. To appear on the list, particularly in a high spot, was a sign of validation. Yes, you were good enough at blogging.

It was only a matter of time before bigger players intruded on Technorati’s territory. And yes, when I say “bigger players,” I mean Google.