|

I’m Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.” Are you new here? Get free emails to your inbox daily. Would you rather listen? You can find our podcast here.

Today's read: 12 minutes.🇭🇹 The current violence in Haiti, and a brief dive into the nation's history — and its relationship with the United States.

Just a few tickets left!We sold out our General Admission tickets (again) for our live event on April 17 in New York City, but a limited number of VIP tickets remain. The VIP experience gets you a piece of Tangle Live merchandise, a small group discussion with me (Isaac) after the show, and one of the best seats in the house. We’d love to see you there — get your tickets here before we sell those out, too!

Quick hits.- The Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore collapsed early this morning after it was struck by a large cargo vessel. A search effort is underway to find six construction workers who were on the bridge when it was hit. (The collision)

- The judge presiding over Donald Trump's hush money case in New York City scheduled the trial to begin on April 15, denying multiple appeals from Trump’s attorneys to delay the start of the trial. (The decision) Separately, a New York appeals court said it would pause the enforcement of the $464 million judgment in the fraud case against Trump and the Trump Organization if they post a $175 million bond within 10 days. (The ruling)

- The Supreme Court is hearing oral arguments today to decide whether to restrict access to mifepristone, a widely used abortion drug. (The case)

- Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) signed a law that would prohibit anyone 14 years old and younger from having a social media account. (The bill)

- The U.S. Department of Justice charged seven hackers it alleges have worked on behalf of the Chinese government to target thousands of U.S. and international individuals and companies. (The charges)

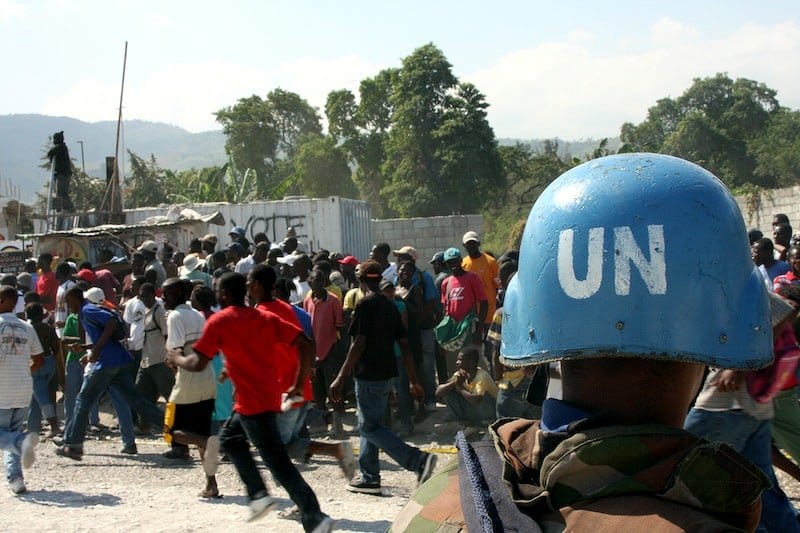

Today's topic. Violence and unrest in Haiti. Over the past week, more than 230 U.S. citizens have been evacuated from Haiti as a gang-led rebellion continues to surge through the Caribbean nation. In a briefing last Monday, March 18, U.S. State Department Spokesperson Vedant Patel called the situation “one of the most dire humanitarian situations in the world,” saying that "gang violence continues to make the security situation in Haiti untenable, and it is a region that demands our attention.” On Sunday, 30 U.S. citizens were evacuated from Haiti to Miami aboard a charter flight. Over 1,600 Americans have filled out crisis intake forms at the U.S. Embassy in Haiti. Back up: On the evening of March 3, gangs in Haiti stormed a major prison in the capital Port-au-Prince, freeing 3,700 inmates and leading the government to declare a state of emergency. The prison attacks followed calls by gang leader Jimmy Chérizier to overthrow President Ariel Henry, who came to office shortly after the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021. Henry had pledged to step down by early February 2024, but later said that security must be re-established before Haiti could hold free and fair elections. The clashes began while Henry was in Kenya finalizing the details of a UN-sponsored mission to contract 1,000 police officers to help Haiti’s security situation. Gang violence has led to the displacement of over 362,000 people in recent years and over 15,000 people since February, according to U.N. estimates. Gangs have continued to launch attacks across the nation’s capital, but violence has eased intermittently since Henry announced that he intends to resign. The history: The U.S. and Haiti have a centuries-old relationship. After enslaved Haitians rebelled against their French rulers in the late 18th century (the largest successful slave revolt in history), Haiti was isolated by the U.S. on the world stage while enduring harsh economic conditions imposed by President Thomas Jefferson. Later, in 1915, the U.S. sent troops into Haiti following the assassination of President Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam. The occupation lasted from 1915-1934, and the U.S. continued to control Haiti's public finances until 1947. U.S. Marines were also sent into Haiti in the aftermath of a violent coup in 2004. More recently, the U.S. has attempted to support Haiti in the wake of multiple natural disasters, though those efforts have yielded mixed results. After a catastrophic earthquake in 2010, the American Red Cross raised nearly $500 million to help Haiti rebuild, but later investigations found the vast majority of that money went unaccounted for or was appropriated for internal use. What now? CARICOM, a transnational trade group of Caribbean nations, has been meeting with officials from France, Canada, and the United States to establish a nine-member transitional council to choose Haiti’s next leader. The council’s formation has been delayed by the continued violence in Haiti, including death threats to party leaders who would comprise the council. Last week, the State Department circulated a document among lawmakers outlining the operation of a “Multinational Security Mission” to Haiti. However, the plan does not define key details of the potential operation, including how international forces would help local police quell gangs. Further, Republican lawmakers have signaled they are unlikely to support congressional funding for the force until a more complete plan is produced. “The human suffering and devolving crisis in Haiti is tragic,” Sen. Jim Risch (R-ID) said in a joint statement with Rep. Michael McCaul (R-TX) last week. “Yet, after years of discussions, repeated requests for information and providing partial funding to help them plan, the administration only this afternoon sent us a rough plan to address this crisis.” House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) called on Republican leaders to release $50 million in security support for Haiti. “The situation on the ground in Haiti has rapidly deteriorated while House Republicans have refused to deliver the resources necessary to carry out this mission,” Jeffries said. Today, we’re going to explore arguments about what role the U.S. should play in addressing Haiti’s current crisis, with perspectives from the right, left, and abroad. Then, my take.

What the right is saying.- The right favors a non-interventionist approach to the crisis, suggesting Biden’s current plan will only worsen the situation.

- Others point to the history of U.S.-Haiti relations as evidence that further American involvement won’t help the Haitian people.

In Fox News, Andrés Martínez-Fernández wrote “Biden is desperate to help Haiti. But he's doing it all wrong.” “After consistently failing to address the years-long crisis that was clearly in motion, Democrats’ slapdash effort to ‘do something’ in Haiti is now gaining steam in Washington and threatens to not only deepen the crisis in the Caribbean but also to entrench the United States in yet another dangerous international quagmire,” Martínez-Fernández said. “It is perhaps the height of U.S. weakness under the Biden administration that we are turning to Kenya to confront crises within our own hemisphere. But beyond the shame such a strategy heaps on the United States, the muddled effort is highly likely to backfire.” “It’s clear that the U.S. should not repeat the mistakes of the past and send in the military to Haiti every couple of decades to restore a corrupt elite to power. The notion of having African forces do the job instead is also dubious,” Martínez-Fernández wrote. “The U.S. must also ensure it is prepared to confront a looming wave of mass migration from Haiti… The first step here is for the Biden administration to immediately end its permissive policies toward illegal immigration and secure the U.S. border.” In The American Conservative, Connor Echols argued “the U.S. should let Haitians decide their own future.” “In a world wracked by crises, the U.S. has little to gain by imposing a half-baked plan on a country that has long opposed American intervention in its internal politics,” Echols said. “The best path forward is far simpler. As was the case in Afghanistan, the U.S. can best serve Haiti by taking a step back and allowing Haitians to decide their own future. As Jake Johnston—a Haiti expert at the Center for Economic and Policy Research—recently told me, the tortured history of U.S.-Haitian relations leaves no other choice.” “Conversations about Haiti tend to focus on images of chaos and poverty, but few Americans ask where that chaos comes from. In reality, much of Haiti’s current woes stem from shoddy, short-sighted U.S. policy. Over the past century, consecutive American governments have posed as the island nation’s savior only to undermine its hopes for democracy at every turn,” Echols wrote. “This history leads to an inescapable conclusion: When Washington puts its finger on the scales of Haitian politics, chaos ensues.”

What the left is saying.- The left calls for a safe haven in the U.S. for Haitian refugees.

- Others say Haiti needs foreign assistance to establish a sustainable government.

The New York Daily News editorial board said “we can and should protect those forced to flee.” “Haitians need a committed civil society to remain and reconstruct, but it is also perfectly understandable that some people who simply want to live in stability and quietude would leave, just as some Americans would decamp if our society collapsed into internecine violence,” the board wrote. “While we may intuitively understand the reasons that make regular life untenable for some, this understanding tends to break down when they actually show up asking for help.” “Does this mean the U.S. needs to accommodate every person from around the globe suffering under persistent violence and instability? Not really, but our principles and own economic interest should dictate that we work to accommodate as many as we can,” the board added. “The federal government should work to expand the existing refugee system in places like Haiti and Ecuador, with moments of acute need, and make greater use of existing executive tools like temporary protected status.” In The Chicago Tribune, Elizabeth Shackelford wrote “Haiti can’t right itself without restoring security — and a working government.” “There are no quick fixes, but some paths to peace are more promising than others. If Haiti and its international partners can learn from past mistakes, Haiti’s inevitably long road ahead could provide a sustainable foundation for a better future. That’s a big ‘if,’ though,” Shackelford said. “Haiti faces two distinct but related crises: widespread insecurity and a broken political system. For that reason, the deterioration in Haiti often brings comparisons to Somalia. As a U.S. diplomat who served in the latter, I can offer this lesson: Security gains will remain fleeting in the absence of inclusive, effective governance.” “The hard part begins once that government is in place, though. Its legitimacy will be judged not only by who it appears to represent but also by its performance. Specifically, it will be judged by whether or not it can return security to the country. Elections are nice, but they probably aren’t as important to the people of Haiti today as their families’ safety. Ultimately, it will be judged on whether it can provide the essential services that Haitians today lack.”

What international writers are saying.- Some writers in Haiti say the country’s leaders must take ownership of their role in the country’s collapse.

- Other writers from abroad point to centuries of exploitation as the driving force behind Haitians’ plight.

In The Haitian Times, Macollvie J. Neel said “quit the blame game and focus on ending the bloodshed.” “Yes, we can blame the march of Western imperialism and neocolonialism across the 19th and 20th centuries for Haiti’s false start toward democracy. These ’isms allowed repressive regimes to rise to facilitate hegemonic U.S. interests. Yet, Haiti cemented its place in the canon of liberation movements across these eras – from abolition, negritude and pan-Africanism to anti-apartheid and Black Lives Matter. That achievement won’t change no matter who helps Haiti now or how they do it. We can still rock our 1804 hoodies for another 220 years. “But here’s the thing: Cultural pride and political neighbor-shaming don’t stop stray bullets from striking people in their beds. They don’t compel goons to cease raping and pillaging, displacing families, or triggering suicides. Rather, they feed the ‘Haiti in crisis’ story, turning it into a gawk-inducing sideshow in the midst of world affairs,” Neel wrote. “All this points to a reason for Haitians to expect and ask for what the world should and can give at this moment: an armed rescue mission.” In The Guardian, Kenan Malik wrote “plundered and corrupted for 200 years, Haiti was doomed to end in anarchy.” “To make sense of the latest events, we need to understand not just where Haiti is today, but also how it got there,” Malik said. “The history of Haiti is one in which the nation’s governing classes have exhibited a contempt for the masses extraordinary even by the standards of the global south. It is also one in which foreign powers have never shrunk from repression and bloodshed, or straightforward theft, in pursuit of their aims, sometimes in alliance with local elites, sometimes in opposition to them.” “The tragedy of Haiti is not just the devastation wrought on its people but also that, while today it may be a symbol of corruption and lawlessness, 200 years ago it symbolised, indeed was the living embodiment of, the opposite: the possibilities of human emancipation,” Malik wrote. “The tragedy is that the opposite has happened, that the people of Haiti remain excluded from the governance of their country. Until that changes, Haiti will not change.”

My take.Reminder: "My take" is a section where I give myself space to share my own personal opinion. If you have feedback, criticism, or compliments, don't unsubscribe. Write in by replying to this email, or leave a comment. - To understand how Haiti got here, it’s vital to understand its historical relationship with the U.S. and Europe.

- Colonialism and exploitation are driving forces behind Haiti’s perpetual instability, but they don’t tell the whole story.

- The U.S. is faced with three flawed options for how to address the crisis: Do nothing, broker peace alongside allies, or stage a military intervention.

This is a terrible situation with no good way out. It’s been so long since Haiti’s last election that its parliament does not have enough current members to hold a vote; its current president, who was appointed after its last elected president was assassinated, has been feckless against powerful gangs throughout his term; it has no standing army, a depleted police force, and no faith in its government. Now, hundreds of thousands have been displaced, and mass famine threatens the lives of millions of Haitians. As many commentators have said, Haiti’s disarray is a seemingly permanent state. To understand why, it’s necessary to get a better understanding of Haiti’s history, which is one of the bloodiest and most traumatized of any country in the world. It’s impossible to sum it all up in just a few paragraphs, but here are a few major events: Immediately after Haiti’s successful rebellion in 1791, Haiti was effectively embargoed by Spain, France, and the newfound United States. To allow it to enter the global economy, the French — struggling for funds after its own republican revolution — demanded Haiti pay reparations for the lives of the slave owners killed in its revolt. Haiti had little choice but to give in, agreeing to pay more than its annual GDP to France every year. To get the funds it needed to pay France back, France offered Haiti a loan, which it also had to pay back — with interest. These payments are called Haiti’s “double debt.” In 1915, Haiti’s president was assassinated, prompting the United States to occupy the country to help stabilize it. The U.S. installed a government, plundered Haiti’s treasury, and withdrew 15 years later following a series of uprisings. The U.S. intervened again in the 1990s, to depose a dictator who overthrew then-president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Does colonialism, isolation, and exploitation fully explain Haiti’s current situation? No, but it does begin to explain it — and it does explain the nation’s deep-seated and understandable distrust of foreign intervention. More recently, in 2010, Haiti was rocked by a deadly earthquake, which left it in desperate need of aid. Not only did some of that aid go missing, but the U.N. also accidentally caused a deadly cholera outbreak when it established a camp upstream of Haiti’s main water source. The earthquake also destroyed the presidential palace, which, symbolically, still has not been rebuilt. There are many things in Haiti’s past that could, and should, have gone differently. But they didn’t. So, what could the U.S do now, and what should it do? As I see it, there are three main options: Solution one: Do nothing. As many commentators have suggested, Haiti’s problems must be solved by Haiti. The long history of devastating foreign intervention has not only made Haitians mistrustful of the U.S, but U.S. citizens mistrustful of its own involvement. We’ve seen how our involvement in Afghanistan in recent decades seems to have just made the situation worse, and cost us billions of dollars and thousands of lives. We should just stay out of it. The problem: Without the international help Haitians have been screaming for, it’s likely that Haiti’s situation will devolve further. Gang leader Jimmy "Barbecue" Chérizier united rival factions in response to President Henry’s attempts to secure a police force from Kenya. That concerted opposition tells us that such a force would probably be effective. It also tells us that power vacuums, like the one caused by Henry’s absence, create ideal situations for violent disorder to thrive. And if disorder does thrive, it will cause an enormous refugee crisis. We should want to help Haiti not just for humanitarian reasons, but because our already straining resources on our border will buckle under the weight of an unimaginable migrant crisis if the anarchy in Haiti continues. Solution two: Intervene through international consensus. CARICOM has already started the process of organizing the nine-member counsel to choose Haiti’s next president, and leaving that process in the hands of a regional cooperative makes the most sense. We should help the U.N. organize the police force from Kenya and other countries, we should help CARICOM usher in the next government, and we should help international groups fund the next stage of Haiti’s rebuild. The problem: The biggest issue with this plan is the subtext: Any future government that is arrived at through peaceful consensus of Haitian politicians and power players will have to include Chérizer and the gangsters, who essentially have a gun to the head of the political process on the ground. As Kenan Malik wrote (under “What international voices are saying”), Haiti has been plagued by corruption within its ruling and elite classes. Ushering Henry out the door only ushers more of those corrupt leaders in. Solution three: Fully intervene. The level of corruption in Haiti is total, the police force is outgunned, and the army is non-existent. The arable land in Haiti has been depleted from decades of poor usage rights enforcement, and before that by centuries of aggressive colonial sugar and coffee harvesting. Haiti isn’t becoming a failed state — it already is one. If the Haitian people have any hope of surviving, its state must be rebuilt. We should come in with a military force, establish law and order, rout Chérizer and the gangs, and help Haiti actually build its country back. The problem: First, it’s almost politically unthinkable. The U.S. has no appetite for nation-building, and Biden authorizing a U.S.-led and years-long occupation before a presidential election is unimaginable. And for good reason. Putting U.S. boots on the ground in Haiti would mean engaging in urban warfare against the gangs, then installing a friendly regime… which starts to sound eerily familiar. Why would we expect a military intervention in Haiti — a country with a very valid list of reasons to distrust foreign occupations — to be any better this time? What do I recommend? This is one of those days where I don’t mind saying I honestly don’t know. As I wrote out the pros and cons of each strategy, I found myself more convinced by the reasons not to pursue each one. Doing nothing and enabling a refugee crisis of historic proportions is unthinkable, validating a brutal gang leader and entrenching Haitian corruption is unthinkable, and a full U.S. intervention of Haiti is unthinkable. In my opinion, of all the bad options, a full military occupation sounds like the worst choice — but I don’t have much more to offer beyond that. In the short term, the best we can do is whatever eases the violence and allows some humanitarian relief to flow to the millions of Haitians in need. In the long term, I have no satisfying answer. The best I can say is that we should all pray for the safety of the many innocents in Haiti, try to educate ourselves on the situation, and hope our political leaders have a more creative solution than I do. Take the poll: What do you think should be the U.S. response to the crisis in Haiti? Let us know! Disagree? That's okay. My opinion is just one of many. Write in and let us know why, and we'll consider publishing your feedback.

Help share Tangle.I'm a firm believer that our politics would be a little bit better if everyone were reading balanced news that allows room for debate, disagreement, and multiple perspectives. If you can take 15 seconds to share Tangle with a few friends I'd really appreciate it — just click the button below and pick some people to email it to!

Your questions, answered.We're skipping the reader question today to give our main story some extra space. Want to have a question answered in the newsletter? You can reply to this email (it goes straight to my inbox) or fill out this form. Want to have a question answered in the newsletter? You can reply to this email (it goes straight to my inbox) or fill out this form.

Under the radar.Boeing’s troubled 2024 continued this week with the news that the aircraft company’s CEO, Dave Calhoun, will step down at the end of the year as part of a leadership shakeup that includes the head of Boeing’s commercial aircraft unit. Though Calhoun framed his decision to step down as part of a deliberate succession plan, Boeing’s board had voted in 2021 to raise the company’s mandatory retirement age to enable him to serve as CEO until 2028. Although no fatal crashes involving Boeing aircraft have occurred during Calhoun’s tenure, a recent spate of near-disasters — most notably a panel flying off a Boeing 737 Max 9 plane during an Alaska Airlines flight in January — have prompted renewed scrutiny of the company’s commitment to safety and production quality. The New York Times has the story on the leadership changes, and Fortune has the story on the company culture that foreshadowed Boeing’s safety crisis.

Numbers.- 11.5 million. The approximate population of Haiti.

- 5.0 million. The approximate number of Haitians currently facing crisis levels of food insecurity or worse.

- 5%. The percentage of Haitians who received humanitarian food aid intended for them between August and December 2023, according to a new report from the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification.

- 80%. The percentage of Port-au-Prince that is controlled by gangs, according to UN estimates.

- $7,400. The Dominican Republic’s approximate GDP per capita in 2002.

- $2,200. Haiti’s approximate GDP per capita in 2002.

- $24,100. The Dominican Republic’s approximate GDP per capita in 2022.

- $3,200. Haiti’s approximate GDP per capita in 2022.

Thursday’s poll: 997 readers took our poll on the terrorist attack in Moscow with 97% saying they thought ISIS was responsible. Most of those who disagreed suspected Putin’s involvement somehow. “Putin has created the kill or be killed environment,” one respondent said. What do you think should be the U.S. response to the crisis in Haiti? Let us know!

Have a nice day.Every morning, 50-100 people line up in front of a new kind of recycling center owned by the municipality of Aarhus, the second-largest city in Denmark. Instead of discarding items for its material to be used, Danes go to the center, called Reuse, to give — and take — all sorts of items for free. The project started in 2015 when Kredsløb, a company owned by the city, decided to try to reduce the amount Aarhus citizens were throwing away. Now, more than two metrics tons of objects from dishes to computers move through the Reuse center every day, from one person to another. “You take something that wasn’t worth anything and add value to it just by picking it up. This idea is maybe the key or the cornerstone of what Reuse is to me,” explains Lasse Andersen, a Reuse regular of about four years. Reasons to be Cheerful has the story.

Don't forget... 📣 Share Tangle on Twitter here, Facebook here, or LinkedIn here. 🎥 Follow us on Instagram here or subscribe to our YouTube channel here 💵 If you like our newsletter, drop some love in our tip jar. 🎉 Want to reach 97,000+ people? Fill out this form to advertise with us. 📫 Forward this to a friend and tell them to subscribe (hint: it's here). 🛍 Love clothes, stickers and mugs? Go to our merch store!

|