|

Welcome back to Underflow, a new work of serial fiction by Robert Cottrell, presented by The Browser. Underflow arrives twice-weekly in your inbox; you can opt in or out of receiving any of our newsletters (including Underflow, the weekday Browser, the Sunday Supplement, and more) by visiting your account page here.

In this episode: We overhear a conversation in St Petersburg between Bimbo, a Russian mafia boss, and Griff, a long-time friend of former KGB officer Pavel Gudichev. We begin to understand why Gudichev has founded a commodity-trading company in Estonia. Evidently, its current purpose is to launder money for Bimbo, among others. But is that enough to explain the Kremlin's keen interest? December 2012 — St Petersburg

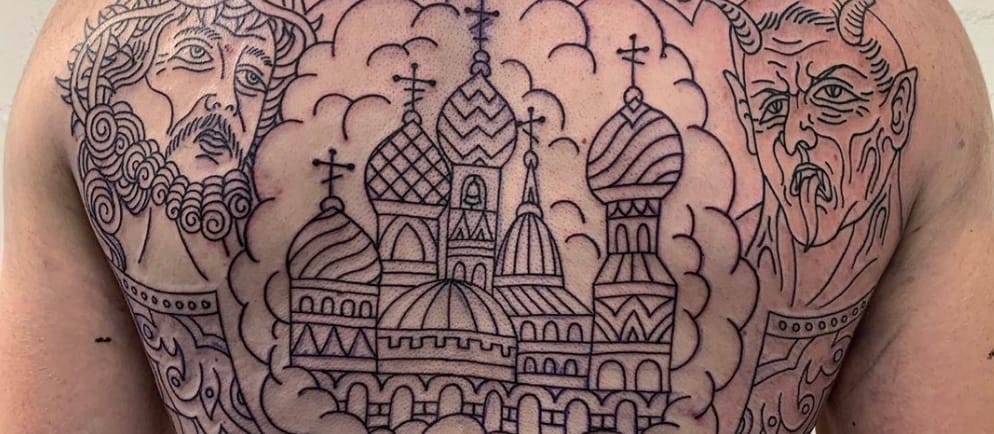

BIMBO WAS FAT MAN of sixty with dyed-black hair, tattoos down his arms, and a cigarette permanently jutting from the side of this mouth. Once he had been an Olympic wrestler. Now he was a slob and he knew it, but he was a slob in a Brioni suit. He was sitting in a restaurant in St Petersburg which had been closed ("private party") for the duration of his visit. The restaurant was called The Captain's Table. The man sitting across from him was the restaurant's owner, known to his close friends as "Griff" — from the Russian word for "vulture", which was a fair summary of Griff's appearance from the neck up. We have overheard Griff two or three times in this story, talking on the telephone with Pavel Gudichev. Gudichev had served with the KGB in Petersburg in the early 1990s, when Griff was rising through the ranks of the Tambovskaya, which was then the city's biggest organised-crime outfit. They had a lot of history in common. Griff was eighteen when a Soviet court sentenced him to ten years' imprisonment for robbery with violence. He served all ten and rather enjoyed them. While in prison he joined the Tambovskaya, acquired a ferocious horde of tattoos, killed three people with his bare hands, read Dostoevsky, played football, and learned to cook. When he came out in 1991 the Tambovskaya gave him a job as a bouncer at a nightclub on Nevsky Prospect, then put him in charge of the club bar, then promoted him to manager of the club with his own crew. In mafia terms Griff was a "made man". But he had never become a capo, an avtoritet. In this he deferred to Bimbo, his companion that afternoon, who ran the business affairs of the Kubanskaya, the largest criminal gang in Moscow and in all of Russia ("excluding", as Bimbo sometimes joked, "the Russian government"). The Kubanskaya, like all big Russian gangs, had two main "verticals". The "business" vertical, under Bimbo, acquired and ran the Kubanskaya's corporate assets, which over the years had come to include an oil company in Siberia, three large mining companies, two aluminium smelters, a chain of distilleries, a property portfolio, a supermarket chain, five casinos, and a shipping line. The other vertical, "human problems", was head by Pasha The Punisher. Nobody ever used Pasha's given name, nor even knew it, save for Bimbo and a very few others. If Bimbo offered to take over your company, and you declined his offer, then you met Pasha. If you worked for Bimbo, and you stole from him, then sooner or later you met Pasha. If you worked for Bimbo, and another gang started giving you trouble, then you told them: "We are with Pasha". If they persisted, which they rarely did, then they met Pasha. Pasha was no philistine or fool. His grandfather had been a member of the Soviet Academy Of Sciences. His father had been a member of the Writers' Union. But Pasha's formative years had been spent with the Soviet Army in Afghanistan. From there he returned with a range of appetites which were frowned upon in most walks of civilian life, and which sometimes taxed even the patience of his brothers in the Kubanskaya. Nor, for that matter, was Bimbo any slouch. He had a post-graduate degree in mathematics and had taught for three years at Moscow State University before transferring his attentions to the delights of private enterprise in the early years of Mikhail Gorbachev. Bimbo had persuaded the owner of a small bar in the Arbat to let him run a nightly poker game with friends from the university and then with any regulars who cared to buy in. He paid his percentages to the bar owner, and to the Kubanskaya, which "protected" the bar. He explained to his new Kubanskaya friends that they could probably make use of a mind like his. Within a year he was keeping the Kubanskaya's books, managing the Kubanskaya's money, and identifying the companies which the Kubanskaya would acquired for pennies on the dollar during the privatisations of the Yeltsin years. If this had been all that Bimbo had done, then he might, like Boris Berezovsky, have become a public figure, an "oligarch", in the Yeltsin years. But Bimbo had also done things from which even Berezovsky had recoiled. He had sold nuclear warheads to Chinese middlemen from the ex-Soviet stockpile. He had co-founded the cartel which had monopolised Russia's imports of cocaine since the early 1990s and which still did so. He was better off in the shadows. He drank tea, looked expectantly at Griff, and waited. Griff looked again around the empty room, leaned forward, and spoke just loudly enough to be heard against the background music: "The Estonian option is active. Nobody knows anything. The banks understand that Gudichev has a trading business and a financial business. They're dizzy with the amount of money he's been running through their books. They're using this gadget of his that makes international transfers without the bank having to lift a finger. Basically, we can send anything anywhere." — "What if they catch on?" "The very-worst-case scenario is that the banks close our accounts, after giving us enough notice to empty them. Under no circumstances will they willingly blow the whistle. The last thing they want is a reputation for confiscating their customers' money, or for shopping their customers to the police. Gudichev thinks we're fine unless something very fundamental changes. We're giving the banks terrific business, we're letting them set their own commissions, they're making huge profits out of us, and we are giving them a story that they can believe in for as long as it suits them to go on believing in it. So, no recourse, no real downside." — "And Gudichev's commission?" "Half a percentage point. He's put a lot of money into this."

Gudichev had indeed put a lot of money into "this", the Estonian project, although, to be fair, none of the money was his own. By drawing on the cashflows of Vantor, which was his oil-trading business in Switzerland, and with quite a lot of technical help from the Russian security service, the FSB, Gudichev had created what was by all appearances a thriving commodity-trading business in Tallinn. And, occasionally, Gudichev's Estonian company, Talcow Capital Partners, did indeed trade a commodity or two, if not remotely on the scale that it claimed. Now and again, when a buyer in Jersey settled via Talcow with a seller in Monaco for a train-load of copper for collection or delivery from Kazakhstan, then a train-load of copper did indeed move from Kazakhstan to Kaliningrad, or from Kaliningrad to Shanghai. But not very often. The most difficult time for Gudichev was when he wanted to show balances of a billion dollars at both Bank Livonia and Dansflur Bank in Estonia. For this he had to borrow money from the Russian Central Bank, which in turn required authorisation from the Kremlin ("The Big House", in Gudichev's and Griff's code). Since this was a project of national interest, the authorisation was granted. From Gudichev's point of view, everything was now going as well as it possibly could. But he had to accept, in simple logic, that any chain of actors and events, however robust, must have a weakest link. In this chain the weakest link was Lars Lipp, the Estonian banker whom Gudichev had hired to run Talcow Capital Partners. Lipp was irreplaceable. And, as Gudichev had been taught in his KGB training, in an operation of national importance, no asset could be irreplaceable. But this was not a KGB project. Gudichev was inclined to let Lipp run. At some point Lipp might even be brought inside the tent. Or not. The immediate aim was to make Bimbo happy, which meant laundering as many billion dollars and euros as Bimbo thought it useful to launder. Eventually Lipp might realise what he was doing. But even then, all, being well, Lipp would not know why he was doing it. To Gudichev, the important thing was to know your enemies. As a general rule your worst enemies were your former friends when things went badly. If Gudichev lost large quantities of Bimbo's money then Bimbo might (literally) have Gudichev flayed alive, and the Big House would prefer not to know the details. By comparison with Bimbo, Gudichev had nothing to fear from the European monetary authorities, or anybody else outside Russia. He would launder Bimbo's billions, and Bimbo's friends' billions, and then he would see. To be continued ...

THE BROWSER: Caroline Crampton, Editor-In-Chief; Kaamya Sharma, Editor; Jodi Ettenberg, Editor-At-Large; Dan Feyer, Crossword Editor; Uri Bram, CEO & Publisher; Sylvia Bishop, Assistant Publisher; Al Breach, Founding Director; Robert Cottrell, Founding Editor. Editorial comments and letters to the editor: editor@thebrowser.com

Technical issues and support requests: support@thebrowser.com

Or write at any time to the publisher: uri@thebrowser.com Elsewhere on The Browser, and of possible interest to Browser subscribers: Letters To The Editor, where you will find constructive comment from fellow-subscribers; The Reader, our commonplace book of clippings and quotations; Notes, our occasional blog. You can always Give The Browser, surely the finest possible gift for discerning friends and family.

|