|

The First Amendment is a major obstacle, scholars say — but it isn’t insurmountable

Here's this week's free edition of Platformer: a report on the legal challenge that TikTok has in front of it now that a bill banning it is on the precipice of becoming law. I talked to scholars about what the government is likely to say in court — and whether TikTok can beat the evidence.

Do you value the sort of work we do around here? If so, consider ~upgrading your subscription today~. We'll email you all our scoops first, and you'll be able to discuss each today's edition with us in our chatty Discord server.

On Tuesday, the Senate voted overwhelmingly to pass an aid package for Israel, Ukraine, and Taiwan that also includes a measure to force the divestment of TikTok. Observers expect final passage of the bill sometime in the next day or so; President Biden has indicated he will sign it. When that happens, Congress will have passed the first significant regulation against a tech platform since the backlash against social media began at the end of 2016. TikTok has told employees that it considers the bill a violation of its First Amendment rights, and that it intends to challenge the law’s implementation in court. Today, let’s talk about how that legal fight is likely to play out. Interviews with legal scholars suggest that the government will have a difficult time proving that its effort to ban TikTok is constitutional. But First Amendment cases are often unpredictable, they say — and it’s possible that the government’s appeals to national security could ultimately lead the Supreme Court to uphold the law. The First Amendment prohibits the government from passing laws abridging the freedom of speech. With some narrow exceptions, if US elected officials decide they don’t like the content on a given social app, the First Amendment prevents them from banning the app outright. That matters in the TikTok case because Congress members have openly criticized the content it hosts. “It’s a propaganda machine that promotes disinformation under the influence of our nation’s greatest foreign competitor,” wrote Rep. Mike Flood, R-Neb., in an op-ed last year. And they aren’t only concerned about propaganda from China. Members of Congress have also repeatedly accused TikTok — without evidence — of pushing pro-Hamas content related to the war in Israel. (TikTok has denied manipulating recommendations in this way.) The Supreme Court has previously held that Congress can’t ban foreign propaganda, including propaganda from China. In Lamont vs. Postmaster General, the court considered a law that required the postmaster general to detain “communist political propaganda” sent through the mail. The Post Office was then required to send the addressee a card asking whether they wanted the propaganda to be delivered, in what the court ultimately ruled had an unconstitutional chilling effect on speech. If Congress can’t even require people to fill out a form to receive propaganda, the logic goes, it seems even less likely that the Supreme Court would find that Congress could ban TikTok over the still unsupported claims that it is deliberately amplifying pro-China or pro-Hamas content. “It’s a fundamental principle of the First Amendment that the government can’t ban speech on the basis that they don’t like it, or that they’re convinced it’s going to convince people of ideas they don’t like,” said Evelyn Douek, an assistant professor of Law at Stanford Law School and First Amendment scholar, who pointed me to the Lamont case. For that reason, the government probably won’t rest its arguments on the idea that it has a right to ban propaganda. What about data privacy? Another core argument made by Congress in deliberations over the TikTok ban is that the Chinese government could force ByteDance to turn over user data for surveillance or other nefarious purposes. But the government will likely struggle to make a convincing argument that banning TikTok is necessary for protecting Americans in this way, scholars said. “If the Chinese government wants data on Americans, they don’t need TikTok to get it,” wrote Alan Z. Rozenshtein, an associate professor of law at the University of Minnesota, in a piece for Lawfare on Monday. “They don’t even need to steal it. The United States is a notorious outlier among developed nations for its lack of a national data-privacy law. This means that the Chinese can just buy from data brokers and other third-party aggregators much of the same information that they would get from having access to TikTok user data.” The data privacy argument may strike courts as particularly weak given the dramatic restriction on speech that will come with banning an app used by 170 million Americans. “It’s the worst imaginable means of trying to protect users’ privacy, because it’s going to shut down an entire vibrant platform or require its divestment,” said Genevieve Lakier, a law professor at the University of Chicago. And even if ByteDance were willing to divest from TikTok and preserve the platform as it exists today, forcing it to do so could also be considered an unconstitutional violation of its speech rights, she said. “If we think the owners own the platforms in part because they want to articulate certain kinds of views, this is effectively saying ‘shut up,’” she said. That leads to the argument that the government is likely to make the loudest in court: that banning TikTok is necessary to protect national security. China is an adversary of the United States and may one day seek to exploit its control over a major news and information network like TikTok, the argument goes; therefore, Congress has a compelling interest in preventing it from doing so. Of all the arguments the government could make, this one is most likely to resonate with the Supreme Court, Rozenshtein said in an interview. “The government can’t just say ‘national security’ and do whatever it wants," he said. "But courts — including the Supreme Court — just give a lot more leeway to the government in First Amendment cases about national security.” What arguments might the government make? Rozenshtein expects to see discussion of China’s active manipulation of domestic media, including sweeping censorship and propaganda efforts. The State Department last year published a comprehensive report on China’s efforts to reshape the global information ecosystem, which found that it “employs a variety of deceptive and coercive methods.” At the same time, Congress has shared no public evidence that ByteDance or TikTok have manipulated recommendation algorithms to spread pro-China propaganda or otherwise undermine national security. For the ban to stick, the government first has to prove that it isn’t about the content of the speech of TikTok. Assuming the courts accept that argument, they would likely apply what is known as “intermediate scrutiny” to the government’s case that this is a privacy and security issue. And in that case, Lakier said, the government would typically have to provide evidence of a threat large enough to justify eliminating a significant platform for speech. “First Amendment cases have been clear for a hundred years now that even when regulating speech in a content-neutral way, the government needs to have really good evidence for what it’s doing,” she said. “The thing about intermediate scrutiny is that is that we don’t take the government at its word — it has to show its work.” Another point TikTok has in its favor is Project Texas, the company’s $1.5 billion effort to move all US user data to the United States and put US-based Oracle in charge of auditing it for compliance. Courts may see that as a good-faith effort to address Congress’ data privacy and security concerns, and the government officials that negotiated Project Texas never said publicly why it was not sufficient. “I would not be surprised if TikTok goes into court waving Project Texas around — and the government is going to have to have a good answer,” Rozenshtein said. The history of First Amendment jurisprudence would suggest that Congress’ effort to ban TikTok could very likely be overturned. And yet all of the scholars I spoke with said they found this case very difficult to predict. First Amendment cases are unpredictable in general, they said, and the current Supreme Court has often shown an active disregard for precedent. “National security tends to be a context where fundamental constitutional rights unfortunately do give way, and we do see courts bow to the pressure,” Douek said. “So there absolutely is uncertainty. Even if I’m 110 percent confident that the precedents say one thing, that doesn’t make me anywhere near 100 percent confident that that’s what the court will say.” If it is upheld, Rozenshtein told me, it will likely come down to the fact that the Supreme Court is generally loath to undercut Congress on issues of foreign policy. But doing so might have an even more dramatic effect than Congress is intending here, Lakier said: creating a precedent that foreigners do not enjoy the protections of the First Amendment. “Are we really going to say that foreign speakers don’t have any rights?” she said. “These are all the questions that this tees up.”

Sponsored Simplify your startup’s finances with MercuryAs a founder of a growing startup, you’re focused on innovating to attract customers, pinpointing signs of early product-market fit, and securing the funds necessary to grow. Navigating the financial complexities of a startup on top of it all can feel mystifying and incredibly overwhelming. More than that, investing time into becoming a finance expert doesn’t always promise the best ROI. Mercury’s VP of Finance, Dan Kang, shares the seven areas of financial operations to focus on in The startup guide to simplifying financial workflows. It details how founders and early teams can master key aspects, from day-to-day operations like payroll to simple analytics for measuring business performance. Read the full article to learn the art of simplifying your financial operations from the start. *Mercury is a financial technology company not a bank. Banking services provided by Choice Financial Group and Evolve Bank & Trust®; Members FDIC. Platformer has been a Mercury customer since 2020.

Governing

Industry

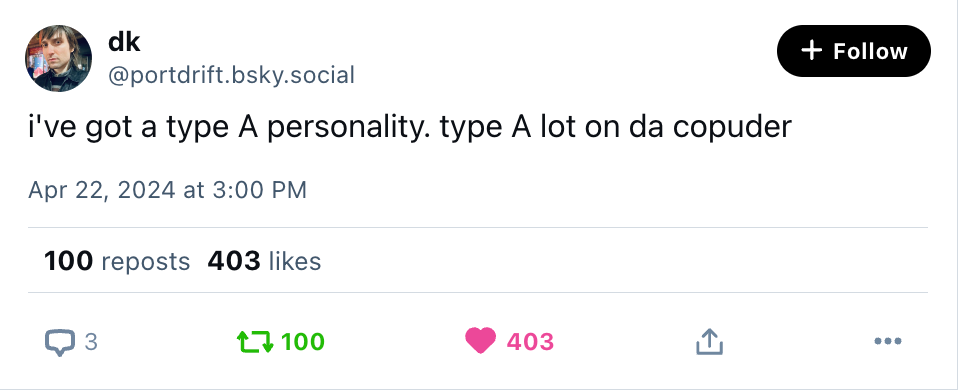

Those good postsFor more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories. (Link)

Kid: Hey look- it's the guy who's terrible at comebacks

Me: Why don't you go cook a hot dog — Viktor Winetrout (@viktorwinetrout.bsky.social) Apr 22, 2024 at 9:47 AM

Ask not for whom the bell tolls, I just got this new bell and I’m tolling it for fun don’t even stress — lukelukeluke (@lukelukeluke.bsky.social) Apr 22, 2024 at 11:08 AM

(Link)

Talk to usSend us tips, comments, questions, and TikTok legal strategies: casey@platformer.news and zoe@platformer.news.

|