[original post here]

Table Of Contents

I. Comments About Master And Slave Morality

II. Comments By People Named In The Post

III. Comments Making Specific Points About One Of The Thinkers In The Post

IV. Other Comments

naraburns writes:

I cannot possibly dedicate sufficient time to respond to this post in a thorough way. And part of that is Nietzsche's fault, because he did not spend (waste?) much time attempting to make careful points in an analytically consistent way. Even so, some things can be said about his ideas that are mostly true, and I will try to say a few of them here. (I am not a specialist in Nietzsche, but I do occasionally teach his work at the university level.)

The political status of the word "slave" in English (and especially in American English) tends to obfuscate what Nietzsche meant by master and slave morality, but the distinction is on its surface relatively simple.

"Masters" like things because they like things. Their own judgment is sufficient justification for their actions.

"Slaves" like things because other people have told them what to like:

Sometimes they are emulating the masters, but they also envy and hate the masters, so they end up doing things they themselves actually don't like, or act in resentful or spiteful ways that gain them nothing.

Sometimes they are just emulating all the other slaves ("herd" mentality)--what they "like" or "dislike" originates outside of themselves, and so they are a slave to the whims of the herd.

For example, if I buy a video game because I like it, I'm a "master." If I buy it because everyone else is buying it (or worse: because I want to show someone else who bought it that I'm just as "good" as they are because I have the same things they have--i.e. "keeping up with the Joneses"), I'm a "slave." I may engage in the slavish behavior of dragging myself through hours of gameplay I don't enjoy, because I don't want to have wasted my money and I don't want to be seen, by myself or others, as having "bad opinions."

The relationship between the "masters" and the "slaves" can be straightforwardly literal, but fundamentally, the masters don't need to rule over any slaves; what they are a master over is their own self. They don't need to "lord it over" anyone; if you have to tell people "I'm better than you because I own a Bugatti," you are their slave, your feelings are enslaved to the approval/respect/recognition of the people who are putatively "beneath" you. From Twilight of the Idols:

> “Goethe conceived a human being who would be strong, highly educated, skillful in all bodily matters, self-controlled, reverent toward himself, and who might dare to afford the whole range and wealth of being natural, being strong enough for such freedom; the man of tolerance, not from weakness but from strength, because he knows how to use to his advantage even that from which the average nature would perish; the man for whom there is no longer anything that is forbidden — unless it be weakness, whether called vice or virtue.”

The Nietzschean Overman is above others in the sense of being able to act independently of their resentment; the ubermensch could even arguably be "altruistic" in ways a slave simply cannot, because master morality allows a person to actually act "unselfishly" if that is what they deem best. Slaves are always comparing themselves to masters and/or to the herd, often in self-negating ways but never in self-sacrificing ways, because they lack the proper perspective to make a sacrifice (a slave cannot consent, because they are not free).

In short: do you tolerate others because you fear them? Then you are their slave. Do you tolerate others because you do not fear them? Then you are your own master!

More simply: do you like (or hate) Star Wars because you enjoy (or don't enjoy) it? Or do you like (or hate) it because you want to send the right signals to people whose opinion matters to you?

The idea that "slave morality is morality" might be right, but only if we agree that "morality" is just "whatever popular opinion accepts right now." That's a legitimate view that many scholars hold! But others dispute it, in various ways, on various grounds. It's not a surprise that someone called "Bentham's Bulldog" would be skeptical; Bentham, after all, declared "rights" to be "nonsense," and "natural rights" to be "nonsense on stilts." But if you think, for example, that you have individual rights that cannot be permissibly violated by a democratically elected government, then you think there is something more to morality than the weight of public opinion--and that view is not compatible with the idea that slave morality is morality.

But Kara Stanhope writes:

The Greek heroes (Nietzschean models for the supermen) of the Iliad (especially Agemmenon) seem very similar [to Andrew Tate] to me. The pretty armor, the prettiest girls to rape, the most slaves, the best tent positions on the beach, the sulking and petty vindictiveness, while compelling reading, always leaves me (a Girardian at heart) wondering how on earth they were models for anything other than memetic desire run amok.

Tate is pathetic because he exhibits all the above vices with none of the virtues of the Classical heroes — a willingness - no, eagerness - to sacrifice one’s life for a purpose greater than oneself, the aesthetics of male beauty in action and not mere preening (the body builder vs the boxer), the brief moments of gentleness.

Tate is closer to Agemmemnon. He thinks and acts like having the best booty makes you the brightest hero. Even in the bronze age, that was pathetic.

In the end, I appreciate Nara’s perspective, and I think it’s a useful dichotomy. But I find it hard to interpret in the context of Nietzsche so frequently bringing up Achilles and Cesare Borgia, both of whom went further than just liking the Star Wars movies for the right reasons.

I also don’t really get where Nietzsche thinks masterful values come from. Yes, you have to choose your own values, not the herd’s values - but where do your own values come from? He seems to write as if you’re born with a destiny written on your soul, and you become pathetic if you let the herd trick you into do something other than your soul-written destiny.

That’s a little more hostile than I can justify. I can, if I try, sort through some of my actions and preferences, and find some that seem “purer” and more “part of who I am”, and others that have red flags for looking good and satisfy other people. For example, I’ve preferred suburbia as long as I can remember and I continue to hold that belief even though everyone around me is a rabid anti-suburb YIMBY. On the other hand, even though I think I like travel, whenever I actually travel I can never quite put my finger on the part where I’m having fun. So maybe my suburb preference is really written on my soul, and my travel preference is a fake one made up to please the herd. But I’m not sure that all the writing on my soul really adds up to a destiny, exactly.

Hilarius Bookbinder writes:

Nietzsche scholar here (bona fides: an academic book and several journal articles on Nietzsche). I just want to note that Nietzsche is often misunderstood as defending master morality, or wanting it reinstated, or something like that. None of that is true. In fact, he describes the ancient nobles as so crude, unreflective, and unsymbolic as to be scarcely imaginable by moderns. After 1900 years of slave morality (Christianity, natch), our psychology is fundamentally altered. He writes in The Genealogy of Morals that “the bad conscience [guilt, a consequence of slave morality] is an illness, but as pregnancy is an illness.” We can’t go back to the old masters way of thinking, but we also need to get rid of slave morality, which he thinks is decadent (=anti-life] and fosters ressentiment. We need to give birth to something new.

One of the things Nietzsche is trying to do is undermine the idea that morality is immutable and absolute; instead moral concepts have changed and altered over time. In fact, slave morality flips master morality on its head: the old virtues of strength and dominance are no longer good, but now are seen as evil. The ancient dichotomy of good (strength, power) vs. bad (weakness, impotence) has been replaced with good (humility, poverty, chastity) vs. evil (strength, power). So when Nietzsche wants to move beyond good and evil, he is not talking about good vs. bad.

Nietzsche calls for a new kind of morality. He wants us to try different perspectives on living, to forge our own categorical imperative, to develop our own virtues. I should add that the idea of the übermensch is a weird one for Nietzsche: it is of utmost importance in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, but barely mentioned elsewhere. But the idea is of a world-affirming individual who has completely overcome the sickness of Christianity and can live in such a way that at the end of their lives they shout da capo! Do it all over again, without change or alteration. That’s what it means to embrace the eternal recurrence.

Maybe this gets to the heart of my confusion better than any other comment. Nietzsche keeps saying that the Superman is the one who can “write new values on new tablets”. But anyone can get a new tablet ($139.99 on Amazon) and write whatever they want on it. I could write “PAINT EVERYTHING IN THE WORLD GREEN”. Then I could spend my life trying to do that. I bet I would encounter lots of resistance (eg from my local HOA), and I could try to overcome that resistance. Would that be a life well-lived, because I chose the value? Or does it have to be chosen based on the destiny written in my soul, and if I get it wrong then my life isn’t well-lived anymore? Who decides these things anyway? Nietzsche? According to what set of values? Is a super-duper-man allowed to overturn those values? Can he get an even bigger tablet and write “ACTUALLY YOU SHOULD LIVE YOUR LIFE BASED ON CONFORMITY AND RESSENTIMENT?” Why not? Is it just people buying $139.99 Amazon tablets and writing the first thing they think of on them, all the way down?

NLeusel writes:

Something that's always puzzled me a bit is girl-power pop-feminism. They've internalized a lot of Randian/Nietzschean/master-morality ideas (be strong/powerful, don't apologize for who you are, make time for yourself, don't make yourself smaller to make other people feel better, etc.). And yet their ideal doesn't look very much like Dagny Taggart. Instead of building rocket trains to Mars out of magic green metal that cures cancer or whatever, it seems like the idealized girl-boss is just leading a few Zoom meetings and then going home to do yoga and meditate on how liberated she is, and possibly writing a pop anthem about the experience. So there seems to be some kind of strange disconnect (juxtaposition?) going on there.

(Maybe the vague unacknowledged Randian current in pop-feminism comes by way of Nathaniel Branden's popularization of the psychology of self-esteem? Idk.)

No, I take it back, this is my favorite comment.

If Nietzsche is really saying “ignore the strictures of society; pursue the destiny written upon your own soul”, how does that differ from Instagram “find yourself” therapy culture? Other than that Nietzsche expects your soul to say “conquer Europe” and Instagram expects it to say “ditch your boyfriend and date a yoga instructor”?

Also, why is everything that’s written on your own soul good? The Last Psychiatrist (who I usually think of as Nietzschean) had a scathing article about people who sink too much of their identity into their sexual fetishes, as if they were central personality traits to be proud of, rather than shameful vices to be indulged in secret. But aren’t fetishes, in some sense, the purest and most soul-written preferences we have? Preferences that date back from before we can remember, preferences which go so deep they can affect our very autonomic nervous responses, preferences which we stick to even when everyone else hates and shames us for them?

I think of Nietzscheans as the sort of people who would usually shout “Stop wallowing in your fetishes and instead achieve great things!” But if your natural tendency is to wallow in your fetishes, and you’re only trying to achieve great things because people are shouting at you, should a Nietzschean keep wallowing in the fetishes?

Without some external source of value, I don’t understand how you decide that one soul-written destiny (conquering Italy) is better than another (running off with the yoga instructor, or watching furry porn).

Ascend writes:

I'm very suspicious of the idea that *anyone* in the modern west is an actual example of master morality. SM has been the orthodoxy of western civilisation for a couple thousand years; the idea that anyone now can *really* be a practitioner of MM seems almost incomprehensible. I don't even know if the Nazis qualify: they had a huge persecution complex and a great amount of envy towards the Jews and their material success. They were obsessed with claims that Germany had been stabbed in the back and mistreated at Versailles--basically the exact same "not faaaair" childish whine that the likes of Nietzsche would attribute to all slave morality. And the resulting cruelty was as much self-righteous revenge as it was domination and glory.

Basically, the left and the right and every other ideology (insofar as its a meaningful "ideology" that people can rally around) is a form, ultimately, of slave morality. Even if it claims to hate SM, it will eventually just largely fall back into it. The alternative is to suggest that a way of thinking that has dominated civilisation for many centuries and has been unquestioned and unquestionable is suddenly, in our very special unique present, entirely up for debate in its fundamental form. And I don't find that plausible.

You can either agree with Nietzsche that SM is an illusion, like all morality, to be abandoned and ultimately transcended, or you can disagree and say morality exists and is good (and by morality you *will* mean what N calls slave morality). Actually following master morality is something you either accuse your enemies of doing, or you pretend to do to seem brave and edgy, but that nobody really does.

Okay, this is a potentially helpful corrective to the “furry porn” thesis above, but now I’m not sure what master morality even means anymore. There are plenty of people who follow their dreams, or who don’t act altruistically. What actions would I take if I wanted to embody the true pure master morality that nobody embodies?

Sam Kriss writes a long blog post on these topics, Nobody Understands Nietzsche (Except Me). It’s unfortunately subscriber-locked, but I hope it won’t be considered theft if I quote what I consider the thesis:

[Nietzsche] contracted dysentery and diphtheria; when those cleared up he started experiencing the headaches and nausea that would recur for the rest of his life...[He] never had any lovers. He proposed three times to Lou Andreas-Salomé, and was rejected three times, but she did sleep with his friend Paul Rée, and allowed Nietzsche to third-wheel in their travels around Switzerland.

This man spent his life in continual physical decay, rotting from the inside out. First his bowels, then his brain. Phlegm filled his lungs. He found sleep almost impossible. In the end he was sent away to an asylum; the story goes that he witnessed a horse being whipped in the street, and he threw his arms around the animal’s neck, weeping. After that, he vanished; all he produced were a few crazy letters to the crowned heads of Europe. ‘I'd much rather have been a Basel professor than God; but I didn't dare be selfish enough to forgo the creation of the world.’ But right up until the day they sent him away, this shivering bag of mucus and bones kept on insisting that right belonged only to people like himself, with a ‘superabundance of strength,’ and when he trampled over the weak and the sickly that was the only true justice there will ever be [...]

In his Introduction to Antiphilosophy Boris Groys writes that ‘when Nietzsche praises victorious life, preaches amor fati and identifies himself with the forces of nature that are bound to destroy him, he simply seeks to divert himself and others from the fact that he himself is sick, poor, weak and unhappy.’ Bertrand Russell dismisses Nietzsche’s philosophy as the ‘power-phantasies of an invalid.’ (As a man who really knew his way around the pussy, Russell is particularly scathing about Nietzsche’s sublimated terror of women. ‘Forget not thy whip—but nine women out of ten would get the whip away from him, and he knew it.’) Nietzsche’s sickness becomes a kind of gotcha, the final defence against his thought. Never mind the freezing storm uprooting everything in its path—it’s just a symptom. But I don’t think Zarathustra is simply a diversion or a distraction or a flimsy mask worn by the shambling creature of Turin. There have been a lot of feeble, lovelorn men pottering about the world in their mild overcoats. Most of them did not write like he did. You can’t ignore the weakness of the man or the strength of his writing. You have to stay with the contradiction. You have to grab them both.

The obvious answer is one philosophers have a strangely hard time comprehending, but almost every fourteen-year-old who’s picked up a book of Nietzsche’s has instantly recognised. When Nietzsche talks about master morality, he is not talking to the masters; he’s talking to the weak and the botched and to pimply Jimmy: to the slaves.

According to his myth, master morality is the natural creed of the free, strong, noble peoples of the world. Eventually, though, their victims banded together and decided that strength and nobility were evil, and the best thing to be is harmless and meek, and slave morality was born. Like all great and true myths, this one bears no actual relation to history. There never was a tribe of blond beasts practising an ethos of pure cruelty. It’s master morality that was invented by the weak and the botched—by one particular weak and botched individual, which was Friedrich Nietzsche. Its isn’t to compensate for his weakness. Nietzsche insisted he was strong, but he was always very specific about what his strength was made of. ‘I always instinctively select the proper remedy when my spiritual or bodily health is low; whereas the decadent, as such, invariably chooses those remedies which are bad for him.’ Master morality is a remedy by and for the weak.

According to the popular caricature, slave morality is about being nice and master morality is about being mean. But that’s not quite it. The overflowing life Nietzsche praises also encompasses ‘kindness and love, the most curative herbs and agents in human intercourse,’ and ‘good nature, friendliness, and courtesy of the heart.’ The real difference is that behind its meekness, slave morality is powered entirely by resentment: the secret, poisonous delight in being weak, being the saintly victim, feasting on the black slime of your own self-regard. According to some Oxford textbook that’s the first result that when you Google the words ‘nietzsche resentment,’ and which I’ll take as representative of the field, ‘Nietzsche is against resentment because it is an emotion of the weak that the strong and powerful do not and cannot feel.’ Not true! He’s very clear that the strong can feel resentment, but for them ‘resentment is a superfluous feeling, a feeling to remain master of, which is almost a proof of riches.’ It’s the other way round; Nietzsche has disdain for the weak because they have been overwhelmed by resentment…Nietzsche might have been weak, but he refused the comforts of resentment. His entire philosophy is a image of what it would look like to really live without those comforts.

Metaphysiocrat writes:

When Nietzsche gave his “genealogical” account of the master and slave morality, “master morality” was basically given a trivial form: the masters had labelled everything they liked “good” and the rest “bad.” And this is how Nietzscheans have continued to use it: master morality is everything they like and slave morality is everything they don’t - at least in the moral realm.

I think there are two separate things that tend to get referred to as master morality and three that tend to get referred to as slave morality. There’s nothing inherent about their being in these two categories other than Nietzschean rhetorical construction.

M1: Dominance

According to this ethos, it is good to be in charge, dominate others, and be on top of social hierarchies - not just convenient, but morally better, to the extent this frame thinks in moral terms at all.

This morality arises organically because socially powerful groups and individuals can demand obeisance of others, screwing with the intuitions of third parties to make them look valuable. (The legitimating role of this is a part of why they do this in the first place.)

The concept of “honor” fills out much of the pragmatic demands of maintaining a reputation that leads to a dominant bargaining position. You should be fearless, so no one can intimidate you. You should keep your promises to people you expect to interact with a lot, but not to nonpeople that don’t matter. You should revenge slights to your reputation with violence and practice reciprocity. Much of this is of course instrumentally useful for the rest of us to, while other bits are counterproductive or hard to universalize.

Legitimation in modern societies demands more subtlety than this, but some moderns like Nietzsche or Bronze Age Pervert look back to an age of warlords and pirates where this could proceed in a relatively unmediated way. Part of what’s going on here is cope - by loudly rejecting the dominant “slave morality” they get to imagine being a warlord or pirate rather than an office drone - and part of it is admiration for the honesty of an unmediated kind of domination. I don’t think it’s coincidental that there’s clearly a personality type attracted to this type of discourse, and it isn’t an actual warlord or pirate, but someone who feels very acutely dominated by more subtle social signals.

M2: Excellence

This says it’s good to be strong, smart, and capable. This isn’t always expressed in moral terms, but most of us find this to be admirable.

This is the intuition least in need of explanation, in part because I think that on a biological level, this is what a sense of admiration is for. You see someone doing something well and then want to see what in their technique to copy or try out. It feels good to be capable and is instrumentally useful for just about everything.

A lot of social conservatives are worried that this will disappear. I think there are often subcultures that deliberately crush these intuitions and that it’s generally bad to be in one, but these have always been mere subcultures (and as subcultures they’ve often performed useful roles, even if you wouldn’t want to stay there long.)1

S1: Reverse Dominance Coalitions

This is the intuition at the heart of left-wing politics, and at least according to Christopher Boehm (c.f. “Hierarchy in the Forest”) it’s a key group strategy that helped our homo ancestors diverge from alpha male dominance model beloved by Nietzscheans and actually practiced by most other great apes. In human foraging societies, people who get too powerful are gently cut down to size, and if they don’t get the message, killed. This protects group members from domination by individuals or cliques.

Even the Nietzschean master class can practice - indeed, often needs to practice - S1 internally. The Roman senators who killed Caesar were all slaveowners, as were the elite of the Southern states who feared an overweening king and later federal government, and the attachment of both to abstract concepts of liberty is well known. M1 and S1 agree, after all, that you shouldn’t let some external authority boss you around.

S2: Humility

This says: make yourself small and harmless. Have the goals of a corpse. Here is Ozy's discussion:

> Many people who struggle with excessive guilt subconsciously have goals that look like this: I don’t want to make anyone mad. I don’t want to hurt anyone. I want to take up less space. I want to need fewer things. I don’t want my body to have needs…"

This arises organically in either hierarchical societies dominated by M1 or egalitarian societies dominated by S1, or just in highly decentralized societies where you don’t know who you might accidentally piss off. M1 can foster S2 by demanding obeisance from others and punishing them for not doing so, while S1 can make people worried about sticking out and being taken (sometimes accurately, sometimes not) as a potential master. Especially in the first scenario, S2 can, like M1, derive from cope.

Although both can inspire dislike of the master class, the basic idea behind S1 is “it’s bad to be a slave,” while S2 says “it’s good to be a slave.” S2 is even more contradictory with M2, but contradiction exists in the human soul just fine. In the case of flunkies in power structures, M1 and S2 can be very compatible: deriving joy from being both a faithful servant and loyal instrument to one’s superiors, and from exercising power over everyone else. No armed body of men, I suspect, could function without an unhealthy helping of both.

Moreover: just a little bit of S2 can keep you sane, since the natural default is to think very highly of yourself. A bit of humility helps avoid pointless dick-measuring contests, reminds us we might be wrong and that pobody’s nerfect.

S3: Universal Benevolence

Mozi called this jian ai, Christians agape, Buddhists metta: a lot of beautiful words for this appear across Eurasia shortly after the introduction of writing, which I don’t think is a coincidence: writing promotes both consideration of others who aren’t immediately next to you and abstract reasoning, which naturally leads to an ethic of considering and advancing everyone’s interests impartially. “Utility” and “categorical imperative” aren’t especially beautiful phrases, and they draw attention to differences in technical specifications2, but they also appear in an era of increasing literacy, long-distance communication, and technical sophistication. There’s a long tradition of claiming the novel, as a form, is an agent of this as much or more than abstract philosophy.

Nietzscheans don’t like this because they’re partisans of M1, which exalts victory in zero-sum games. Even more offensively, S3 means that the weak have claims on the strong, that in a sense they can impose obligations on them. But there’s no contradiction between M2 and S3 - EA is a scene where both are highly present, for instance, and I think it benefits from it.

*In praise of clarity*

To lay my cards on the table, I am a partisan of M2 (excellence), S1 (reverse dominance coalitions), and S3 (universalism). I feel all of them, since they arise organically and shall ever be with us in some form or another. These aren’t the only relevant moral intuitions, just those that tend to get labelled “master” or “slave” moralities.

If you do want to use “slave morality” and “master morality,” I beg you to be clear about which of these - or which other things - you’re referring to, rather than slipping in equivocation.

I think you can always split things into more subcategories (or merge things into grander umbrella categories), but I appreciate this attempt to clarify things.

Fern writes:

I think Nietzsche's distinction in relative value between master and slave morality is that master morality is pro life, seeks to fully unravel the potential in things, while slave morality is a product of being damaged, a curse at life. Nietzsche puts emphasis on the physiological weakness of the slave minded type (seperated from literal historical slavery), and calls it the mark of the declining type. He sees the spread of slave morality then as the end of history and dissolution of man, whereas master morality keeps building a bridge towards some future.

He's not exactly setting up a universal dichotomy, where morality is master or slave, either/or and you have to swallow one pill or the other. Rather they are historical phenomena, the two principle modes that come down to us by the particular path we've taken. Master morality then is superior inasmuch as it's forward and life loving, but it's not a terminus in the possibility space of morality.

The great task that he sets up in his Superman is the revaluation of values, the transcence of historical accidents in the development of morality. Master morality happens to have more to offer in his view, but I suspect he'd grant that is open to contention when in a less polemical mood. I think he'd argue that, given there are no moral facts, altruism may well be "good" but this cannot be straightly derived out of slave morality, it must be sanitised of underlying metaphysics, which really are masks for underlying psychology. On the other hand the virtues of master morality are more readily translated by the Superman. The master perspective that spurs elaborate arguments in favour of eminent greatness is more akin to where Nietzsche sees the transcendence of morality leading.

I hate the terms “pro life” or “life affirming” for this. Vitalism isn’t literally pro life in the sense of “cause there to be more life” - it neither recommends preserving your own life (by being safe) nor preserving others’ lives (by being altruistic). More often, it’s used to recommend the opposite of those things. So in what sense is it about “being pro life”. “Well, you’re only truly living insofar as you follow our philosophy”. Very convenient redefinition you have there.

AshLael writes:

I felt like Scott was groping around trying to reinvent chivalry without quite realising that's what he was doing.

The idea of chivalry of course was that knights would seek to distinguish themselves by their virtue. The virtues they were to aspire to were laid down in the codes of the orders they would seek to be accepted into. So there was that desire and drive for greatness - the quintessential chivalrous man was a literal knight in shining armor. He was brave, and fierce, and deadly on the field of battle. But he also protected the weak, was courteous to women, kept his oaths, fought with honour and showed mercy to a vanquished enemy.

The reality of chivalry probably never lived up to those noble ideals. But what real world has ever lived up to any ideal?

A modern day chivalry might exalt rich successful capitalists - while also insisting that they don't do the bad things that rich successful capitalists are known for. To be inducted into the Order of the Sparrow you need to have a half a billion in net worth - but also you need to be honest and fair in your dealings, and be faithful to your wife, and treat women with respect, and donate a hundred million to charity, and treat your employees with decency and dignity, etc. And if you do those things your membership in the Order of the Sparrow makes you a highly admired man that everyone wants to do associate with. And if you fail to uphold them you get tossed out of the Order and that's a terrible scandal and people worry how it might look to associate with you.

I think Orders - voluntary association groups that place strict demands on their members - are a surprisingly under-explored tool. But maybe their very rarity suggests there’s some reason they won’t work.

Bentham’s Bulldog, whose surprise that anyone would endorse master morality inspired the post, wrote:

I agree that the stuff you're criticizing--corpse morality, opposing trying to do grand, powerful, transformative things because you're afraid of shaking things up, and you see morality as a series of prohibitions rather than as prescribing how to act--is quite common and bad. That wasn't really what I had in mind when I discussed slave morality, and not what most people seem to have in mind (I don't know how many people picture it a grand display of master morality to build the malaria nets but MOAR). What I was criticizing in my piece was, I think, largely orthogonal to what you defend here, though I agree the vibes are similar. I don't really have many disagreements.

Yeah, this makes sense, I just wanted to make sure different people with different definitions weren’t talking past each other, and explain what I personally saw in master morality.

Bulldog wrote a fuller reply on his own blog, Neither Master Nor Slave But Utilitarian, which I mostly agree with. But I don’t think utilitarianism (or any other philosophy) removes the need to think in these terms. In theory, you should be neither right nor left, neither capitalist nor communist, neither pro-US nor pro-China, simply choosing The Good at every opportunity without reference to puny mortal concepts. In practice you have to use some kind of heuristic and join some kind of coalition, and so all these things become important again.

(to be clear, I’m not suggesting Bulldog said the opposite; only riffing off the title)

I did appreciate this meme, though:

Walt Bismarck (whose right-wing defense of master morality I dismissed in the post as “but I like bad and cruel”) writes:

Yes, I emphatically disagree with your values and think they are bad. You don't get to simply assert that your own values are universally applicable and that anyone who substantively disagrees is "not interested in morality." That's not how philosophy works.

It would be one thing if you could meaningfully ad baculum, but rationalists and Effective Altruists are substantially weaker than tribalists and ingroup preference enjoyers, so to anyone outside your bubble this tendency just comes off as impotent sneering.

Several other people agreed his explanation of vitalism deserved more of a hearing than being dismissed as “I like badness and cruelty”.

A slightly (but only slightly) more charitable version of the exchange might be:

>> Bulldog: I don’t like master morality because it’s not altruistic and doesn’t care about suffering.

>> Bismarck: Yes, in fact I don’t care very much about altruism and suffering. Here are some other values I care about more.

I guess describing Bismarck’s answer as “I like being bad and cruel” is unfair, insofar as Bismarck didn’t endorse [violating his own moral system], and insofar as Bismarck has his own complex and consistent moral system he’s following.

But I don’t really find this objection interesting. Suppose I call Hitler bad, and Hitler counters “No, see, I have my own moral system based on the purity of the German race, and according to that system I’m doing the right thing”. This doesn’t change my “Hitler is bad” opinion at all. It’s naturally implied that I’m using the word “bad” to refer to something like “bad within my own moral system” or “bad within the moral system which I believe to be true”.

I guess maybe I committed a sin of obfuscation: “I like being bad and cruel” suggests that Bismarck himself thinks that what he’s doing is bad, whereas I meant that he’s saying “I like [being bad and cruel]”, where [being bad and cruel] is my (Scott’s) judgment of what he’s describing. Fine, I’m sorry and I’ll try not to do that in the future.

Bismarck and I had a longer conversation about this starting here, I wrote up some of my thoughts in Altruism And Vitalism As Fellow Travelers, and Bismarck responded to an earlier version of some of those thoughts here.

Jason Crawford writes:

1. » “The old pro-embiggening world was complicit in moral catastrophes - racism, colonialism, the Holocaust, the destruction of much of the natural world…”

More than just this, there was a naive belief in the pre-WW1 world that progress in science, technology, and industry would naturally go hand in hand with progress in morality and society. Condorcet believed that prosperity would “naturally dispose men to humanity, to benevolence and to justice,” and that “nature has connected, by a chain which cannot be broken, truth, happiness, and virtue.” https://books.google.com/books?id=K3RZAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA233

Historian Carl Becker wrote in the 1930s of the old belief that “the Idea or the Dialectic or Natural Law, functioning through the conscious purposes or the unconscious activities of men, could be counted on to safeguard mankind against future hazards.”

The World Wars shattered these illusions. In the next paragraph Becker writes: “Since 1918 this hope has perceptibly faded. Standing within the deep shadow of the Great War, it is difficult to recover the nineteenth-century faith either in the fact or the doctrine of progress. … At the present moment the world seems indeed out of joint, and it is difficult to believe with any conviction that a power not ourselves—the Idea or the Dialectic or Natural Law—will ever set it right. The present moment, therefore, when the fact of progress is disputed and the doctrine discredited, seems to me a proper time to raise the question: What, if anything, may be said on behalf of the human race? May we still, in whatever different fashion, believe in the progress of mankind?”

2. I'm an expert on Rand (I've read some of her books). I think even if you see her arguments/“proofs” as weak, you can at least gain something by seeing what project she was engaged in and what direction she was taking it. (A great blogger once said you should “Rule Thinkers In, Not Out.”)

Rand was not satisfied with existing moral systems and wanted to create a new one. She wanted it to (1) be grounded in reason, not faith, (2) value life, action, effort, achievement, greatness (“embiggening”), and (3) justify an *enlightened* egoism / classical liberalism—not to justify violence, domination, slavery, tyranny. (This is not necessarily a complete, definitive, or fundamental account of her project, just three relevant aspects here.) I think all three of those are very good goals. We might say that faced with the choice of master vs. slave morality, she wanted to abolish slavery altogether.

Her answer to “so why should I follow law or morality?”, in my interpretation, is roughly: Because a moral and lawful world is actually better to live in than an immoral/lawless one, and you following the rules is part of that. If you break the rules, then either you suffer negative consequences (which is bad), or you are in a world where people can break the rules with no consequences (which is worse). Now, this is not an airtight argument, but I think it is directionally correct, and it's worth more work in that direction.

Also, I don't interpret her philosophy as saying that if you're making rockets, you should only think about how the rocket makes cool explosions, and not about how it will help the world. Helping the world by creating economic value, which you then trade with others, is very Randian, at least if you also personally love your work.

Richard Hanania writes:

Scott Alexander in his article on Yglesias as Nietzsche uses "Nietzsche" in the way I do, which is a stand in for "good things are good." I tend to think the actual Nietzsche believed in things neither of us would endorse, but if that's the modern understanding of him we can go with it. See footnote 3 here on the point about what gets called "eugenics" these days. If you disagree with that footnote, it's a good litmus test proving that you subscribe to slave morality, and not the more defensible kind of slave morality, but like the ugly stuff we should wipe off the face of the earth.

I thank Hanania for some earlier discussion which probably helped inspire this article in some vague way.

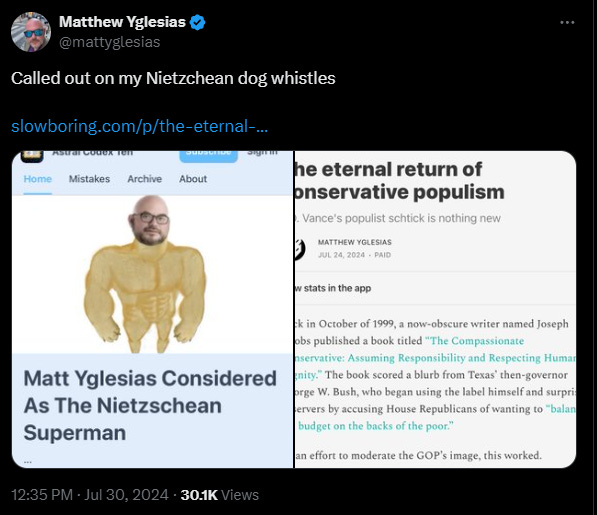

And Matt Yglesias on Twitter:

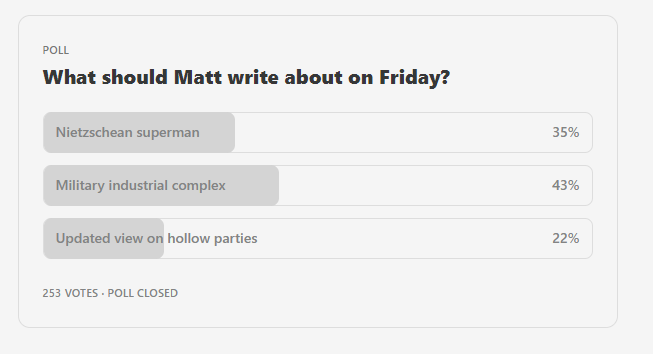

Matt has a deal where every week, his subscribers can choose a question for him to answer at length. This week’s poll was deeply disappointing:

…really? The military-industrial complex? Are Matt’s subscribers really able to will the eternal recurrence of that decision? Pathetic.

Yossarian writes:

>>[Ayn Rand] really really wants to think that you can objectively convince people to support a peaceful, glorious, positive-sum society, without any hint of the psychologically-toxic slave morality that typified the USSR she grew up in.

Rand is not so different from USSR's morality. When I first read Atlas Shrugged, I felt a strong sense of deja vu that I couldn't quite place. Only after reading the whole thing I realized I was reading a very typical Soviet book of Rand's time. Yeah, really so. There was a whole sub-genre in Soviet science fiction that was quite like that. Basically, if you take any of these old Soviet books, and change the heroes' speeches from "Communism brings progress" to "I want to be selfish and bring progress", but leave the entire rest the same - you'd get Atlas Shrugged.

MaxEd writes:

I also have to object to "toxic slave morality of USSR". I know it's still popular to dunk on Soviet Russia, since it has failed in the end, but it seems like most people get their knowledge of Soviet culture from Cold War sources tinted with a heavy dose of propaganda. Or Ayn Rand herself. Soviet society always celebrated unique individuals - actors, scientists, sportsmen, no less than its Western counterpart. It just denied hyper-rewards for such individuals: top Soviet actors, for example, still lived in apartments (if a bit nicer than your ordinary worker), not in mansions behind high walls and security. Frankly, I can't say their acting was worse off for all that.

I guess you can say that while there was no "official" slave morality in USSR, the rules were set up in such way to actually encourage it, e.g. by writing a letter to NKVD/KGB about your more talented peer to cut them down. While I agree that this is true to some degree, I think all societies in all times had something like that - from reporting someone to Inquisition, to reporting to him to Un-American Activities, to reporting to HR for harassment, an individual talented at "office games" can always make life of someone more talented at actual work miserable. I guess it was easier in USSR for most of its existence, compared to contemporary Western countries, and it was detrimental to nation, but to call all of USSR "slave culture" because of that is an overreach.

Jukka Välimaa writes:

When thinking about Rand and egoism and altruism, it's good to keep in mind that by "altruism" she means something different than most people. She's talking about altruism in the same sense as the originator of the word, Auguste Comte: as otherism, living for the sake of others, self-sacrifice.

So, for a Randian egoist: Helping others because you value them, out of a sense of generosity and great-heartedness? Fantastic! Helping others out of a sense of duty, stunting your own life and happiness? Nope!

As far as efficient altruism goes, most people espousing it seem to think in utilitarian, rather than purely altruistic terms. Under utilitarianism, helping others in a way that also helps you is *obviously* better than helping others in a way that makes you miserable, other things being equal.

I like this reading of Rand, it feels like the sort of thing the steelmanned/perfected version of Rand in my head would say, and it’s definitely what I’d use if I were her PR person - but it’s not the impression I get from her books. I could be convinced otherwise if you could find her saying this in so many words.

William H Stoddard writes:

I've come to think that The Fountainhead is the key to Rand's view of Nietzsche. Not just because she originally planned to use a quotation from him as its epigraph, but because of its major conflict between Howard Roark and Gail Wynand. Wynand really is something of a Nietzschean overman: born in the slums, he educated himself, became a successful newspaper publisher, is hugely rich, and besides that, is a lethally skilled fighter and superb in bed. And he's driven to seek power. But Roark is not a Nietzschean overman, though he's mocked as one a couple of times: He cares about his work, not about power. I see this as the debate between the Nietzschean Rand and the Aristotelian Rand who wrote Atlas Shrugged. (If you read Aristotle's account of the megalopsychos or "great-souled man," it's almost a perfect fit to what Rand says about Roark.)

But Ultimaniacy writes in response to William:

> “And he's driven to seek power. But Roark is not a Nietzschean overman, though he's mocked as one a couple of times: He cares about his work, not about power.”

No, the point is exactly the opposite! Roark is a model overman, embodying will to power -- not power in the vulgar sense of political influence, but in the Nietzschean sense of mastery over his own will. Wynand represents a *failed* overman, who had a mind capable of transvaluing all values, but instead chose to debase himself and become a slave to public opinion.

I’ve never read The Fountainhead and don’t have a position here.

Tanthiram writes:

This is a fantastic piece, and I have nothing smart to say about the actual substance, but I hope it slightly eases one of the conflicts in the middle if I say that Andrew Tate was a mediocre kickboxer at best. Kickboxing "world" titles vary wildly in quality due to the number of promotions, and none of Tate's were good (for one, he beat a 43-year-old who'd won 1 of his previous 7 fights). He also just looks like he kinda sucked. Crisis averted!

(Maybe I'm proving the whole "cutting down the big arrogant men" thing of slave morality, but then I think this also supports that it can be a good thing when they're frauds)

Patrick F writes:

I'm a bit embarrassed to know so much about Tate, but here we are.

> scammy courses

I do literally make money with (partly) what I learned in that program (and no I'm not scamming anyone either)

> Some of his courses apparently recommended beating up women

False

> he sent one of the victims a text message saying “I love raping you”

Consensual BDSM relationship confirmed by both parties

> Finally he was indicted on one billion counts of sexual assault

Does anyone find it a little weird to be accused of rape by a government, and not, say, a person who was raped?

> human trafficking

I assume that's "paid for her plane ticket so she could consensually join my webcam business" in which case yeah, guilty

> if he becomes a normal civilized person who says please and thank you and is really respectful to everyone?

He does those things. Watch any interview and see if he doesn't. His blind rage is comedic and reserved for a faceless audience, not real present people. But you're conflating niceness with "cares what lesser people think", and indeed Tate doesn't do that. There are other reasons to be nice

Your gut was right; Tate is exactly what slave morality was designed to defend against

The 4chan losers are just a herd of their own, alike in temperament to the globalist prog herd. Multiple "opposing" herds just use each other to enforce ideological purity on their own side

I admit that I know nothing about Tate except that I’ve seen some bad tweets by him and heard he was involved in sex crimes. I looked at his Wikipedia page which seemed to agree. If you’ve already read the Wikipedia page, you shouldn’t treat me as an independent source confirming that he was involved in awful sex crimes.

Wesley Fenza writes

My nomination for the Ubermesch is TracingWoodgrains, the notable gay furry formerly of the Blocked & Reported podcast and currently notorious on Twitter for his provocative essays. When I read Scott’s essay, he was the first person I thought of. One of his highest values is excellence. It informs everything he does. He is constantly advocating for the metaphorical poppies to get taller, and rages against our education system that encourages equality by holding back the more talented kids. He makes no apologies for it and doesn’t begrudge anyone pride in their achievements. But he also maintains an ethic of civic duty, and feels an affinity with his former Mormon community over their mutual desire to improve the world, create thriving communities, and engage in mutual aid. A true Nietschean master concerns himself only with his own excellence, but Trace is constantly encouraging and supporting others to become more excellent. This is on clear display in his essay on why he is voting for Kamala Harris despite the fact that she represents a political machine that is an anathema to his values.

While Yglesias manages to balance a desire for greatness with humility and egalitarianism, Trace balances the bronze age values of excellence, honesty, and individual merit with the liberal values of pragmatism, fairness, and broadly distributed prosperity.

To be clear, I think all of this is nonsense, and I don’t think any of this matters, but if you’re the type of person who feels they need a moral compass, you could do much worse than Trace.

The blogpost’s thumbnail (which you can see at the link above) continues on our surprisingly-consistent theme of Nietzschean superman + furry porn.

Tohron writes:

Christian morality is compared to slave morality here, but I don't think they quite sync up.

A core component of my own Catholic morality is that every person is uniquely valuable as an individual existence. This value is independent of anything they accomplish, and thus, secure from the opinions of other people. Since it is secure, there is no need to tear down other people in order to protect it.

The Gospels do feature some stories that could be seen as pro-slave morality, where Pharisees and Sadducees hold themselves as superior because they're better at following the social rules of the time. But Jesus' criticism of them isn't that trying to find rules on how to be good and follow them better is bad - it's that they've become so fixated on the literal rules that they've lost sight of the actual purpose of the rules: loving and caring for the people around them.

Meanwhile, the Gospels also feature many parables where people are unhappy with other people receiving good things that they felt weren't deserved. The message of these parables is that being bitter about other people's success can only hurt oneself - it is much healthier to celebrate other people's joy.

So, how do you go from there to nuns rapping the knuckles of anyone who wants to do something big, or fixations on guilt and unworthiness? Well, history is complicated, but I suspect anyone who's unhappy with where their life went might have a hard time opening up about it, and it's always easier to convince yourself that current things are fine and that anyone aspiring to more is in the wrong.

But to me, Christianity offers the idea that no matter what, you are valuable and you are loved. And it also has the message that each person has a unique calling which should be sought out, encouraged, and celebrated (not for what it achieves, but for each step a person takes closer to what they were meant to be). In sort, my understanding of Christianity is hardly incompatible with seeking out great things.

I agree that “Christianity” can mean any tendency that anyone held at any time during 2000 years of Western civilization, and shouldn’t be taken as a monolith.

Susan Greenberg writes:

I’d like to pick up on the passing comment, near the start of this post, that Nietzsche thought slave morality originated with the Jews. If that is so, it can only reflect the extent to which his Christian upbringing and cultural environment distorted his (and his followers’) understanding. Jewish morality is very much based on actions, not beliefs, which would put it in the “enbiggedness” camp. And the emphasis on enlittleling (humility, sacrifice etc) is very much a Christian thing, used through the ages to demonstrate their superiority to the Jews that they had replaced — it’s the core of antisemitic supercessionism.

I’m skeptical of this. My favorite counterexample is the Torah, which says that Moses was the most humble man in the world (Numbers 12:3), plus the ensuing scholarly debate on how Moses himself could write this in the Torah with a straight face. My favorite answer claim that God forced Moses to write that he was the most humble man in the world, but Moses fought back by making some of the alephs in the Torah really small as a sort of steganographic claim that he was embarrassed by having to praise himself. See also this essay, “In the Jewish tradition, humility is among the greatest of the virtues, as its opposite, pride, is among the worst of the vices.”

In general I’m skeptical of most attempts to draw a bright line between Jewish and Christian philosophies (“Jews think like this, Christians think like that”). Christianity grew out of Judaism, and most post-1400s Jewish scholarship was written in Christian societies, so both religions had ample chance to influence each other. “Everybody knows” that Christianity judges you by belief and Judaism judges you by your actions, but the Talmud says “The following have no part in the World to Come: One who says that the resurrection of the dead is not biblical, or that the Torah is not from Heaven, or the Epicurean.”

Martin Susrik writes:

The tall poppy syndrome may be a more ancient and fundamental thing than it seems to be at the first sight.

Acemoglu & Robinson write about societies systemically destroy anything that sticks out. Tiv (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiv_people) being their example of choice. Living in the state of perfect equality is paid for by always living at the edge of famine. On the other hand, living in the state of equality on a continent where slavery is rampart has a value of its own. If nobody is allowed to become rich and powerful, they won't enslave you.

Here's a paragraph how the elimination of successful was done:

> “The Zulus were lined up and Nobela [the witch doctor] and here associates began "smelling out" the witches who had brought on the evil omens. They picked on prosperous people. One had grown rich through frugality. Another had put cattle manure on his lands as fertilizer, producing a bountiful harvest much greater than his neighbors'. Yet another was a fine stock breeder who had picked the best bulls and taken great care of his stock and as a result had seen a prodigious expansion of his herds.”

That having been said, I agree anthropologists have proven pretty conclusively that the Jews didn’t invent slave morality and it’s as old as humanity itself. I included a tweet about the Mbendjele people in the original, but I could have emphasized this part more.

I’ve heard stories of missionaries and philanthropists in Third World countries ending up dejected by how impossible it is to get a lot of primitive tribes to join the 21st century and do Capitalism. The suggest the tribespeople start some business to provide needed goods to their village, but the tribespeople complain that if they made money, they’d be socially required to give it to their inlaws/clan/spend it all in a huge feast for the village, so what’s the point?

10240 writes:

I don't see Matt Yglesias's points as summarized by Scott as much of a compromise. It's still *almost* pure Second Form Slave Morality stuff, even if radical SJWs and commies are purer.

What I'd regard as a compromise would include points like these (matching the original numbering):

2-3. Some people are obviously better than others in terms of talents and skills, including genetically, there's no need to deny or minimize that. However, having better talents and skills is a totally different thing from having more moral worth. Everyone has equal moral worth, everyone's wellbeing deserves to be taken into consideration with equal weight. (Or if not, that's determined by the (im)morality of their actions, not their talents.)

4. If someone happens to end up unusually skilled or powerful, we should expect them to use their skills for the benefit of society. In exchange, they get full respect and praise (nothing wrong with that if we're going for First Form Slave Morality). We tolerate them ending up with somewhat money than others because it helps with the efficient allocation of labor, but we redistribute income from them to the poorer to the extent it doesn't hurt prosperity too much.

6. Technological progress, economic prosperity, and cultural sophistication are good because they make people better off. Benefitting anyone is, all else equal, a good thing, whether it's a poor or a rich person, albeit benefitting poor people by a given amount is more valuable because they need it more (this is the part we grant to slave morality). Equality is not an end in itself, but for a given economic performance, it's better if it's distributed more equally. Art is good since it entertains people.

I'd say this is still mostly slave morality. I'd describe it as First Form Slave Morality, or as a compromise between Second Form Slave Morality and Master Morality, or as utilitarianism.

Do we have to compromise as much as Matt does? If we granted less to slave morality, would we grant too little for it to be a compromise? I don't see it. Not only does he lie far on the slave side of the slave-master morality divide, his "compromise" is still left of center even in modern Western society, which is already mostly slave moralist. One could take up the mantle of classical liberalism without the shibboleths about benefitting from privilege, or including underrepresented groups as the main saving grace art can have.

I think the way I wrote it is one end of the Overton Window, the way 10240 writes it is the other, and to me the window seems small enough that I don’t see much difference between our two formulations - but I appreciate the criticism.

Walliserops writes:

I am a native of 4chan. Let me give you an insider's perspective.

Every social media website has a guiding motto, agreed by everyone who joins but never spoken out loud. For example, Reddit's is "everybody ought to think like I do". What began as a way to vote on posts grew into a hyper-conformist dystopia, and now any opinion that goes against the grain is not only dogpiled on but quite possibly banned for the terrible perils that such wrong information may pose. Forget controversial political opinions - saying "you can keep a betta in a 2.6g" in the aquariums subreddit will mark you as a public enemy.

(fun fact: Because Reddit has multiple sub-communities with competing interests, this creates an interesting behavior where threads about topic X on "neutral ground" are actively contested by pro-X and anti-X factions. For example, the top post of any World News thread about Turkey is a 50/50 on "Turks are anti-Western extremists with multiple genocides under their belt and a strongman in the mold of Putin at the helm, we should kick them out of NATO and shun them forever" and "Turks are a great civilization that have fallen on hard times, we should sympathize with their plight and hope that they recover from the disaster that is Erdoğan". Whichever faction didn't win is handed 200 million negative votes).

(extra fun fact: one of Erdoğan's nicknames is Şerdoğan, i.e. the Hawk of Evil, so it's really on the Turkish people for voting Griffith into power).

Anyway, Twitter's motto is "I am so much better than that fellow over there". What began as a way to facilitate one-to-one exchanges grew into a clapback dystopia, and now every public figure is hounded by digital hyenas looking to one-up their posts and earn their fifteen minutes of please-check-out-my-GoFundMe. If you're not clapping back at individuals, you're clapping back at Platonic ideals of things, hence all these posts to the tune of "Dear straight white men: Please stop hunting down street cats and slurping their intestines directly out of their bellies, and for the love of everything good stop calling it 'paleo-ramen'".

4chan's guiding ideal is "who you are doesn't matter, only what you say and do". You can go right now and ask the animals board about how to house a leopard gecko, the toku/mecha board about which Kamen Rider series to watch first, the dollkeeping thread about the best brands for accessories, or the sci-fi thread about books similar to Baru Cormorant. They will help you to the best of their ability. But the moment you display any personality traits beyond "I want to do X and would like to know how", they will turn on you. The easiest way to become hated on any board is to be recognizable - anyone who uses a tripcode or a character avatar to post is treated as a digital leper.

(Why does 4chan have such a beef with furries and transgender people? Because they're all about identity and self-expression, and 4chan responds to self-expression the way Elphaba responds to a shower. Other parts of the LGBT+ community* are treated with more respect because "I want to fuck dudes as a dude and would like to know how" is the kind of thing 4chan can parse. Similarly, people on other social media networks now expect you to preface all your sentences with "As a level 12 Lawful Neutral Oath of Vengeance Paladin of Tyr who likes horses and would describe her periods as 'fairly mild'...", and 4chan expects people on other networks to fall in a ditch and die).

So why the hateful posts? Well, the other point of 4chan is that what you say in thread X has no bearing on thread Y. Everyone expects you to behave in their threads, but you don't carry any of the good or the bad to others, so there's a smaller societal cost to being an utter turd once in a while. On one hand, it creates some truly vile posts by attention seekers. On the other, it's a good mechanism for self-improvement. If you say in other social media that black people should be allowed to ritually kill and eat one white child on national TV every year to atone for slavery, you'll be known forever as the child eater guy and never let into polite society again. On 4chan you're allowed to conclude that child cannibalism is not a good solution for the legacy of slavery, and come back with better ideas that will be judged on their own merit instead of "here's the latest hot take from the child eater guy".

But (and I can't believe I'm saying this) there is still a twisted moral fiber to 4chan - the kind of bully that Scott describes will probably met with just a handful of replies, half of which will be "t. retard". Besides, as anyone who spent any time on 4chan would tell you, the age at which a woman shrivels into a desiccated corpse and joins the ranks of the sokushinbutsu is 25, not 40.

I like this way of thinking about “who you are doesn’t matter, only what you do”, but I find the connection to 4chan kind of tenuous.

HumbleRando writes:

Scott, what I find so contemptible about your morality is that it assumes that the weak are GOOD, and DESERVE to be helped. Whereas the truth is that quite a lot of them - like the third-world refugees that Europe is importing by the millions - are horrifically evil people who would rape your family to death if they could get money and clout for it. Their weakness does not mean that we should sympathize with these people, because the second they gain power they will use it against their benefactors. Your philosophy of life continually fails to account for that.

Please note that this isn't a defense of Nietschean morality, which I find equally contemptible. Nietschean morality is simply your own, except with the polarity reversed. Instead of the weak being fetishized as paragons of goodness, they fetishize the strong.

What I am proposing (and what makes my morality superior to both sides) is that good or evil should be judged completely independently of weakness or strength, using objective measurable criteria to determine who is deserving of help and who isn't. The reason rationalists with their "effective altruism" will never be a popular movement is because they do not DESERVE to be popular when they have no logical moral criteria to evaluate whom their altruism should prioritize. When your "effective altruism" saves the lives of 300 sub-saharan africans who then go on to murder gay people indiscriminately because their religion tells them to, or immigrate to Europe and rape and kill twelve year olds, YOU are personally responsible for the deaths they caused. Before you criticize OTHER people's morality, maybe you should consider subscribing to a moral philosophy that actually considers downstream effects, instead of treating the lives of evil people as being equally valuable to the lives of good people. Or do you not BELIEVE in the concept of good and evil?

I calculated it out based on statistics in this article and some wild assumptions, and I think since 2000 there have been a total of about 7,500 sub-Saharan African convicted rapists in Europe. If we assume the total cases are 20x convictions, that’s 150,000 actual sub-Saharan African rapists (for a sanity check, this is about 5% of all male sub-Saharan Africans in Europe.)

There are about 1.2 billion total Africans, which suggests that if you save a random sub-Saharan African, there’s order of 1/8,000 chance they’ll go on to commit rape in Europe. I don’t think killing 8,000 people is worth it to prevent one rape. If you do think this, I think you should favor (for example) nuking random European cities, since I’m sure that you kill more than one rapist per 8,000 people.

(as for killing gay people, probably the gay people they kill are also sub-Saharan Africans, and I’m not sure you’re really coming off super credible in your desire to save the lives of sub-Saharan Africans here).

This reminds me of the section in Part IV of the post about how slave morality “ignores benefits and treats harms as infinity”. Sure, saving 8,000 Africans will save 8,000 lives - but it will also cause one extra European rape, so I’m “personally responsible” and “not considering downstream effects”.

I think that saving 8,000 lives but causing one rape is better than killing 8,000 people and preventing one rape. This is the only deal on offer. If you want to take the opposite side, I think you have some personal responsibility of your own to consider.

Jude writes:

I got the feeling Scott was suggesting that the underachieving masses are embracing slave morality while the successful tycoons of industry today are still "masters." I think this is completely backwards in an age of global capitalism. Spend any time at all with underprivileged boys in the US or boys from macho cultures in unstable developing countries and you will see that they are the true inheritors of Achilles' and "master" morality. Rap music in the US is the ultimate Nietzschean product: a world where what is good is just what gets one ahead: big cars, big houses, hot women, respect. These are the kids who love Andrew Tate, but his ideas are hobbling them in their efforts to get ahead.

Then go work at a reasonably functional corporation or government agency and see who gets ahead and gets promoted. It's certainly people who take initiative, build new skills, and try things. But it's also overwhelmingly *people with good social skills and balanced pro-social tendencies.* Soft and social skills are frequently cited as the biggest reason why otherwise talented people don't move up. What makes companies money is the ability to run a big delicate cooperative network - and to do that, they need a lot of people who are good at cooperating, who understand and live out pro-social norms even if they aren't doing it for altruistic reasons. Modern HR departments are the most vicious defenders of egalitarian morality - not because they have a "slave mentality," but exactly because they don't. They are part of ruthlessly profit-oriented organizations whose success depends on coordinating the skills and labor of tens of thousands of human beings - often in different countries - all with different experiences and thoughts related to their sex, ethnicity, education, age, etc. Ironically, the spread of global capitalism and demand for increasing labor has made this necessary. You can't afford to allow discrimination or social blind spots in your execs because your competitors will find undervalued sources of labor and beat you with them.

This is a good point. I agree that rap is a weird master morality relic.

Patrick D Farley writes:

The phenomenon of mixing master virtues with slave virtues, as seen in early progressivism, early socialism, etc., is very interesting. I don't know if Nietzsche spoke to such a situation.

But a fundamental question for that kind of society is "Do the master virtues exist genuinely, or just to lend the slave virtues more meaning?" Because, the herd does love their sacrificial heroes. We love that Harry Potter is a powerful wizard _who sacrifices his life for the herd_. We love that Jesus is infinitely powerful _so he can save us_. The greater the power, the more meaningful the sacrifice - that is one way to valuate power. The other way is to value power for its own sake. In which case you'd use the altruistic virtues as means to more power: build a network of people who owe you a favor; leave a good impression on everybody so they vote for you, etc.

The socialist propaganda, we can safely say, is in the former category. Be a winner and then surrender it all for the cause. You want the taxidermy'd bust on your mantle to be the most ferocious, virile specimen of whatever you hunted - it's a greater testament to your ultimate "rightness" as the hunter. This perverse valuation of power characterizes exactly how masculinity is dealt with in Christian circles today, for example.

I think the real litmus test is: How does the society treat people who gain power and _choose not to_ offer a sacrifice to the herd? A society that's honestly a mixed-bag of virtues would say "we don't love that you've chosen not to help anybody, but you're not harming anybody, so whatever. At least you inspire us or make our country look cool, and if we're organized properly then you prob had to help a lot of people on the way up". A society that only values power as a means to sacrifice would be outraged and try to take the sacrifice by force.

More good points.

Related: John writes:

Nietzsche has good psychological insight, but I think that he offers a distorted perspective for analyzing social morality. What you see as "hybrid" moral systems from a Nietzschean POV (Puritans, early Soviets, post civil war progressives, Yglesias ... ) are pretty typical in their merger of embiggening and ensmalling virtues. My guess is that only sick, disordered societies are dominated by either slave or master moralities (obviously, most societies have have had both b/c it's hard to be a slave w/o a master or vice versa).

The idea that slave virtues reinforce each other and drive out master virtues may have some truth for individuals, but there is a natural limit to how far slave morality can expand in society b/c no pure slave morality society would survive. A hunting tribe can survive if they exile that one annoying dude who makes everyone else look bad by working too hard, but they'll starve to death if no one wants to excel at hunting of if they decide that it is morally wrong to exploit other animals by killing them for their meat.

Zinjanthropus writes:

I think the ultimate reason that the Nietzschean idea of the superman fails is that being superman is ultimately unsatisfactory, even to Superman himself.

At nearly 3,000 years old, the Iliad is very much in vogue, with two recent notable translations by women (Emily Wilson and Caroline Alexander) and a book of criticism aimed at a broad audience, Robin Lane Fox's Homer and His Iliad. I think part of the reason the Iliad still hits home is that its central figure, Achilles, fascinates. He's not just stronger and faster and better-looking than everyone else, he's more thoughtful and eloquent too. People point to his appearance in the underworld in the Odyssey, where he says he'd rather be a hired hand on a farm and alive than rule over all the dead. But his rejection of the heroic ethos is found in the Iliad too. His superhuman strength and beauty can’t save him from being dishonored by Agamemnon. It can’t keep his beloved Patroclus alive. All it’s good for, ultimately, is slaughtering Trojans. Which Achilles does magnificently, when he finally returns to battle; but in a sort of frenzy of despair. To a Trojan begging for mercy, he says: Patroclus is dead; I’ll be dead soon; you die too. He calls himself a useless burden on the earth. At the end when he forgoes violence and returns Hector’s body to his aged father Priam, saying sadly as he does so that he is doing nothing to help his own aged father; instead he sits in Troy, afflicting Priam and his children. And he agrees to hold the Greek army back for two weeks so that the Trojans can give Hector a proper burial.

It is impossible for me to imagine Achilles fighting the Trojans again after his interview with Priam, though the story of the Trojan war requires it; for that reason, I think, Homer ends the Iliad with Hector’s burial, with the truce still in effect.

Some critics have argued that there was an earlier poem, an Achillead, in which Achilles’ killing of Hector and mutilation of his body in revenge for Patroclus was presented as a fully satisfactory conclusion, both to Achilles and to the poem’s audience. The later bits of Achilles’ despair and his mercy, in this account, were bolted on later. I have no idea if the Achillead ever existed, but I do know that if it did, it would be forgotten today.

The Iliad teaches us that revenge is never fully satisfactory; dominating and lording over others is not enough. It's interesting to contrast the chivalric epics with Homer. Achilles comes to see his own supreme excellence in combat as pointless and futile. Lancelot and Galahad and Gawain don’t feel that way about their own prowess. But why not? Because they use their excellence to protect the weak and defenseless, delivering the land from ancient evils, finding the Holy Grail. If Achilles could be transported to the world of the chivalric epics, he would be much happier and more fulfilled than he was in his own world.

I appreciate this perspective on the Iliad.

Alastair Roberts writes:

A key factor I don't think @slatestarcodex sufficiently addresses — even if he touches on it at points — is the way strong collective identities have been the way of squaring high celebration of power and excellence with affirmation of low achievers. When there are well-defined, bounded, and honoured groups, within which all group members have common, secure, and meaningful belonging, a group can encourage high achievement in its members, while also allowing all members, even the lowliest, to share in the glory. The all-important requirement for the high agency group members is that they work for the benefit and glory of the group, not merely their own.

Sports are like this: people expect sportsmen to give their all for the team and they share in the glory when their side wins. Where there is a sense of being a strong and united team, where the highest achievers are striving to achieve glory for the shared identity, it really can produce a much higher tolerance for the inequalities that a society that celebrates excellence and high agency produces. Where such shared identities fail, the lowliest will tend to fall back into ressentiment, envy, hatred, felt inferiority, and will stigmatize and seek to cut down winners.

Those who see shared identities slipping away from them can feel an existential challenge along these lines. This is one reason why many people, despite being poor or disadvantaged, can love things such as nationalism, monarchy, or empire. It connects them to something glorious. However, where group membership is not highly valued and protected, exceptional persons can become a threat. A strong collective identity, then, need not be the flattening 'collectivism' many imagine.

This also where Richard Hanania and some vitalists would part ways with, for instance, nationalists, as Hanania et al lack a strong collective identity to share the spoils of glory. For Hanania and many vitalists, weak, sick, less intelligent, poor, and low-achieving people are mere excess human biomass. If they were to imagine an ideal nation, it would probably be extremely selective in membership, excluding, and dismissing the value of most people's lives. This is, for instance, an inner tension in white nationalism: it tends to appeal most to lowly people who feel they lack respected group membership, while also typically being wedded to a sort of vision of master morality. However, they don't have excellence or high agency. The sort of 'ensmallening' society Scott describes, which eschews and penalizes the pursuit and celebration of greatness can push greatness out of public and common life and into the realm of private enterprise, accentuating people's sense of the indignity of inequalities.

FurtherOrAlternatively writes:

As I have written before, I see part of the appeal of EA as a heroic quest for young people in a world lacking in other outlets for excellence. E.g. here:

“One reason that the improvement of material circumstances is so morally tempting today is that the improvement of people’s moral or cultural circumstances seems so difficult. If we lived in an age in which we reasonably expected our poets to produce epics for the ages, or our painters to produce masterpieces that will require the protection of glass cases in the Louvres of the future, then, I am sure, we would be far less ready to find it plausible that the most good that could be done by a bright and cultured young person educated at one of our ancient universities would be to pursue a working life devoted to the philistine manipulation of money in order to give generously to charities that distribute malaria nets or arrange complicated webs of kidney donations. For all the good that such a life might accomplish, there is surely something limited, something mean or monochrome, about the idea of setting out to live it. To relieve the most hunger among the most people would be a worthwhile achievement for a pig, but surely not for Socrates? “

I’m not sold on art/epics/masterpieces as a grounding for morality or the good life.