Introducing Book Gossip, a newsletter about what we’re reading and what we actually think about it. I’m your host, Emily Gould, a person who has been gossiping about books for I don’t even want to say how long, lest it make me sound very, very old. But here are my credentials: I’ve had every role in book publishing you can have except agent, which means editor, author, and publisher. I know how the book sausage is made. And yet, I still love reading books! And what I haven’t had, up until now, is a way to share all the little tidbits that come my way — the random scraps of info, the short recommendations, the reviews of reviews, and the unvarnished opinions from colleagues and randos. Book Gossip is a newsletter for people who like books — or who at least like talking about them. |

| Since you read our former books newsletter, Read Like the Wind, we think you’ll love Book Gossip, and you’ll receive it every month unless you opt out here. In each edition, you’ll find unusual or just plain weird coverage of the big new releases you’ve already heard too much about. We’ll also recommend unexpected books that match the vibe of the season or the mood or the moment and devote attention to genre books that, frankly, more people should be reading. We’ll point you to the best book coverage we’re doing here at the magazine and everywhere else. We’ll also poll you, the reader, about questions you actually care about, in the hopes that the newsletter can become a conversation that leads us all to some exciting new reads — or at least some new party conversation topics. |

| For this Book Gossip preview, I talked with my colleague Isabel Cristo about the one weird thing from Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo that we both found annoyingly distracting. I also rounded up some of the most interesting responses from Reddit and 4chan to Tony Tulathimutte’s “first great incel novel,” Rejection. If you like what you see, hang tight. You’ll get Book Gossip every month starting at the end of October. |

| —Emily Gould, features writer, New York |

|  |  | | |

|  | | Photo: Retailer |

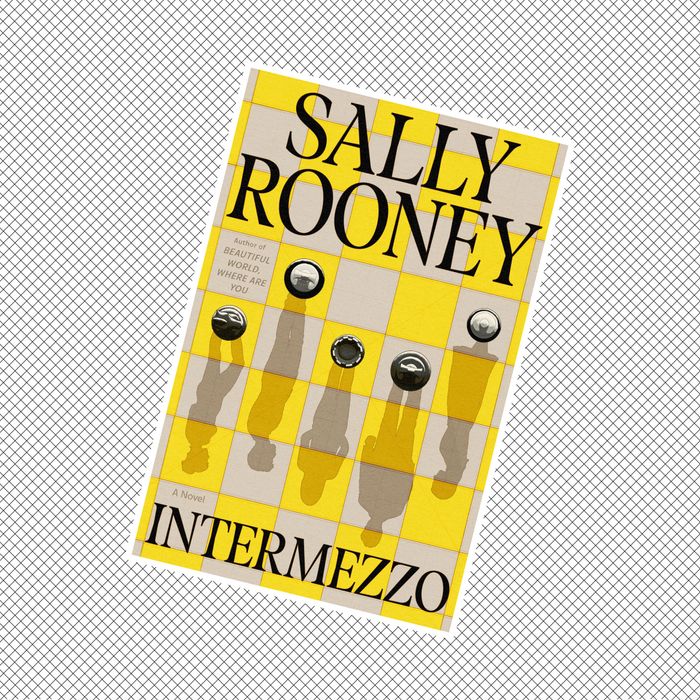

| There are a lot of reasons why Sally Rooney’s new novel Intermezzo wasn’t my favorite of her books. I wasn’t a fan of the first section, full of sentence fragments and literary allusions, and I had a hard time relating to the two male main characters. But there was one thing in particular I couldn’t stop thinking about: 32-year-old barrister Peter and his former girlfriend Sylvia, who are still in love with each other, but broke up years ago because Sylvia was in a “road traffic accident” that left her incapable of having penetrative sex. I couldn’t stop wondering about the mechanics of why, exactly, this would prevent Sylvia and Peter from having sex, and my mind went to all kinds of weird places. Strangely, Rooney never provides more details about either the accident or its physical aftermath. |

| There were only a few reviews I could find that mentioned this aspect of the book. “The end of her sexual life is cast, in some of the novel’s most troubling passages, as tantamount to death,” Alexandra Harris writes in one of them, for The Guardian. “We find little counter to the notion that Sylvia is a broken sex provider who cannot offer him fulfillment.” This detail also got under the skin of Isabel Cristo, who works as a fact-checker here at the magazine — so she did what fact-checkers do. She did some research. I asked her about her findings and her opinions. |

| Did this feel as weird to you as it did to me? And can you come up with an explanation for how a car accident might render someone incapable of sexual intercourse? |

| I called an OB/GYN who I know and I described the symptoms and asked, “Is this plausible?” And he, I think as any good medical professional would, was sort of like, “Everything is within the realm of possibility,” but the idea that this was a medical condition that was brought on by a physical trauma definitely threw him for a loop. |

| I found this detail to be so conspicuous for a couple of reasons. The first is that this book is so long, maybe too long. So Rooney certainly had plenty of opportunities to give us some more details about what had happened to Sylvia. I kept on thinking, after that initial scene where Sylvia explains to Peter what happened to her, that we would return to the inciting incident, to this car accident that happened years before the start of the book, and that we would get some clarity around what exactly happened. I associate that kind of ambiguity with short fiction or flash fiction, where the author really has to move the plot along at a clip in order to keep things going. And when we never got that moment of clarity, it felt really notable. |

| The other reason that it felt really notable is because Rooney’s never shied away from specificity when it comes to (a) the mechanics of sex or (b) the gory details of women’s chronic pain. In the past, that’s been such a touchstone for her. I think of Francis’s endometriosis in Conversations With Friends. That physical pain is something that moves the plot. At every dyad and in every configuration of every relationship it becomes this point of, “Will she reveal to Bobbi that she has this endo and will that become a point of connection for them because it is sort of this vulnerable source of intimacy that they can sort of share this secret? Will it doom her relationship with Nick because we know that he wants to have children and maybe she’s infertile? Will it bring her closer to Melissa who we know doesn’t want to have children, and maybe Francis finds herself in the same boat?” It’s a very specific and a very legible pain that you can see ricochet out into ways that make sense in the plot. |

| This just made no sense. It spurred a lot of questions that felt kind of almost inappropriate to ask oneself because you have to assume that theoretically this could happen, Sylvia is a proxy for a real woman to whom this could happen to, and you never want to be in the position of questioning a woman’s medical situation, especially when it comes to her reproductive system. But I found myself with so, so many more questions. |

| This accident is also what sets the rest of the book into motion. Sylvia breaks up with Peter because she can’t have sex, and so years later they’re still in this very weird, very close platonic relationship but are clearly still in love with each other. And meanwhile, Peter is sleeping with this 23-year-old, Naomi. Did you find the way it affected their relationship to be plausible? |

| The short answer is no. I was so confounded that this accident took place years ago, and presumably they were so close this entire time, both before but also after the accident, and that he was only just now, years later, asking her any questions about what had happened to her. To me that threw the nature of their relationship into question and the intimacy that they could possibly have had. |

| I also think it’s funny that Rooney is heralded as the voice of a millennial generation because her sensibilities are sometimes so mannered and Victorian. It’s almost like it would be impolite for the characters to know more about these kinds of mechanics, but at the same time, they’re spitting in each other’s mouths, they’re fucking every which way, they’re having all sorts of transgressive sexual experiences, but this particular conversation around the details of her pain are beyond the pale for some reason. |

| I did think that maybe Rooney was doing something, because the book is written from the perspective of two men for the most part, that maybe the lack of curiosity or the confusion or the ambiguity was meant to say something about the way that women’s pain is experienced vis-à-vis the men whom they’re sleeping with. I don’t know, does that seem convincing to you at all? |

| I think that’s a really generous interpretation … I’m sorry, I just can’t get there. Peter and Sylvia have been so close for this uninterrupted stretch of time, and he has never bothered to be like, “So what exactly would happen that would be bad if I stuck my dick in you?” |

| Not to mention that in the year 2024, it’s also sort of depressing to imagine that the absence of penetrative sex would spell the end of someone’s entire sexual life. I feel like that’s well-trodden ground for us, right? |

| No, I mean, if you read those columns that Esther Perel writes in the Cut, she’s saying exactly the opposite of that over and over again every single time. It’s like, “We have to get away from the idea that P-in-V intercourse is what equals sex.” |

| It was depressing to imagine that it was a foregone conclusion that if you can’t have penetrative sex, you cease to be a sexual being or someone worthy of sexual attention. And it was also depressing to imagine that the book was not interested in questioning that because then it made Sylvia’s character feel sort of slotted into the Madonna position of the Madonna-whore binary, Naomi obviously being a whore in this case. And I think it was sort of depressing as a reader to imagine that Rooney was playing on that trope when I know she’s smarter and more enlightened than that. Maybe that’s an ungenerous read, but it was sort of doubly distressing in that way. |

| Exactly how distracting was this detail to you on a scale of 1 to 10? Did it keep you from taking other parts of the book seriously? |

| I think I became distracted by my own fixation on it and sort of started asking myself questions like, “Why do I care so much if this fictional character is experiencing a real or fictional pain inflicted on her by a real or fictional medical condition?” It definitely felt like a mystery that needed to be resolved, and I felt kind of duped as if we didn’t find out who the killer was in the end. |

| Yeah, I think it was just a fuck up rather than something deliberate. And that’s my judgment, I have judged. |

| The characters in Tony Tulathimutte’s new novel-in-stories, Rejection, is, without exception, terminally online. In “The Feminist,” which first appeared in n+1, a man whose strenuously woke behavior masks deep-seated contempt for the women who won’t sleep with him eventually finds solace in an online forum called NS/OM, for “narrow shoulders/open minds.” There, he becomes a moderator, seeking out a community that reaffirms his belief that “narrow-shouldered feminist men are in fact the most oppressed subaltern group.” Another character is a gay online-porn addict with tastes so specific (and, to him, shameful) he can’t be intimate with anyone in the real world. |

| Though Tulathimutte hits the same emotional notes over and over again — isolation, desperation, self-hatred — the characters he created all feel very different, and very real. But I wondered how the book would be received among the very people it attempted to describe, people so engrossed in the worlds of their screens that they have found themselves posting on 4chan and sub-Reddits like r/incelexit. |

| The message boards were most interested in the book’s first story, about that narrow-shouldered chronic poster who can’t get laid and can’t understand why. “I sympathized with the character and nothing he wrote shows that the character warrants the sort of ridicule that he envisions,” an anonymous poster wrote. He was then chastised by another: “It’s the tale of a clueless simp. if u think it’s dunkin on u, then u sir are reddit i am sorry to say.” The story also struck a chord with members of r/intelexit, a community dedicated to “people who got drawn into the Incel community but want support and help with a way out.” Some of the people in this sub-Reddit seem to be seated closer to the exit than others, but all of them had strong reactions to the story. Witness this exchange between redditors yocrappacrappa and [deleted]: “This is one of cases where I can see what the author is trying to get at, but sympathise too much with main character that I can’t quite grasp the deeper meaning. I mean - him not quite getting why he is incel besides doing all the ‘correct’ things - strikes too deep for me. In reality though, what does make him unattractive? It’s not just his simping behaviour, is it? Is it that some men just have a aura of unlikability or unfuckability around them? How does one get rid of that?” You won’t learn the answer to this question by reading Rejection, nor will you learn it in this Reddit thread. In response, [deleted] writes: “It kinda is his simping behavior, or rather that there’s nothing but the simping behavior to him. I think game is an important thing for guys to learn, as well as creative outlets. Of course there’s always physical attraction and self care, but women are usually passive so even if you do attract their attention how would you know without game?” |

| The thread got a bit more disturbing from there. There’s an extended metaphor from Throwawayaft1 that compares women to unattended sandwiches. “People seem to often believe that being kind and respectful and whatever consists of asking every person in sight whether it’s their sandwich before taking it. But it doesn’t. It consists of taking the sandwich and if someone yells ‘hey that’s mine,’ apologizing and putting it back down.” |

| And yet, miraculously, one user named Melthengylf seemed to actually understand the point of “The Feminist,” and even feminism. “Part of the reason why his performative feminism fails is because the set of values that he’s trying to follow is at the core, wrong. Not the fact that he should treat women as people, that is right. What is wrong is that feminism is about a set of morals or actions. Feminism is not a rulebook but seeing women as people. But if you believe feminism IS a rulebook, then performative wokeness is really too easy.” |

| | |