Notes From The Progress Studies Conference

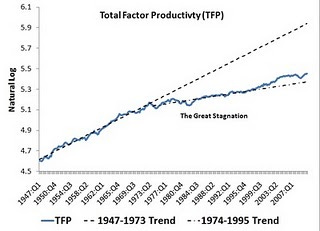

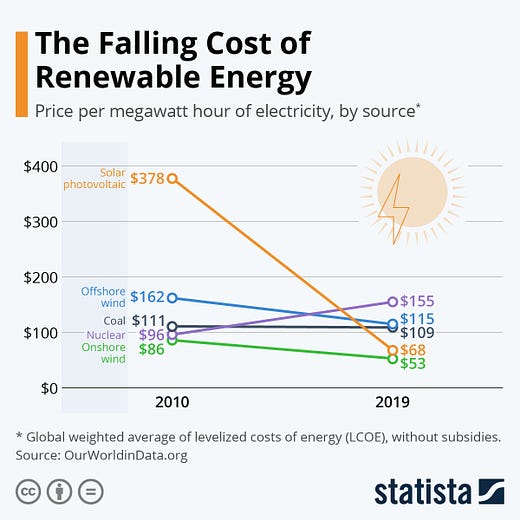

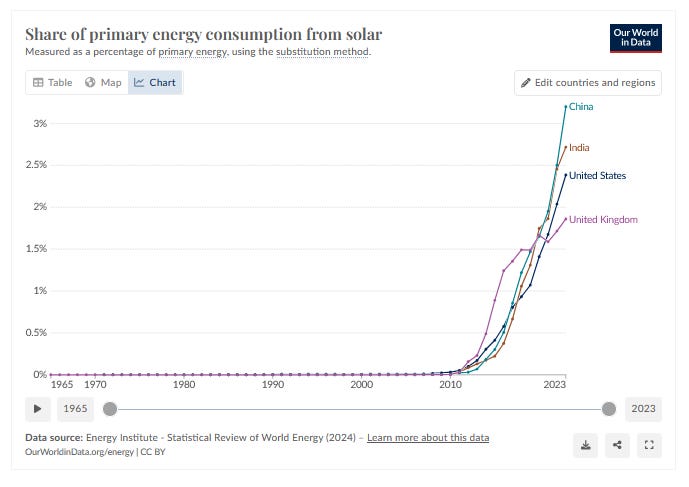

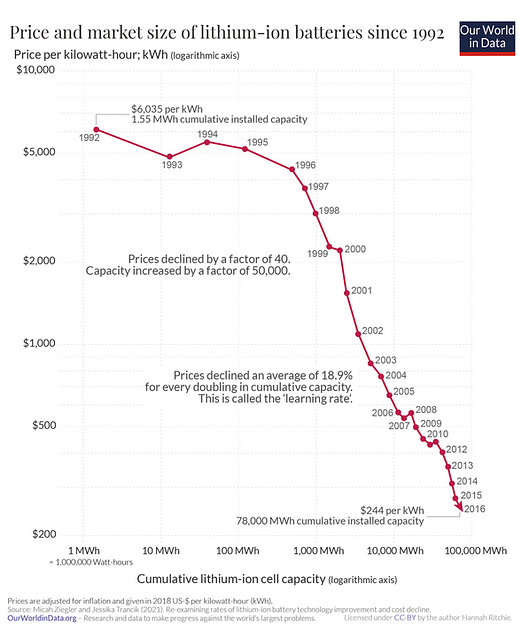

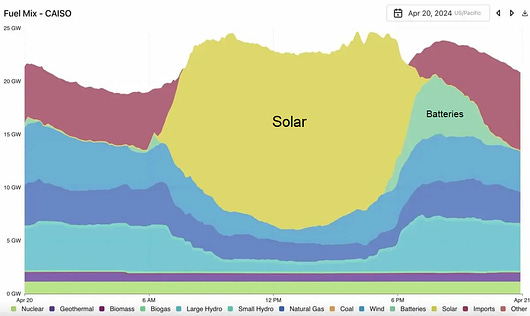

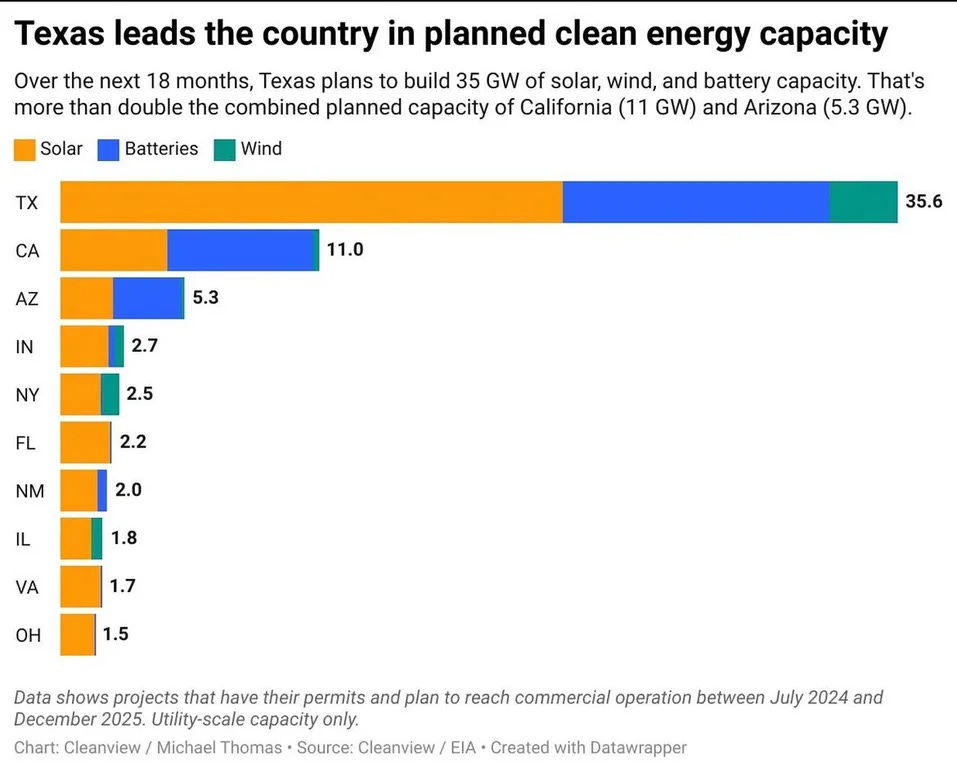

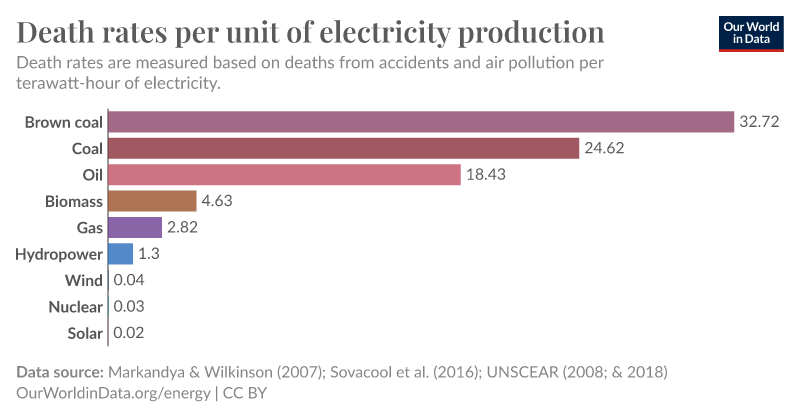

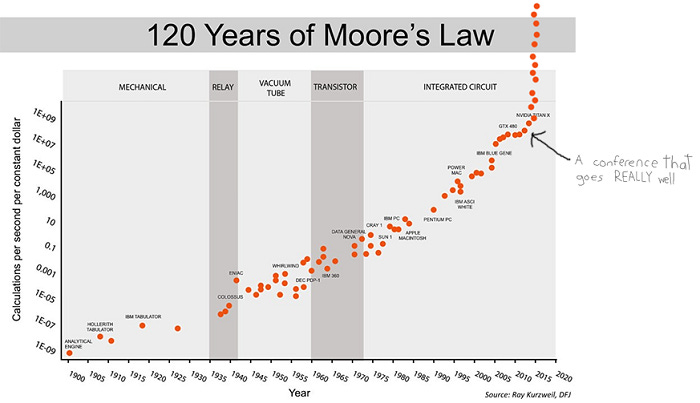

Tyler Cowen is an economics professor and blogger at Marginal Revolution. Patrick Collison is the billionaire founder of the online payments company Stripe. In 2019, they wrote an article calling for a discipline of Progress Studies, which would figure out what progress was and how to increase it. Later that year, tech entrepreneur Jason Crawford stepped up to spearhead the effort. The immediate reaction was mostly negative. There were the usual gripes that “progress” was problematic because it could imply that some cultures/times/places/ideas were better than others. But there were also more specific objections: weren’t historians already studying progress? Wasn’t business academia already studying innovation? Are you really allowed to just invent a new field every time you think of something it would be cool to study? It seems like you are. Five years later, Progress Studies has grown enough to hold its first conference. I got to attend, and it was great. The objections failed because Progress Studies is the same type of field as Gender Studies: the Studying serves as the nucleus of a network of scientists, activists, entrepreneurs and journalists working to produce radical change. The Basic Progress Studies Narrative You can find long versions of this at Is Science Slowing Down? and 1960: The Year The Singularity Was Cancelled, but here’s the short version. Progress is good. As Steven Pinker has shown, most things are getting better over time. We are richer, healthier, safer, and better-educated than our ancestors. Although redistribution and social changes can make things better or worse around the edges, most of our current fortunate position comes from simple economic growth. Progress (as measured by things like total factor productivity) was fast for much of the early 20th century, then slowed around 1970. Nobody knows why; theories include shifting social attitudes, over-regulation, or simply exhausting the potential in a few big inventions like electricity and mass production. This slowing was one of the greatest historical tragedies: if progress had continued at pre-1970 rates, we would be twice as rich today. We call the ensuing period the Great Stagnation. There was plenty of innovation in computers (“the world of bits”), but real physical goods (“the world of atoms”) stayed disappointingly similar. Our great-grandparents grew up in a world of horse-drawn carriages and lived to see the moon landing. We grew up in a world of cars and jumbo jets, and live in it still. But Tyler Cowen has declared the Great Stagnation provisionally maybe starting to be over. This is a bold pronouncement; official statistics are as dull as ever, and Progress is a field where going off vibes leads you astray. Still, advances in AI, solar, space, and biotech seemed impressive enough that he thought it represented a phase change. And this was the sort of conference you would expect in a world where the Great Stagnation was ending, with topics like: EnergyEveryone agreed that we should have 100x as much energy per person (or 100x lower energy cost), that we should simultaneously lower emissions to zero, and that we could do it in a few decades. The only disagreement was how to get there, with clashes between advocates of solar and nuclear. This year, the pro-solar faction seemed to have the upper hand because of trends like this: Between 2010 and 2019, the nuclear/solar cost comparison fell from $96 / $378 to $155 vs. $68 (yes, nuclear got more expensive). As a result: …solar’s share has dectupled in the past decade and shows no sign of slowing down. (wind has similarly impressive results, but was less-discussed. I think this is partly because solar has a slightly better exponential growth rate and because of how exponents work this means it will soon blow wind out of the water. But also, it’s easier for regulators to thwart wind, whereas most people can just put a solar panel on their roof.) Why is solar improving so quickly? Humanity is very good at mass manufacturing things in factories. Once you convert a problem to “let’s manufacture billions of identical copies of this small object in a factory”, our natural talent at doing this kicks in, factories compete with each other on cost, and you get a Moore’s Law like growth curve. Sometime around the late 90s / early 00s, factories started manufacturing solar panels en masse, and it was off to the races. Solar used to be limited by timing: however efficient it may be while the sun shines, it doesn’t help at night. Over the past few years, this limitation has disappeared: batteries are getting cheaper almost as quickly as solar itself. The remaining limitation is high-density use cases; for example, a passenger jet needs to get a lot of power from a source light enough to fit on the plane. So far batteries can’t do that. The solarists are undaunted: you can use solar power to “mine” carbon from the air and convert it into fossil fuels, then use the fossil fuels on the plane. Since you took the carbon out of the air in the first place, it’s still carbon neutral! If these trends continue, solar power could reach $10/megawatt-hour in the next few years, and maybe even $1/megawatt hour a few years after that. This would make it 10-100x cheaper than coal, and end almost all of our energy-related problems. The United States could produce all its power by covering 2% of its land with solar panels - for comparison, we use 20% of our land for agriculture, so this would look like Nevada specializing in farming electricity somewhat less intensely than Iowa specializes in farming corn. Countries without Nevadas of their own could, with only slight annoyance, do the job with rooftop solar alone; one speaker calculated that even Singapore could cover 100% of its power needs if it put a panel on every roof. And developing countries could benefit at least as much as the First World; unlike other power sources, which require a competent government to run the power plant and manage the grid, ordinary families and small businesses can get their own solar panel + battery and have 24/7 power regardless of how corrupt the government is. Despite this being a conference about the future, the pro-nuclear faction seemed comparatively stuck in the past. In the 1960s, nuclear was supposed to bring the amazing post-scarcity Jetsons’ future. It could have brought the amazing post-scarcity Jetsons’ future. But then regulators/environmentalists/the mob destroyed its potential and condemned us to fifty more years of fossil fuels. If society hadn’t kneecapped nuclear, we could have stopped millions of unnecessary coal-pollution-related deaths, avoided the whole global warming crisis, maybe even stayed on the high-progress track that would have made everyone twice as rich today. It was hard to avoid the feeling that the pro-nuclear faction wanted to re-enact the last battle, this time with a victory for the forces of Good. The pro-nuclear side insisted they also had practical arguments. Look at the top graph again. Between 2010 and 2019, nuclear cost per megawatt-hour increased from $96 to $155. In fact, nuclear has been increasing ever since the 60s, when it cost about $20 (in current dollars). This is proof of concept that nuclear can be much cheaper than it is now. If we did everything right - got really good regulations, innovated hard, switched to the most promising type of nuclear reactor - we could not just get the cost back down to $20, but go even lower - as low as $1 per MW/h within a decade or two. That’s much cheaper than solar, which is currently $68 per MW/h. (this would probably look like small modular reactors mass-produced in factories, to take advantage of the same factory-scaling trend that helped solar. Surprisingly, the best regulatory climate for this appears to be the UK, although it’s still very bad and there’s a long way to go.) The pro-solar faction countered that sure, solar is something like $68/megawatt-hour now. But by the time this extremely difficult project of changing regulations, innovating, and creating an entirely new industry is finished, then solar will probably be down to $1 - 10 / MW/h too. And solar has so many other advantages - easier to install, more practical for poor countries, harder for regulators to thwart, less likely to end with major cities being converted to radioactive ash. The nuclear faction is cheating by comparing real solar now to ideal nuclear in twenty years. Compare like-to-like, and solar is obviously better. The nuclear faction said that they’re not sure solar and batteries will continue scaling as rapidly as it does now. Therefore the case for ideal nuclear in twenty years (which we’re pretty sure is physically possible) beats the case for ideal solar in twenty years (which is just extending a line on a graph until it gets to a point marked REALLY GOOD). I thought solar won: I’ve spent my whole life as an extending-lines-on-graphs fan, and it would be hypocritical to stop now. (here’s a recent Substack post arguing against solar, but I think it makes the same mistake as a lot of posts arguing against AI - looking at where things are now, instead of where the trend line is obviously pointing) Nobody wanted to defend fusion. Fusion promises cheap clean limitless power if only we can solve difficult technological hurdles. But we already know how to produce cheap clean limitless power. The only delay is regulatory, and fusion doesn’t solve this. Won’t people be more willing to tolerate it because it’s meltdown-free? No; there are already designs for meltdown-free nuclear reactors, and we don’t use them. Also, fusion is not radiation-free, and the radiation alone would be enough excuse to regulate it to death. Is it theoretically possible that - since there aren’t existing fusion-related regulations - we’d have a fresh chance to fight the same battle and maybe win this time? Maybe, but everyone there thought that solar or small modular nuclear reactors would be an easier sell. (the only pro-fusion sentiment I saw at the conference was a series of graphs comparing “fission” and “fusion” and showing strong performance advantages for If we had cheap clean limitless power, what would we use it for? Someone asked this question in a presentation, and the cheap clean limitless power advocates didn’t have a canned answer ready to go. They eventually proposed things like improved public transit, supersonic flight, carbon capture, AI compute, geoengineering to prevent hurricanes, and city-wide air filters (really). I don’t hold the lack of a canned answer against them; I assume that when Faraday first invented electricity, he couldn’t have predicted air conditioners, dryers, or data centers. If you build it, they will come. PoliticsOver-regulation was the enemy at many presentations, but this wasn’t a libertarian conference. Everyone agreed that safety, quality, the environment, etc, were important and should be regulated for. They just thought existing regulations were colossally stupid, so much so that they made everything worse including safety, the environment, etc. With enough political will, it would be easy to draft regulations that improved innovation, price, safety, the environment, and everything else. For example, consider supersonic flight. Supersonic aircraft create “sonic booms”, minor explosions that rattle windows and disturb people underneath their path. Annoyed with these booms, Congress banned supersonic flight over land in 1973. Now we’ve invented better aircraft whose booms are barely noticeable, or not noticeable at all. But because Congress banned supersonic flight - rather than sonic booms themselves - we’re stuck with normal boring 6-hour coast-to-coast flights. If aircraft progress had continued at the same rate it was going before the supersonic ban, we’d be up to 2,500 mph now (coast-to-coast in ~2 hours). Can Congress change the regulation so it bans booms and not speed? Yes, but Congress is busy, and doing it through the FAA and other agencies would take 10-15 years of environmental impact reports. Or consider solar power. The average large solar project is delayed 5-10 years by bureaucracy. Part of the problem is NEPA, the infamous environmental protection law saying that anyone can sue any project for any reason if they object on environmental grounds. If a fossil fuel company worries about a competition from solar, they can sue upcoming solar plants on the grounds that some ants might get crushed beneath the solar panels; even in the best-case where the solar company fights and wins, they’ve suffered years of delay and lost millions of dollars. Meanwhile, fossil fuel companies have it easier; they’ve had good lobbyists for decades, and accrued a nice collection of formal and informal NEPA exemptions. Even if a solar project survives court challenges, it has to get connected to the grid. This poses its own layer of bureaucracy and potential pitfalls. The most memorable statistic from this part of the presentation: over the past few years, Texas has approved more solar power than every other state combined, and more wind power than every other state combined, and more renewable-friendly batteries than every other state combined. This isn’t because Texas is especially environmentalist. It’s partly because Texas has its own grid with less bureaucracy, and partly a general libertarian attitude that lets renewable businesses expect a fair deal from the government.

Nuclear is in an even worse situation, as you can tell from the recent $96 → $155 price rise mentioned above. This is partly because - as Matt Yglesias writes - nuclear plants are held to an “As Low As Reasonably Achievable” safety standard. Suppose an company invents a nuclear plant which is twice as cheap and twice as safe as existing models. They might like to try selling it for a bit below the cost of existing models, then pocket the profits. But the regulator will say that because it’s cheap, they have more money to spend on safety, and demand safety improvements until it costs just as much as existing models (even though the new model was already twice as safe). This declares it impossible by fiat to ever make nuclear any cheaper, which means we keep using coal forever, even though coal is much more dangerous. The solution would be to enshrine into law some specific safety standard for nuclear - maybe 1000x safer than coal power. Then inventors can start there and make things cheaper, instead of having every efficiency gain get eaten up by more safety regulation. Then more people would switch from coal to nuclear, and we would be even safer and have cheaper electricity and have lower emissions. It’s popular to blame environmentalists and government regulators for this, and they do deserve part of the blame, but the speakers at the conference urged us to also blame existing nuclear companies, who lobby the government to add more and more burdensome safety regulations so they can charge more and keep out competitors. Again, this isn’t a war between economy-boosters and sympathetic activists who want some other good. It’s just dumb laws and regulatory capture hurting everybody. AIEither some sixth sense drove me to the AI-related conversations like a moth to flame, or else everyone at this supposedly-generic progress-related conference was talking about AI. You might expect Progress Studies conference-goers to be natural accelerationists, but the mood was more subdued. Most of the people I talked to (again, maybe there was an unintentional bias) were worried about safety, understood intelligence explosion dynamics, and didn’t really know where this whole thing was going. Most continued to awkwardly support AI anyway, out of some generic loyalty to Progress. I got to attend a session on SB 1047, the recently-vetoed California AI regulation bill. The most interesting thing I learned was that California’s position as home to all big American AI companies was irrelevant - the bill could have equally well been in New York or Texas. Any state can try to regulate any industry, and the industry has to comply or leave the state; it’s almost never worth the economic loss to abandon big states, so legislation in any big state has nationwide effects. Everyone agrees this is awkward, but the Supreme Court recently confirmed that it was true in a ruling on Prop 12, California’s law demanding better conditions for factory-farmed pigs. California doesn’t have a lot of factory-farmed pigs, so this law primarily demanded that other states give their pigs better conditions if they wanted to sell pork in California (which they all do). The Supreme Court said this was fine, and presumably would make the same decision if New York or Texas tried to regulate AI. The federal government tends to think of these situations as an invitation to step in (though it hasn’t with Prop 12), and if too many states make too many confusing regulations then Congress will probably pass a law to sort things out. But for now, it’s a free-for-all. (this means the claims that “AI companies are going to leave California!” or “Elon Musk is only supporting this because his AI company isn’t in California!” were even more deceptive than I thought - leaving California would make no difference!) The other interesting claim that came up in this session was that the California legislature will pass virtually any bill, because they’re busy and hate disappointing people. Then they let Governor Newsom decide whether to veto, and never override his veto. The lobbyists and California experts in the room disagreed vehemently about this, with some defending the legislature’s honor. The only point of general agreement was respect for Scott Wiener, even among people whose careers centered around thwarting him. YIMBYI didn’t get a chance to go to the YIMBY related sessions, but they were out in force and feeling pretty good about themselves. YIMBYs have been having success after success in California. They describe themselves as passing “twelve bills in five years to legalize 2.2 million+ homes” - plus some executive orders by Governor Newsom. Now Kamala Harris seems to be on board, with YIMBYs declaring her one of their own. It’s hard to think of other movements that have come so far so quickly. I asked some of the YIMBY leaders there what they were doing - did they have blackmail material on Governor Newsom? They said politicians had finally realized that housing prices were in crisis, started groping around for solutions, and they’d been there at the right time and worked really hard to get the message out. Self-Driving CarsAfter a few disappointing years, these are finally coming into their own. The expert I talked to said Tesla had made some bad decisions and was no longer in the top tier, but that companies like Waymo and [I can’t remember which other ones he named] were near the finish line. They’re already safer than humans in most situations and operating successfully in several cities. The remaining challenges to scaling up are mostly regulatory, not technical. Here the regulatory challenges are less about specific laws than general nervousness on the corporations’ part to be seen expanding too quickly. They want to build a strong record in friendly cities before venturing further. The most interesting new claim I heard was that self-driving cars could help the environment by encouraging carpools. The UberShare carpool program hasn’t taken off, but that’s mostly because people are reluctant to share a car with a stranger. Self-driving cars have more design flexibility, and you might be able to turn them into a series of private pods. You could sit in your own private pod while your robotaxi made a two-block detour to pick up a second passenger.

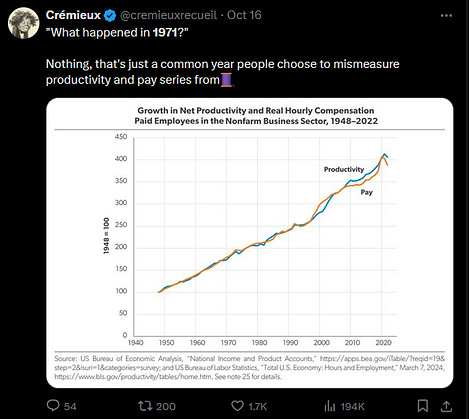

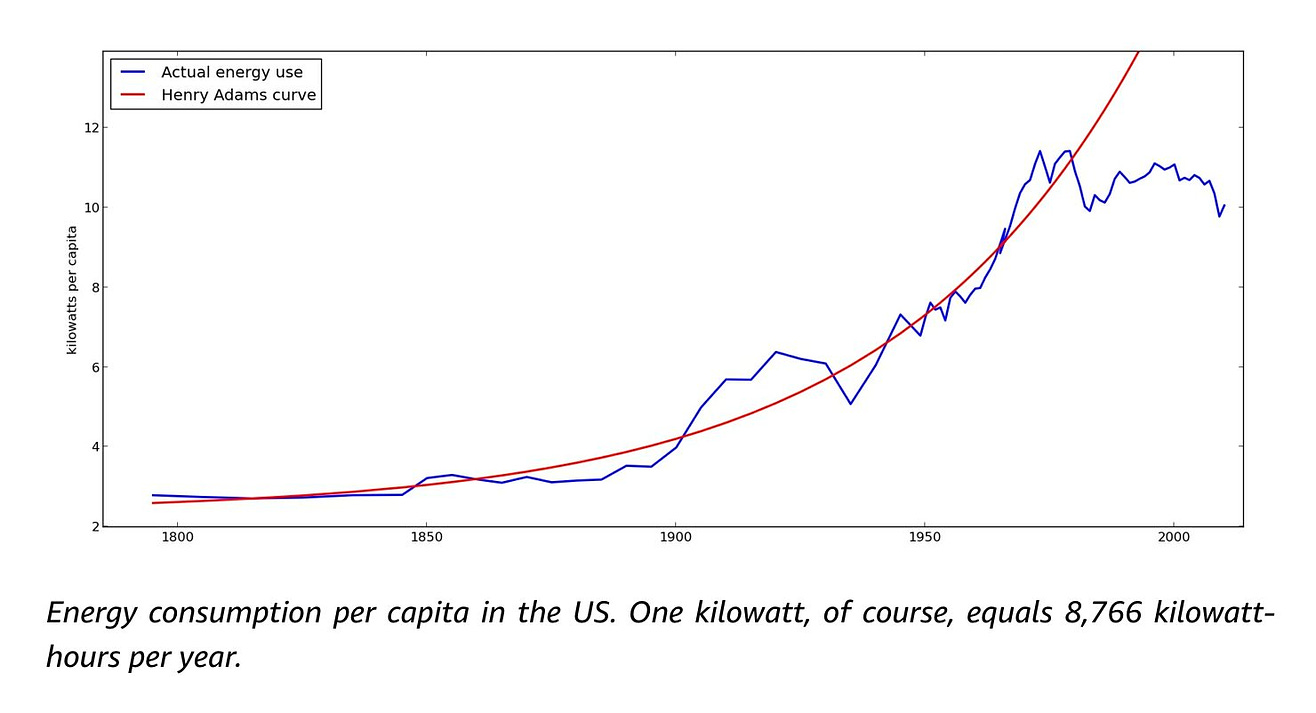

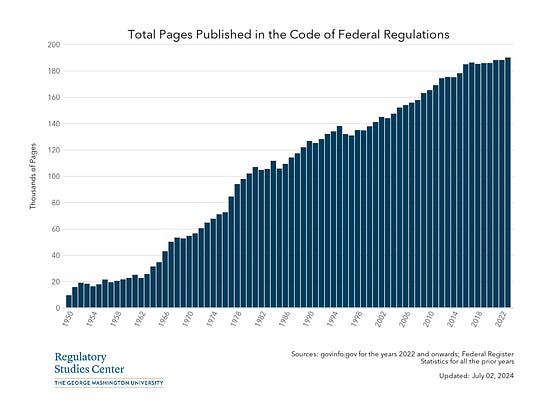

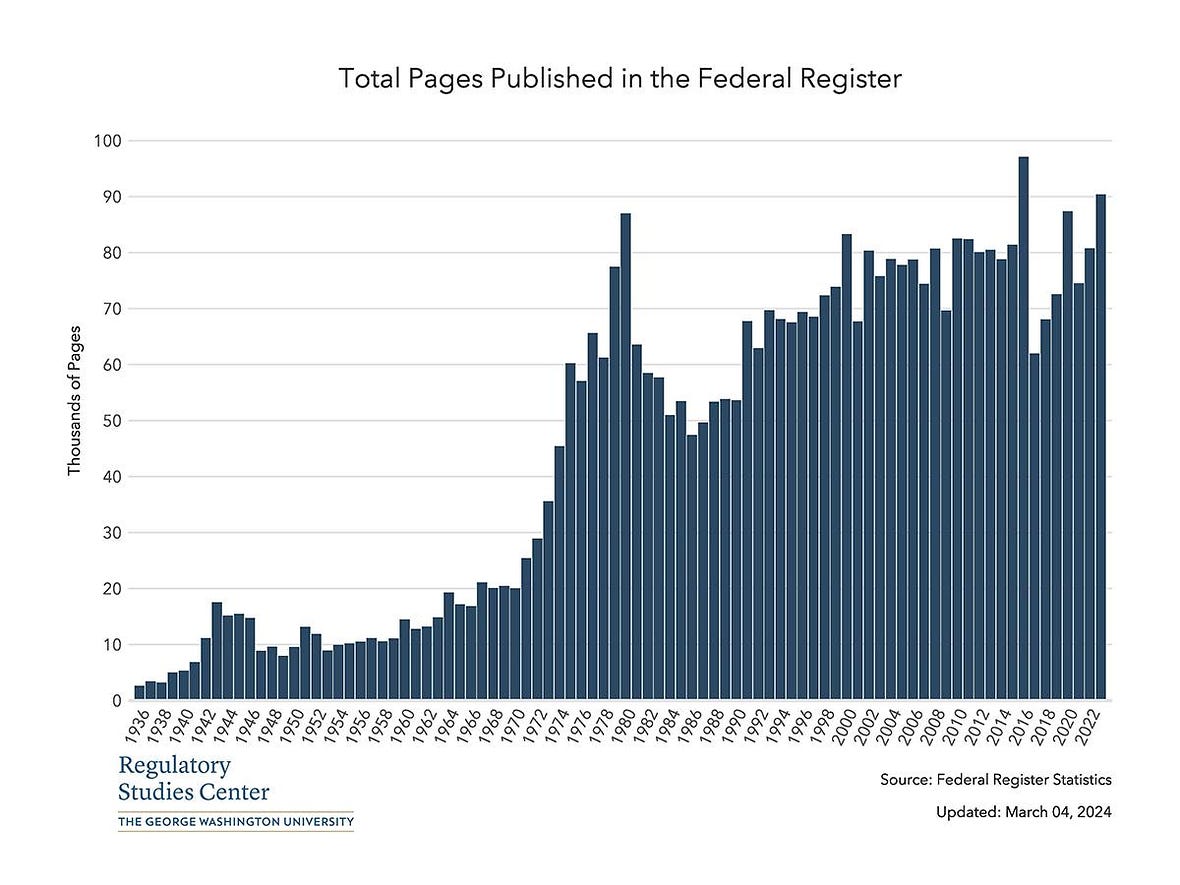

Here the person I talked to wasn’t as concerned about fighting destructive regulation (which mostly has yet to materialize) as using legislation to guide the technology on the right path. Self-driving taxis have a big advantage over self-driving self-owned-cars: they can operate 24-7 and never have to park. If you can switch half the car-using population to robotaxis, you can convert half the parking lots into green space or homes. Nobody wants to ban self-driving car ownership, but some people do want to nudge the marginal commuter into robotaxis so they can reclaim slightly-more-than-half of the parking lots instead of slightly-less. AirshipsNo matter how great our environmental or technological victories, they won’t feel satisfying unless we also have zeppelins. Luckily, some of the conference attendees were on the case. Public TransitThis wasn’t officially part of the conference, but at lunch somebody told me that the San Francisco legs of the BART - the Bay Area’s light rail, infamous for being noisy, dirty, and violent - had become comparatively safe and clean over the past few months, after the city installed fare gates that actually worked and couldn’t trivially be jumped over. Apparently the people ruining the BART for everyone weren’t even paying the fare. I always would have guessed there was a correlation between bad behavior and nonpayment, but am surprised at exactly how high the correlation has turned out to be (supposedly - I haven’t been on the BART myself recently to confirm). Again, this wasn’t part of the conference, but I thought it served as interesting commentary on the idea of Progress. WTF Happened In 2019I asked one question at the conference. It was about this graph: My question was: you talk about overregulation. But regulation has increased basically linearly, and this graph shows a switch from one constant regime to another. So what happened in 1973? The speaker said it was complicated, but mentioned a social shift from the techno-optimism of the 1960s to the techno-pessimism of the hippies and paranoid Nixonesque conservatives. The public consciousness rejected The Jetsons in favor of Paul Ehrlich, Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobs, and Ralph Nader, and this probably had downstream effects on lots of things, including regulation. After the conference I looked into this further, and - maybe my question was wrong! Cremieux believes most of the trends that seem to change shape in 1971 are measurement errors (click for link to explanation): This is plausible, since the modern inflationary regime started in 1971 and there are lots of ways inflation can mess with trend measurement. I need to look into this more. But I start out suspicious: kilowatts don’t inflate, and the Henry Adams curve looks like all the others: My question might have been wrong in another way too. I said regulation went up linearly. According to the measure of regulation I’ve always seen before, Total Pages Published In The Code Of Federal Regulations, this is true: …but another, Total Pages Published In The Federal Register, shows a more suspicious pattern: And everyone’s favorite punching bag, NEPA, was signed on January 1, 1970, which is almost too perfect. I find this interesting, because I sort of mocked the last Progress-Studies-esque mini-conference I went to. The Gods of Straight Lines are mighty and dreadful; it takes immense hubris to believe one can wrest them off their predestined path. I described the goal of this conference, now six years past, like so: And now I feel less like mocking this. There’s still no visible kink in total factor productivity, let alone Moore’s Law. It could still all be hype. But the report from these people, who have spent half a century on the losing side of every battle, is that things are starting to look cheerier. Congress understands the problems with NEPA and is at least considering making life easier for the solar plants. Suddenly everyone’s a YIMBY. The first small modular nuclear reactor has been approved. But more than that, there’s suddenly awareness. It might seem like nothing could be more obvious than the idea of “wait, we fell off this growth curve and now we’re twice as poor as we need to be, maybe it’s all the growth we’re blocking”. Or “wait, we basically made it illegal to build houses and now the American dream of homeownership is critically endangered”. But the first organized YIMBY movement was in the mid-2010s. The term “Great Stagnation” first got used in 2011. The Henry Adams Curve was first published in 2021. It feels like the United States, after a fifty-year binge on over-regulation, has woken up, wiped the vomit off its chin, noticed it’s lost half its net worth, and started to consider doing something else. I am equally confused why it took so long and why it’s happening now. Most of the victories discussed at the conference have nothing to do with Progress Studies. The solar industry, the self-driving car industry, etc, don’t even know it exists. Even the YIMBYs, whose leading representatives did attend, predate the field. My theory is that it all came from the same wellspring. Silicon Valley gathered all the pro-tech people together in one place, a lot of them became rich, and some of them spent their wealth reflecting on the nature of technological advance. This created a critical mass of people who were all talking to each other and motivated to see things that other people were missing. This isn’t the whole story: non-Silicon-Valley economists like Paul Krugman and Larry Summers helped build the foundational narrative. But it’s the story that makes the most sense for “why now”. I mocked the people in 2019 who thought a conference could affect the Gods Of Straight Lines. But it seems like maybe there was something - an idealized spiritual conference in 1971 between Ralph Nader, Jane Jacobs, Rachel Carson, hippies, protectionists, and all those people - who knocked them off their thrones once. So who knows? I’m definitely making the same mistake of which I half-accused Tyler Cowen - going off vibes in a notoriously difficult field. But at least at this conference, the vibes were good. You're currently a free subscriber to Astral Codex Ten. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Older messages

Secrets Of The Median Voter Theorem

Wednesday, October 23, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

ACX Local Voting Guides

Tuesday, October 22, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Open Thread 352

Monday, October 21, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Open Thread 351

Sunday, October 20, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

AI Art Turing Test

Sunday, October 20, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

You Might Also Like

It’s a great moment for startups — with one caveat | Microsoft retiring Skype

Friday, February 28, 2025

Meet the new leader of Alliance of Angels | Amazon commits $100M to Bellevue for housing ADVERTISEMENT GeekWire SPONSOR MESSAGE: SEA Airport Is Moving from Now to WOW!: Take a virtual tour of

S*M*A*S*H*

Friday, February 28, 2025

Measles and Maha, Putin's Pawn ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

DOGE is operating in near-total secrecy. We’re about to break it wide open.

Friday, February 28, 2025

Under the Freedom of Information Act, the public has a right to access documents and other information that will shed light on DOGE's operations, and we're committed to getting to the truth.

TFGIF: ♻️ In Trumpland, it ain’t easy being green

Friday, February 28, 2025

The fight for the soul of the battery belt and the other C-word. Welcome to Lever Daily's TFGIF. Each Friday, we share one deep-dive Lever story and one deep-dive podcast episode full of original

☕ Wait and DTC

Friday, February 28, 2025

Bonobos's new ambitions. February 28, 2025 View Online | Sign Up Retail Brew Presented By Brookfield Properties Hi there. This week, Amazon dropped a new Alexa upgrade powered by (you guessed it)

Debunking some myths about Tangle (and me).

Friday, February 28, 2025

Let's talk about why we are here. Debunking some myths about Tangle (and me). Let's talk about why we are here. By Isaac Saul • 28 Feb 2025 View in browser View in browser Photo by Nijwam

Decisive Moments, Creative Playbooks and Who Is Really Watching TV?

Friday, February 28, 2025

10 stories that have given us creative inspiration this week

Everything-Except-Book Review Contest 2025

Friday, February 28, 2025

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

GeekWire Startups Weekly

Friday, February 28, 2025

News, analysis, insights from the Pacific NW startup ecosystem View this email in your browser Presented by Seattle-Tacoma International Airport New head of Alliance of Angels excited to hit '

Tokyo Bayes

Friday, February 28, 2025

Writing of lasting value Tokyo Bayes By Caroline Crampton • 28 Feb 2025 View in browser View in browser 10 Observations About Tokyo Quico Toro | Persuasion | 19th February 2025 American resident in