|

This is quite a long post, so may be best viewed in your browser. Mike Meyer once told me the story of some small talk he had at a border control point. The conversation went something like this: Officer: So, what do you do for a living?

Mike: I'm a sign painter.

Officer: What's that then?

Mike: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

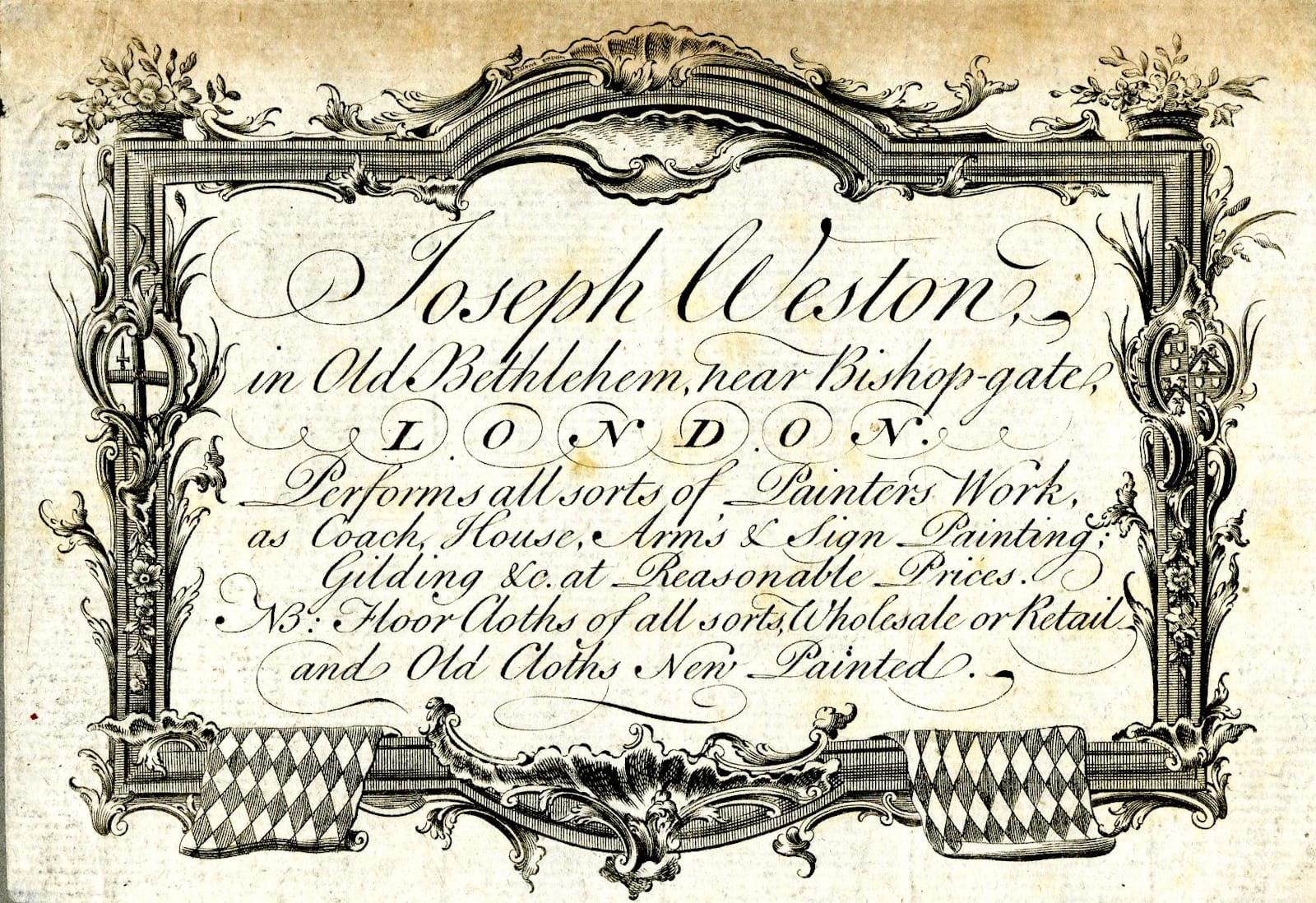

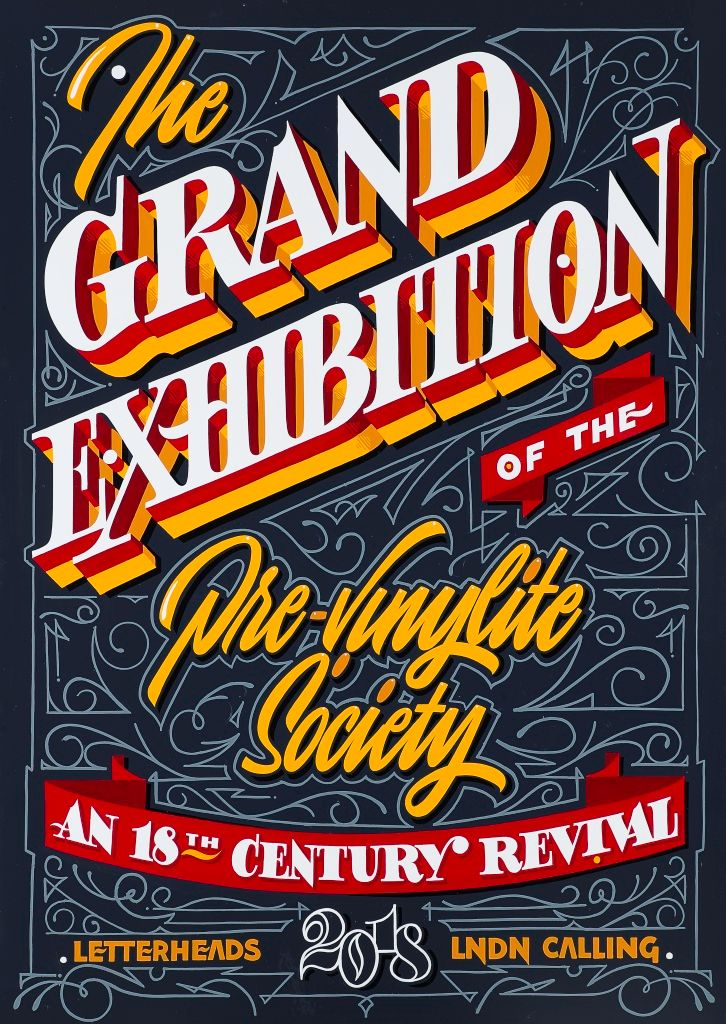

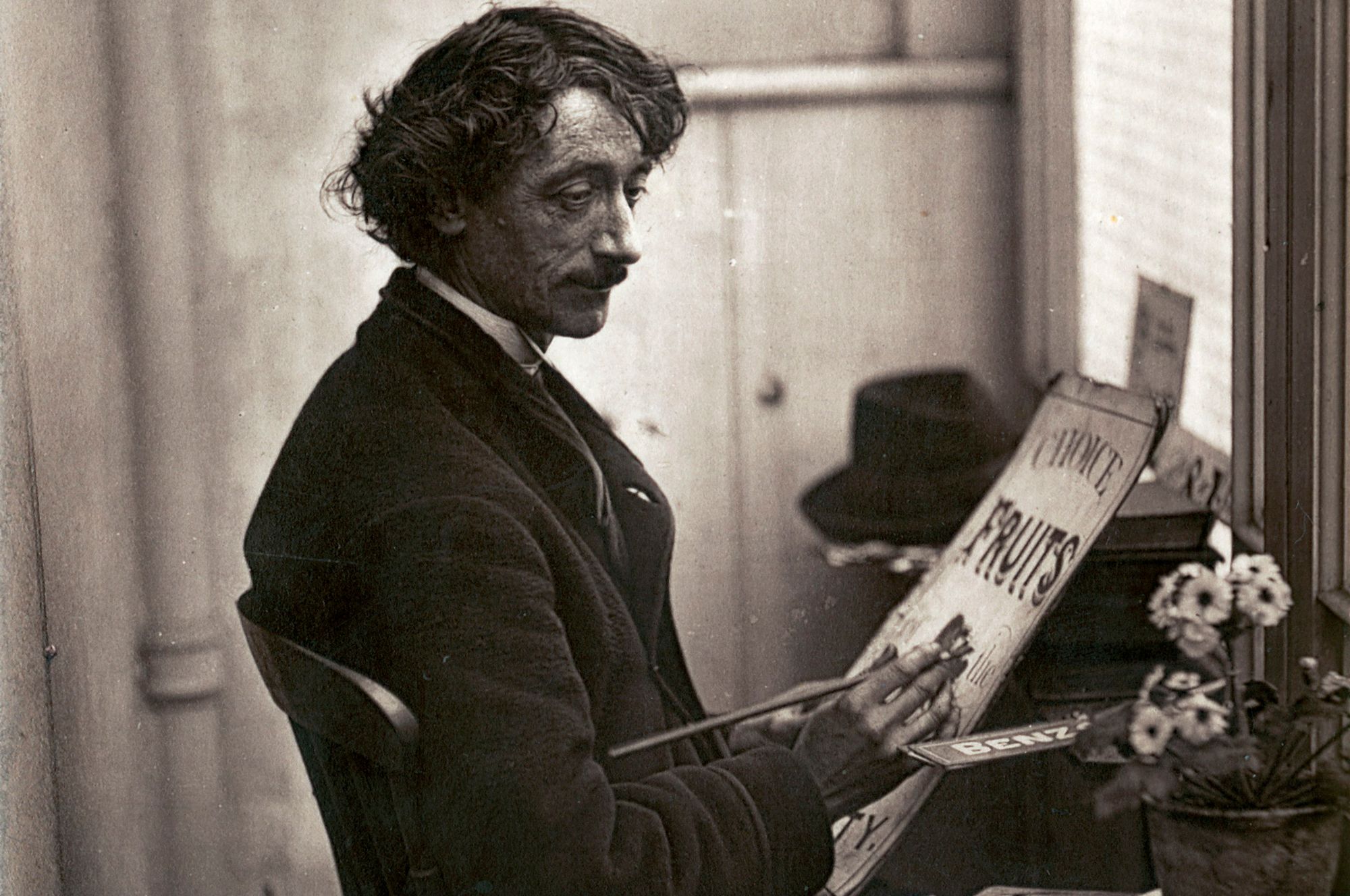

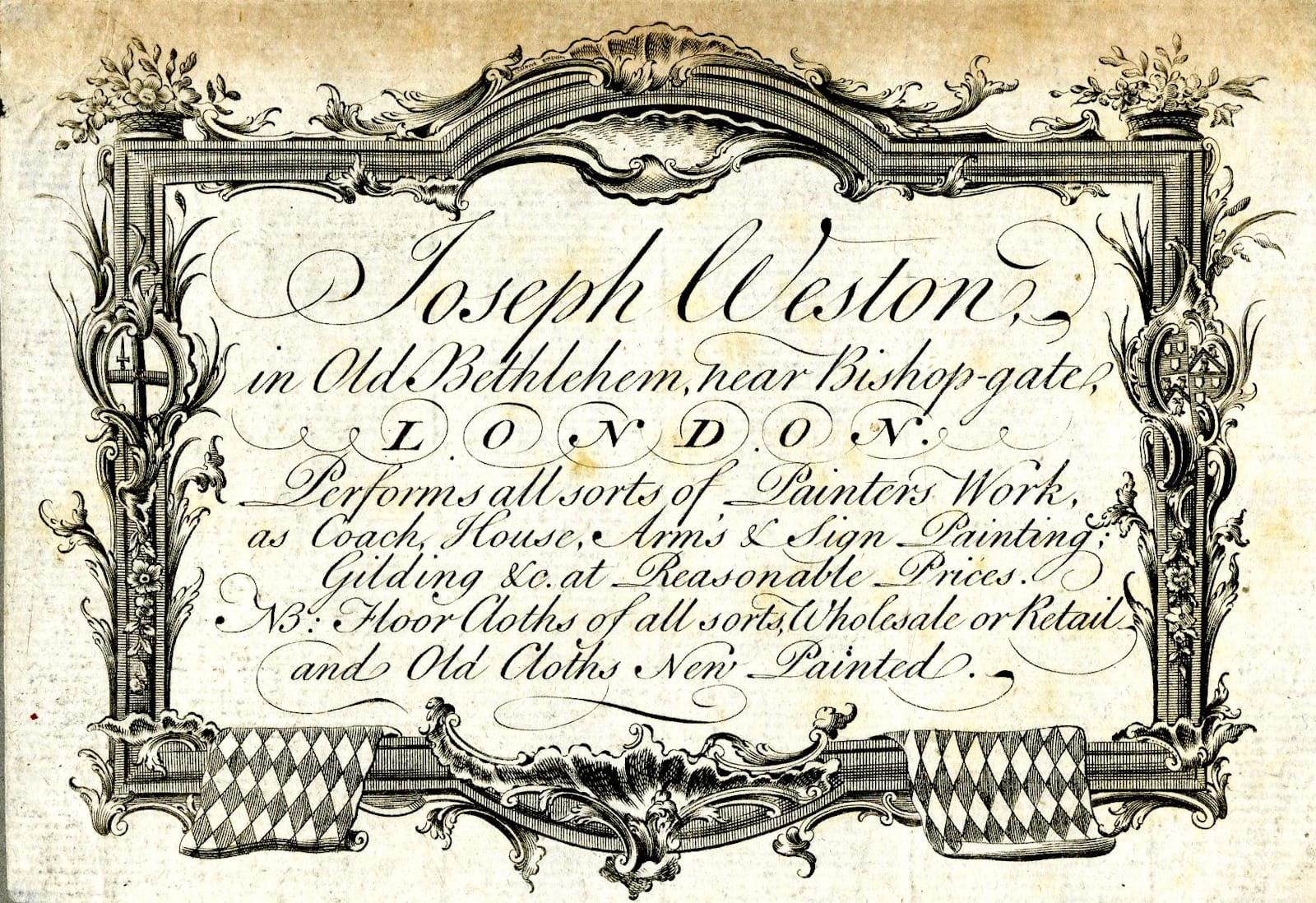

Despite the very literal and descriptive nature of the term, it seems that not everyone can deduce what would seem obvious: that a sign painter paints signs. Perhaps this stems from the common misconception of sign painting as 'a dying art'; most sign painters have heard something along the lines of 'you don't see much of that about any more' while painting. But is there more to the name of the trade, and its practitioners? The simple answer is 'no', but I thought it would nonetheless be interesting to look at its emergence, and current usage. The Second Oldest ProfessionI can't remember who quipped that sign painting is the second oldest profession, but there is a connection to the first at the ruins in Pompeii. Painted in 79AD, or earlier, this advertisement for a brothel is not the only example of commercial signage painted on walls there. It is largely accepted, thanks to the work of Edward Catich, that Roman inscriptions were first painted onto stone using a flat brush. This brushwork also extended to pieces that were never going to be carved: painted lettering remains at Pompeii and Herculaneum in the form of commercial and political communications. So the craft does have some history behind it, but maybe 'second oldest profession' is pushing things just a little. Painters Turned Sign PaintersFast forward to the eighteenth century, and sign painting was once again alive and well in Britain. Pictorial painters were found painting signs, using this to provide, or supplement, their incomes. The building trades, notably painter-decorators, plumbers and glaziers, also applied themselves to the craft. There is a very British focus to this discussion and I am well aware that other countries have other traditions. However, Britain is where most of my sources originate, and it does have particular relevance as the first major industrialised nation. Due to lower literacy rates, signs were usually pictorial, and producing them required artistic rather than lettering skills. In this sense, the artists and tradespeople were very much painters, of signs among other things, and this terminology is found on trade cards from that time.  This painter's trade card from the second half of the eighteenth century reads: "Joseph Weston in Old Bethlehem near Bishop-gate, London, Performs all sorts of Painters Work as Coach, House, Arms & Sign Painting, Gilding &c. at Reasonable Prices. NB: Floor Cloths of all sorts, Wholesale or Retail and Old Cloths New Painted." Image © The Trustees of the British Museum. One of the most famous eighteenth century painters that turned his hand to sign painting was William Hogarth. He also had a role in the satirical 1762 Grand Exhibition of the Society of Sign Painters. These days, sign painters come from many different backgrounds, artistic and otherwise. Early graphic designers referred to themselves as 'commercial artists' and still there are those that prefer 'graphic artist' to 'graphic designer'. Similarly, there is a distinction made between 'fine' and 'applied' arts, with one often seen as more prestigious than the other. This hierarchy is nothing new, and was present in, and before, the eighteenth century. Sign Painting: Art, Craft, or Both?This is one of the enduring questions about sign painting, and can lead to some fascinating discussions and debates. The title of Tony Lewery's Signwritten Art suggests that the output of sign painters can be classified as art. He makes the case for a subset of painted signs being considered 'folk' art, but doesn't see art and craft as mutually exclusive: "Art is about the emotional response, craft is the practical handling of materials and techniques. Happily the two are so often involved and interdependent that this separation is quite unnecessary."

He also teases this apart a little with respect to high craft: "It happens that a good craftsman will often go beyond that [producing an acceptable job] and, perhaps unconsciously, produce work that meets all the requirements of a work of art as well. He is then an artist as well as a craftsman, but it would be wrong to say that another workman, who cannot reach that art standard, is not therefore a craftsman. It is equally wrong of course to assume that fine craftsmanship is necessarily good art."

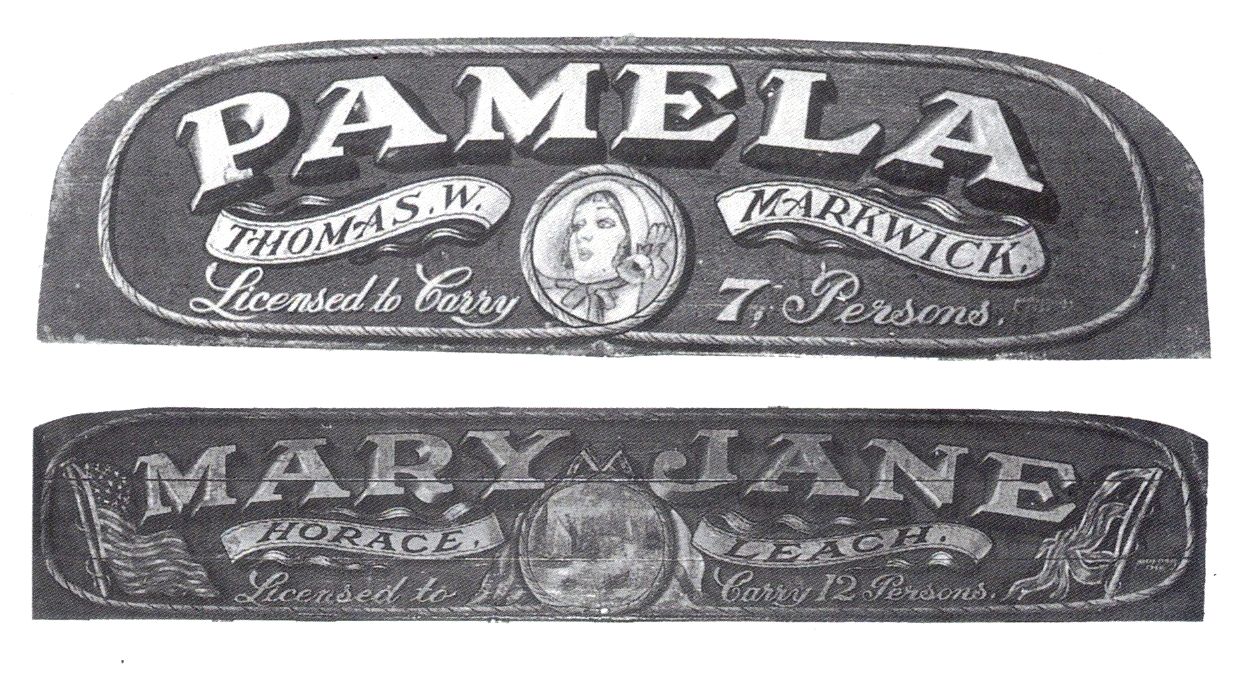

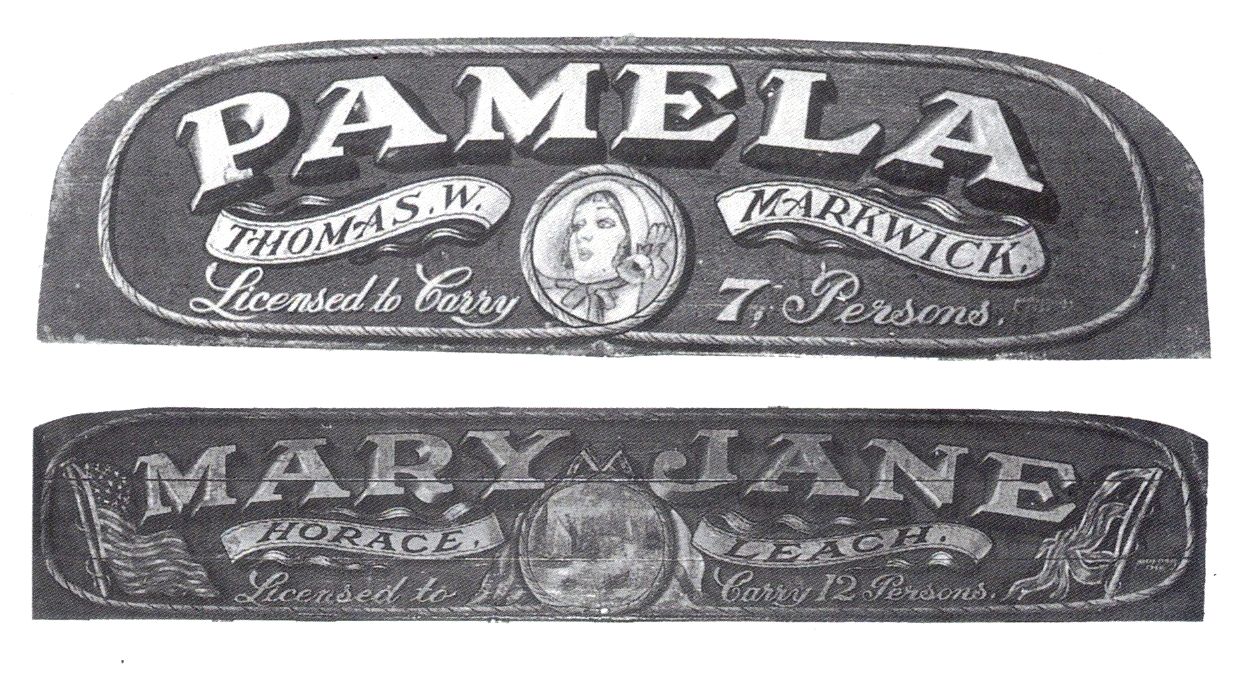

From Signwritten Art by Tony Lewery: "Two 'backboards' from Brighton fishing boats, which were effectively backrests for the stern seats when these local rowing boats were briefly converted to tripper boats during the summer season. The owner's pride is evident, as is the old-fashioned skill of the local signwriter Harry Taylor who painted Mary Jane's board in 1948 and Pamela's in 1952. These perfect examples of signwritten folk art are now preserved with several others in the local fishermen's club." Clearly, painted signs can be produced with high levels of artistry, and purely artistic works can employ high levels of craft in their execution. However, a potentially important distinction is who the work is being produced for. In Sign Painters, the Minneapolis sign painter Forrest Wozniak explores this: "One of the biggest differentiating factors of signs is that there is a wrong way to do it. Art naturally can subject itself to abuse 'coz there isn't necessarily a truth to art. Because you're pursuing yourself. You're pursuing an exploration of your ego... and there isn't really a right or wrong. [With] Signs, you're pursing the ego of your client, and the truth behind letter formation, so there is a right and a wrong."

This doesn't contradict Tony Lewery's remarks, but it does introduce the important role of clients, or patrons in the case of 'pure' artists. Every sign painting job has, or should have, a brief. This dictates certain requirements, and potentially the degree of freedom or artistic expression that can be employed in painting the sign. The extent to which it will be 'art directed' by the client can be visualised as a spectrum, humorously expressed via this pricing meme. Design PricesI Design Everything — $100

I Design, You Watch — $200

I Design, You Advise — $300

I Design, You Help — $500

You Design, I Help — $800

You Design, I Advise — $1.300

You Design, I Watch — $2,100

You Design Everything — $3,400

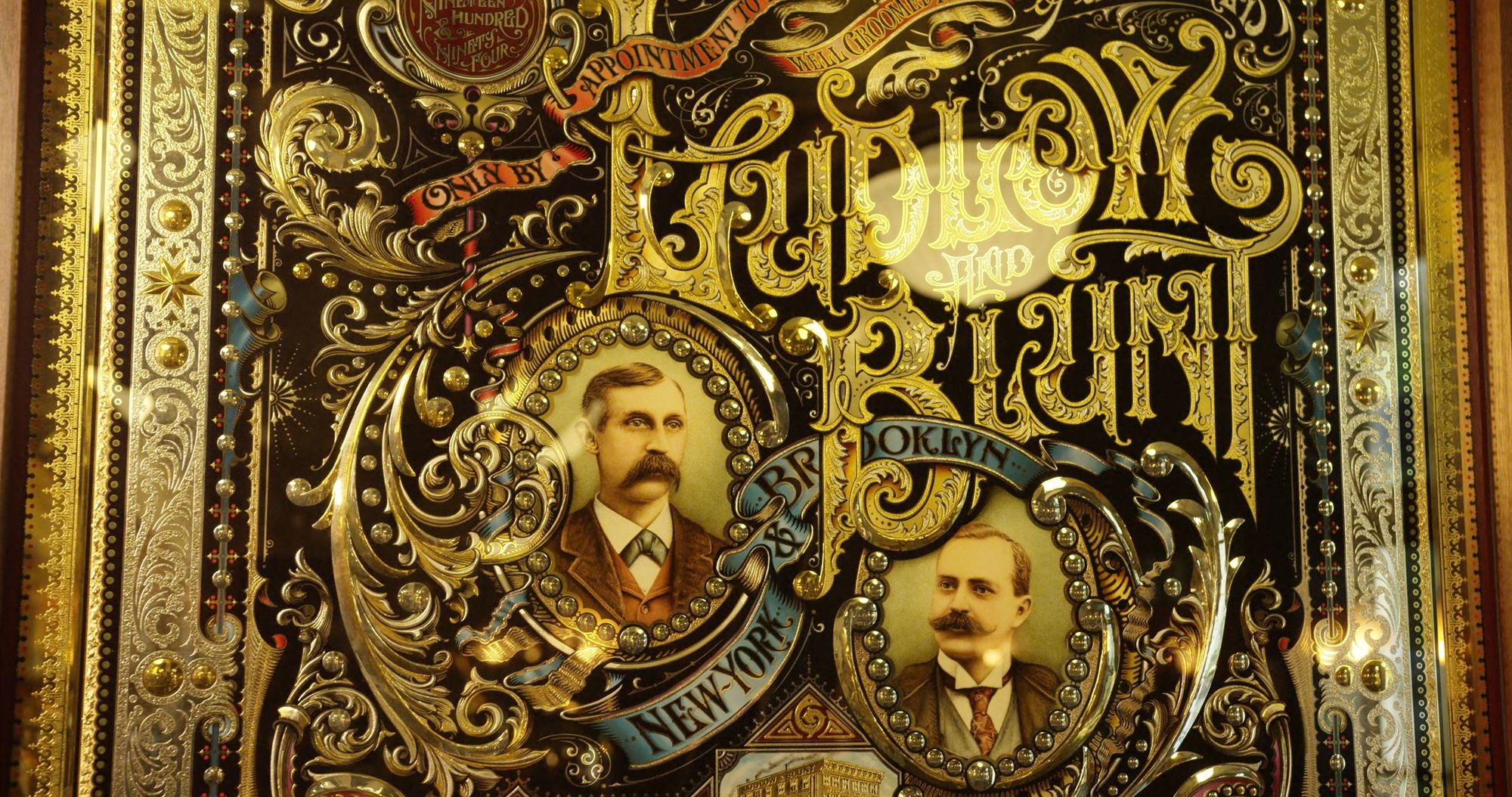

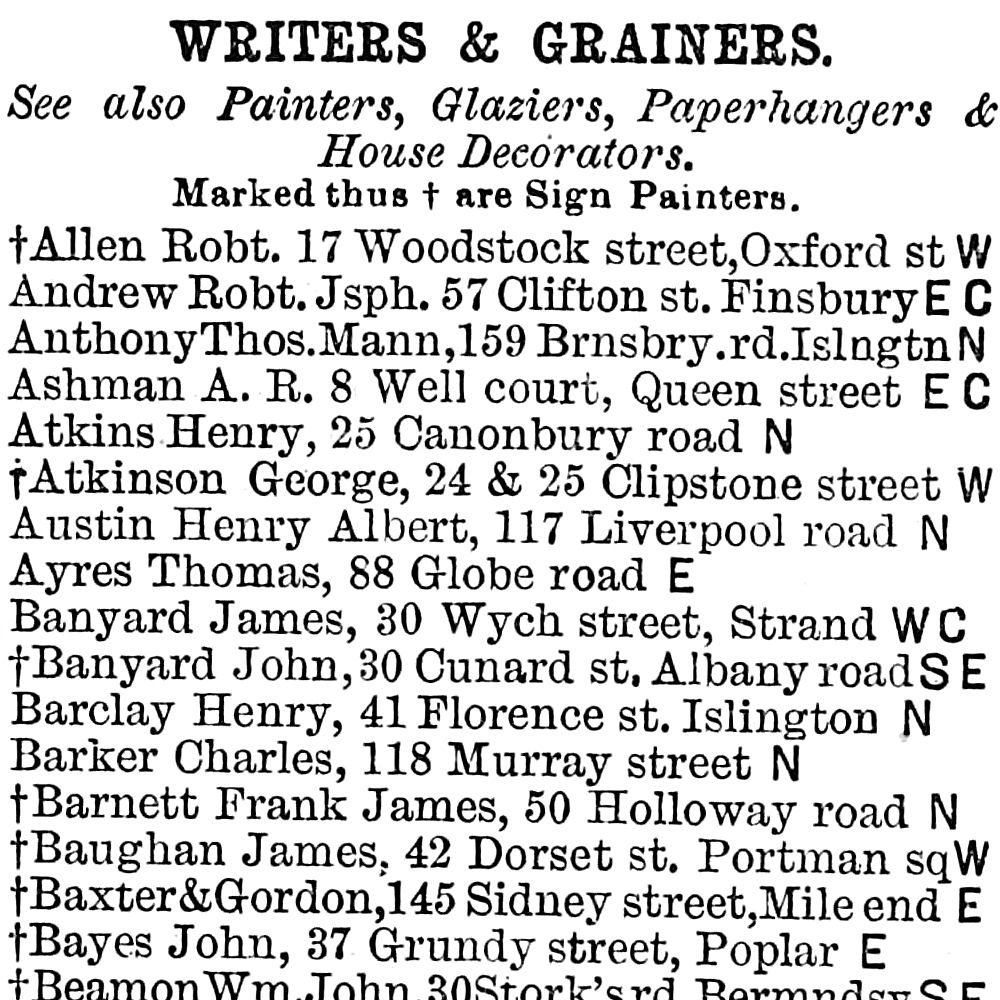

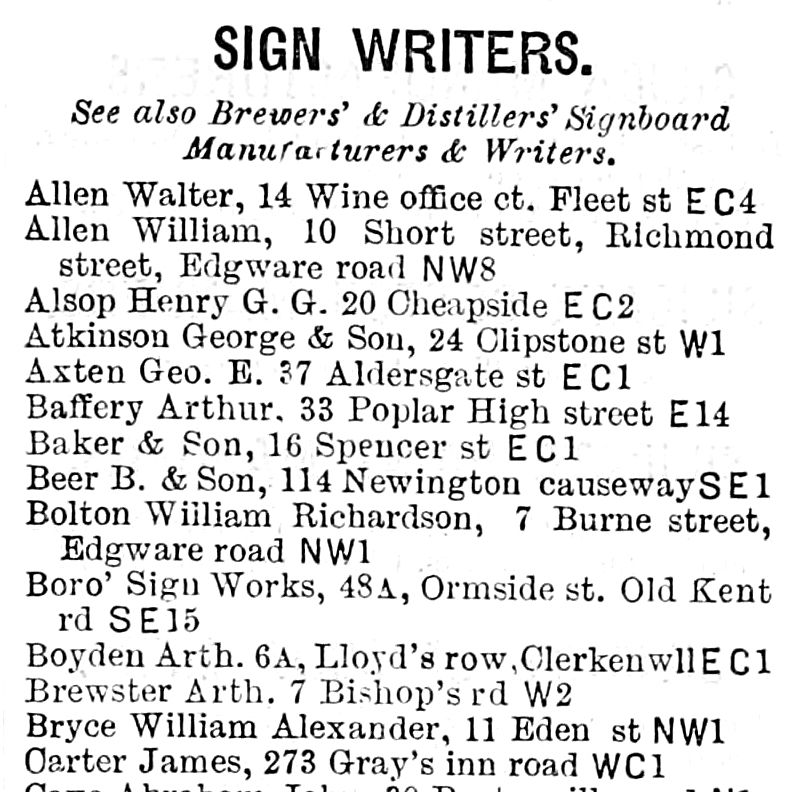

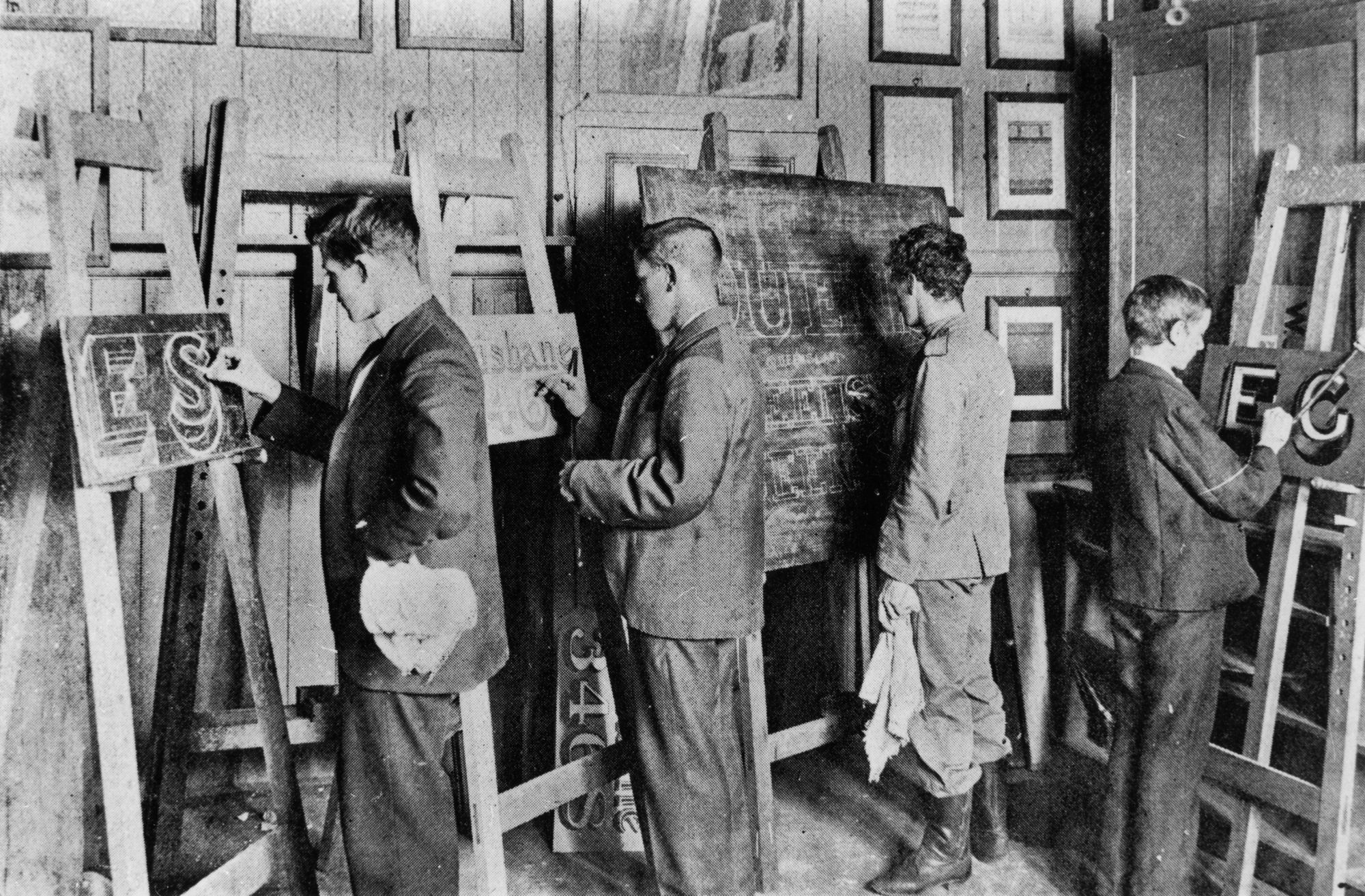

If client involvement exists along a spectrum, then perhaps art and craft can be thought of as a Venn diagram: work can be placed exclusively on either side, or in the overlapping middle when it is considered both art and craft. What goes where is clearly subjective, but for starters we could consider David A. Smith's work for Ludlow and Blunt... Sign Painting vs SignwritingIt seems that the use of 'writing' to describe sign work began in the nineteenth century, at least in Great Britain. This was in response to the increasing use of words on signs as literacy rates rose. London trade directories from 1895 (left) and 1930 showing the emergence of the term 'sign writer'. Nineteenth century trade directories list those practising the craft as 'writers' and 'writers and grainers', while differentiating those doing 'sign painting' work within these classifications. It wasn't until the 1920s that 'sign writers' began to gain prominence, as discussed in the 'Sign Production' chapter of Ghost Signs: A London Story. In parallel, other English-speaking countries have followed different paths. While 'signwriting' is the term most widely used to describe the trade in Ireland, Australia and New Zealand, it is often abused to describe any form of sign making, whether with the brush or otherwise. Those in the USA have largely stuck with 'sign painting', which is more literal and neatly encompasses the diversity of work undertaken in the trade—'signwriting' potentially limits this scope to just lettered signs, excluding pictorial or decorative work. Sign Painting DisciplinesIn addition to the 'painting/writing' distinction, there is also the question of which techniques fall under the banner of sign painting. A literal interpretation would limit this to just the painting of signs. However, there are myriad other techniques employed by sign painters. Graining, marbling, and coach lining all use brushes and paints, sometimes on signs or vehicles, but typically for purely decorative purposes. The disciplines of showcard and ticket writing often use pens in addition to brushes when creating signs. And techniques such as gilding and screen printing are regularly employed by sign painters, introducing a range of different materials and skills to their portfolios. Each of these techniques pushes the core idea of 'sign painting' beyond what can be produced with brush and paint alone. They blur the boundaries of the craft, and offer a more holistic conception of what it involves. Clearly not every sign painter is adept in all of these skills, but a large number work across more than one of them. So, What is Sign Painting?This is what the current Wikipedia entry says: "Sign painting is the craft of painting lettered signs on buildings, billboards or signboards, for promoting, announcing, or identifying products, services and events." — Wikipedia, 23 October 2024

This usefully builds on the self-referential 'sign painting is painting signs' that flummoxed the border official at the start of this piece, but lots of the nuance in the discussion above is lost. For example, it fails to include pictorial work and signs that aren't commercial in nature. I'll therefore take the following stab at an alternative: "Sign painting is the craft of producing lettering, pictorials, and decoration for signs using predominantly brushes and paints."

What do you think? I'm ready to be shot down in the comments 😄

Join BLAG on the most popular annual Blagger plan before the end of October and save $30 on the usual price. This includes BLAG 05 sent straight away to wherever you are in the world, and the knowledge that you're supporting independent, advertising-free publishing.

Further Reading

|