|

Roscommon is a small town in the centre of Ireland and home to Irish Mosaics, a business whose output reaches across, and well beyond, the island. Ahead of a piece about her own adventures in mosaic making for BLAG 06, Vanessa Power caught up with Thomas Kilroe who has been plying his trade in tiles for over 60 years. Now semi-retired, he offers his reflections on a life in tesserae.

BLAG 06 is currently being bound, and will ship exclusively to members worldwide from 2 January. If you'd like to be on the distribution list, and get BLAG 05 before that, then join today with $20 off the popular annual Blagger plan.

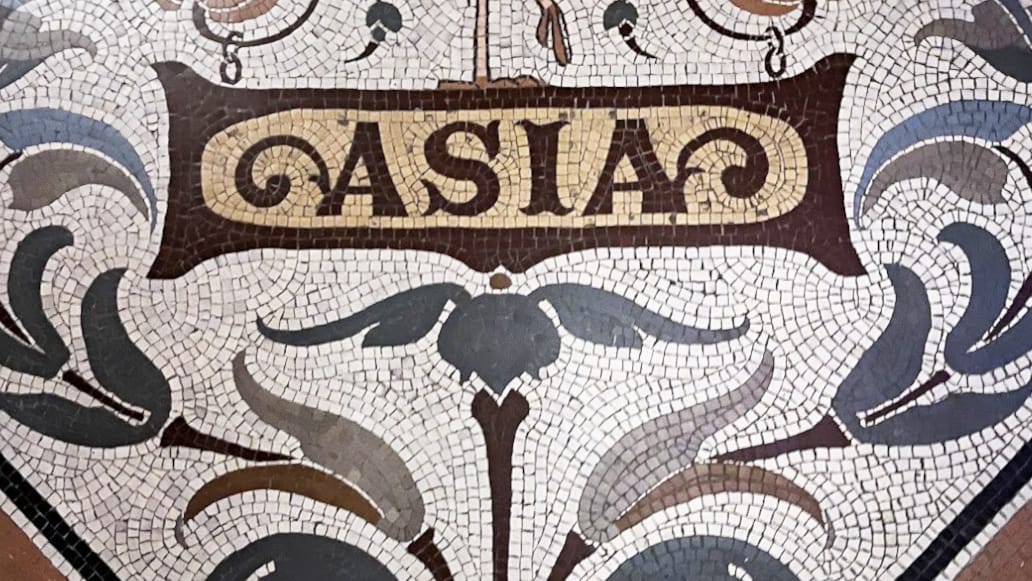

Irish Mosaics: From Roscommon to the WorldBy Vanessa Power Mosaics are a distinctive, charming feature of the Irish urban landscape, but for many years they were imported into the country. That changed in 1954 when John Crean, alongside craftspeople brought over from Italy, founded Irish Mosaics in Roscommon. His vision was to blend traditional Italian techniques with modern designs to advance the art of mosaics in Ireland. Some classic Irish mosaics blending lettering, pictorial, and decorative elemtns. The Mullaney Bros. and Lyons Cafe entranceways are in Silgo, while those for Ryan's and the Stag's Head are in Dublin. The Stag's Head is one of Dublin's most famous mosaics and was restored by Irish Mosaics. Irish Mosaics' work was commissioned for use in various settings, including private homes, public spaces, and religious buildings. In addition to its work in Ireland, the aesthetic appeal and cultural significance of the company's creations led to major projects for the export market. In a business traditionally dominated by Japanese, Italian, and some English makers, John Crean supplied and installed mosaics in Australia, England, Nigeria, and the USA. Enter Thomas KilroeThomas Kilroe joined Irish Mosaics as an apprentice straight after finishing school, and went on to run the company. He continued the legacy that John Crean began, crafting bespoke mosaics for homes and businesses across Ireland. His mosaic art projects enhance both public and private spaces, including churches, schools, pubs, shops, hotels, and community spaces.  A 24-hour sundial mosaic by Thomas Kilroe/Irish Mosaics. Everything is produced in reverse on backing paper, which is then removed after the finished mosaic has been transported and flipped over onto the adhesive during installation. Kilroe's mosaics are renowned for their artistry and the stories they convey through the meticulous arrangement of carefully cut tiles. This timeless beauty and cultural significance have made many of his entranceway mosaics in Dublin pubs and shops treasured landmarks of the city. I was lucky to meet him recently, and had the opportunity to ask some questions. Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you got started in mosaics? My name is Thomas Kilroe. I went to school with two of my best friends, whose father started a mosaic business in the fifties. By the time I saw it, it was already well-established. Spending time with my school pals and witnessing the beautiful work being done, I became fascinated and couldn’t wait to finish school and start working there. Growing up on a farm, this seemed like a far more appealing option than farming.

How did you begin your professional journey in mosaics? I started an apprenticeship with Irish Mosaics. I was fortunate because the Italians working there, particularly Luciana de Paoli, became my mentor. As I progressed, he gave me more intricate work, always encouraging me. Romeo Vasistello specialised in the fixing end of the mosaics. In the sixties, there was a lot of church work with new churches being built. I nearly served my time with the five rosary churches in Cork: Wilton, Mayfield, and others. It was wonderful because now you wouldn’t have the opportunity to do such large-scale mosaics.

What kind of projects have you worked on in recent years? For the last 20 years of my working life, I mainly did restoration. In the National Museum and the National Library. The cathedrals, churches, and chapels, like the Mater Hospital chapel in Belfast and the Good Shepherd Convent in Belfast. I worked on six churches or chapels and two cathedrals in Belfast. The church work was my favourite.

These mosaics at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin were originally produced in the nineteenth century by Manchester-based artist Ludwig Oppenheimer. They were then covered for decades until being cleaned and restored in by Thomas Kilroe in 2011. How did changes in the industry affect your career? I worked for Irish Mosaics, but then the boss died, and the regime changed. They had very little interest in the art. They bought it to use up the materials. They got their money back from me doing that, but I had no time for it and started moving out. When work became scarce, I took little subcontracts from various people in the mosaic, tiling, and terrazzo business, mainly in Dublin. A lot of it was very commercial, like doing panels on the facades of buildings and shop fronts.

Can you share some unique projects you've done over the years? I did work for the Irish Pub Company, doing mosaic doorways, behind the counter, sometimes the front of the counter with the pub's name, and a graphic element like a Celtic design. Guinness designs too, until they asked us to work for them.

Irish Mosaics project with lettering elements. What is your approach to creating mosaics? Sometimes I work from designs the client presents. If they want me to come up with a design, I do the design, enlarge it, and draw it on the paper in reverse. Then I use my hammer to make it up. In recent years, I don't install them myself: I present the mosaic to the clients, packaged for their tradesmen to fix. But in the old days, we did the entire thing. Few of us did all the art, the craft of putting the tesserae together, and the trade of fixing it in place. At 81 years of age, I regard it more as a hobby now. I wouldn't take on any big jobs. I've had a good innings.

Created for a television commercial, the Bulmers tagline—‘Nothing added but time’—was particularly fitting for the mosaic-themed ad. This was doubly so, as Kilroe actually had to create the lettering on the bottle twice. He'd initially peeled the label off a bottle to use as a reference for drawing the letters, but once the mosaic was finished, he noticed the lettering was off because the logo on the label had been slightly tapered to fit the curve of the bottle. This meant the mosaic didn’t translate correctly, and he had to start over. What is the most enjoyable part of the process for you? Deciding how to go about doing it. The planning. Waking up and reimagining the design. Sometimes changing it and starting again.

Is there a piece in your portfolio that you're most proud of? There are so many. As a young man, I got a kick out of learning and seeing the job done, thinking it would last 20 years. Now, 60 years later, I'm still looking at them. They last too long.

One of Thomas Kilroe's first mosaics from his days as an apprentice, which still looks fresh all these years later. What kept you motivated throughout your career? Job satisfaction is a big part of it. I could have made more money doing other things, but my mother let me stay in school, which stood to me in other ways. I even went back to study in my forties, doing a course at the Irish Management Institute. But mosaics were my passion. I had to get back to it even after working with Wagstaff & Wilson, a jewellery wholesale company. I became the branch manager but decided it wasn't for me and went back to mosaics.

Did you mentor anyone in the field of mosaics? I had about four different apprentices over the years, but they weren't as lucky as I was to have someone with great experience. They might be good at the trade, but I was fortunate to work with top-class people.

Do you have any tips for people looking to get into mosaics? The same tips I'd give to anyone becoming a painter or sculptor: dedication and patience. Look at lots of mosaics, see the good ones, and learn what makes a good mosaic.

Any advice you'd give your younger self? Would you change anything? No. I've been lucky, first with my mother letting me finish school, then meeting the right people. I got the opportunity to travel to America and work, but I'm happy to point to all the work I've done over the years.

Excellent. What's next for you? I might start a small sketch in the morning and expand on it. Just keep doing what I love.

Thomas Kilroe in his happy place, setting down tile after tile for his next creation. Article and interview by Vanessa Power / @signsofpower

More PeopleMore History

|