Editor's note: We are off for President's Day today, but have a special edition featuring a guest writer today. Core to our mission at Tangle is offering perspectives from influential and thoughtful voices from across the political spectrum. As we've grown, our ability to advance that mission has also grown, allowing us a broader reach and new ways to offer coverage of political news to our subscribers.Today, we are pleased to publish a thoughtful essay from Jacob Sullum, senior editor at Reason, about President Joe Biden's and President Donald Trump's recent acts of clemency.We hope you enjoy it — reply to this email or comment to let us know what you think! What’s your caffeine cutoff? There’s a moment when caffeine stops being a boost and starts being a liability. If you’re already on edge about democracy, it might already be a bit challenging to sleep — why make it worse with that extra cup of caffeinated coffee? You’d do decaf, but it sucks right? Maybe not anymore. We used to think decaf was coffee that tasted like disappointment and regret — until our friend Matthew (who also happens to be the designer behind Tangle’s recent site redesign) started Wimp Decaf. Turns out if you source better beans, and decaffeinate naturally, great decaf isn’t just possible; it’s a game-changing and delicious. Full specialty coffee flavor, zero toxic chemicals, zero hyper-drive when you’re ready to rest. 🚨Tangle readers get 3 bags for $59 (save up to $14) when you buy 3 bags or more. (Hint, freeze whatever you don’t need right away). Last time we ran this ad, Wimp sold out of coffee. They’re well stocked, but don’t tempt fate!

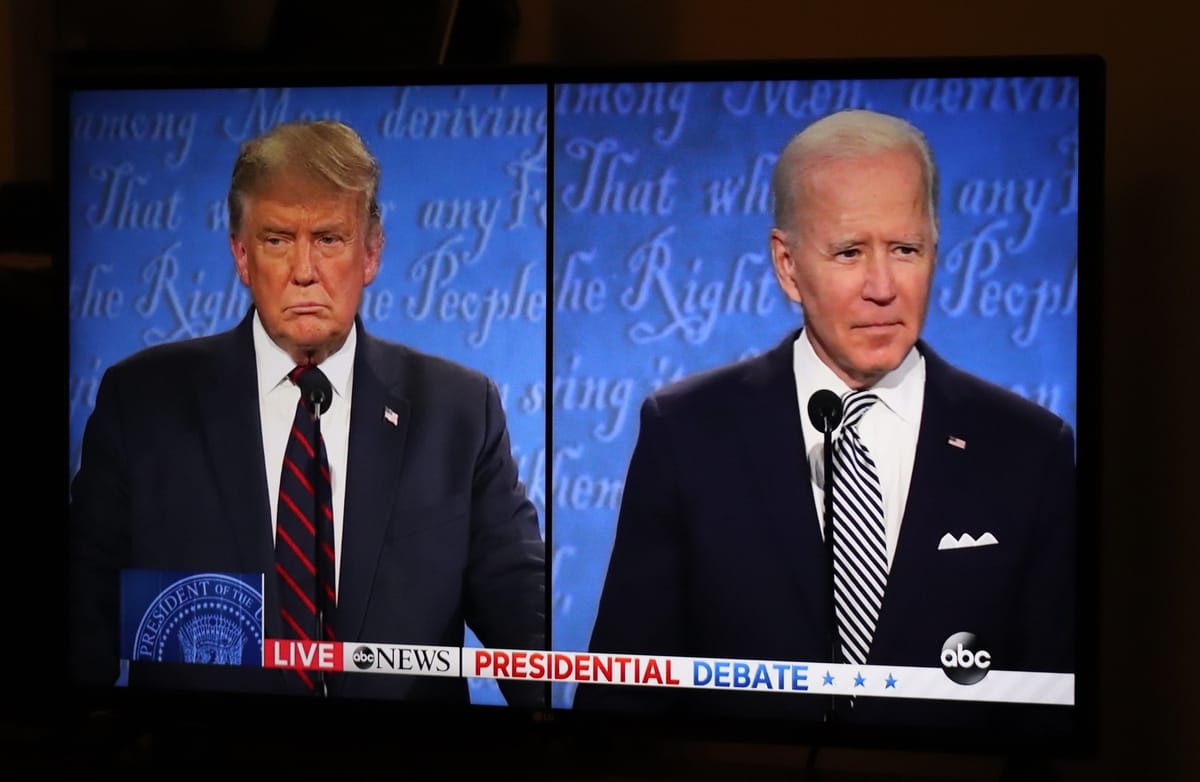

By Jacob Sullum During his 2020 campaign, Joe Biden said he would “use the president’s clemency power to secure the release of individuals facing unduly long sentences for certain non-violent and drug crimes.” He ultimately delivered on that promise in a big way, commuting 4,165 sentences by the end of his term. That total far exceeded the previous record set by Barack Obama, who granted 1,715 commutations. During his 2024 presidential run, Donald Trump said he would free Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht, who had received a life sentence for creating a website that connected drug buyers with drug sellers. “He’s already served 11 years,” Trump said. “We’re going to get him home.” Like Biden, Trump kept his promise, granting Ulbricht a “full and unconditional pardon” on the second day of his second term. Anyone who questions long prison sentences for nonviolent drug offenders should recognize these actions as appropriate uses of presidential clemency, aimed at mitigating injustices caused by draconian criminal laws. But Biden and Trump have also shown that presidents can abuse clemency in service of their personal interests. Biden did that on his way out the door, when he granted preemptive pardons to his relatives and allies. Trump did it hours later, when he approved blanket clemency for nearly 1,600 of his most enthusiastic supporters, all of whom had been charged with crimes related to the January 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol. I am not claiming that Biden and Trump exceeded their constitutional authority, which is very broad in this area. But they did undermine the rule of law by using that authority in ways that bear little resemblance to the situations that the framers seem to have had in mind when they granted it. The Constitution empowers the president to “grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.” That clause includes two explicit restrictions: Presidential clemency applies only to federal crimes, and it cannot be used to override congressional impeachments. The Supreme Court inferred a third limit in the 1866 case Ex parte Garland, saying the clemency power “extends to every offence known to the law, and may be exercised at any time after its commission,” which rules out pardons for future crimes. But with those three exceptions, the clemency power is usually described as “plenary,” meaning it is absolute and cannot be second-guessed by anyone else. Some legal scholars argue that further limits on clemency can be inferred from other parts of the Constitution, common law principles, or criminal statutes enacted by Congress. Those limits might, for example, preclude self-pardons or clemency in exchange for bribes. But even those arguable exceptions are not broad enough to encompass what Biden and Trump did. Still, it is fair to judge acts of clemency based on the original rationale for empowering presidents to block or mitigate criminal penalties. In 1788, Alexander Hamilton explained why “the benign prerogative of pardoning should be as little as possible fettered or embarrassed”: “The criminal code of every country partakes so much of necessary severity, that without an easy access to exceptions in favor of unfortunate guilt, justice would wear a countenance too sanguinary and cruel.” Why entrust this power to one official? “As the sense of responsibility is always strongest, in proportion as it is undivided,” Hamilton wrote, “it may be inferred that a single man would be most ready to attend to the force of those motives which might plead for a mitigation of the rigor of the law, and least apt to yield to considerations which were calculated to shelter a fit object of its vengeance.” Commutations for nonviolent drug offenders — a category of criminal unknown to Hamilton and his contemporaries — certainly seem like “mitigation of the rigor of the law” aimed at alleviating excessively “cruel” penalties. In Biden’s case, they also look like partial penance for his long record of supporting harsh drug laws. Trump slammed that record during his 2020 and 2024 campaigns, faulting Biden for championing legislation that had disproportionately hurt African Americans. Consistent with that critique, Trump commuted more than 60 drug sentences during his first term, starting with Alice Marie Johnson, a first-time offender who had received a life sentence for participating in a Memphis cocaine-trafficking operation. He highlighted Johnson’s case during his 2019 State of the Union address, in a 2020 Super Bowl ad, and at the 2020 Republican National Convention, where Johnson gave a grateful speech. “You have many people like Mrs. Johnson,” Trump told Fox News in 2018. “There are people in jail for really long terms.” The solution, he added, had to go beyond clemency. “There has to be a reform, because it’s very unfair right now,” he said. “It’s very unfair to African Americans. It’s very unfair to everybody.” True to his word, Trump supported the FIRST STEP Act, a package of criminal justice reforms that he signed into law at the end of 2018. Trump’s sincerity on this issue is open to question. He embraced sentencing reform based on the advice of his son-in-law Jared Kushner and later complained that he did not reap the political benefit he expected. And even as Trump decried “very unfair” drug penalties, he praised Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, who likened himself to Adolf Hitler while urging the murder of drug users. Trump also repeatedly recommended the death penalty for drug dealers. He had difficulty reconciling that contradiction, and his ambivalence may help explain why his commutation total (94) paled next to Obama’s or Biden’s — although it was still an improvement on Republican predecessors such as George W. Bush (11), George H.W. Bush (3), and Ronald Reagan (13). Biden and Trump showed they could use “the benign prerogative of pardoning” in a way that Hamilton might have approved. The same cannot be said of Biden’s clemency for members of his own family, which began with his December 1 pardon for his son. Hunter Biden had been convicted of federal tax and firearm felonies, and he was about to be sentenced for those crimes. His father had repeatedly said he would not intervene in those cases. But he reneged on his promise to respect the legal process, claiming Hunter was a victim of politically motivated prosecution. That charge was puzzling, since David Weiss, the special counsel who brought both cases, had been appointed by Biden’s own attorney general. Biden argued that Hunter had been “unfairly” and “selectively” prosecuted because he was the president’s son. Biden said it was “clear” that “Hunter was treated differently” from similarly situated defendants, adding that “the charges in his cases came about only after several of my political opponents in Congress instigated them to attack me and oppose my election.” A disinterested observer might surmise that Hunter was indeed “treated differently” because of his father’s position, but not in the way Biden meant. That does not necessarily mean Hunter was “a fit object of [the law’s] vengeance,” as Hamilton put it. The gun charges, at least, were based on conduct that never should have been criminalized to begin with. Under 18 USC 922(g)(3), it is a felony for “an unlawful user” of “any controlled substance” to receive or possess a firearm. Hunter, an admitted crack user, violated that law by purchasing a revolver from a Wilmington, Delaware, gun shop in 2018. He also violated two other laws, 18 USC 922(a)(6) and 18 USC 924(a)(1)(A), by falsely denying his drug use on the form that you have to complete when you buy a gun from a federally licensed dealer. Section 922(g)(3) is not limited to crack addicts. It also encompasses, for example, cannabis consumers (even if they live in a state where marijuana is legal) and anyone who takes a medication prescribed for another person, such as someone who uses a relative’s leftover Vicodin after suffering a back injury. Under that law, it does not matter whether a drug user handles guns while impaired or only when he is stone-cold sober. That policy, which is akin to a blanket ban on gun possession by anyone who drinks alcohol, makes little sense, and several federal courts have deemed prosecutions under Section 922(g)(3) inconsistent with the Second Amendment. When Hunter Biden tried that argument, the judge overseeing his case ruled that he would have to wait until after he was convicted. Hunter’s constitutional argument pitted him against his own father, who enthusiastically supports the law that his son violated. The Biden administration stubbornly defended Section 922(g)(3) against Second Amendment challenges by marijuana users. Biden even signed a law that increased the maximum sentence for his son’s crime from 10 to 15 years and created another potential charge, likewise punishable by up to 15 years in prison, for drug users who obtain guns. All told, someone who did what Hunter did could face combined maximum penalties of nearly half a century under current law. Biden seems to think a drug user who buys a gun is committing a grave crime that merits a stiff prison sentence — except when his son does it. It’s true that violations of Section 922(g)(3) are rarely prosecuted. Although survey data on drug use and gun ownership suggest that potential defendants number in the tens of millions, the Justice Department prosecuted an average of just 120 such cases a year from FY 2008 to FY 2017. But people who are unlucky enough to be caught can suffer severe punishment. In a case where a federal appeals court overturned a Section 922(g)(3) conviction, a gun-owning marijuana user was sentenced to nearly four years in prison. Biden also complained that Weiss threw the book at Hunter after a DOJ plea deal fell apart. Although Weiss initially brought a single charge that he was prepared to drop once Hunter had completed a diversion program, he added two more charges after Hunter insisted on going to trial, raising his potential sentence from 0 to 25 years. That sort of hefty “trial penalty,” which coerces defendants into surrendering their Sixth Amendment rights, is indeed troubling. But unfortunately, it is par for the course in a criminal justice system where nearly all convictions result from guilty pleas. Biden’s pardon for Hunter, in short, featured several shades of hypocrisy, which the president justified by claiming the charges were driven by politics — sounding very much like Trump, who claimed every civil and criminal case against him was invalid for similar reasons. And to guard against future charges against his son under the incoming Trump administration, Biden’s pardon not only spared Hunter sentencing on the gun and tax charges but also barred his prosecution for any federal crimes he might have committed from January 1, 2014, through December 1, 2024. Biden took the same sweeping approach and invoked the same excuse when he pardoned five other relatives on January 20. “My family has been subjected to unrelenting attacks and threats, motivated solely by a desire to hurt me — the worst kind of partisan politics,” he said. “Unfortunately, I have no reason to believe these attacks will end.” Biden had in mind Trump’s repeated threats to investigate “the entire Biden crime family” based on vague suspicions of corruption. As a result of Biden’s pardons, those allegations will never be fleshed out or tested by investigators, prosecutors, judges, or jurors. While Trump’s claims may be completely baseless, we will never know for sure, and the pardons carry an unavoidable implication of guilt. Biden granted similarly sweeping pardons to former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley, former Covid-19 adviser Anthony Fauci, and the members of the House select committee that investigated the Capitol riot. “I believe in the rule of law, and I am optimistic that the strength of our legal institutions will ultimately prevail over politics,” he said. “But these are exceptional circumstances, and I cannot in good conscience do nothing. Baseless and politically motivated investigations wreak havoc on the lives, safety, and financial security of targeted individuals and their families. Even when individuals have done nothing wrong — and in fact have done the right thing — and will ultimately be exonerated, the mere fact of being investigated or prosecuted can irreparably damage reputations and finances.” Milley, a vocal Trump critic who has described his former boss as “fascist to the core,” seems to fall into the category of potential targets who “have done nothing wrong” — or at least, nothing criminal. Trump said Milley deserved to be executed for calling his Chinese counterpart in 2020 and 2021 to assure him that rumors of an impending U.S. attack were baseless. Trump’s threats against the members of the January 6 committee likewise seem legally groundless. Fauci’s case is a closer call. Fauci “flat-out lied to Congress when he said that, no, the federal government had not funded gain-of-function research at the Wuhan Institute for Virology,” Sen. Ted Cruz (R–TX) said during a December 2022 interview on Fox News. Although the National Institutes of Health later “made clear that was a lie,” Cruz complained, Attorney General Merrick Garland “won't prosecute him.” In a July 2021 letter to Garland, Sen. Rand Paul (R–KY) suggested that Fauci had violated 18 USC 1001, which applies to someone who makes “any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation” regarding “any matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch.” Thanks to Biden’s pardon, we will never know if prosecutors could have proven that case beyond a reasonable doubt. Likewise for additional charges that Hunter Biden might have faced in connection with his income taxes or allegations of foreign lobbying. And while prosecuting legislators for doing their jobs would be plainly frivolous (and probably unconstitutional), a decent respect for “the strength of our legal institutions” would require making Trump put up or shut up. Instead, Biden issued pardons that could be interpreted as validation of Trump’s wild allegations. At least two members of the January 6 committee seemed to recognize as much. “I am guilty of nothing besides bringing the truth to the American people and, in the process, embarrassing Donald Trump,” former Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) said on CNN a couple of weeks before Biden’s pardons. But Kinzinger worried that “as soon as you take a pardon, it looks like you are guilty of something.” Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA), meanwhile, noted the dangerous precedent that pardons like the ones Biden ultimately granted would set: “I don’t want to see each president hereafter on their way out the door giving a broad category of pardons to members of their administration.” Sarah Isgur, an attorney who served as a Justice Department spokeswoman during Trump’s first term, expressed the same concerns when she explained why she did not want a pardon, even though she had been labeled a “deep state” conspirator against Trump. “If we broke the law, we should be charged and convicted,” Isgur wrote in The New York Times on December 12. “If we didn’t break the law, we should be willing to show that we trust the fairness of the justice system that so many of us have defended. And we shouldn’t give permission to future presidents to pardon political allies who may commit real crimes on their behalf.” If presidents get in the habit of preemptively pardoning their underlings, impeachment will be the only real remedy for executive-branch officials who commit crimes, and that option is available only when their abuses come to light soon enough to complete the process. Coupled with the Supreme Court’s broad understanding of presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for “official acts,” this is a recipe for impunity that belies Biden’s avowed commitment to the rule of law. Trump likewise abandoned his supposed principles when he indiscriminately pardoned defendants who had rioted in his name, outraged by his stolen-election fantasy. “If you committed violence on that day,” JD Vance, now the vice president, said on January 12, “obviously you shouldn’t be pardoned.” A week later, Trump drew no such distinction, pardoning Capitol rioters who had assaulted police officers along with people who had merely entered the building without permission. That was too much even for Trump’s reliable supporters at the Fraternal Order of Police, who were “deeply discouraged” by his pardons. The police union had repeatedly endorsed Trump, saying he “supports our law enforcement officers” and “has our backs.” Trump’s pardons contradicted that commitment, but they were consistent with his interest in minimizing the crimes of his supporters. Although he once called the riot “a heinous attack on the United States Capitol,” he has more recently portrayed it as a “day of love” featuring “heroes” and “patriots” who were unjustly punished for expressing their views. The pardons, Trump claimed, were necessary to correct “a grave national injustice” and begin “a process of national reconciliation.” But such a reconciliation is impossible when the president is willing to excuse political violence as long as it is perpetrated by his supporters. Hamilton thought “the benign prerogative of pardoning” would allow mercy in appropriate cases. With the notable exceptions of Obama and Biden, we have not seen much of that in recent decades, although perhaps their examples will encourage future presidents to be less stingy. Hamilton also thought that entrusting a single person with the power of clemency would “inspire scrupulousness and caution” and that “the dread of being accused of weakness or connivance” would foster “circumspection.” Biden and Trump managed to dash that already beleaguered hope in a single day.

Jacob Sullum, a senior editor at Reason magazine, is the author of Beyond Control: Drug Prohibition, Gun Regulation, and the Search for Sensible Alternatives, forthcoming from Prometheus Books.

|