|

In this issue: - AI's Impact on the Written Word is Vastly Overstated—LLMs are not the first time that the cost of producing text at a given quality level has dropped precipitously. Since we already live in a world where there's an effectively infinite amount of verbiage on any given topic, it won't be too big an adjustment to keep moving in that direction. In fact, it's a smaller media shift than the introduction of blogging and spellcheck.

- VC IPOs—Turning a craft business into mass production means having predictable enough cash flows that you can put a multiple on them.

- Sovereign Wealth Funds—What does it mean for the US to actually stock up on crypto?

- The Return of Structured Products—They're just a way to separate a financial institution's balance sheet from its operations.

- LLM Moderation—Nanny products don't scale.

- Risk Management—Knowing what a blowup looks like is a good skill for a risk manager.

AI's Impact on the Written Word is Vastly Overstated

If you've spent much time in online discussions of LLMs, you've probably encountered references to how we'll need the text equivalent of low-background steel. It's a fun analogy: ever since the development of nuclear weapons, metals have been contaminated with fallout, so for a while any piece of equipment that needed to be sensitive to radiation had to be constructed from pre-war steel. (Apparently not so big a problem any more as the level of background radiation has declined—more on this later.) The argument was that we'd have the same problem in text: the only way to really trust that something was written by a trustworthy human source rather than some algorithm guessing the next word based on statistical distributions. The cost of machine-produced text is orders of magnitude lower than the old-fashioned kind, and soon enough, we won't be able to trust anything we read.

I disagree. AI is a big deal in many fields, but for this particular issue—reducing the level of trust we have in the written word, and making it harder for all of us to have some sort of shared reality—it ranks well below the printing press, and probably closer to, and best compares to, blogs and spellcheck.

The printing press is actually a good example of why the impact of cheaper writing and distribution on the truth is ambiguous. The pre-printing press economics of publishing were dominated by the cost of laboriously hand-copying individual works. This had a few impacts:

- Raising the cost meant that the books that made sense to write were the ones with high, certain demand. That meant lots of religious texts, some classics of philosophy, the Canterbury Tales, etc. One of the most popular non-religious books of pre-printing press era—with perhaps as many of a thousand copies in print—was The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. This is a bit like Marco Polo's stories, with a heavy helping of plagiarized fiction.

- Raising this cost also meant that the marginal cost of making the books look nice was lower. If you're waiting six months for someone to finish your copy of the New Testament, does it really make a difference to wait seven months and see some more decorative flourishes in the text?

Newly-printed books had lower production values, because of that marginal cost argument. But there were many more of them, which made it more likely that a Mandeville reader would recognize sections cribbed from Pliny, or note that Marco Polo's descriptions of China sound a bit more plausible, albeit less fun. Scarcity of text encourages writers to spend more time figuring out what's really true, but it also means that compelling lies have less competition.

If you look at the media environment once printing was established, it actually feels quite familiar: Daniel Defoe of Robinson Crusoe fame was an avid political pamphleteer, including a piece suggesting the mass execution of religious dissenters in England execution (the scholarly consensus is that he's doing what, in modern parlance, we'd call a bit. Like many people on Twitter today, he posted it anonymously, got outed, and found himself in big trouble as a result.) He also wrote ghost stories, foreign policy tracts, opinionated pieces on the money supply, etc. He was, in other words, what you'd refer to as a "blogger" in the 2000s and a "Substacker" more recently: someone with few or no institutional affiliations, who publishes opinionated pieces on a wide range of subjects.

That type has existed in some way since the dawn of mass media, but its importance varies. There's a narrative that the US media environment started getting more fractured in the 1980s, and has continued in that direction to the present, but it's really tracking a cycle. The US media environment of the mid-twentieth century was surprisingly consolidated: there were only a few national papers of note, all of which were ostensibly focused on a specific location like New York, Washington, or Wall Street. (USA Today didn't launch until 1982); there were, famously, the big three TV networks; newspapers were increasingly monopolies ($, Diff); the cable TV buildout was early; and while AM radio's shift from music to talk was underway, the Fairness Doctrine still meant that there were inconvenient features of talk radio—a station with a hit conservative show needed an offsetting progressive one, and vice-versa, so it was hard for anyone to build a political brand that had any real appeal to just one group.

All of this was already changing before the Internet got big, but blogging was a qualitatively different change. In general, important decisions get made on the basis of one-on-one conversations, small group discussions, and the written word; very few important people get most of their ideas from TV or radio. That meant that in the pre-Internet ecosystem, people got daily printed news from a comparatively small set of sources, could read the long tail of ideas in books, and had something in between in magazines—a little less timely than newspapers, but feasibly a little longer than books. (The decline of the magazine has been invisible, but it's a big deal: Liar's Poker, The End of History and the Last Man, and the entire gonzo genre were all born in magazine form; both Vannevar Bush and Rachel Carson both influenced public policy through magazine pieces.

Blogs occupied a niche that was faster than a daily paper, less editorially controlled than newspapers or magazines, and with zero barriers to entry. It turned out that some of the old media had been coasting on high production values and not investing enough in the valuable complementary good of having an accurate mental model of the world and updating it according to new information. Blogging was a curiosity for a while. The New Yorker covered the phenomenon early, in a piece that treated it as a novelty: "[W]hen you find an article or a Web site that grabs you, you link to it—or, in weblog parlance, you "blog" it. Then other people who have blogs—they are known as bloggers—read your blog, and if they like it they blog your blog on their own blog." One of the subjects of the article did, of course, blog it, though this was so long ago that [when one of the subjects of the article inevitably blogged about it, he linked to NewYorker.com and told his readers the cover date and page range—why would you expect a magazine article to have a hyperlink?

What blogging meant was that people could participate in the discourse, in the medium that the most influential people prefer, without any vetting whatsoever. They could win by being first, if a story developed just after the paper hit the presses. They could indefinitely extend their own deadlines if the piece needed it. For a while, blogging coexisted with the media, free-riding a bit on reporting but getting stories more distribution. Bloggers mostly weren't flying off to exotic locations to provide on-the-ground coverage of coups and famines, but they were finding those stories and making them famous. When blogging started to get serious blowback from the mainstream media, it was for actually breaking news, albeit of the news-about-the-news variety: CBS ran a story about George W. Bush's national guard record, the linchpin of which was a memo, ostensibly written in 1973 by Bush's commanding officer, that turned out to be made in Microsoft Word. Since blogging is, intrinsically, an act of media analysis wrapped in media itself, this was the perfect story—there's a very reasonable case that George W. Bush did shirk his obligations (or, if not, that he was uncommonly patriotic for a rich kid with an influential dad and no discernable interests other than partying). But CBS had messed up, and bloggers were able to respond to their defenses faster than they could come up with new ones. The blogosphere claimed a scalp in the form of Dan Rather's resignation from CBS, but they also got a memorable pejorative from the CEO of CNN: "It's an important moment, because you couldn't have a starker contrast between the multiple layers of checks and balances, and a guy sitting in his living room in his pajamas writing what he thinks." It was a big change for a story to be driven almost entirely by independent media: I. F. Stone, an independent newsletter writer, was the first journalist to point out that the Gulf of Tonkin incident didn't particularly add up, but this didn't have an impact until the story was picked up by mainstream outlets.

Pajama-clad or not, bloggers stuck around, and they forced other news organizations to adapt to their norms. Now, it's common for stories to be posted quickly and then repeatedly edited; traffic gets measured and talked about even if it's not a journalist's only performance indicator; major media companies make fewer pretensions to partisanship as a result of competing against independent writers who made no attempt whatsoever to disguise their biases; and blogging melded with the establishment so seamlessly that there are writers today who broke into the lucrative and important business of mainstream media by blogging (e.g. Matt Yglesias) and bloggers who used their mainstream media fame to break into the lucrative business of independent publishing (e.g. Matt Yglesias). In retrospect, the logistics of printing a couple million copies of the same set of text and delivering it by truck should not have determined the entire structure of the prestige news business, but they did, until they didn't.

Whether we like it or not, we live in a post-blogging world. But there are smaller-scale ways that textual technology has had a big impact, like spellcheck. Before spellcheck existed, one trivial heuristic for deciding what online posts to ignore or not was to ask a few simple questions, like: does this person know the difference between "there" and "they're"? Do they end interrogative sentences with question marks? Are they, in short, basically literate? In one-on-one communications, this heuristic breaks down, because the best way to tell how high someone is in a corporate hierarchy is how often they use constructions like "thx," but in a one-to-many environment, proper spelling and grammar was proof-of-work: either this person not only wrote a first draft, but literally went through the heroic process of rereading it to see if they'd made any mistakes, or this person is so textual, both in terms of their input and their output, that they naturally produce basically perfect first drafts. Either way, it was an easy-to-spot signal that made triaging writing by unfamiliar people easier.

Tools like Grammarly take this a bit further, and at this point LLMs make it so that everyone who wants to can write whatever email they need to in whatever tone they want (yes, you can use ChatGPT to Chad up your work emails by removing all of the apologies and clarifications). This can move writing a little closer to 90th percentile, when it's being used by someone who could produce the same result if they were a bit more diligent. But it can also elevate basically any coherent thought into a message that reads like it was produced by a college-educated professional.

Eliminating the ability to judge people based on how well they write is a social shift that, at least for the Extremely Online, is an act of linguistic egalitarianism on par with the abolition of the thou/you distinction. It's a huge deal if you can't quickly and superficially judge a text based on those signifiers, and instead have to engage with the ideas before dismissing them as worthless.

To handle this, we end up using some combination of algorithmic feeds and opt-in subscriptions. There is far more content being written online than anyone can consume, even if they narrow the scope to their interests. And this is why generative AI won't be that big a deal for text: there's already an effectively unlimited supply of people who are writing completely deranged things but can present them with the same design standards and theoretical distribution as a major media outlet (blogging! Substack!) and the same text-level production values, too (spellcheck!). We already implicitly opt out of the overwhelming majority of what we could read. And whether we read .01% or .001% of what theoretically interests us doesn't make much of a practical difference. After all, we can only consciously process 10 bits of information per second, which amounts to ~2gb in an average lifetime, so we have to opt in wisely.

Diff JobsCompanies in the Diff network are actively looking for talent. See a sampling of current open roles below: - A Google Ventures-backed startup founded by SpaceX engineers that’s building data infrastructure and tooling for hardware companies is looking for full-stack and front-end focused software engineers with 3+ years experience, ideally with data intensive products. (LA, Hybrid)

- A company building better analytics for pricing insurance is looking for a senior software engineer who likes turning messy data into clear answers. (NYC or Boston)

- An OpenAI backed startup that’s applying advanced reasoning techniques to reinvent investment analysis from first principles and build the IDE for financial research is looking for a data engineer with experience building robust data infrastructure and performant ETL pipelines that support intense analytical workloads. (NYC)

- A company building the new pension of the 21st century and enabling universal basic capital is looking for a mobile-focused engineer who has experience building wonderful iOS experiences. (NYC)

- An AI startup building regulatory agents to help automate compliance for companies in highly regulated industries is looking for lawyers with 3+ years of big law experience to help improve their product and core models. Crypto experience / familiarity a plus. (NYC)

Even if you don't see an exact match for your skills and interests right now, we're happy to talk early so we can let you know if a good opportunity comes up. If you’re at a company that's looking for talent, we should talk! Diff Jobs works with companies across fintech, hard tech, consumer software, enterprise software, and other areas—any company where finding unusually effective people is a top priority. Elsewhere

VC IPOs

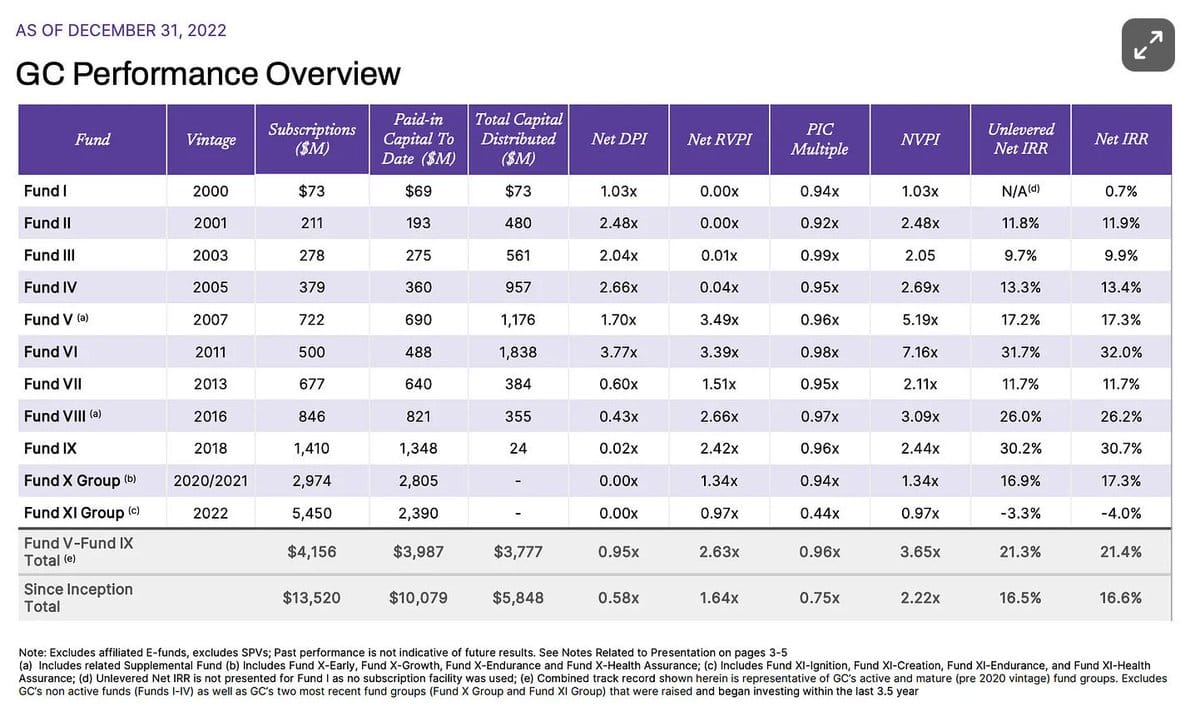

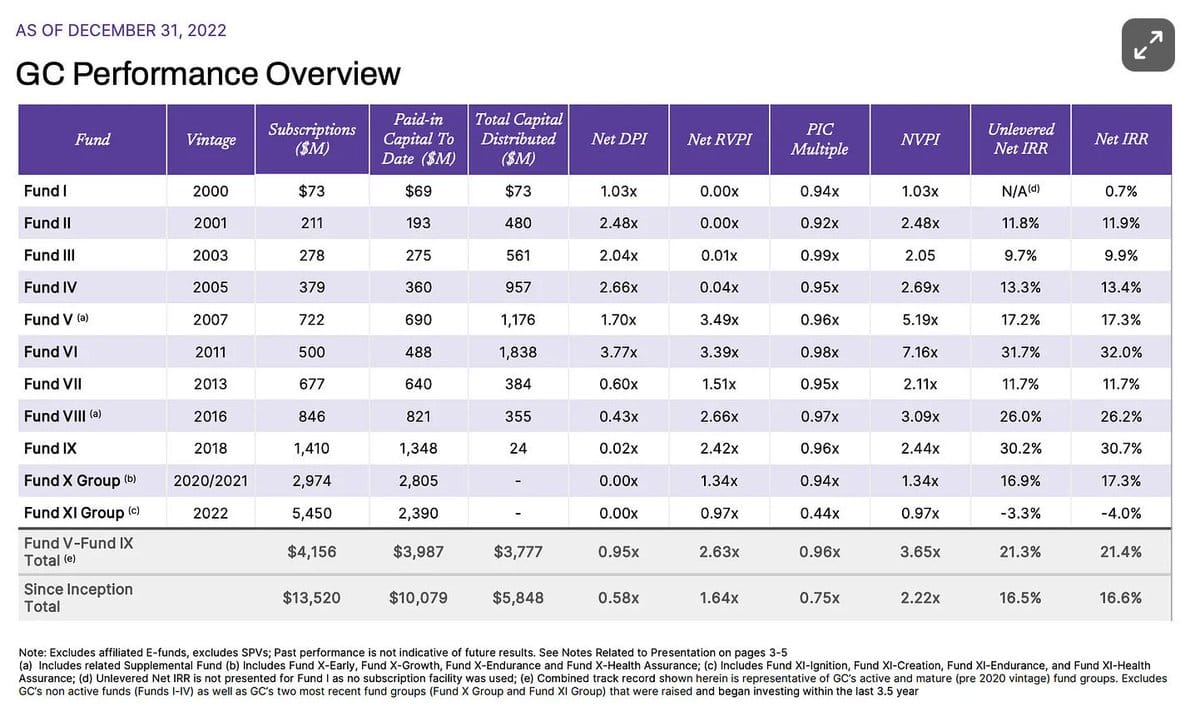

Managing other people's money is, in some respects, a fantastic business. There are minimal capital requirements by default, the mix of recurring and performance-based fees means it's possible to allocate slices of the capital structure to employees of varying risk tolerance, and high-profile firms have access to both money and deals, which keeps them high-profile. On the other hand, it's a business with the automatic headwind that indexing offers roughly zero fees for performance that is, depending on the investor and the benchmark, pretty similar. Over time, asset managers have had to build something that looks more like a traditional operating business, with fixed costs, long-term investments, strategic ventures that burn cash for a while before they turn a profit (or fail), etc. And when a company's economics start to approach those of the median American industry, but its cachet remains, there's a temptation to IPO. So General Catalyst aims to do exactly that. GC still has a great track record, and it's not as if they're trying to foist a subpar asset on public markets. The general shape of the industry is moving away from small-scale and capital-light, and towards something whose returns on capital look a bit more normal.

(Via Aidan Gold on Twitter.)

One feature of the financial business is that firms start out very personal—there are plenty of hedge funds and venture firms named after their partners, whereas it's a little weird to encounter "Huang & Co., purveyors of fine GPUS since 1993" and the like. But investors can't help but think about terminal multiples and comps, and what price they'd put on the cash flows generated by one specific person. What they often conclude is that the real money is in building an institution, not a firm defined by one person or by a founding team. It's a big accomplishment to build one, but it also means letting go.

(Incidentally, law firms seem particularly attached to the idea that there can be no more prestigious job than to work at a firm whose name consists entirely of a list of dead people. It's actually an interesting perk; I don't know who the best doctor or dentist in the 1960s was, but I have to assume that Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher, and Flom—the people, not the firm—were all pretty good.)

Sovereign Wealth Funds

Apparently, the US really is doing a crypto sovereign wealth fund, which was clarified in the most volatility maximizing way—first, by listing a bunch of less-known cryptocurrencies that would be in it ("XRP, SOL, and ADA,") and then adding an hour later that Bitcoin and Ethereum would also be included. There is not a strong argument that the US should have such a fund ($, Diff), and one of the reasons that post didn't talk about is that it entails choosing assets. It's hard for the government not to tacitly endorse a token by including it in the fund, and once that happens it gets harder for the token or its promoters to be subject to much regulatory pressure. So the US would effectively be splitting crypto into two categories, one of which has the US's blessing (but the overhang of a sovereign fund being rapidly liquidated in January 2029, whether by a hypothetical President Vance or whoever the Democrats nominate), and one of which didn't. Unfortunately, the bigger the institution betting on a decentralized software product, the more they de facto centralize it in the bargain.

This is also a good example of the Trump Straddle, i.e. the phenomenon that Trump tends to treat the market as an indicator of whether or not he has permission to pursue particular policies. When stocks are high, he'll take it personally and do extra-Trump things that the market doesn't like (tariffs, immigration crackdowns, threatening to annex various places), and when the market drops, he does things that push it back up (canceling the above policies, sometimes tax cuts). This apparently works for asset classes other than equities; crypto rallied in response to Trump's victory in November, but the Coindesk 20 index solf off by over 30% post-inauguration on the grounds that he didn't do anything especially pro-crypto. All this noise was good for at least one crypto speculator, who made a well-timed and highly-levered bet ahead of the announcement, but cashed out before peak gains.

The Return of Structured Products

Structured products get a bad rap, even though all they really do is separate the two functions of financial companies: the operating business of finding a cheap way to raise capital and a scalable way to deploy it without resorting to capital markets, and then holding the resulting balance sheet. They're a way to essentially assemble the asset side of a bank from a collection of bundled loans in different categories; a mix of mortgages, auto loans, credit card debt, and loans to companies can all be assembled through structured products without the messy business of actually making those loans. So, in a way, it's a good sign that the industry is booming again, with record attendance at conferences ($, WSJ). Inevitably, some of this will end in tears ("A panel on data centers was so popular, attendees sat on the floor," is one of those lines that's very likely to be trotted out in grim retrospectives at some point.") But the general idea of separating what assets lenders own from how they make their loans is what finance is all about.

LLM Moderation

A few months ago, most of the big AI labs had converged on a norm where they'd release increasingly powerful models but have a growing range of restrictions on what those models could produce. Some of this was legally prudent; a company with billions in funding, or a subsidiary of a company with tens of billions in profits, is a tempting target for a lawsuit, so there's a high ROI on making sure that when the model is asked to produce a cartoon mouse, it does something original or faithfully reproduces Steamboat Willy rather than infringing on one of Disney's multi-billion dollar properties. But the models were also cautious about offending hypothetical users by saying or showing something inappropriate, which in turn offended actual users who found themselves in a Good Will Hunting-style battle to get the model to live up to its own potential. An internal memo at Google shows that Sergey Brin doesn't like that, and doesn't want "nanny products." This, too, is just a prudent business decision: as the models get more powerful, it gets harder to find every edge case where they can be persuaded to ignore their rules, and the rules themselves lead to more annoying edge cases where even the people in charge can't predict what the models will or will not allow ($, Diff).

Risk Management

One of the fastest-growing multi-manager funds is Verition, whose founder previously oversaw one of the fastest-shrinking multi-manager funds, Amaranth, when it lost 60% of its investors' capital in a week ($, WSJ). The Amaranth-to-Verition story highlights how this particular fund strategy has evolved over time: its initial pitch was about diversified sources of upside, where running as many strategies as possible maximized the odds of having some capital deployed in whatever that year's winning trades were. As both LPs and prime brokers have gotten more sophisticated, the right variable to focus on has shifted to downside risk. And who could have a more visceral, intuitive understanding of that than someone who was on the wrong side of it in a spectacular way?

|