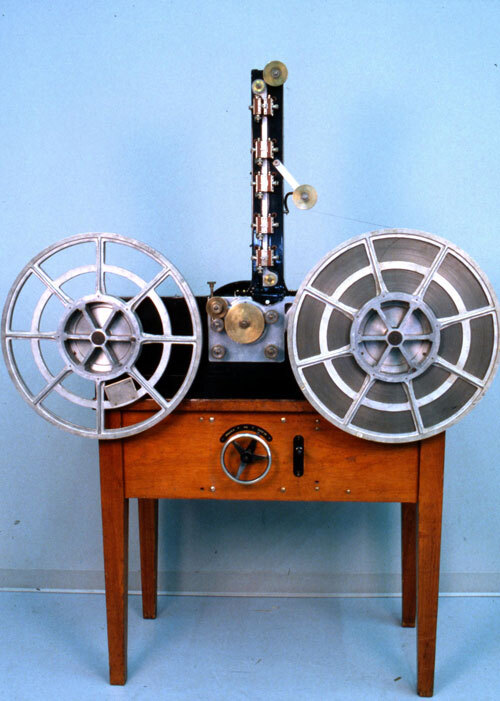

A Blattnerphone owned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. (Canada Science and Technology Museum/Flickr)

Steel wheel: One of the first magnetic tape formats used literal steel as a recording medium

In many ways, most magnetic tape is something of a symphony of metal and plastic, with magnetic materials on the tape interacting with a tape head, which amplifies the materials into sounds.

That symphony, which I wrote about last fall, largely emerged after World War II—an invention that emerged from Nazi Germany that was perfected by the United States.

But it wasn’t the first magnetic recording format. For decades, the concept of recordable magnetized wire, first developed by Danish telephone engineer Valdemar Poulsen as the telegraphone, was something of an indirect competitor to the more common mechanical recording devices of the time, in part because there was no simple way to amplify the sound that the early device created. The resulting noise was loud enough that it could be head over headphones or replayed over a telephone wire, however.

At the 1900 Paris World Exhibition, Poulsen recorded the voice of a world leader, Emperor Franz Josef, on magnetic wire—which is likely the oldest surviving magnetic recording in world history.

The basis of Poulsen’s formats would eventually evolve into magnetic tape thanks to a series of inventors who further improved on his basic ideas. One such figure, German engineer Dr. Curt Stille, took advantage of the expiration of Poulsen’s patents to further develop the technology, which would eventually benefit from the invention of vacuum tube amplifiers. Stille’s work, per Old BBC Radio Broadcasting Equipment and Memories, was good enough for voice dictation, but not for, say, playing on the radio.

In a 1983 article for Cinema Journal, writer William Lafferty explained that market realities—particularly, the fact that it was more cost-effective to hire a stenographer than to record on wire in the 1920s—forced Stille to change that. He developed the wire concept into a flattened steel tape, which was around 6mm wide, half a millimeter thick, and held into place with sprocketed holes to ensure synchronization. The target audience for this technology was the cinema, where demand for “talkies” necessitated a focus on audio quality.

Accordingly, Stille’s work attracted the interest of a onetime cinema owner and budding entertainment industry impresario named Ludwig Blattner, who expanded on Stille’s ideas and further developed them, eventually giving them his name—the rolls-off-the-tongue term that is the Blattnerphone. Blattner, a German-born UK resident who was in the most of launching film studio, came to the technology after having a falling out with the manufacturer of a disc-based sound-on-film system.

It was a complex system, having to keep pace with the film that was playing despite the fact that the recording on steel had to travel 60 percent faster than the film did.

Blattner had tried to launch a studio with experimental proprietary technologies—his studio also licensed out the Keller-Dorian color cinematography technique, developed in France in the 1920s—but the technologies failed to gain marketshare in the film industry. As Lafferty noted, contemporary takes on the Blattnerphone were not kind:

The Blattner demonstration of his system of electromagnetic sound re-cording on wire has created surprisingly little stir … The demonstration came in for quite a lot of criticism, without any imaginative appreciation of the latent possibilities of the system. It must have been rather disheartening for Blattner.

It didn’t help that the technology had a number of technical flaws. As you might guess, replicating audio from a giant machine is likely to be tough, the film synchronization process complex, and the steel tape was only manufactured by a handful of companies.

On top of that, if there was an error in the audio, fixing it required spot welding (and the spots where the steel was welded were noticeable), and because we’re talking about magnetically charged steel here, obviously it’s going to face issues if there are magnets nearby. And given the fast playback speeds, if something breaks, it likely means that a sharp piece of metal is going to whip across the room, causing safety issues.

A later model of Blattnerphone. (via Old BBC Radio Broadcasting Equipment and Memories)

However, all was not lost for the strands of steel tape. The Blattnerphone was simply focused on the wrong industry. In the 1930s, major radio producers such as the BBC were looking for ways to record audio basically in real time, so that they could record without delay. The Blattnerphone, for all its gigantic faults, offered that.

Per Old BBC Radio Broadcasting Equipment and Memories, the broadcaster paid £500 for access to the first machine, plus £1,000 per year after that and £250 for each additional machine. With inflation considered as well as conversion rates, that’s tens of thousands of U.S. dollars, each, for recording devices that were effectively obsolete a decade later.

It was not a perfect solution, mostly a good enough one, explains the site’s Roger Beckwith, with the solution not considered good enough for music, just spoken word, due to issues with tape speed inconsistency. Ultimately, it was not heavily used in BBC productions.

“At the end of 1932 a programme called ‘Pieces of Tape’ was produced in the Blattnerphone room, being a compilation of several tapes recorded that year,” he wrote. “However, the mechanics of the editing process were too laborious for regular productions using the technique.”

By 1935, the machines had been replaced with a new Blattnerphone made by the firm Marconi-Stille, which solved many of the inconsistency problems. While smaller than the initial machines, they still fairly huge, though, roughly the size of a washer and dryer combined—and kind of looking like one.

These machines are incredibly rare, and have barely, if ever, seen the light of day since the 1930. However, in 1992, one of the devices emerged on Australian television due in part to a requirement by the Canadian Broadcast Corporation to play their Blattnerphone devices. So the giant reels were sent to Australia, where a player was still located. You can see the surreal results above.

Lafferty noted that the innovation of the Blattnerphone highlighted how innovation from the film industry was something of a two-way street.

“The technology of practical sound motion pictures may have arisen out of the international radio and telephone companies, but the case of the Ludwig Blattner Picture Corp. Ltd. shows that, in turn, the international communications industry found within the fledgling sound film industry an innovative technology to exploit,” he said.