|

|

Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of the daily online journal Brain Pickings by Maria Popova. If you missed last week's edition — a young poet's love letter to our broken, beautiful world; Eleanor Roosevelt's reading of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights set to music, Coleridge on the sublimity of storms — you can catch up right here. And if you find any value and joy in my labor of love, please consider supporting it with a donation – I spend innumerable hours and tremendous resources on it each week, as I have been for fourteen years, and every little bit of support helps enormously. If you already donate: THANK YOU.

Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of the daily online journal Brain Pickings by Maria Popova. If you missed last week's edition — a young poet's love letter to our broken, beautiful world; Eleanor Roosevelt's reading of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights set to music, Coleridge on the sublimity of storms — you can catch up right here. And if you find any value and joy in my labor of love, please consider supporting it with a donation – I spend innumerable hours and tremendous resources on it each week, as I have been for fourteen years, and every little bit of support helps enormously. If you already donate: THANK YOU.

|

Who can weigh the ballast of another’s woe, or another’s love? We live — with our woes and our loves, with our tremendous capacity for beauty and our tremendous capacity for suffering — counterbalancing the weight of existence with the irrepressible force of living. The question, always, is what feeds the force and hulls the ballast.

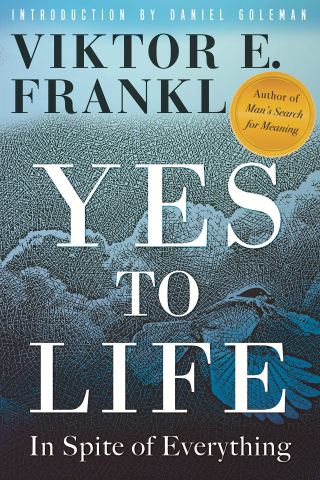

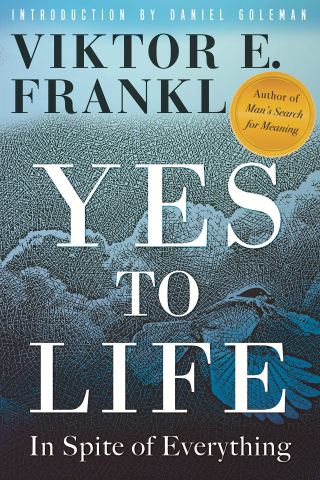

Viktor Frankl (March 26, 1905–September 2, 1997), having lost his mother, his father, and his brother to our civilization’s most colossal moral failure yet, having barely survived himself, Frankl takes up the question of what makes life not only survivable but worthy of living in what now lives as Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything (public library) — a slim, powerful set of lectures he delivered a mere eleven months after the Holocaust, just as he was completing the manuscript of the classic Man’s Search for Meaning.

Art from Trees at Night by Art Young, 1926. (Available as a print.)

Tucked into Frankl’s immensely insightful meditations on moving beyond optimism and pessimism to find the deepest source of meaning is a passage of great subtlety and great splendor — a portal to a truth so elemental that it might appear trite if stated merely as an abstract truism, but one which rises titanic and majestic from the crucible of this human being’s unfathomable lived experience.

In a sublime sidewise testament to the singular power of music, which some of humanity’s vastest minds have so memorably extolled, Frankl writes:

It is not only through our actions that we can give life meaning — insofar as we can answer life’s specific questions responsibly — we can fulfill the demands of existence not only as active agents but also as loving human beings: in our loving dedication to the beautiful, the great, the good. Should I perhaps try to explain for you with some hackneyed phrase how and why experiencing beauty can make life meaningful? I prefer to confine myself to the following thought experiment: imagine that you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favorite symphony, and your favorite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine; and now imagine that it would be possible (something that is psychologically so impossible) for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would agree with me if I declared that in this case you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like: “It would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!” It is not only through our actions that we can give life meaning — insofar as we can answer life’s specific questions responsibly — we can fulfill the demands of existence not only as active agents but also as loving human beings: in our loving dedication to the beautiful, the great, the good. Should I perhaps try to explain for you with some hackneyed phrase how and why experiencing beauty can make life meaningful? I prefer to confine myself to the following thought experiment: imagine that you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favorite symphony, and your favorite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine; and now imagine that it would be possible (something that is psychologically so impossible) for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would agree with me if I declared that in this case you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like: “It would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!”

Viktor Frankl

More than a century after Mary Shelley celebrated nature as a lifeline to sanity in considering what makes life worth living in a world savaged by a deadly pandemic, and decades before Tennessee Williams reflected as he approached his own death that “we live in a perpetually burning building, and what we must save from it, all the time, is love… love for each other and the love that we pour into the art we feel compelled to share: being a parent; being a writer; being a painter; being a friend,” Frankl adds:

Those who experience, not the arts, but nature, may have a similar response, and also those who experience another human being. Do we not know the feeling that overtakes us when we are in the presence of a particular person and, roughly translates as, The fact that this person exists in the world at all, this alone makes this world, and a life in it, meaningful. Those who experience, not the arts, but nature, may have a similar response, and also those who experience another human being. Do we not know the feeling that overtakes us when we are in the presence of a particular person and, roughly translates as, The fact that this person exists in the world at all, this alone makes this world, and a life in it, meaningful.

Art from Trees at Night by Art Young, 1926. (Available as a print.)

In how we suffer and how we love, Frankl concludes, is the measure of who and what we are:

How human beings deal with the limitation of their possibilities regarding how it affects their actions and their ability to love, how they behave under these restrictions — the way in which they accept their suffering under such restrictions — in all of this they still remain capable of fulfilling human values. How human beings deal with the limitation of their possibilities regarding how it affects their actions and their ability to love, how they behave under these restrictions — the way in which they accept their suffering under such restrictions — in all of this they still remain capable of fulfilling human values.

So, how we deal with difficulties truly shows who we are.

Yes to Life is a slender, spectacular read in its totality. Complement this fragment with Borges on turning trauma misfortune, and humiliation into raw material for art and Whitman, shortly after his paralytic stroke, on what makes life worth living, then revisit Frankl on humor as a lifeline to survival.

donating=lovingEvery week for fourteen years, I have been pouring tremendous time, thought, love, and resources into Brain Pickings, which remains free and is made possible by patronage. If you find any joy and solace in my labor of love, please consider supporting it with a donation. And if you already donate, from the bottom of my heart: THANK YOU. (If you've had a change of heart or circumstance and wish to rescind your support, you can do so at this link.)

monthly donation

You can become a Sustaining Patron with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a Brooklyn lunch.

|

|

one-time donation

Or you can become a Spontaneous Supporter with a one-time donation in any amount.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Partial to Bitcoin? You can beam some bit-love my way: 197usDS6AsL9wDKxtGM6xaWjmR5ejgqem7

|

|

“How can we use each other’s differences in our common battles for a livable future?” Audre Lorde asked while traveling in a divided world a generation after the landmark Universal Declaration of Human Rights declared that “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.” Another generation earlier — an interval imperceptible on the timescales of our evolutionary history — these rights were reserved for only one class of human family members: white men.

That a civilization was able to broaden the legal aperture of civic agency and human dignity so dramatically in so short a time was the triumph of two parallel and consanguine movements: women’s suffrage and abolition, propelled by a small, unrelenting tribe of pioneers in the middle of the nineteenth century. The most active and ardent of them were women — women like Susan B. Anthony and Julia Ward Howe, who spoke and wrote and rallied unrelentingly for human rights and civic agency; women like astronomer and abolitionist Maria Mitchell, who swung open the gates to women’s education in science and whose lovely lifelong friendship with Frederick Douglass was an honor to both; women who, in the aftermath of the Civil War, diverted their suffrage efforts from securing the vote for themselves to securing the vote for African Americans — parallel efforts for which Margaret Fuller had furnished the catalytic spark with her insistence that “while any one is base, none can be entirely free and noble.” (In a disquieting recompense for these women’s efforts, the right to vote was extended to black men half a century before it was extended to women of any ethnicity.)

In the city of Rochester in upstate New York there stands — or, rather, sits — a bronze sculpture depicting two of these courageous champions of freedom having tea: Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) and Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906), whose neighboring braveries blossomed into a real friendship after both moved to Rochester around the same time in their late twenties. It was in Rochester that Anthony voted in a presidential election, well aware she was going to be arrested for it; it was in Rochester that Douglass launched his epoch-making abolitionist newspaper (which he titled the North Star, in homage to the central role of astronomy in the Underground Railroad).

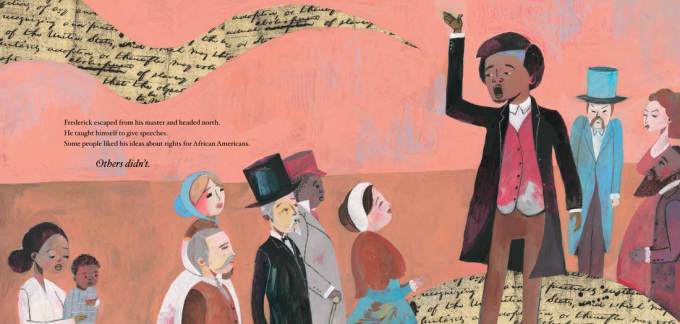

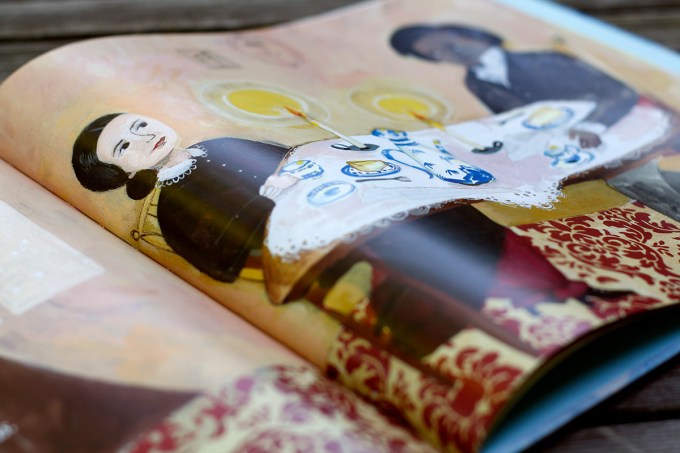

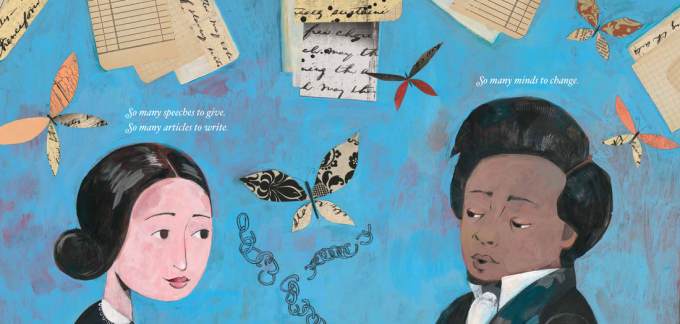

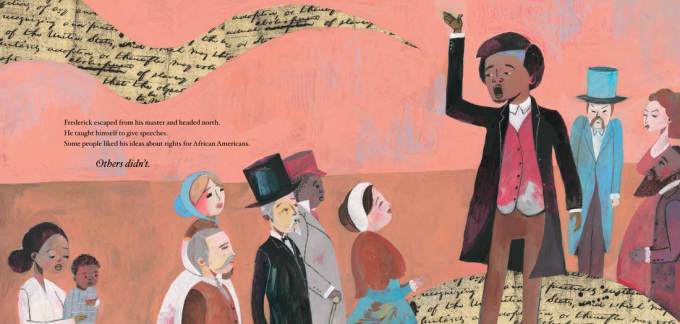

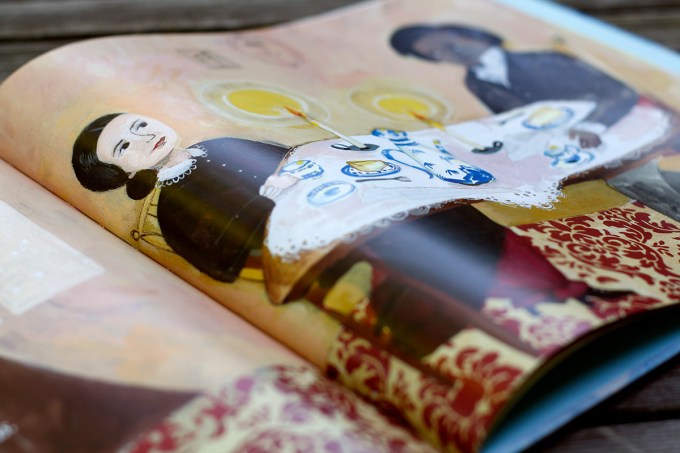

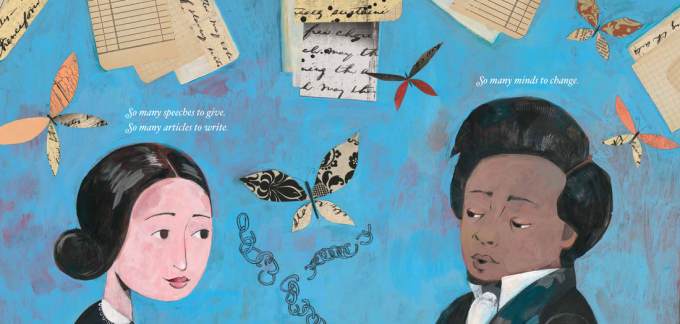

Inspired by the sculpture and the beautiful camaraderie behind it, Two Friends: Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass (public library) by Dean Robbins, illustrated by Selina Alko and Sean Qualls, tells the story of these two pioneering lives entwined in friendship through an imaginary evening of tea and cake.

We see each of them transcend the givens of their condition: Susan, excluded from formal education on account of her gender, educates herself in the founding ideals of her country and is galled by the hypocrisy of proclaiming the rights to live free and to vote, but denying those rights to more than half; Frederick, enslaved, teaches himself to read and write, then learns about the same ideals and is galled by the same hypocrisy of exclusion.

We see Frederick clad in his “gentleman’s jacket, vest, and tie,” and Susan in “a kind of pants called ‘bloomers,'” which she prefers over the cumbersome skirts that make it “hard to get things done.”

Both of them teach themselves to give speeches on justice and equality, both of them deliver those speeches before audiences to the applause of some and the vocal dismay of others, until the two eventually meet in Rochester and promise “to help each other, so one day all people could have rights.”

And so they do: We see them discuss their ideas and their plans over tea and cake and warm conspiratorial smiles.

So many speeches to give. So many speeches to give.

So many articles to write.

So many minds to change.

Couple Two Friends with a wondrous celebration of the rebels who won women political power, illustrated by the incomparable Maira Kalman, then savor other picture-book biographies of cultural heroes, pioneers, and visionaries: John Lewis, Keith Haring, Wangari Maathai, Maria Mitchell, Ada Lovelace, Louise Bourgeois, E.E. Cummings, Jane Goodall, Jane Jacobs, Frida Kahlo, Louis Braille, Pablo Neruda, Albert Einstein, Muddy Waters, and Nellie Bly.

Patti Smith listed among her criteria for a literary masterpiece that it must leave one so enchanted as to feel “immediately obliged to reread it.” Susan Sontag considered rereading an act of rebirth. I attest to this readily with my habit of rereading The Little Prince once a year every year, each time finding in it new revelations of meaning, new existential salve for whatever is ailing my life at that particular moment. We reread beloved books because on some level we recognize the temporality of all experience and the temporariness of the confluence of states and circumstances comprising the self at any given moment — we recognize that next year’s self will outgrow last year’s self and move on to a whole new set of challenges, hopes, and priorities, becoming, in some essential sense, a whole new self.

Virginia Woolf (January 25, 1882–March 28, 1941) was only twenty-one when she recorded this recognition with uncommon lucidity of mind and luminosity of language.

Virginia Woolf

In the summer of 1903, Woolf took two months’ respite from London’s bustle in the blue-green spaciousness of the English countryside, enjoying “a very free out of door life” and reading voraciously. “I read more during these 8 weeks in the country than in six London months perhaps.” Under the twin luxuries of time for reading and space for reflection, she arrived at a revelatory new understanding of why it is we read at all — what books do for the human spirit, how they furnish what Iris Murdoch would call “an occasion for unselfing,” and how they can perform the astonishing acrobatics of arising from one consciousness and reaching another — thousands, millions of others, across time and space — on such an intimate level, and in the process interleaving those myriad different consciousnesses into a shared wilderness of experience.

On the first of July, she writes in her diary:

I read a great deal… Besides this I write… But the books are the things that I enjoy — on the whole — most. I feel sometimes for hours together as though the physical stuff of my brain were expanding, larger & larger, throbbing quicker & quicker with new blood — & there is no more delicious sensation than this. I read some history: it is suddenly all alive, branching forwards & backwards & connected with every kind of thing that seemed entirely remote before. I seem to feel Napoleons influence on our quiet evening in the garden for instance — I think I see for a moment how our minds are all threaded together — how any live mind today is of the very same stuff as Plato’s & Euripides. It is only a continuation & development of the same thing. It is this common mind that binds the whole world together; & all the world is mind. I read a great deal… Besides this I write… But the books are the things that I enjoy — on the whole — most. I feel sometimes for hours together as though the physical stuff of my brain were expanding, larger & larger, throbbing quicker & quicker with new blood — & there is no more delicious sensation than this. I read some history: it is suddenly all alive, branching forwards & backwards & connected with every kind of thing that seemed entirely remote before. I seem to feel Napoleons influence on our quiet evening in the garden for instance — I think I see for a moment how our minds are all threaded together — how any live mind today is of the very same stuff as Plato’s & Euripides. It is only a continuation & development of the same thing. It is this common mind that binds the whole world together; & all the world is mind.

Art by Lia Halloran from A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader. Available as a print.

Later in life, Woolf would return to this realization in her exquisite account of the epiphany in which she understood what it means to be an artist, writing:

Behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern… the whole world is a work of art… there is no Shakespeare… no Beethoven… no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself. Behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern… the whole world is a work of art… there is no Shakespeare… no Beethoven… no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself.

And yet, even at twenty-one, she understood how momentary these glimpses of elemental truth are — how easily this sense of inter-belonging, this thing-itselfness of being, slips out of our grasp. She continues the same 1903 diary entry with the swift pivot — as swift as the mind’s — from this awareness that “all the world is mind” to the habitual loss of perspective as the cotton wool drops over our eyes and unworlds us once more:

Then I read a poem say — & the same thing is repeated. I feel as though I had grasped the central meaning of the world, & all these poets & historians & philosophers were only following out paths branching from that centre in which I stand. And then — some speck of dust gets into my machine I suppose, & the whole thing goes wrong again. Then I read a poem say — & the same thing is repeated. I feel as though I had grasped the central meaning of the world, & all these poets & historians & philosophers were only following out paths branching from that centre in which I stand. And then — some speck of dust gets into my machine I suppose, & the whole thing goes wrong again.

Art by Shaun Tan from A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader. Available as a print.

More than a decade later, Woolf refined the sentiment in one of the extraordinary essays she composed during her quarter century as a critic for the Times Literary Supplement, newly collected in Genius and Ink: Virginia Woolf on How to Read (public library) — a book which, had I not been too consumed by rereading beloved books of yore to realize its publication, I would have ardently included among my favorite books of 2019.

Like the Nobel-winning Polish poet Wisława Szymborska, whose contemplative criticism uses books less as specimens for review than as springboards for soaring meditations on life and art, Woolf treats each book she reviews as a stone dropped from the coat-pocket into the Ouse of life, observing first its essential stoneness of form and then the widening circles of understanding rippling into the river of consciousness. Into the first essay from the collection, writing about Charlotte Brontë’s novels, Woolf nestles this exquisite insight into what makes a great work of art — the kind to which we keep returning again and again:

There is one peculiarity which real works of art possess in common. At each fresh reading one notices some change in them, as if the sap of life ran in their leaves, and with skies and plants they had the power to alter their shape and colour from season to season. To write down one’s impressions of Hamlet as one reads it year after year, would be virtually to record one’s own autobiography, for as we know more of life, so Shakespeare comments upon what we know. There is one peculiarity which real works of art possess in common. At each fresh reading one notices some change in them, as if the sap of life ran in their leaves, and with skies and plants they had the power to alter their shape and colour from season to season. To write down one’s impressions of Hamlet as one reads it year after year, would be virtually to record one’s own autobiography, for as we know more of life, so Shakespeare comments upon what we know.

Complement with Rebecca Solnit on why we read, André Gide on the five elements of a great work of art, and the young poet May Sarton’s arresting account of meeting Woolf, then revisit Woolf’s own arresting account of a total solar eclipse and her abiding insight into illness, love, gender, writing and self-doubt, and the relationship between loneliness and creativity.

donating=lovingEvery week for fourteen years, I have been pouring tremendous time, thought, love, and resources into Brain Pickings, which remains free and is made possible by patronage. If you find any joy and solace in my labor of love, please consider supporting it with a donation. And if you already donate, from the bottom of my heart: THANK YOU. (If you've had a change of heart or circumstance and wish to rescind your support, you can do so at this link.)

monthly donation

You can become a Sustaining Patron with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a Brooklyn lunch.

|

|

one-time donation

Or you can become a Spontaneous Supporter with a one-time donation in any amount.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Partial to Bitcoin? You can beam some bit-love my way: 197usDS6AsL9wDKxtGM6xaWjmR5ejgqem7

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of the daily online journal

Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of the daily online journal

It is not only through our actions that we can give life meaning — insofar as we can answer life’s specific questions responsibly — we can fulfill the demands of existence not only as active agents but also as loving human beings: in our loving dedication to the beautiful, the great, the good. Should I perhaps try to explain for you with some hackneyed phrase how and why experiencing beauty can make life meaningful? I prefer to confine myself to the following thought experiment: imagine that you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favorite symphony, and your favorite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine; and now imagine that it would be possible (something that is psychologically so impossible) for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would agree with me if I declared that in this case you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like: “It would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!”

It is not only through our actions that we can give life meaning — insofar as we can answer life’s specific questions responsibly — we can fulfill the demands of existence not only as active agents but also as loving human beings: in our loving dedication to the beautiful, the great, the good. Should I perhaps try to explain for you with some hackneyed phrase how and why experiencing beauty can make life meaningful? I prefer to confine myself to the following thought experiment: imagine that you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favorite symphony, and your favorite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine; and now imagine that it would be possible (something that is psychologically so impossible) for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would agree with me if I declared that in this case you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like: “It would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!”