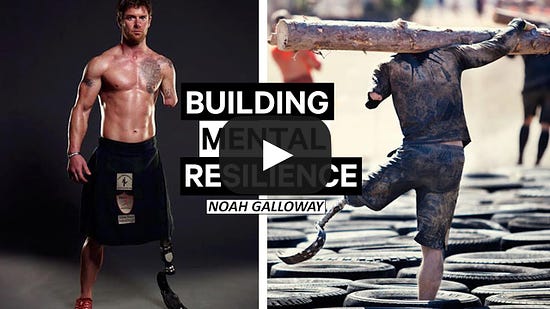

On Sept. 11, 2001, Noah Galloway was a college student in Birmingham, Alabama.

After watching the Twin Towers collapse, he went on a run to clear his mind. The next day, he dropped out of school and enlisted in the military at just 21 years old. Galloway's first deployment was during the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003.

He had finally found what he was looking for — the military had given him a sense of purpose. He served one deployment, and then he re-enlisted.

Three months into his second deployment in Iraq, Galloway was driving a Humvee when the vehicle ran over a tripwire that detonated a roadside bomb large enough to throw the entire armored vehicle through the air and into a canal adjacent to the road.

"Thankfully, we landed wheels down in the water," Galloway told The Profile. "They said the water was up to my chest, huge hole in my jaw, arm was taken off immediately."

This was Dec. 19, 2005. On Christmas Day, Galloway woke up at the Walter Reed Medical Center in Washington D.C. "I woke up unaware of where I was or how I got there," he says.

Soon, he would discover all that he had lost. The roadside bomb had taken his left arm, left leg, and military career.

Suddenly, Galloway was back in his home in Alabama with a new label: wounded veteran. The physical injuries were obvious, but it was the mental ones that haunted him. He fell into a deep depression and began drinking heavily.

"I didn't realize how bad my depression was until I came out of it," Galloway says. "It was such a bad place I was in."

After his marriage fell apart, Galloway was arrested for a DUI and spent 10 days in jail. He knew he had to do better, not only for himself but for his kids. So he worked on building mental resilience while strengthening his body until he dug himself out of the powerful grip of depression.

He went on to run ultra-races, marathons, and Tough Mudders. He appeared on the cover of Men's Health magazine and placed third on the TV show, "Dancing with the Stars." And still — he recognizes those accomplishments don't define him. They were just chapters in his life journey.

Galloway embodies everything The Profile stands for. It's about shedding the labels society has slapped on you and re-claiming the power to re-invent yourself — no matter your age, your current circumstance, or your past traumas.

Below is an excerpt of the interview, but I encourage you to hear his story in full here:

I recently wrote about the danger of labeling people. When you came back to the United States, you're still Noah Galloway, but to everyone else, you're now, "Noah Galloway, the wounded veteran."

GALLOWAY: Even to this day, I deal with that. I try to tell other veterans, "Be proud of the time you served, but that's a chapter in your life." In fact, my chapter was only five years. And I loved it. And I'm proud of it.

Here we are wanting to improve veteran suicide [rates], but when we talk about veterans, we act like that's all we are — crazy and we kill ourselves. You know what? NFL players have a high suicide rate. That's just as important as us. The entire country has a suicide issue we need to deal with. Don't label us as just that. When you label people, they will become what they're labeled.

I grew up in a town that was literally on the other side of the railroad tracks. I was on the bad part of town. I remember as a teenager, we were treated like we were the bad kids. So what did we do? We lived up to it.

There are so many veterans who are CEOs, business owners, and venture capitalists. Some of them do talk about being veterans, but it is often not the first label, and it's probably because they don't want to be put in a certain box, right?

Yes. There are so many musicians whose music I've been following only to realize, "Oh my gosh, you were in the military? You deployed? I had no idea."

You want to take pride in being a veteran, and no one wants to talk ill of veterans, but let's be real, no one's hiring us because of the way we're labeled.

Every movie portrays us as broken — and we're not. There are a lot of successful people. You know, I like to think I'm successful, and yes, being an injured veteran got me attention, so it's hard for me to argue that, but I don't want to just be that.

I've juggled being divorced and a good father to my three kids and managing life and fitness and everything else.

In you book, "Living With No Excuses," you write, "I'd sit at home and drink and smoke and sleep. That's all I did." How did you feel in those first months back as you're making your recovery?

Lost. Confused. I had found this career, and it was taken away. I had done manual labor before I got injured, so I was like, "What do I do now?"

I got re-married, rushed into a second marriage that didn't work out because I was in this dark place. And then I was this sad shell of a man. But I tried to hide it because I didn't want to admit I was scared and confused.

So you started drinking to dull those feelings.

I took pride that I got off all this medication, but all I started doing was self-medicating, and it was doing me no good. I was in denial. I didn't know how bad my depression was until I finally came out of it, realizing I needed to be a better father. It was such a bad place I was in.

You're at pretty much rock bottom, and one evening, you've been drinking and driving. You get pulled over by police. You've said before that the police officer who arrested you for a DUI actually saved your life. How so?

In a small town, you get pulled over, they see a Purple Heart tag, they see you're missing an arm and a leg, the war's a big deal in the news.

The night that I got that police officer who didn't know who I was and he did me a huge favor because I needed that. I ended up spending 10 days in the county jail because I made the judge mad and was held in contempt of court. It was a sad place. When I was locked up, I was in this county jail where there were people headed to the penitentiary.

I was talking to these guys, and I was like, "I can still recover from this." You know what I mean? I can turn this around. I don't need to keep going down this rabbit hole. It was that police officer and those guys I talked to that were a huge help.

You write: “One thing about my depression: I hid it very well. Now, looking back, it was pretty obvious. So I guess the more accurate statement is that the person I was hiding from the most was myself." Do you remember the moment when you recognized that?

Yes, I do. There was a full-length mirror in my bedroom. I would just look at it and see my injuries. I had been in fitness my entire life, now I was out of shape and I was injured. All these different things. It would make me angry, and it would be something I did just to stir the pot with my own emotions.

I was doing that one day, and then I walked out in the living room and saw my three kids sitting on the couch watching TV. I realized that to my two boys, I'm showing them what a man is, and that's what they're going to become one day. To my little girl, I'm showing her how a man's supposed to act, and that's what she'll look for one day. And that terrified me.

I turned and all of a sudden, it hit me like a ton of bricks. I knew I had to make changes, and I had to make them fast. I credit my kids for every bit of success I have. Without a doubt.

You have this mental framework that I can't get out of my head. Explain "The Al Bundy Effect."

Al Bundy, from Married With Children, is a depressed shoe salesman that is unhappy with life in general. The only time he gets excited is when he talks about scoring four touchdowns in a single football game back in high school. It's the only time he gets excited.

I see a lot of veterans — and other people do it — but I point out to veterans that you can't live in the past because you'll never be satisfied with what you're doing now. You'll never progress and challenge yourself again because you've peaked too soon. But you only peak when you decide you've peaked. So Al Bundy chose to peak in high school and never did anything else.

As a veteran, I served in the military, loved wearing the uniform, proud that I had that American flag patch on my arm, but it was a chapter in my life. One chapter.

The last couple of years, after being on Men's Health, Dancing With the Stars, and American Grit, I've traveled all over, people were excited to meet me, speeches everywhere, made all kinds of stupid money, and then everything stops. Well, what do we do now? Well, it's time to start another chapter.

It was a great run, I enjoyed it, but my life's not over. Whether I'm in the public eye or not, Noah Galloway's going to keep doing something whether people know it or not. My family and I are going to have a good time. We're going to work and do the next thing we have to.

I've tried to show my kids that. Hey, guess what? This Christmas isn't going to be as big as big as the other Christmases because dad took an 80% pay cut when everything stopped. But you know what? We're doing great, and it's OK. We're going to figure out what we're doing next.

It doesn't matter how old you are, you can start over. You can start a new thing.

—

THE PROFILE DOSSIER: On Wednesday, premium members received The Profile Dossier, a comprehensive deep-dive on a prominent individual. It featured Jim Koch, the self-made beer billionaire. Become a premium member and read it here.

THE WORLD'S MOST SUCCESSFUL: In this podcast episode, I discuss what I've learned from studying the world’s most successful people, including Elon Musk, Sara Blakely, Martha Stewart, Grant Achatz, Anthony Bourdain, and many others. Check it out here.

PROFILES.

— The man who builds impossible things[**HIGHLY RECOMMEND**]

— The athlete-turned-activist

— The man who found a million-dollar treasure

— The inspiring founder who lost his way

— The CEO trying to save traditional bookselling

— The obscure billion-dollar media giant

— The immigrant VCs who made a great bet

PEOPLE TO KNOW.

The man who builds impossible things: Mark Ellison is a carpenter savant, a welder, a sculptor, a contractor, a cabinetmaker, an inventor, and an industrial designer. He is the person billionaires hire to build impossible things. His least expensive projects cost around $5 million, but others can swell to $50 million or more. This is a delightful glimpse into the mind of a craftsman obsessed with perfecting his obsession. (The New Yorker)

“It’s all about ellipses and irrational numbers. It’s the language of music and art. It’s like life: nothing ever works out on its own.”

The athlete-turned-activist: After nearly two decades in the NBA, LeBron James has fully embraced that his talent on the court is a means to achieving something greater. This year, James played on in the bubble and led the Los Angeles Lakers to the NBA championship. He also increased his leverage and influence, and got deep-pocketed owners, fellow athletes, and fans around the world engaged directly with democracy. Here's how he channeled outrage into a plan of action. (TIME)

“Not only is he the best player, but he has the most powerful voice."

The man who found a million-dollar treasure: A decade ago, art dealer and author Forrest Fenn hid a treasure chest containing valuables estimated to be worth at least a million dollars. Not long after, he published a memoir, which included a mysterious poem that, if solved, would lead searchers to the treasure. Since the hunt began, thousands of searchers had gone out in pursuit—at least five of them losing their lives in the process. Meet Jack Stuef, the 32-year-old medical student who finally solved the case this year. (Outside Magazine)

“If I didn’t find it, I would look kind of like an idiot. And maybe I didn’t want to admit to myself what a hold it had on me.”

The inspiring founder who lost his way: This is yet another profile on the late Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh. His close friends say his death was the culmination of a more than six-month downward spiral and increasingly extreme behavior. Hsieh became fixated on trying to figure out what his body could live without. He starved himself of food, whittling away to under 100 pounds; he tried not to urinate; and he deprived himself of oxygen, turning toward nitrous oxide, which can induce hypoxia. Just a small reminder to check in on your friends during this difficult year. (WSJ; reply to this email if you can't access the article)

“When you need to party, you party. When you need to produce, you produce."

The CEO trying to save traditional bookselling: Barnes & Noble's new CEO James Daunt is abandoning the strategy that made it a bookselling behemoth two decades ago—uniformity. Instead, the company is empowering store managers to curate their shelves based on local tastes. Here's why ceding control is central to Daunt's strategy to keep Barnes & Noble alive. (WSJ; reply to this email if you can't access the article)

“If you get your stores right, your online sales will follow. If your stores are crap, your online will be as well.”

COMPANIES TO WATCH.

The obscure billion-dollar media giant: OnlyFans has grown into one of the biggest media businesses hiding in plain sight. Although the company has been largely associated with adult models and porn stars, it's evolving to encompass more types of content creators. It now boasts 85 million users, upward of 1 million creators, and will generate more than $2 billion in sales this year, of which it keeps about 20%. Here's why OnlyFans skyrocketed in popularity during the pandemic. (Bloomberg)

“The creator community is incredibly diverse. There are just so many creators from so many genres, whether it’s gaming, fitness, fashion, beauty.”

The immigrant VCs who made a great bet: Pear VC is a venture firm launched by two immigrants that stands to return its entire $51 million first fund a few times over from one of its very first bets. In 2013, Pear co-founders Mar Hershenson and Pejman Nozad found an interesting new startup called DoorDash. They invested a total of about $1.9 million. When DoorDash went public on Wednesday, their $1.9 million turned into more than $440 million. Meet the relentless VC duo. (Forbes)

"We kept going, waking up every morning and asking why entrepreneurs should be partnered with us. And we still ask that question.”

This installment of The Profile is free for everyone. If you would like to get full access to all of the recommendations, including today’s audio and video sections, sign up below.

AUDIO TO HEAR.

Jerry Seinfeld on the creative process: Comedian Jerry Seinfeld describes his early-career writing sessions like "pushing against the wind in soft, muddy ground with a wheelbarrow full of bricks." To be good at standup comedy, he says, you need to learn to be a writer. In this podcast episode, Seinfeld explains the two phases of his creative process that have allowed him to become a master of his craft. (Link available to premium members.)

Tim Cook on the future of fitness: Apple CEO Tim Cook is obsessed with fitness. Even though he's one of the busiest CEOs in the world, Cook never misses a workout because even he understands the importance of disconnecting from technology and stepping away from the screen. "I'm off grid for [my workout]," he says. "And I am religious about doing that regardless of what may be going on at the time." With recent news that Apple is introducing its virtual training platform Fitness+, here's why Cook says the company is moving into the online training space in a major way. (Link available to premium members.)

Natalie Portman on the danger of sexualizing young girls: In this podcast, actress Natalie Portman explains how being sexualized as a child star — she started acting at age 12— affected her career and personal development. "Being sexualized as a child, I think, took away from my own sexuality, because it made me afraid," she says. As a result, she developed defenses against unwanted attention by choosing more serious, darker roles. (Link available to premium members.)

VIDEOS TO SEE.

The mountaineers who found calm in the suffering: For Hilaree Nelson and Jim Morrison, skiing isn’t a choice. It’s the only option. In 2018, they made history after completing the first ski descent of the 27,940-foot Lhotse, the fourth-highest mountain in the world. But what’s even crazier than the feat itself is the why behind it. This is a story that will stay with you for long after you’ve heard it. (Link available to premium members.)

Daniel Ek on his entrepreneurial playbook: In this interview from 2012, you get a glimpse inside Daniel Ek's mind at a point in time when Spotify was still evolving and figuring it out. Even though he started his first company at age 14, Ek explains that he's never really thought of himself as an entrepreneur. He didn't think he was starting "companies," rather, he saw himself as just working on a series of problems that needed to be solved. This is a good one. (Link available to premium members.)

👉 Members receive the best longform article, audio, and video recommendations every Sunday. Join the club by signing up below: