I have moved through this fourteenth year of Brain Pickings — a devastating year for the world we share, a discomposing year for my private world — by leaning on the writings and wisdom of the long-gone for succor, for calibration of perspective, for the beauty that makes life livable. Of the few books published this year that I did read — many fewer than ordinary years — here are twenty I trust would furnish such splendor and succor for generations to come. Think of the selection not as a hierarchy but as a bookshelf, organized by an internal logic that need not make sense to anyone outside the home and the mind in which the bookshelf is suspended.

Art by Violeta Lópiz from A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader. Available as a print, benefiting the New York Public Library.

I am not and have never been a reviewer of books — a person who surveys the landscape of literature with the goal of evaluating its features. I am and have always been a solitary sojourner who relishes curious excursions hither and dither, guided by a thoroughly subjective inner compass, wandering the wilderness of words by pleasant deviations from the common trail.

These are my footsteps.

Reading Zadie Smith is always a rapture, but it has been especially rapturous to press the mind’s ear to her Intimations (public library) this year — a slender collection of six symphonic essays spanning love, death, justice, creativity, identity — everything worth thinking about and writing about, everything we live with and live for.

Reading Zadie Smith is always a rapture, but it has been especially rapturous to press the mind’s ear to her Intimations (public library) this year — a slender collection of six symphonic essays spanning love, death, justice, creativity, identity — everything worth thinking about and writing about, everything we live with and live for.

The book was inspired by Smith’s first encounter with Marcus Aurelius’s classic Meditations, on which she leaned to steady herself in these staggering times but which failed to make of her a Stoic, driving her, as the world’s gaps and failings drive us restive makers, to make what meets the unmet need — a contemporary counterpart to these ancient private meditations of timeless public resonance. (We cannot, we must not, after all, expect a white male monarch — however penetrating his insight into human nature, whatever the similitudes of that elemental nature across cultures and civilizations — to speak for and to all of humanity across all of time.)

Zadie Smith (Photograph by Dominique Nabokov)

In the laconic foreword, Smith reflects on the essential insight the Meditations gave her in failing to give her practical succor:

Talking to yourself can be useful. And writing means being overheard.

Talking to yourself can be useful. And writing means being overheard.

These intimations she lets us overhear are blazing evidence that every artist’s art is their coping mechanism, their floatation device for the slipstream of uncertainty we call life — evidence that a great artist makes of it a raft large enough to fit more of us, robust enough to carry us across the cascades of time and understanding.

For a taste of the book, all the author’s proceeds from which go toward the Equal Justice Initiative and New York’s COVID-19 emergency relief fund, here is Smith on love, habit, and creativity.

Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life (public library) by Radiolab alum and Invisibilia co-creator Lulu Miller is a surprising book, an unclassifiable book — my kind of book. It appears to be, and to an impressive scholarly extent is, about David Starr Jordan — the founder of Stanford University, a brilliant ichthyologist and a deluded eugenicist. But while his strange and cautionary story backbones the book, it is ribbed with larger ideas: questions about the vain and touchingly human impulse to manufacture order out of elemental chaos, about the colossal blind spots that plague even the greatest visionaries, about the limiting yet necessary artifice of categories by which we attempt to navigate a world of continua and indivisibilia, about our pursuit of timeless truth against the backdrop of our own inevitable and heartbreaking temporality.

Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life (public library) by Radiolab alum and Invisibilia co-creator Lulu Miller is a surprising book, an unclassifiable book — my kind of book. It appears to be, and to an impressive scholarly extent is, about David Starr Jordan — the founder of Stanford University, a brilliant ichthyologist and a deluded eugenicist. But while his strange and cautionary story backbones the book, it is ribbed with larger ideas: questions about the vain and touchingly human impulse to manufacture order out of elemental chaos, about the colossal blind spots that plague even the greatest visionaries, about the limiting yet necessary artifice of categories by which we attempt to navigate a world of continua and indivisibilia, about our pursuit of timeless truth against the backdrop of our own inevitable and heartbreaking temporality.

Miller writes in the splendid prose-poem of an introduction:

Picture the person you love the most. Picture them sitting on the couch, eating cereal, ranting about something totally charming, like how it bothers them when people sign their emails with a single initial instead of taking those four extra keystrokes to just finish the job —

Picture the person you love the most. Picture them sitting on the couch, eating cereal, ranting about something totally charming, like how it bothers them when people sign their emails with a single initial instead of taking those four extra keystrokes to just finish the job —

Chaos will get them.

Chaos will crack them from the outside — with a falling branch, a speeding car, a bullet — or unravel them from the inside, with the mutiny of their very own cells. Chaos will rot your plants and kill your dog and rust your bike. It will decay your most precious memories, topple your favorite cities, wreck any sanctuary you can ever build.

It’s not if, it’s when. Chaos is the only sure thing in this world. The master that rules us all. My scientist father taught me early that there is no escaping the Second Law of Thermodynamics: entropy is only growing; it can never be diminished, no matter what we do.

A smart human accepts this truth.

A smart human does not try to fight it. But one spring day in 1906, a tall American man with a walrus mustache dared to challenge our master.

His name was David Starr Jordan, and in many ways, it was his day job to fight Chaos. He was a taxonomist, the kind of scientist charged with bringing order to the Chaos of the earth by uncovering the shape of the great tree of life — that branching map said to reveal how all plants and animals are interconnected. His specialty was fish, and he spent his days sailing the globe in search of new species. New clues that he hoped would reveal more about nature’s hidden blueprint.

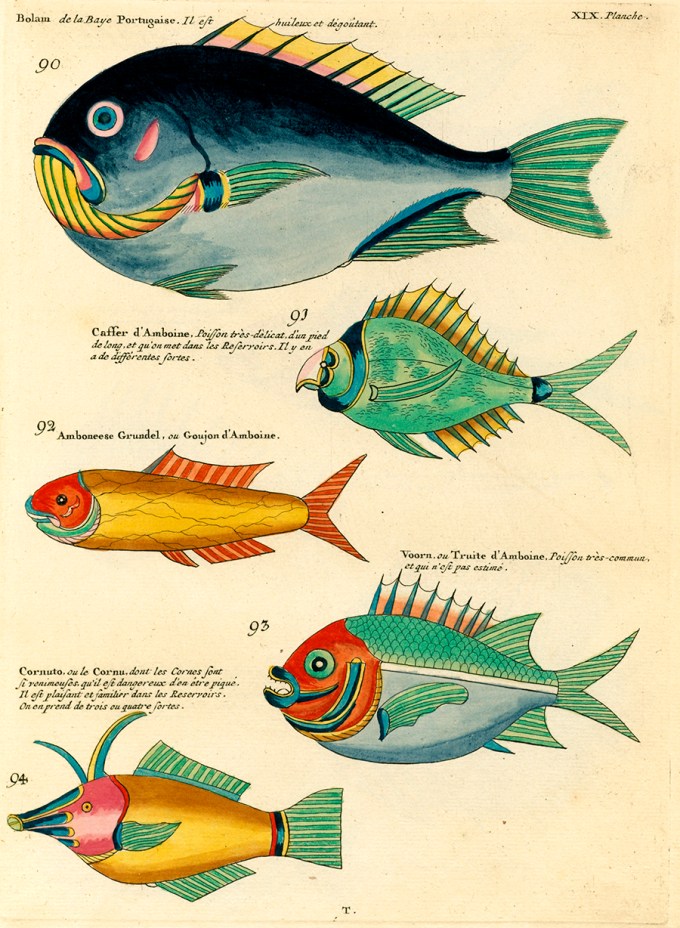

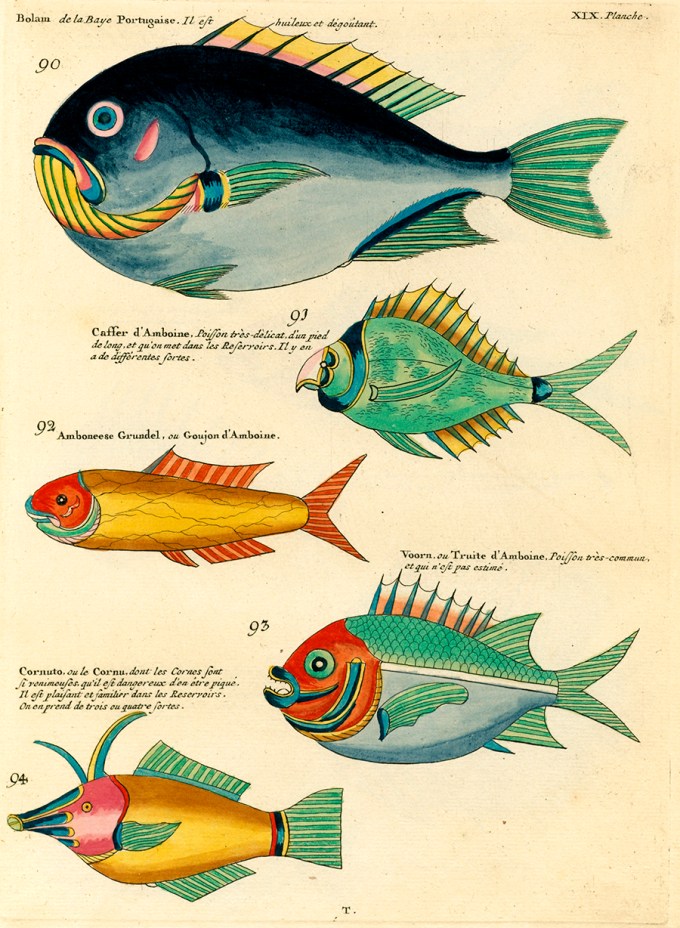

One of Louis Renard’s 1719 illustrations from the world’s first color encyclopedia of fishes. Available as a print and as a face mask.

The dazzling scientific story — the story of why the very notion of fish as a category of creature is entirely invented, uncorroborated by nature — becomes a lens for questioning the broader binaries we have accepted as givens, as fundaments of nature rather than the human artifacts that they are. It becomes the framework for a tender personal story, part meditation and part memoir — an elegy for Miller’s father and everything he taught her about navigating the world, a reckoning with the dangerous detours she took in navigating her own heart, a love letter to its unexpected port in the woman who became her wife.

THE SELECTED WORKS OF AUDRE LORDE

|

This is the precarious balance of a thriving society: exposing the fissures and fractures of democracy, but then, rather than letting them gape into abysses of cynicism, sealing them with the magma of lucid idealism that names the alternatives and, in naming them, equips the entire supercontinent of culture with a cartography of action. “Words have more power than any one can guess; it is by words that the world’s great fight, now in these civilized times, is carried on,” Mary Shelley wrote as she championed the courage to speak up against injustice two hundred years ago, amid a world that commended itself for being civilized while barring people like Shelley from access to education, occupation, and myriad other civil dignities on account of their chromosomes, and barring people just a few shades darker than her from just about every human right on account of their melanin.

This is the precarious balance of a thriving society: exposing the fissures and fractures of democracy, but then, rather than letting them gape into abysses of cynicism, sealing them with the magma of lucid idealism that names the alternatives and, in naming them, equips the entire supercontinent of culture with a cartography of action. “Words have more power than any one can guess; it is by words that the world’s great fight, now in these civilized times, is carried on,” Mary Shelley wrote as she championed the courage to speak up against injustice two hundred years ago, amid a world that commended itself for being civilized while barring people like Shelley from access to education, occupation, and myriad other civil dignities on account of their chromosomes, and barring people just a few shades darker than her from just about every human right on account of their melanin.

Shelley laced her novels with the exquisite prose-poetry of conviction, of vision that saw far beyond the horizons of her time and carried generations along the vector of that vision to shift the status quo into new frontiers of possibility. A century and a half after her, Audre Lorde (February 18, 1934–November 17, 1992) — another woman of uncommon courage of conviction and potency of vision — expanded another horizon of possibility by the power of her words and her meteoric life. Lorde was a poet in both the literal sense at its most stunning and the largest, Baldwinian sense — “The poets (by which I mean all artists),” wrote her contemporary and coworker in the kingdom of culture James Baldwin, “are finally the only people who know the truth about us. Soldiers don’t. Statesmen don’t… Only poets.” Lorde understood the power of poetry — the power of words mortised into meaning and tenoned into truth, truth about who we are and who we are capable of being — and she wielded that power to pivot an imperfect world closer to its highest potential.Nowhere does that potency of understanding live with more focused force than in her 1977 manifesto of an essay “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” which opens The Selected Works of Audre Lorde (public library) — the excellent collection of poetry and prose, edited and with a foreword by the unstoppable Roxane Gay.

Audre Lorde (Photograph: Robert Alexander)

Lorde, who resolved to live her life as a burst of light as she faced her death, and so lived it, writes:

The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are — until the poem — nameless and formless, about to be birthed, but already felt. That distillation of experience from which true poetry springs births thought as dream births concept, as feeling births idea, as knowledge births (precedes) understanding.

The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are — until the poem — nameless and formless, about to be birthed, but already felt. That distillation of experience from which true poetry springs births thought as dream births concept, as feeling births idea, as knowledge births (precedes) understanding.

With an eye to how poetry uniquely anneals us by bringing us into intimate contact with those parts of ourselves we least understand and therefore most fear, Lorde adds:

As we learn to bear the intimacy of scrutiny and to flourish within it, as we learn to use the products of that scrutiny for power within our living, those fears which rule our lives and form our silences begin to lose their control over us.

As we learn to bear the intimacy of scrutiny and to flourish within it, as we learn to use the products of that scrutiny for power within our living, those fears which rule our lives and form our silences begin to lose their control over us.

For more from the book, see Lorde on the courage to feel as an antidote to fear.

“To decide whether life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question of philosophy,” Albert Camus wrote in his classic 119-page essay The Myth of Sisyphus in 1942. “Everything else… is child’s play; we must first of all answer the question.”

“To decide whether life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question of philosophy,” Albert Camus wrote in his classic 119-page essay The Myth of Sisyphus in 1942. “Everything else… is child’s play; we must first of all answer the question.”

Sometimes, life asks this question not as a thought experiment but as a gauntlet hurled with the raw brutality of living.

That selfsame year, the young Viennese neurologist and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl (March 26, 1905–September 2, 1997) was taken to Auschwitz along with more than a million human beings robbed of the basic right to answer this question for themselves, instead deemed unworthy of living. Some survived by reading. Some through humor. Some by pure chance. Most did not. Frankl lost his mother, his father, and his brother to the mass murder in the concentration camps. His own life was spared by the tightly braided lifeline of chance, choice, and character.

Viktor Frankl

A mere eleven months after surviving the unsurvivable, Frankl took up the elemental question at the heart of Camus’s philosophical parable in a set of lectures, which he himself edited into a slim, potent book published in Germany in 1946, just as he was completing Man’s Search for Meaning.

As our collective memory always tends toward amnesia and erasure — especially of periods scarred by civilizational shame — these existential infusions of sanity and lucid buoyancy fell out of print and were soon forgotten. Eventually rediscovered — as is also the tendency of our collective memory when the present fails us and we must lean for succor on the life-tested wisdom of the past — they are now published in English for the first time as Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything (public library).

In a sentiment that bellows from the hallways of history into the great vaulted temple of timeless truth, he writes:

Everything depends on the individual human being, regardless of how small a number of like-minded people there is, and everything depends on each person, through action and not mere words, creatively making the meaning of life a reality in his or her own being.

Everything depends on the individual human being, regardless of how small a number of like-minded people there is, and everything depends on each person, through action and not mere words, creatively making the meaning of life a reality in his or her own being.

Read more here.

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ALICE B. TOKLAS

|

It is not often that one encounters a great love letter to a great love, composed by someone outside the private world of that love, serenading it across the spacetime of epochs and experiences. In my many years of dwelling in the lives and loves and letters of beloved artists, scientists, and writers, I have encountered none more splendid than The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas Illustrated (public library) by Maira Kalman — an artist who uses her paintbrush the way Stein used her pen, as the instrument of an imagination tilted pleasantly askance from the plane of common thought.

It is not often that one encounters a great love letter to a great love, composed by someone outside the private world of that love, serenading it across the spacetime of epochs and experiences. In my many years of dwelling in the lives and loves and letters of beloved artists, scientists, and writers, I have encountered none more splendid than The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas Illustrated (public library) by Maira Kalman — an artist who uses her paintbrush the way Stein used her pen, as the instrument of an imagination tilted pleasantly askance from the plane of common thought.

Gertrude Stein published The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas in 1933, when she was fifty-nine and Alice fifty-six. She had written it at an astonishing pace the previous autumn. Like Alice disguised her memoir of their love as a cookbook, Gertrude disguised hers as an “autobiography” of the beloved under the lover’s byline. It wasn’t, of course, Alice’s autobiography, or even her biography — rather, it was the biography of their love, of early-twentieth-century Paris, of the community of visionary artists and writers who orbited the couple and who came to be known as the Lost Generation — a term Gertrude Stein coined — as they found themselves, in every sense of the term, at Alice and Gertrude’s salons.

The book begins, naturally, not at Alice’s birth but at her fateful first encounter with Gertrude and her coral brooch the day Alice, thirty-three, arrived in Paris as an American expatriate — a moment she eventually recounted in such deeply felt detail on the pages of her slender actual autobiography, animated by a bereavement that never left her in the twenty “empty” years by which she outlived the love of her life.

Kalman introduces the book with her spare and singular poetics:

Alice met Gertrude.

Alice met Gertrude.

Gertrude met Alice.

Gertrude with her big body.

Big presence.

Alice, a little bird

with a mustache.

And that was that.

A coup de foudre

as we say.

Gertrude wrote this book of

their lives

through Alice’s eyes.

And here it is (happily)

with paintings

to illustrate how it was.

Savor more here.

BLACK HOLE SURVIVAL GUIDE

|

“I see that the elementary laws never apologize,” Walt Whitman wrote in the golden age of observational astronomy. “The bright suns I see and the dark suns I cannot see are in their place” — an astonishing sentiment by a rare seer who bent his gaze half a century beyond his era’s horizons of knowledge. Not long after Whitman’s death, the mind outpaced the eye to see, not with a telescope but with mathematics, those “dark suns” — those cinches in the basic fabric of reality that confound space, confound time, and confirm Whitman’s augury that “the celestial laws are yet to be work’d over and rectified.”

“I see that the elementary laws never apologize,” Walt Whitman wrote in the golden age of observational astronomy. “The bright suns I see and the dark suns I cannot see are in their place” — an astonishing sentiment by a rare seer who bent his gaze half a century beyond his era’s horizons of knowledge. Not long after Whitman’s death, the mind outpaced the eye to see, not with a telescope but with mathematics, those “dark suns” — those cinches in the basic fabric of reality that confound space, confound time, and confirm Whitman’s augury that “the celestial laws are yet to be work’d over and rectified.”

Denied and derided for decades by some of the most titanic minds of the century, black holes began as a mathematical reckoning — tentative, treacherous, transcendent. Suddenly, reality was broken and reality was beautiful.

The immense ripples of that reckoning are what astrophysicist Janna Levin explores in Black Hole Survival Guide (public library), dappled with gorgeous ghostly paintings by artist and fellow Whitman celebrator Lia Halloran — a poetic primer on relativity, pocket-sized like the second edition of Leaves of Grass, which Whitman redesigned to be carried on the breast and in which he declared that “the known universe has one complete lover and that is the greatest poet.”

Art by Lia Halloran from Black Hole Survival Guide by Janna Levin

The cheeky title — we learn quickly that nothing can escape a black hole except the black hole itself, slipping out of the very reality its existence warps — is soon revealed as a clever conceit, a Trojan horse for some serious, scrumptious science that bends our basic assumptions. What emerges is a lyrical and authoritative story of strangeness as a portal to truth, tracing how black holes went from “the unwanted product of the plasticity of space and time, grotesque and extreme deformations, grim instabilities” to “a laboratory for the exploration of the farthest reaches of the mind,” things that are no-things and in their non-thingness “undermine notions of reality, but ameliorate the pain with a mind-searing vision of nature.”

Black holes are so magnetic largely because they defy our animal intuitions about reality, about the everythingness of everything. She writes:

When in pursuit of a black hole, you are not looking for a material object. A black hole can masquerade as an object, but it is really a place, a place in space and time. Better: a black hole is a spacetime.

When in pursuit of a black hole, you are not looking for a material object. A black hole can masquerade as an object, but it is really a place, a place in space and time. Better: a black hole is a spacetime.

[…]

Shed the impression of the black hole as a dense crush of matter. Accept the black hole as a bare event horizon, a curved empty spacetime, a sparse vacuity… A glorious void, an empty venue, an extreme, spare stage, markedly austere but, yes, able to support big drama when the stage is occupied. Black holes are a place in space and they barricade their secrets.

Art by Lia Halloran from Black Hole Survival Guide by Janna Levin

Undergirding the century-long quest to unravel those secrets is a testament to the fundaments of creativity — a celebration of deliberate constraint as the fulcrum of revolutions. In a sentiment evocative of the last line in the late, great astronomer and poet Rebecca Elson’s gorgeous poem “Explaining Relativity,” she writes:

The limits are the scaffolding enabling creativity. Limits can be worthy adversaries that galvanize our best, most inventive, most agile natures.

The limits are the scaffolding enabling creativity. Limits can be worthy adversaries that galvanize our best, most inventive, most agile natures.

Radiating from this lyrical odyssey of science, from this savage passion for understanding, is the subtle and stubborn insistence that the elementary laws are not something separate from us, are not alluring abstractions, are not playthings of the mind, but are the making and unmaking of us sensecrafting creatures — creatures that cohered from particles that cohered into molecules that cohered into minds capable of parsing information, capable of wresting from it conjectures about the elementary laws, capable of writing poems and postulates about the nature of reality and our place in it. That we think, and how we think, is our only means of survival.

Art by Lia Halloran from Black Hole Survival Guide by Janna Levin

When the Voyager sailed into the unknown to take its pioneering photographic survey of our cosmic neighborhood, Carl Sagan petitioned NASA to indulge his inspired, entirely unscientific, entirely poetic idea of turning the spacecraft’s cameras back on Earth from the outer edges of the Solar System. That grainy, transcendent photograph of our “mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam” became the central poetic image of his now-iconic Pale Blue Dot meditation on our cosmic place and destiny, which in turn inspired Maya Angelou’s “A Brave and Startling Truth” — the staggering poem that flew to space aboard the Orion spacecraft, inviting a fractured humanity to reach beyond our divisive ideologies and see ourselves afresh “on this small and drifting planet,” to face our capacities and contradictions, and finally see that “we are the possible, we are the miraculous, the true wonder of this world.”

When the Voyager sailed into the unknown to take its pioneering photographic survey of our cosmic neighborhood, Carl Sagan petitioned NASA to indulge his inspired, entirely unscientific, entirely poetic idea of turning the spacecraft’s cameras back on Earth from the outer edges of the Solar System. That grainy, transcendent photograph of our “mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam” became the central poetic image of his now-iconic Pale Blue Dot meditation on our cosmic place and destiny, which in turn inspired Maya Angelou’s “A Brave and Startling Truth” — the staggering poem that flew to space aboard the Orion spacecraft, inviting a fractured humanity to reach beyond our divisive ideologies and see ourselves afresh “on this small and drifting planet,” to face our capacities and contradictions, and finally see that “we are the possible, we are the miraculous, the true wonder of this world.”

A generation later, this spirit comes ablaze anew in If You Come to Earth (public library) by Sophie Blackall — one of the most beloved picture-book makers of our time and one of those rare artists, so few in any given generation, whose work of great talent and great tenderness is bound to be cherished for epochs to come.

Told in the form of a letter from a child to an alien visitor — a particular child named Quinn, whom Sophie met while traveling around the world with UNICEF and Save the Children, and whose uncommon imagination fomented hers — the story is populated by drawings of other real-life children she met on her travels in India, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, a particular class of twenty-three kids she befriended in a Brooklyn public school, and her own real-life friends and neighbors. Animated by the children’s wild, wondrous, touching ideas about the most important things to communicate about our improbable, miraculous world to a visitor from another, the book radiates the spirit of the Voyager’s Golden Record — a poetic capsule of humanism and collaborative meaning-making, the true purpose of which is not to encode for some interstellar other but to decode for us who and what we are.

See more here.

The poetry of Jane Hirshfield — a poet of optimism and of lucidity, a champion of science and an ordained Buddhist, a poet who could write “So few grains of happiness / measured against all the dark / and still the scales balance,” a poet who can balance and steady us against those times when we “go to sleep in one world and wake in another” — has salved and saved my life again and again across many seasons and epochs of being. Her collection Ledger (public library) has been nothing less than a lifeline this year.

The poetry of Jane Hirshfield — a poet of optimism and of lucidity, a champion of science and an ordained Buddhist, a poet who could write “So few grains of happiness / measured against all the dark / and still the scales balance,” a poet who can balance and steady us against those times when we “go to sleep in one world and wake in another” — has salved and saved my life again and again across many seasons and epochs of being. Her collection Ledger (public library) has been nothing less than a lifeline this year.

For a taste, here is Hirshfield reading one of the poems from the book, “Today, Another Universe,” at the 2020 Universe in Verse:

TODAY, ANOTHER UNIVERSE

TODAY, ANOTHER UNIVERSE

by Jane Hirshfield

The arborist has determined:

senescence beetles canker

quickened by drought

but in any case

not prunable not treatable not to be propped.

And so.

The branch from which the sharp-shinned hawks and their mate-cries.

The trunk where the ant.

The red squirrels’ eighty-foot playground.

The bark cambium pine-sap cluster of needles.

The Japanese patterns the ink-net.

The dapple on certain fish.

Today, for some, a universe will vanish.

First noisily,

then just another silence.

The silence of after, once the theater has emptied.

Of bewilderment after the glacier,

the species, the star.

Something else, in the scale of quickening things,

will replace it,

this hole of light in the light, the puzzled birds swerving around it.

Five years after H Is for Hawk, which was among my favorite books of its year and remains among my favorite books of all years, Helen Macdonald returns with Vesper Flights (public library) — a cabinet of curiosities containing forty-one essays of kaleidoscopic subject range, from mushrooms to bird migration to Mars, focused by Macdonald’s singular sensibility of reverencing the natural world on its own terms and at the same time drawing from it illuminations of human nature and the human world — an essay about fungi and foraging exposing how the categories we superimpose on a complex world in order to comprehend it become blinders of understanding; an essay about the murmurations of starlings parlaying into a moving micro-memoir of Macdonald’s encounter with a young Syrian refugee; an essay about solar eclipses contouring questions of the self as a function of time and place rather than an inherent totality of being, casting a sidewise gleam of insight into the puzzling psychology of denial by which our species remains unwilling to course-correct its ecologically catastrophic course.

Five years after H Is for Hawk, which was among my favorite books of its year and remains among my favorite books of all years, Helen Macdonald returns with Vesper Flights (public library) — a cabinet of curiosities containing forty-one essays of kaleidoscopic subject range, from mushrooms to bird migration to Mars, focused by Macdonald’s singular sensibility of reverencing the natural world on its own terms and at the same time drawing from it illuminations of human nature and the human world — an essay about fungi and foraging exposing how the categories we superimpose on a complex world in order to comprehend it become blinders of understanding; an essay about the murmurations of starlings parlaying into a moving micro-memoir of Macdonald’s encounter with a young Syrian refugee; an essay about solar eclipses contouring questions of the self as a function of time and place rather than an inherent totality of being, casting a sidewise gleam of insight into the puzzling psychology of denial by which our species remains unwilling to course-correct its ecologically catastrophic course.

Total eclipse of 1878, one of Étienne Léopold Trouvelot’s groundbreaking astronomical drawings. (Available as a print and as a face mask, with proceeds benefiting the endeavor to build New York City’s first public observatory.)

Macdonald writes in the introduction:

Someone once told me that every writer has a subject that underlies everything they write. It can be love or death, betrayal or belonging, home or hope or exile. I choose to think that my subject is love, and most specifically love for the glittering world of non-human life around us. Before I was a writer I was a historian of science, which was an eye-opening occupation. We tend to think of science as unalloyed, objective truth, but of course the questions it has asked of the world have quietly and often invisibly been inflected by history, culture and society. Working as a historian of science revealed to me how we have always unconsciously and inevitably viewed the natural world as a mirror of ourselves, reflecting our own world-view and our own needs, thoughts and hopes. Many of the essays here are exercises in interrogating such human ascriptions and assumptions. Most of all I hope my work is about a thing that seems to me of the deepest possible importance in our present-day historical moment: finding ways to recognise and love difference. The attempt to see through eyes that are not your own. To understand that your way of looking at the world is not the only one. To think what it might mean to love those that are not like you. To rejoice in the complexity of things.

Someone once told me that every writer has a subject that underlies everything they write. It can be love or death, betrayal or belonging, home or hope or exile. I choose to think that my subject is love, and most specifically love for the glittering world of non-human life around us. Before I was a writer I was a historian of science, which was an eye-opening occupation. We tend to think of science as unalloyed, objective truth, but of course the questions it has asked of the world have quietly and often invisibly been inflected by history, culture and society. Working as a historian of science revealed to me how we have always unconsciously and inevitably viewed the natural world as a mirror of ourselves, reflecting our own world-view and our own needs, thoughts and hopes. Many of the essays here are exercises in interrogating such human ascriptions and assumptions. Most of all I hope my work is about a thing that seems to me of the deepest possible importance in our present-day historical moment: finding ways to recognise and love difference. The attempt to see through eyes that are not your own. To understand that your way of looking at the world is not the only one. To think what it might mean to love those that are not like you. To rejoice in the complexity of things.

[…]

What science does is what I would like more literature to do too: show us that we are living in an exquisitely complicated world that is not all about us. It does not belong to us alone. It never has done.

Rejoice in some of the complexity here.

“All things are so very uncertain, and that’s exactly what makes me feel reassured,” says Too-ticky, trying to comfort the lost and frightened Moomintroll under the otherworldly light of the aurora borealis.

“All things are so very uncertain, and that’s exactly what makes me feel reassured,” says Too-ticky, trying to comfort the lost and frightened Moomintroll under the otherworldly light of the aurora borealis.

A decade after Tove Jansson (August 9, 1914–June 27, 2001) dreamt up her iconic Moomin series — one of those works of philosophy disguised as children’s books, populated by characters with the soulful wisdom of The Little Prince, the genial sincerity of Winnie-the-Pooh, and the irreverent curiosity of the Peanuts — she dreamt up Too-ticky, the sage of Moominvalley, warmhearted and eccentric and almost unbearably lovable.

Too-ticky came aglow in Jansson’s artistic imagination from the same spark that galvanized Emily Dickinson’s poetry — her adoration of the woman who was already becoming the love of her life, the woman to whom she was already writing, “I long to read more in the book of you.”

Tove Jansson, 1956 (Tove Janssons arkiv / University of Minnesota Press)

At the 1955 Christmas party of Helsinki’s Artists’ Guild, Jansson found herself drawn to the record player, impelled to take over the evening’s music. Another artist — the Seattle-born Finnish engraver, printmaker, and graphic arts pioneer Tuulikki “Tooti” Pietilä — was impelled to do the same. They shared the jubilant duty. I picture the two of them at the turntable, sipping spiced wine in rapt, bobbing deliberation over which of the year’s hits to put on next — the year when rock and roll had just been coined, the year of Nat King Cole’s “If I May,” Elvis’s “Baby Let’s Play House,” and Doris Day’s “Love Me or Leave Me.” I picture them glancing at each other with the thrill of that peculiar furtive curiosity edged with longing, having not a glimmering sense — for we only ever recognize the most life-altering moments in hindsight — that they were in the presence of great love, a love that would last a lifetime. Tove was forty-one, Tooti thirty-eight. They would remain together for the next half century, until death did them part.

The tender delirium of their early love and the magmatic core of their lifelong devotion emanate from the pages of Letters from Tove (public library) — the altogether wonderful collection of Jansson’s correspondence with friends, family, and other artists, spanning her meditations on the creative process, her exuberant cherishment of the natural world and of what is best in human beings, her unfaltering love for Tooti. What emerges, above all, is the radiant warmth of her personhood — this person of such uncommon imagination, warmhearted humor, and stubborn buoyancy of spirit, always so thoroughly herself, who as a young woman had declared to her mother:

I’ve got to become free myself if I’m to be free in my painting.

I’ve got to become free myself if I’m to be free in my painting.

Read more here.

Decades before Simone de Beauvoir contemplated how chance and choice converge to make us who we are from the fortunate platform of old age, the eighteen-year-old Sylvia Plath — who never reached that fortunate platform, her life felled by the same conspiracy of chance and choice — contemplated these indelible forces in the guise of free will, writing in her journal that “there is such a narrow crack of it for man to move in, crushed as he is from birth by environment, heredity, time and event and local convention.”

Decades before Simone de Beauvoir contemplated how chance and choice converge to make us who we are from the fortunate platform of old age, the eighteen-year-old Sylvia Plath — who never reached that fortunate platform, her life felled by the same conspiracy of chance and choice — contemplated these indelible forces in the guise of free will, writing in her journal that “there is such a narrow crack of it for man to move in, crushed as he is from birth by environment, heredity, time and event and local convention.”

Two generations later, Maria Konnikova entered this eternal conundrum via an improbable path half chosen and half chanced into, emerging with insights into the paradoxes of chance and control, which neither strand alone could have afforded.

Having devoted five years of doctoral work, with the creator of the famous Marshmallow Experiment as her advisor, to designing and performing psychology experiments probing how people’s perception of control in situations dictated by pure chance shapes decision-making and outcomes, she was suddenly life-thrust into a much more intimate empiricism. A period of successive losses rendered her the sole bread-winner of a family as a mysterious malady savaged her body without warning, gnawing at the fundaments of consciousness.

In the midst of this maelstrom, she became interested in the world of poker. She entered it as a psychologist on a philosophical inquiry — how often are we actually in control when we think we are, how do we navigate uncertain situations with incomplete information, and how can we ever separate the product of our own efforts from the strokes of randomness governing the universe? She emerged an unexpected master of the game, master of her own mind in an entirely new way.

The record of that experience became The Biggest Bluff: How I Learned to Pay Attention, Master Myself, and Win (public library) — an inspired investigation of “the struggle for balance on the spectrum of luck and control in the lives we lead, and the decisions we make,” partway between memoir, primer on the psychology of decision-making, and playbook for life.

One of Salvador Dalí’s forgotten folios for a rare edition Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Having previously written about the psychology of confidence through the lens of con artists and the psychology of creativity through the lens of Sherlock Holmes, she takes the same singular approach of erudition and perspicacity to the improbable test-bed of poker, lacing her elegant primers on probability and game theory with perfectly illustrative invocations of Dostoyevsky, Epictetus, Dawkins, Ephron, Kant.

More than half a century after W. I. B. Beveridge observed in the undervalued treasure The Art of Scientific Investigation that “although we cannot deliberately evoke that will-o’-the-wisp, chance, we can be on the alert for it, prepare ourselves to recognize it and profit by it when it comes,” she writes:

That’s the thing about life: You can do what you do but in the end, some things remain stubbornly outside your control. You can’t calculate for dumb bad luck… My reasons for getting into poker in the first place were to better understand that line between skill and luck, to learn what I could control and what I couldn’t, and here was a strongly-worded lesson if ever there were: you can’t bluff chance.

That’s the thing about life: You can do what you do but in the end, some things remain stubbornly outside your control. You can’t calculate for dumb bad luck… My reasons for getting into poker in the first place were to better understand that line between skill and luck, to learn what I could control and what I couldn’t, and here was a strongly-worded lesson if ever there were: you can’t bluff chance.

[…]

Real life is not just about modeling the mathematically optimal decisions. It’s about discerning the hidden, the uniquely human. It’s about realizing that no amount of formal modeling will ever be able to capture the vagaries and surprises of human nature.

Dive in here.

“Do you need a prod? / Do you need a little darkness to get you going?” Mary Oliver asked in her stunning love poem to life, composed in the wake of a terrifying diagnosis. “Let me be as urgent as a knife, then, / and remind you of Keats, / so single of purpose and thinking, for a while, / he had a lifetime.”

“Do you need a prod? / Do you need a little darkness to get you going?” Mary Oliver asked in her stunning love poem to life, composed in the wake of a terrifying diagnosis. “Let me be as urgent as a knife, then, / and remind you of Keats, / so single of purpose and thinking, for a while, / he had a lifetime.”

Think of Keats when you need that prod for living — Keats, who died at the peak of his poetic powers, already having given humanity more truth and beauty in his short life than most would give if they had eternity. Or think of Bruce Lee (November 27, 1940–July 20, 1973) — another rare poet of life, who too pursued truth and beauty, if in a radically different medium; who too was slain by chance, that supreme puppeteer of the universe, at the peak of his powers; who too left a legacy that shaped the sensibility, worldview, and wakefulness to life of generations.

Bruce Lee (Photograph courtesy of the Bruce Lee Foundation archive)

On the bench across from Bruce Lee’s tombstone in Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery, where he is buried alongside his son, also chance-slain in youth, these words of tribute appear: “The key to immortality is first living a life worth remembering.” They are often misattributed to Lee himself — perhaps because of the proximity, perhaps because they radiate an elemental truth about his life. The animating ethos of that uncommon life comes newly alive in Be Water, My Friend: The Teachings of Bruce Lee (public library) by his daughter, Shannon Lee, titled after his famous metaphor for resilience — a slender, potent book twining her father’s timeless philosophies of living with her own reflections, drawn from her own courageous life of turning unfathomable loss into a path of light and quiet strength.

Get a taste with Lee’s reflections on death and what it means to be an artist of life, nested inside the little-known story of how he fought, in the final year of his life, to make Enter the Dragon what it became.

“A leaf of grass is no less than the journey work of the stars,” the young Whitman sang in one of the finest poems from Song of Myself — the aria of a self that seemed to him then, as it always seems to the young, infinite and invincible. But when a paralytic stroke felled him decades later, unpeeling his creaturely limits and his temporality, he leaned on the selfsame reverence of nature as he considered what makes life worth living:

“A leaf of grass is no less than the journey work of the stars,” the young Whitman sang in one of the finest poems from Song of Myself — the aria of a self that seemed to him then, as it always seems to the young, infinite and invincible. But when a paralytic stroke felled him decades later, unpeeling his creaturely limits and his temporality, he leaned on the selfsame reverence of nature as he considered what makes life worth living:

After you have exhausted what there is in business, politics, conviviality, love, and so on — have found that none of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear — what remains? Nature remains; to bring out from their torpid recesses, the affinities of a man or woman with the open air, the trees, fields, the changes of seasons — the sun by day and the stars of heaven by night.

After you have exhausted what there is in business, politics, conviviality, love, and so on — have found that none of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear — what remains? Nature remains; to bring out from their torpid recesses, the affinities of a man or woman with the open air, the trees, fields, the changes of seasons — the sun by day and the stars of heaven by night.

In span and in size, our human lives unfold between the scale of leaves and the scale of stars, amid a miraculous world born by myriad chance events any one of which, if ever so slightly different, could have occasioned a lifeless rocky world, or no world at all — no trees and no songbirds, no Whitman and no Nina Simone, no love poems and no love — just an Earth-sized patch of pure spacetime, cold and austere.

The moment one fathoms this, it seems nothing less than an elemental sacrilege not to go through our days — these alms from chance — in a state of perpetual ecstasy over every living thing we encounter, not to reverence every oak and every owl and every leaf of grass as a living benediction.

A century and a half after Whitman, writer Robert Macfarlane and artist Jackie Morris — two poets of nature in the vastest Baldwinian sense — compose one such living benediction in The Lost Spells (public library). A lovely companion to their first collaboration — The Lost Words, an illustrated dictionary of poetic spells reclaiming the language of nature as an inspired act of courage and resistance after the Oxford Children’s Dictionary dropped dozens of words related to the natural world — this lyrical invocation in verse and watercolor summons the spirit of the living things that make this planet a world, the creatures whose lives mark seasons and measure out epochs: the splendid “hooligan gang” of the swifts that have crossed deserts and oceans to fill the sky each spring, the ancient oak “stubbornly holding its ground” year after year, century after century.

A century after the great nature writer Henry Beston insisted that we need “a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals,” observing how “in a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear,” Macfarlane and Morris bring us the mystery and wisdom of wild things as complementary and consolatory to our tame incompleteness.

RED FOX

RED FOX

I am Red Fox — how do you see me?

A bloom of rust

at your vision’s edge,

The shadow that slips

through a hole in the hedge,

My two green eyes

in your headlights’ rush,

A scatter of feathers,

the tip of a brush.

See more here.

Sparer than Dickinson, bolder than Whitman, and absolutely singular, Lucille Clifton (June 27, 1936–February 13, 2010) has been a pillar for generations of readers and a progenitor to generations of writers. Toni Morrison found her poetry “seductive with the simplicity of an atom, which is to say highly complex, explosive underneath an apparent quietude,” poetry that “embraces dichotomy and reaches for an expression of our own ambivalent entanglements.”

Sparer than Dickinson, bolder than Whitman, and absolutely singular, Lucille Clifton (June 27, 1936–February 13, 2010) has been a pillar for generations of readers and a progenitor to generations of writers. Toni Morrison found her poetry “seductive with the simplicity of an atom, which is to say highly complex, explosive underneath an apparent quietude,” poetry that “embraces dichotomy and reaches for an expression of our own ambivalent entanglements.”

How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton (public library), curated by poet Aracelis Girmay and funded by readers via Kickstarter, collects two hundred of Clifton’s most powerful poems, from hymnal classics like “won’t you celebrate with me” to several newly discovered poems never previously published.

For a taste of these subtle seductions of atomized complexity, here is poet Terrance Hayes reading one of my favorite Lucille Clifton poems at the second annual Universe in Verse, with a charming prefatory meditation that honors her for the “literary lion” that she was and captures just how profoundly she shaped the life of literature between raising six children:

CUTTING GREENS

CUTTING GREENS

by Lucille Clifton

curling them around

i hold their bodies in obscene embrace

thinking of everything but kinship.

collards and kale

strain against each strange other

away from my kissmaking hand and

the iron bedpot.

the pot is black,

the cutting board is black,

my hand,

and just for a minute

the greens roll black under the knife,

and the kitchen twists dark on its spine

and I taste in my natural appetite

the bond of live things everywhere.

Growing up in Bulgaria, one of my most cherished objects was also one of the first fragments of American culture to enter our home after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of the Iron Curtain — a small square desk calendar in a clear plastic clamshell, containing twelve illustrated cards, each vibrantly alive with tiny black-contoured figures dancing in various jubilant formations amid a festival of primary colors. I would look up to savor its mirth between math equations and domestic disquietudes. However gloomy a day I was having, however sunken my child-heart, these figures would transport me to a buoyant world of sunlit possibility. I knew nothing about their creator beyond the name on the back of the clamshell: Keith Haring (May 4, 1958–February 16, 1990). I knew nothing about the bittersweet beauty of his courageous life, nothing about the tenacious activism behind his art, nothing about the enormous uninterrupted chain of human figures bonded in kinship, which he had painted on the remnants of the very wall whose collapse had placed this miniature monument to joy on my desk.

Growing up in Bulgaria, one of my most cherished objects was also one of the first fragments of American culture to enter our home after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of the Iron Curtain — a small square desk calendar in a clear plastic clamshell, containing twelve illustrated cards, each vibrantly alive with tiny black-contoured figures dancing in various jubilant formations amid a festival of primary colors. I would look up to savor its mirth between math equations and domestic disquietudes. However gloomy a day I was having, however sunken my child-heart, these figures would transport me to a buoyant world of sunlit possibility. I knew nothing about their creator beyond the name on the back of the clamshell: Keith Haring (May 4, 1958–February 16, 1990). I knew nothing about the bittersweet beauty of his courageous life, nothing about the tenacious activism behind his art, nothing about the enormous uninterrupted chain of human figures bonded in kinship, which he had painted on the remnants of the very wall whose collapse had placed this miniature monument to joy on my desk.

Nearly three decades later, having traded Bulgaria for Brooklyn by some improbable existential acrobatics, I encountered Haring’s work again in a magnificent mural he had painted for a young people’s club in New York City in the final year of his twenties, not long before his death, which my friends at Pioneer Works had resurrected and brought to our neighborhood. The same rush of irrepressible gladness poured into the grownup heart from the twenty-five-foot wall as had poured into the child-heart from the five-inch calendar. I grew attuned to the echoes of his sensibility bellowing down the corridor of time, reverberating strongly in the work of established artists in my own community.

Long before he moved to Brooklyn in pursuit of his own calling, poet Matthew Burgess had a parallel experience of Haring’s world-expanding art, which he first encountered on the cover of a Christmas record at fourteen, living behind the Golden Curtain of suburban Southern California as a budding artist and young gay man trying to find himself. “For those of us who grew up before the internet became ubiquitous, a bright fragment from the outer world can feel like an important discovery — and a call,” Burgess writes in the author’s note to what became his serenade to the artist who opened minds and world of possibility for so many.

A decade into teaching poetry in public schools, Burgess encountered Haring’s work afresh in a retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum. After mesmeric hours in the galleries, he wandered into the museum bookshop and went home with a copy of Haring’s published journals, which he devoured immediately. On its pages, he realized that the special native sympathy between children and Haring’s art is not an accident of his line and color but at the very center of his spirit. In an entry from July 7, 1986, Haring writes:

Children know something that most people have forgotten. Children possess a fascination with their everyday existence that is very special and would be very helpful to adults if they could learn to understand and respect it.

Children know something that most people have forgotten. Children possess a fascination with their everyday existence that is very special and would be very helpful to adults if they could learn to understand and respect it.

Having previously composed Enormous Smallness, one of my favorite books of 2015 — the wondrous picture-book biography of E.E. Cummings, another artist who so passionately believed that “it takes courage to grow up and become who you really are” — Burgess was impelled to invite young people into Keith Haring’s singular art and the large heart from which it sprang. And so Drawing on Walls: A Story of Keith Haring (public library) was born — a splendid addition to the most inspiring picture-book biographies of cultural heroes.

Burgess’s tender words, harmonized by muralist and illustrator Josh Cochran’s ebullient art, follow the young Keith from his childhood in small-town Pennsylvania, drawing at the kitchen table with his dad and dipping his little sister’s palms in paint to make her a mobile of handprints, to his improbable path to New York City.

See more here.

We might spend our lives trying to discern where we end and the rest of the world begins, but we save them by experiencing ourselves — our selves, each individual self — as “the still point of the turning world,” to borrow T.S. Eliot’s lovely phrase from one of the greatest poems ever written. And yet that point is pinned to a figment — our fundamental creaturely sense of reality is founded upon the illusion of absolute rest.

We might spend our lives trying to discern where we end and the rest of the world begins, but we save them by experiencing ourselves — our selves, each individual self — as “the still point of the turning world,” to borrow T.S. Eliot’s lovely phrase from one of the greatest poems ever written. And yet that point is pinned to a figment — our fundamental creaturely sense of reality is founded upon the illusion of absolute rest.

On March 27, 1964 — Good Friday — thousands of selves in Anchorage, Alaska came unpinned from their most elemental certitudes about reality, about safety, about the thousand small sanities by which we bestill this turning world to make it livable.

At 5:36PM, as the afternoon sun was slipping lazily toward the horizon — that quiet daily assurance that the Earth moves intact on its steady axis along its unfaltering orbital path — street lights began swaying, then flying. The pavement beneath them accordioned, then gaped open, swallowing cars and spitting them back up. Walls came unseamed and reseamed before disbelieving eyes that had not yet computed, for it was beyond the computational power of everyday consciousness, what was taking place.

Photograph by Genie Chance, taken immediately after the earthquake hit. (Courtesy of Jan Blankenship — her daughter — and Jon Mooallem.)

Buildings rippled “up and down in sections, just like a caterpillar,” in one observer’s recollection, before ripping apart and crumbling completely like the brittle simulacra of safety that buildings are. Inside them, books toppled from their shelves to take rapid turns levitating from the floor, flames engulfed school science labs as chemicals crumpled together, and cast-iron pots of moose stew jumped off kitchen stoves.

The city’s electric grid was snapped and uprooted — in the below-freezing cold, in the descending dusk, all power went out.

Photograph by Genie Chance, taken immediately after the earthquake hit. (Courtesy Jan Blankenship and Jon Mooallem.)

When people tried running for their lives, they found their basic biped function furloughed — the Earth hurled each step back at them, tossing their center of gravity like a marble around a child’s cupped hand.

Water levels jumped as far away as South Africa. I picture my grandparents’ well in Bulgaria undulating in the middle of the night as they slept heavily under their Rhodope wool blankets, having celebrated my mother’s second birthday in the hours before Anchorage came unborn.

At 9.2 on the Richter Scale, the earthquake was more powerful than any previously measured — so violent that, as one seismologist phrased it, “it made the earth ring like a bell.” Just as the collision of two black holes ripples the fabric of spacetime with such brutality that it rings a gravitational wave, two tectonic plates had been in slow-motion collision for millennia, building up pressure that finally, on that early-spring afternoon, rang the planet itself and discomposed Anchorage into a level of trauma that would devastate the community, then jolt it into discovering its own entirely unfathomed wellsprings of resilience, solidarity, and generosity.

Driving to the local bookstore with one of her three children was a woman who would emerge as the unlikely hero not only of the community’s survival but of its transformation through tragedy. As their world fell apart, she would magnetize people into falling together.

Genie Chance with dahlias, Alaska. (Courtesy Jan Blankenship and Jon Mooallem.)

Genie Chance (January 24, 1927–May 17, 1998) is the protagonist of Jon Mooallem’s uncommonly wonderful book This Is Chance!: The Shaking of an All-American City, A Voice That Held It Together (public library). Driving the heart of this scrupulously researched and sensitively told story about a singular event at a particular time in a particular place is the timeless, universal pulse-beat of assurance, suddenly rendered timely to the point of prophetic — the assurance that comes from the lived record of communities surviving cataclysms even more savaging than our own and emerging from them stronger, more closely knit, more human.

Read more here.

“Praised be the fathomless universe, for life and joy, and for objects and knowledge curious,” Whitman wrote as he stood discomposed and delirious before a universe filled with “forms, qualities, lives, humanity, language, thoughts, the ones known, and the ones unknown, the ones on the stars, the stars themselves, some shaped, others unshaped.” And yet the central animating force of our species, the wellspring of our joy and curiosity, the restlessness that gave us Whitman and Wheeler, Keats and Curie, is the very fathoming of this fathomless universe — an impulse itself a marvel in light of our own improbability. Somehow, we went from bacteria to Bach; somehow, we learned to make fire and music and mathematics. And here we are now, walking wildernesses of mossy feelings and brambled thoughts beneath an overstory of one hundred trillion synapses, coruscating with the ultimate question: What is all this?

“Praised be the fathomless universe, for life and joy, and for objects and knowledge curious,” Whitman wrote as he stood discomposed and delirious before a universe filled with “forms, qualities, lives, humanity, language, thoughts, the ones known, and the ones unknown, the ones on the stars, the stars themselves, some shaped, others unshaped.” And yet the central animating force of our species, the wellspring of our joy and curiosity, the restlessness that gave us Whitman and Wheeler, Keats and Curie, is the very fathoming of this fathomless universe — an impulse itself a marvel in light of our own improbability. Somehow, we went from bacteria to Bach; somehow, we learned to make fire and music and mathematics. And here we are now, walking wildernesses of mossy feelings and brambled thoughts beneath an overstory of one hundred trillion synapses, coruscating with the ultimate question: What is all this?

That is what physicist and mathematician Brian Greene explores with great elegance of thought and poetic sensibility in Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe (public library). Nearly two centuries after the word scientist was coined for the Scottish mathematician Mary Somerville when her unexampled book On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences brought together the separate disciplinary streams of scientific inquiry into a single river of knowledge, Greene draws on his own field, various other sciences, and no small measure of philosophy and literature to examine what we know about the nature of reality, what we suspect about the nature of knowledge, and how these converge to shine a sidewise gleam on our own nature. With resolute scientific rigor and uncommon sensitivity to the poetic syncopations of physical reality, he takes on the questions that bellow through the bone cave atop our shoulders, the cave against whose walls Plato flickered his timeless thought experiment probing the most abiding puzzle: How are we ever sure of reality? — a question that turns the mind into a Rube Goldberg machine of other questions: Why is there something rather than nothing? How did life emerge? What is consciousness? What is the most important fact of the universe?

Brian Greene

Although science is Greene’s raw material in this fathoming — its histories, its theories, its triumphs, its blind spots — he emerges, as one inevitably does in contemplating these colossal questions, a testament to Einstein’s conviction that “every true theorist is a kind of tamed metaphysicist.” Looking back on how he first grew enchanted with what he calls “the romance of mathematics” and its seductive promise to unveil the timeless laws of nature, he writes:

Creativity constrained by logic and a set of axioms dictates how ideas can be manipulated and combined to reveal unshakable truths.

Creativity constrained by logic and a set of axioms dictates how ideas can be manipulated and combined to reveal unshakable truths.

[…]

The appeal of a law of nature might be its timeless quality. But what drives us to seek the timeless, to search for qualities that may last forever? Perhaps it all comes from our singular awareness that we are anything but timeless, that our lives are anything but forever.

[…]

We emerge from laws that, as far as we can tell, are timeless, and yet we exist for the briefest moment of time. We are guided by laws that operate without concern for destination, and yet we constantly ask ourselves where we are headed. We are shaped by laws that seem not to require an underlying rationale, and yet we persistently seek meaning and purpose.

Dive in here.

One of the most bewildering things about life is how ever-shifting the inner weather systems are, yet how wholly each storm consumes us when it comes, how completely suffering not only darkens the inner firmament but dims the prospective imagination itself, so that we cease being able to imagine the return of the light. But the light does return to lift the darkness and restore the world’s color — as in nature, so in the subset of it that is human nature. “We forget that nature itself is one vast miracle transcending the reality of night and nothingness,” Loren Eiseley wrote in one of the greatest essays ever written. “We forget that each one of us in his personal life repeats that miracle.”

One of the most bewildering things about life is how ever-shifting the inner weather systems are, yet how wholly each storm consumes us when it comes, how completely suffering not only darkens the inner firmament but dims the prospective imagination itself, so that we cease being able to imagine the return of the light. But the light does return to lift the darkness and restore the world’s color — as in nature, so in the subset of it that is human nature. “We forget that nature itself is one vast miracle transcending the reality of night and nothingness,” Loren Eiseley wrote in one of the greatest essays ever written. “We forget that each one of us in his personal life repeats that miracle.”

We forget, too, just how much of life’s miraculousness resides in the latitude of the spectrum of experience and our dance across it, how much of life’s vibrancy radiates from the contrast between the various hues, between the darkness and the light. There is, after all, something eminently uninteresting about a perpetually blue sky. Van Gogh knew this when he contemplated “the drama of a storm in nature, the drama of sorrow in life” as essential fuel for art and life. Coleridge knew it as he huddled in a hollow to behold “the power and ‘eternal link’ of energy” in his transcendent encounter with a violent storm.

The life-affirming splendor of the spectrum within and without is what Japanese poet and picture-book author Hiroshi Osada and artist Ryoji Arai celebrate in Every Color of Light: A Book about the Sky (public library), translated by David Boyd — a tender serenade to the elements that unspools into a lullaby, inviting ecstatic wakefulness to the fulness of life, inviting a serene surrender to slumber.

Born in Fukushima just as World War II was breaking out, Osada composed this spare, lyrical book upon turning eighty, having lived through unimaginable storms. I can’t help but read it in consonance with Pico Iyer’s soulful meditation on autumn light and finding beauty in impermanence, drawn from his many years in Japan. Arai’s almost synesthetic art — radiating more than color, radiating sound, a kind of buzzing aliveness — only amplifies this sense of consolation in the drama of the elements, this sense of change as a portal not to terror but to transcendent serenity.

See more here.

“Some dreams aren’t dreams at all, just another angle of physical reality,” Patti Smith wrote in Year of the Monkey, one of my favorite books of 2019 — her exquisite dreamlike book-length prose poem about mending the broken realities of life, a meditation drawn from dreams that are “much more than dreams, as if originating from the dawn of mind.”

“Some dreams aren’t dreams at all, just another angle of physical reality,” Patti Smith wrote in Year of the Monkey, one of my favorite books of 2019 — her exquisite dreamlike book-length prose poem about mending the broken realities of life, a meditation drawn from dreams that are “much more than dreams, as if originating from the dawn of mind.”

As I leaf enchanted through The Unwinding (public library) by the English artist and writer Jackie Morris, this quiet masterpiece dawns on me as the pictorial counterpart to Smith’s — a small, miraculous book that belongs, and beckons you to find your own belonging, in the “Library of Lost Dreams and Half-Imagined Things.”

Its consummately painted pages sing echoes of Virginia Woolf — “Life is a dream. ‘Tis waking that kills us. He who robs us of our dreams robs us of our life.” — and whisper an invitation to unwind the tensions of waking life, to follow a mysterious woman and great white all-knowing bear — two creatures bound in absolute trust and absolute love — as they hunt for wild dreams, “dreams that hold the scent of deep green moss, lichen, the place where the roots of a tree enter the earth, old stone, the dust of a moth’s wings.”

What emerges is a love story, a hope story, a story out of time, out of stricture, out of the narrow artificial bounds by which we try to contain the wild wonderland of reality because we are too frightened to live wonder-stricken.

While a spare, poetic story accompanies each pictorial sequence, partway between fairy tale and magical realism, the text is only a contour around one of myriad possible shapes and shadings each watercolor dreamscape invites — each years in the painting, each a consummate Rorschach test for the poetic imagination that confers upon our waking hours the iridescent shimmer that makes life worth living.

In the twelfth dreamscape, titled “Truth: The Dreams of Bears,” the enchanting woman whispers into the soft warm ear of the sleeping bear:

If I said that my love for you was

If I said that my love for you was

like the spaces between the notes of a wren’s song,

would you understand?

Would you perceive my love to be, therefore,

hardly present, almost nothing?

Or would you feel how my love is wrapped

around by the richest, the wildest song?

And, if I said my love for you is like

the time when the nightingale is absent

from our twilight world,

would you hear it as a silence? Nothing?

No love?

Or as anticipation

of that rich current of music,

which fills heart,

soul,

body,

mind?

And, if I said my love for

you is like the hare’s breath,

would you feel it to be transient?

So slight a thing?

Or would you see it as life-giving?

Wild?

A thing that fills the blood, and

sets the hare running?

See more here.

RECOLLECTIONS OF MY NONEXISTENCE

|

“I am convinced that most people do not grow up,” Maya Angelou wrote in her stirring letter to the daughter she never had. “We carry accumulation of years in our bodies and on our faces, but generally our real selves, the children inside, are still innocent and shy as magnolias.” In that same cultural season, from a college commencement stage, Toni Morrison told an orchard of human saplings that “true adulthood is a difficult beauty, an intensely hard won glory.”

“I am convinced that most people do not grow up,” Maya Angelou wrote in her stirring letter to the daughter she never had. “We carry accumulation of years in our bodies and on our faces, but generally our real selves, the children inside, are still innocent and shy as magnolias.” In that same cultural season, from a college commencement stage, Toni Morrison told an orchard of human saplings that “true adulthood is a difficult beauty, an intensely hard won glory.”

It is tempting, for it is flattering, to think of ourselves as trees — as firmly rooted and resolutely upward bound; as creatures destined, in Mary Oliver’s lovely words, “to go easy, to be filled with light, and to shine.” But even if the highest compliment a great poet can pay a great woman is to celebrate her as a human tree, we are not trees — we don’t branch and root from a single point, we don’t grow linearly; we disbark ourselves at will, at the flash and flutter of a heart, self-grafting every love and loss we live through; our growth-rings are often ungirdled by self-doubt, by regress, by the fits and starts by which we become who and what we are: fragmentary but indivisible. The difficulty of growing up, the hard-won glory of it, lies in the self-tessellation.

Art by Arthur Rackham for a rare 1917 edition of the Brothers Grimm fairy tales. (Available as a print.)

That is what Rebecca Solnit explores in a passage from Recollections of My Nonexistence (public library) — her splendid memoir of longings and determinations, of resistances and revolutions, personal and political, illuminating the kiln in which one of the boldest, most original minds of our time was annealed.

Three quarters into the book and half a lifetime into her becoming, Solnit writes:

Growing up, we say, as though we were trees, as though altitude was all that there was to be gained, but so much of the process is growing whole as the fragments are gathered, the patterns found. Human infants are born with craniums made up of four plates that have not yet knit together into a solid dome so that their heads can compress to fit through the birth canal, so that the brain within can then expand. The seams of these plates are intricate, like fingers interlaced, like the meander of arctic rivers across tundra.

Growing up, we say, as though we were trees, as though altitude was all that there was to be gained, but so much of the process is growing whole as the fragments are gathered, the patterns found. Human infants are born with craniums made up of four plates that have not yet knit together into a solid dome so that their heads can compress to fit through the birth canal, so that the brain within can then expand. The seams of these plates are intricate, like fingers interlaced, like the meander of arctic rivers across tundra.

The skull quadruples in size in the first few years, and if the bones knit together too soon, they restrict the growth of the brain; and if they don’t knit at all the brain remains unprotected. Open enough to grow and closed enough to hold together is what a life must also be. We collage ourselves into being, finding the pieces of a worldview and people to love and reasons to live and then integrate them into a whole, a life consistent with its beliefs and desires, at least if we’re lucky.

Hello Reader! This is a special annual edition of the

Hello Reader! This is a special annual edition of the

Talking to yourself can be useful. And writing means being overheard.

Talking to yourself can be useful. And writing means being overheard.