In June 2020, I entered an audio room in Clubhouse where a man on stage, humming and half-singing, asked fellow speakers to help ID the music stuck in his head. With each incorrect guess, he grew more frantic, encouraging audience members to come on stage and keep the hunches coming. Eventually, in a burst of elation, they discovered the lost song. I don’t remember the title or the artist––it was both anticlimactic and unimportant––but the collective energy of the room was infectious.

A conversation would start with people pontificating on the purpose of life, then swing to alien conspiracies and the possibility of reptoids on earth. With rooms unnamed and ephemeral, you wouldn't know what everyone was talking about until you entered and couldn’t know what was discussed if you hadn’t. It was an audio-only Omegle with a slick mobile UI and the off-chance of encountering Oprah Winfrey or John Mayer.

Ten months later, what was once an experimental beta is now a full-fledged social media platform that has raised funds at a rumored $4 billion dollar valuation. A little over a year old, with 10 million weekly active users, Clubhouse has hit escape velocity— growing pains notwithstanding. Attempts to capitalize on Clubhouse are changing the conversation.

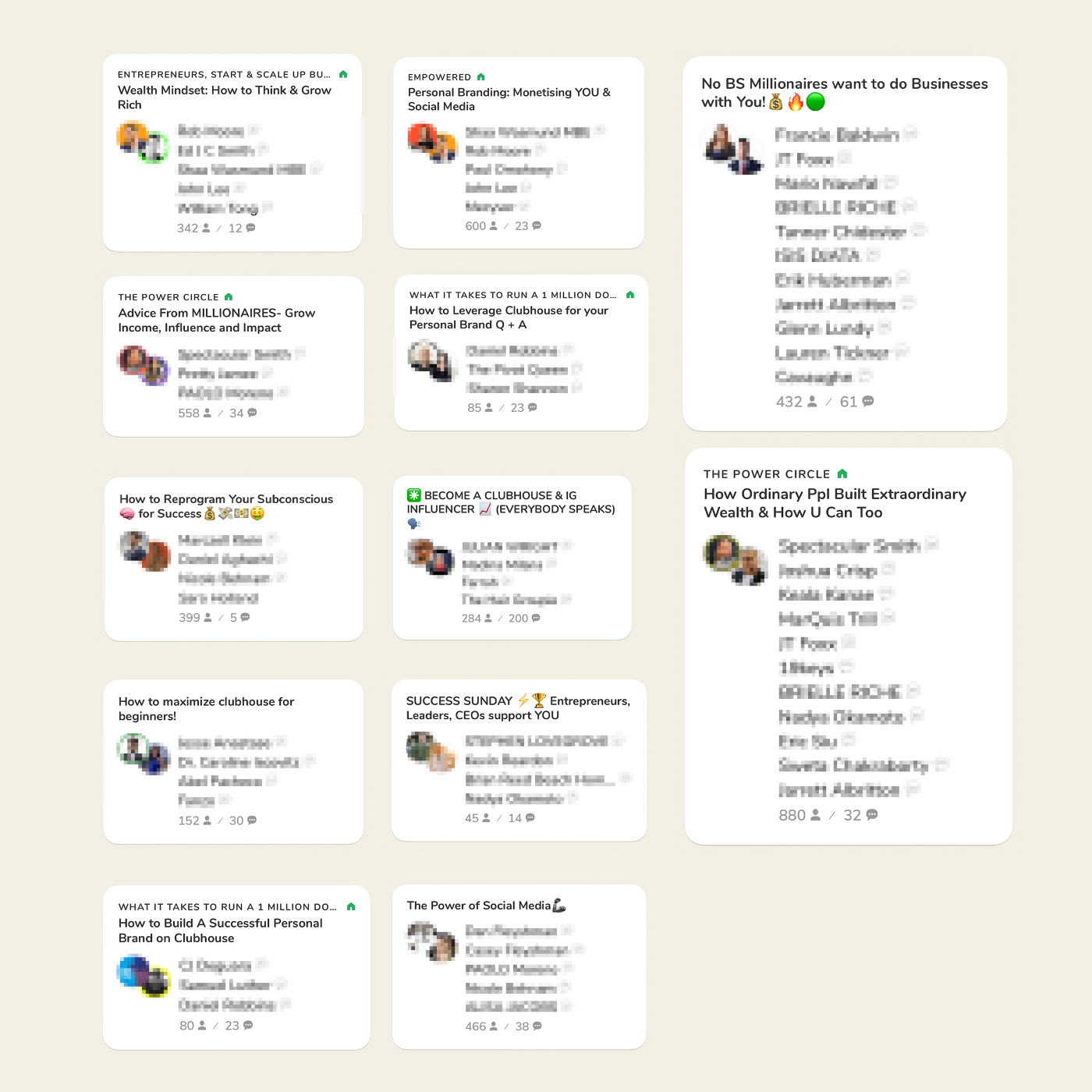

The breakout success of the app has given rise to a growing subset of users who want to cash in on what Clubhouse can offer. As the app seeks out a strategy to monetize conversations, its users are already commoditizing themselves. Self-proclaimed wealth coaches host discussions on the gilded path to financial prosperity. A stream of rooms converse on leaving your 9-5, building your personal brand, and, of course, becoming a Clubhouse influencer. Companies, seeing the value of a new marketing channel, host rooms that feel more like comms than conversation.

Early on, the app felt different: fresh, surprising, and out of the ordinary. As speakers step on the stage increasingly as panelists and podcasters, instead of just people, Clubhouse might become a series of live podcast recordings, brand-friendly conversations, and marketing disguised as discussion. Users cashing in on Clubhouse comes at a cost: the novelty that attracted people initially might be fading into formality.

Early Ephemeral Days

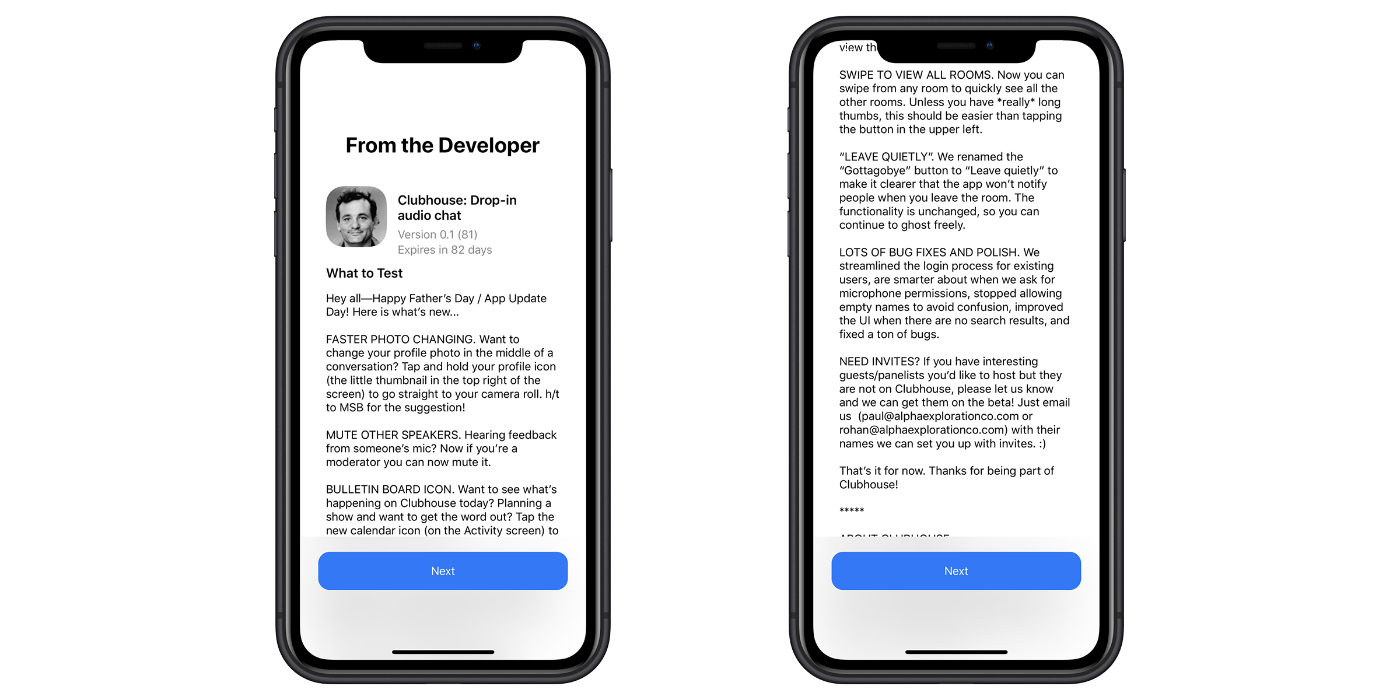

If a perfect storm is the uncanny combination of unfortunate events, the arrival of Clubhouse was the perfect calm. The Test Flight beta of the iOS audio app emerged in March 2020, at the start of the pandemic, a reprieve from calendars overloaded by Zoom happy hours and virtual birthday parties. We craved connection, but had grown tired of scheduling and ceremony. Clubhouse was the informal answer to the question of conversation.

The initial iteration of the app was a single unnamed room hosting conversations between tech early adopters. I joined in June after breathless reviews of the app and screenshots featuring its early logo––a young smirking Bill Murray––reached my corner of Twitter. Exclusive invites were a social currency at the time, but I joined the waitlist on a Saturday night and was in by Sunday morning.

Clubhouse co-founders Paul Davidson and Rohan Seth described the potential and promise of the app:

“Clubhouse is voice-only, and we think voice is a very special medium. With no camera on, you don’t have to worry about eye contact, what you’re wearing, or where you are. You can talk on Clubhouse while you’re folding laundry, breastfeeding, commuting, working on your couch in the basement, or going for a run...It’s a place to meet with friends and with new people around the world—to tell stories, ask questions, debate, learn, and have impromptu conversations on thousands of different topics.”

Prominent tech personalities known for sticking close to scripts spoke unedited and unencumbered, providing glimpses into their politics or sharing their current reading lists. At Friday listening parties, coinciding with album release day, speakers gathered to hear the latest tracks, then vacillated between cutting critique and speaking sentimentally. In “Clubhouse After Dark,” conversations stretched from the evening into the early hours of the morning, with speakers divulging dating stories on Tinder matches gone wrong and pandemic pairings. FOMO may have driven early sign-ups, but users stayed for the conversations, sharing their weekly Screen Time report showing Clubhouse in the lead.

Siri Srinivas, a Principal at Draper Associates, was an early Clubhouse user, spending north of 4-5 hours per day on the app when she joined in early June:

"The early days of Clubhouse were heady and exciting. It was a new model for community and for socializing. People were extremely welcoming to new users. You'd see tech luminaries casually hanging out in rooms. There were around 2,000 odd people on the platform when I joined, and it was intimate and easy to meet fantastic people. In some ways, early Clubhouse felt a lot like early Twitter to me. I've been on Twitter since 2008, and it's always felt like Twitter allowed you to listen to extremely insightful people talk to each other, and Clubhouse, similarly, let you eavesdrop and participate in great conversations between interesting people. And like Twitter, Clubhouse too allowed for plenty of frivolous fun, especially in a year when we've needed it."

There’s a well-known Clubhouse rule: the longer a room is open, the probability of discussing Clubhouse approaches one. Regardless of whether the conversation was a contentious back-and-forth on politics or more casual fare on the merits of unschooling your kids, it’s common for people to quip, “...and that’s the magic of Clubhouse!”

The sentiment is one-part cultish and one-part cringe, but expressed a certain truth. Voice embeds a particular intimacy into conversations among strangers––whether you’re talking or listening. Socializing with strangers from around the world felt novel; Clubhouse didn’t invent social audio, but they certainly introduced its magic to the masses.

Part of that mysticism was the impermanence of conversations. Discussions in the app were inaccessible to users after they occurred, and recording rooms was considered prohibited. Observing the rules of Las Vegas, what happened in Clubhouse stayed in Clubhouse. Conversations vanishing as quickly as they were conjured added allure to the app. A Clubhouse notification was an invitation to take part in the ephemeral. Much of social media has come to mean polished posts and immaculate images. Platforms that reject permanence free users from the expectation (or the ability) to edit. Ephemerality allows for a greater level of imperfection, and thus authenticity. Ignoring a Clubhouse notification meant missing a real conversation happening now and only now.

Early into the life of the app, an anonymous “Overheard on Clubhouse” Twitter account began broadcasting speaker quotes to their timeline. To some, it felt like a breach of trust. Users speculated online about the identity of the account holder, recommended removing the person from the app, and noted they would no longer be “relatively unfiltered” on the app. Despite brief discussions on how to prevent this behaviour on Clubhouse, users quickly resigned to the fact that the app would change: “I don’t like it, but seems like the reality is that this is going to happen.”

It was the start of what was to come.

Conversations, once content to be casual, were crowded out by the discussions set on “finding an audience.” One-off chats became less frequent, making way for regularly recurring audio and lecture series. Scheduled conversations, once rare and documented in a sparse Notion document linked within the app, were replaced by a full-fledged calendar feature to find rooms hosted around the clock––from “Personal Branding & Marketing on Clubhouse” to “Next Level Business for Life Coaches.” Entering an unplanned room felt like serendipitous discovery, but planned and purposeful discussions often feel like the work of sitting in a webinar. A particular professionalization of the app took hold as people saw the opportunities that stepping on stage might secure, leaving intimate conversations to flee from the app or hide in discreet corners, increasingly harder to find.

Hustlers are Here

Clubhouse is full of filthy rich people and they want you to be filthy rich too. At least that’s the impression you might get today scrolling through the running rooms.

From wealth masterminds to the secrets of the 1%, speakers promise listeners advice on achieving financial greatness. If you listen in, you’ll hear quick quips and anecdotes of the self-actualized on what it takes to get to the top:

“Milliseconds are the difference between a medal and going home with your head down.”

“Think and grow rich? True. Think about it. But you better move your feet.”

“Never stop until you get what you want. Then, keep going until you get what’s next.”

Listen even closer, beyond speakers quoting Bruce Lee and Arnold Schwarzenegger, and the truth reveals itself: the speakers probably aren’t millionaires. Their bustling business is selling the dream of owning your own business, an MLM-esque maneuver as old as time retro-fit for our new audio age.

If business counsel isn’t the topic of conversation, it’s mental state coaching. After all, unlocking the answer to anything is a matter of mindset. Well, mindset and marketing. In one room, a self-proclaimed master marketer encourages an author to build a community before releasing her book and provides inexact advice on implementing an upsell strategy. In another room, a woman counsels listeners on the path to making $30K a month on Clubhouse without ads; a red dot emoji at the end of a room name indicates that the room was being recorded. In another room drawing to a close, alleged entrepreneurs ask audience members to “follow the mods” and “check out their socials.” If you heed their advice, clicking through to their Clubhouse bios, you’ll find descriptions that read like the headlines of Taboola ads:

“I help job seekers GET NOTICED & Control Financial Fears of JOB LOSS”

“5 Million Followers | Featured in Forbes | Listed on Stock Exchange”

“From Zero to $43 million Launching Consumer Products to market”

Once a destination that felt like the back room of a bar, the audio app has become another epicenter of hustle culture.

Clubhouse suggests that the list of rooms you see is small compared to the true number of rooms happening all at once around the world. If you’re not seeing the rooms you like, follow more people to see something new. Yet, masterminds on money, mindset, and marketing seem to be overrepresented. The observation that hustle rooms loom large on Clubhouse is far from unique:

Conversations are increasingly less about understanding and intimacy and more about amplification and influence. There are, after all, millions of active users, and just as many to sell coaching, courses, ebooks, and masterminds to. The undercurrent of commerce impacts conversation. Speakers introduce themselves with superlatives, citing awards and credentials. On an app where conversation already ran the risk of being performative, speakers now perform willingly for the crowd.

Once nameless rooms now have titles and descriptions that set the trajectory of conversation. Speakers swinging with abandon from disjointed subjects, letting conversations unfold organically, now keep discussions bound and focused. Room moderators, indicated by a green badge under their avatar, act as conversation czars suggesting people speak in turns based on the order of the queue, limiting talk time to 60 seconds per person. Every so often, a moderator “resets the room”—returning to the topic at hand or summarizing the chat so far for newcomers, breaking the flow of conversation. Discussions that once disappeared are now multi-streamed, recorded, uploaded, and tweet-threaded for good measure.

Creators are Coming

Beyond the rooms whispering supposed secrets of the wealthy, there’s a crop of audio creators making their mark on Clubhouse. Community builders, comedians, and conversationalists alike are running daily or weekly rooms, armed with talking points and impressive guests. Rather than one-off conversations that disappear, they’re creating serialized productions.

The Good Time Show, hosted by Aarthi Ramamurthy and Sriram Krishnan, has had Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Marques Brownlee (MKBHD) grace their audio stage. What began as a casual nightly show between spouses and their friends in tech has spawned into a media juggernaut with exclusive access to impressive guests, a professionally designed website, and an official Twitter page where clips from the show are regularly uploaded. Full recordings of episodes have been uploaded by others to YouTube. Other notable shows include Big Ideas with regular hosts Antonio García Martínez, Katherine Boyle, Erik Torenberg, and Marc Andreessen. They’ve hosted Sam Harris, Tyler Cowen, and Agnes Callard.

In a rare move for a social media platform, Clubhouse’s co-founders have publicly and repeatedly said they’ll avoid an ad-based monetization model. Instead, their path to revenue will more than likely involve building tools to help creators build bigger audiences. Speculative predictions include taking a cut of paid rooms or boosted rooms or subscriptions with exclusive features for creators.

For speakers and club owners who have managed to cultivate the art of conversation, Clubhouse has taken notice. In December 2020, it was reported that the app was building an invite-only “Creator Pilot Program.” One invited member revealed that the program was in its infancy and he had not yet been compensated. In March 2021, the company launched “Clubhouse Creator First,” their first accelerator for creators with the goal to “help support and equip emerging creators with the resources they need to bring their ideas and creativity to life.” On March 28, 2021, during a Clubhouse Town Hall, a weekly update on Sundays hosted by the co-founders for the community, Paul Davidson revealed that those accepted would receive $5,000 per month if accepted into the program.

Then, on April 5, the app introduced Clubhouse Payments, allowing tipping for a select group of creators, expanding the pool soon after. Clubhouse currently takes 0% of tips. Davidson has encouraged room hosts to seek out sponsors and suggested brands get in touch with the company directly. In comparison to other social apps, this could be a welcome model that puts money in the pockets of platform content creators.

Creators who want to take a different route to monetizing their rooms are courting brand partnerships. On March 28, 2021, a Passover Seder room hosted by the Hot on the Mic Club created by Leah Lamarr featured Tasty, a cooking brand offshoot of Buzzfeed, on stage. When a now popular “shoot your shot” show, “NYU Girls Roasting Tech Guys,” emerged on the app, venture capitalists were quick to point out the sponsorship potential of the show. According to The Hustle, brands like Recess and Starface have since sponsored the show, and the hosts have been approached with investment offers. On April 27, it was announced that the creators behind the show had signed with WME, a prominent talent agency.

Clubhouse doesn’t just want to mint celebrities, they’re courting existing ones too. Zendaya and Sam Levinson spoke on Clubhouse about their most recent project, the Netflix film Malcolm & Marie. Bill Gates was interviewed on the app by journalist Andrew Ross Sorkin, talking about his new book How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, a conversation that was polished and PR-friendly. Demi Lovoto, on an ongoing press tour, stopped by Clubhouse to discuss her forthcoming documentary, Dancing With the Devil. Her manager, Scooter Braun, was virtually seated next to her in the room discussing the process of bringing the project to life.

These serialized productions, sponsored rooms, and straight-laced interviews can provide an interesting listening experience, but feel more like under-polished podcasts than spontaneous conversations. It’s not uncommon for Clubhouse rooms to serve as live recordings with the Clubhouse version disappearing, but a living version uploaded online as a podcast. There was a point where you might feel compelled to stay up late for certain conversations. Now, with someone likely to upload it, you have the option to listen later. The official Clubhouse Twitter account now uses the hashtag #OverheardOnClubhouse.

Hunting For Hidden Conversations

Every social platform starts off by getting us to play. You hang out with friends and tinker with features. Prior to becoming a stream of professional photos from influencers and advertisements from brands, Instagram provided a place for sharing egregiously edited moments with friends. Before the copyright lawyers flocked to YouTube, the platform was the Wild West, where you could watch full episodes of television shows and home-made videos with copyrighted music.

Much is said about how platforms change and adapt in an effort to monetize. Less is said about how users bend to monetize themselves––their knowledge, looks, connections, cunningness––and how that changes the platform too. With critical mass comes the opportunity and then the urge to capitalize. Whether it’s the nature of increasingly precarious employment or the simpler drive to become what we see, there’s a discontent with 9-to-5—at some point, everyone wants to “scam their way out of a desk job.” The horror that kids want to be influencers instead of astronauts seems misplaced when it’s adults who want the same. We’re all champing at the bit to become creators, entrepreneurs, makers. These platforms often help make those dreams a reality, providing the promise of a crowd: people to influence, to build for, to sell to.

Varying degrees of marketers, sellers, and hucksters have a stronghold on Clubhouse. But corners of the app remain eclectic. Clubhouse is at its best when conversations are surprising, weird, intimate—and they still can be.

On November 27, 2020, users gathered in a room entitled “Is Kevin Hart Funny??” to discuss whether the comedian was a humourless sellout. Hart, allegedly an investor in Clubhouse, hopped on stage to face his detractors in a room surpassing 3,500 people.

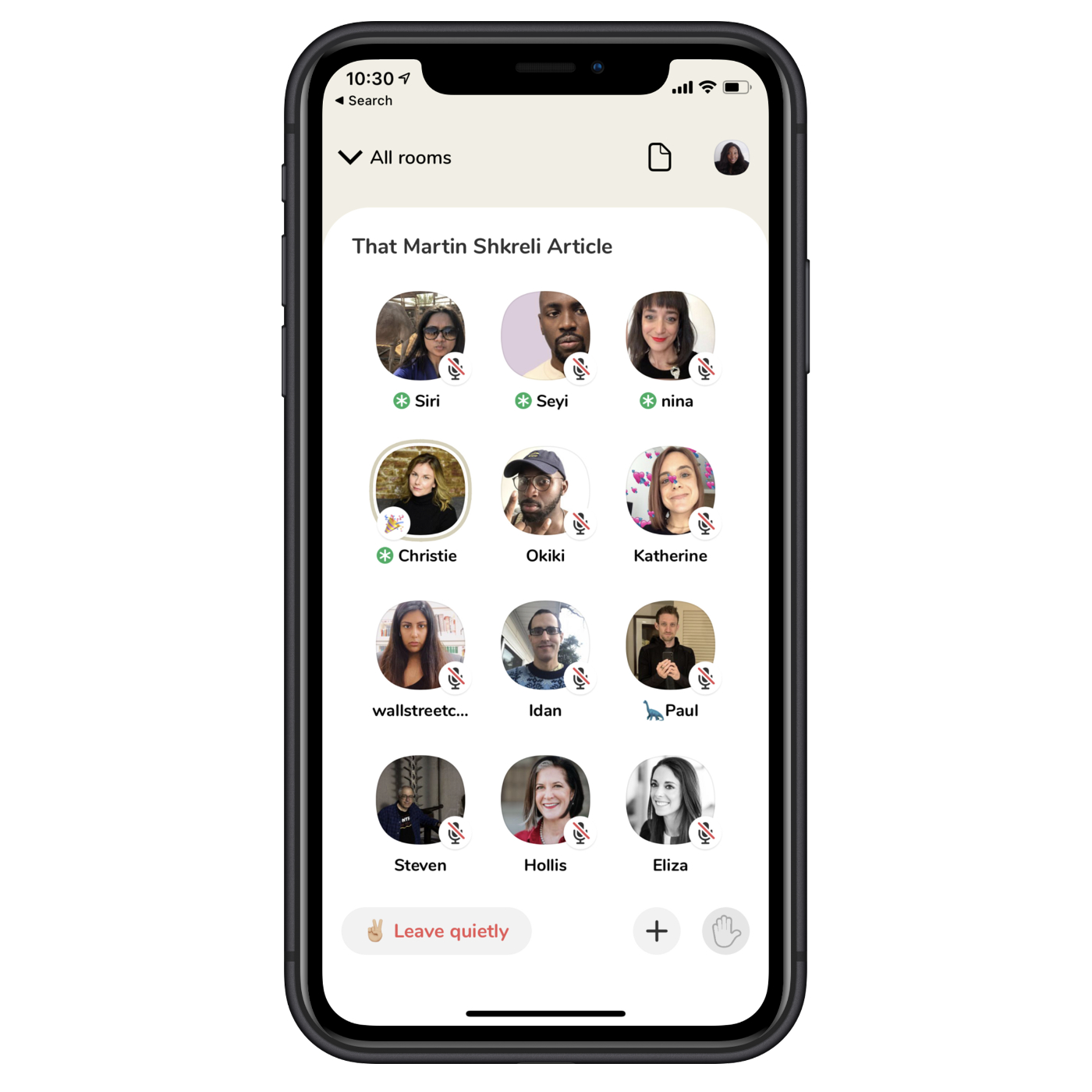

When an article from Elle about the journalist Christie Smythe and her relationship with Martin Shkreli went viral, she joined a Clubhouse room to candidly discuss the article and her relationship with the infamous pharmaceutical executive currently serving seven years for securities fraud, elaborating on the smell of microwaved hot wings from the prison canteen.

Srinivas, a former journalist and interview buff, fielded questions for Smythe and kept conversation going in what became a charged room:

“I never expected it to blow up the way it did. I started the room because I wanted to talk about the Elle piece with a few of my Clubhouse friends, who I've discussed pop culture and news with several times. The room quickly ballooned as more people weighed in. Somebody listening in felt like it wasn't fair to talk about Christie without her being in the room (I don't agree with this assessment. It was a news article, and fair game); so he invited her to Clubhouse. And she joined! The Elle article was one of those fine Internet moments when everybody is talking about one thing. That she walked into the Clubhouse room a few hours after the story came out created the perfect storm—it is exactly the kind of magic Clubhouse is built for. To her credit, she was very open to fielding questions and talking about a very sensitive matter, and it made for a great conversation.”

Once, a group gathered to discuss the rampant crime in San Francisco and what could be done, in part laying blame on the city’s district attorney, Chesa Boudin. Unplanned, he accepted an invitation onto the room’s stage, hot-headed and filled with contempt for his critics. He quickly reverted to polite politics, staying for over an hour to discuss his department’s role in the city. Depending on whom you ask, one of two things happened on that stage: Boudin galloped away gallant and victorious, convincing the crowd of the nuance of the criminal justice system or was annihilated on stage, unconvincingly deflecting responsibility for rising home break-ins and the city’s laissez-faire approach with repeat offenders.

Once, I stumbled across a room of people attempting to break the world record for the largest group of people simultaneously showering, the sound of water faucets competing for airtime.

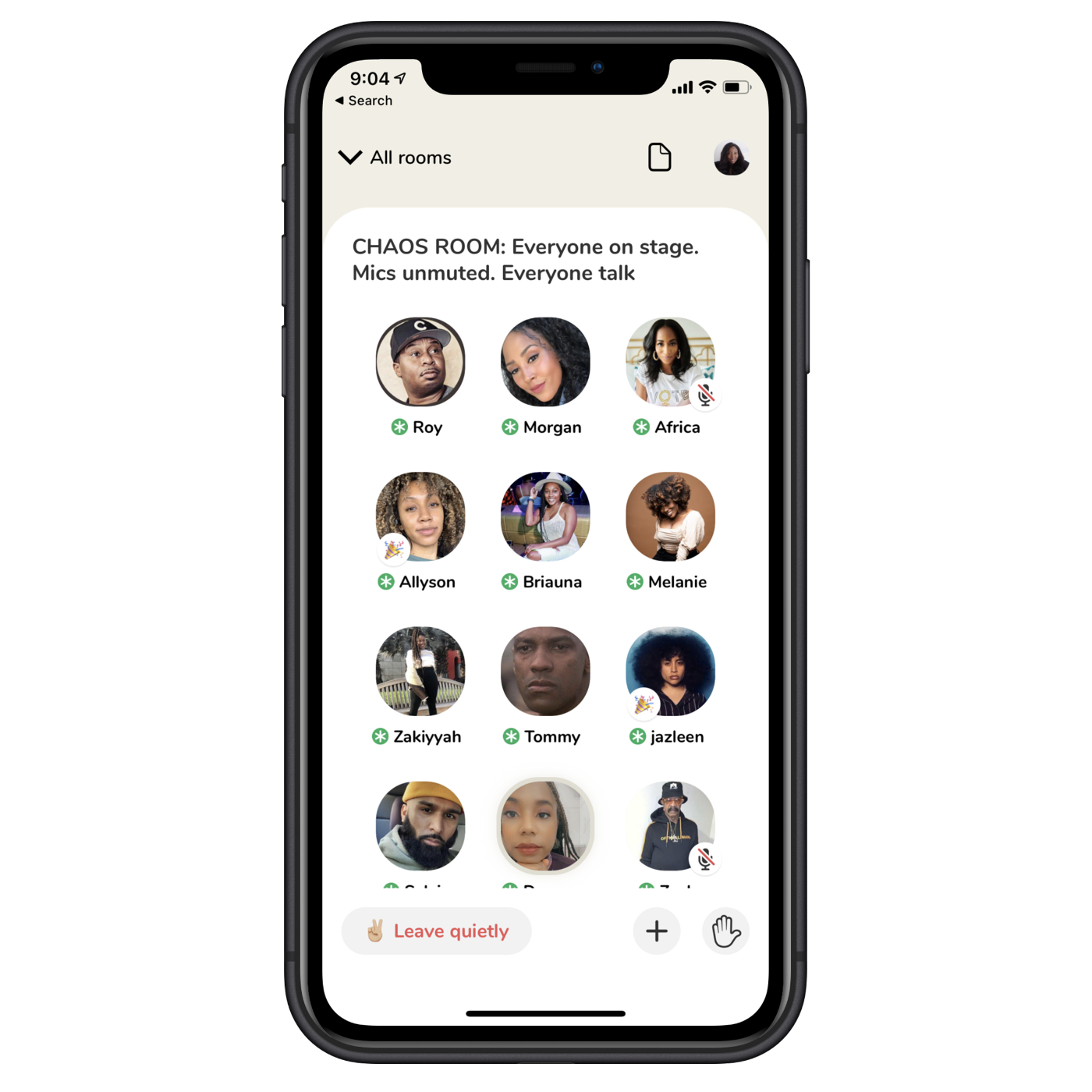

Another time, I entered a room hosted by Roy Wood Jr., a comedian and correspondent on The Daily Show, where the title was perfectly apt: “CHAOS ROOM: Everyone on stage. Mics unmuted. Everyone talk.” I laughed out loud at the sheer silliness of what sounded like (and probably was) hundreds of people speaking in unison.

I asked him recently what it was like to host that particular room:

“[It] was fun. The idea for it came from just seeing other rooms on Clubhouse with just too many people on stage at the same time. And it just becomes so hectic that the conversation can't be productive. So the idea was, what if there's a room where the purpose of the room is an unproductive conversation? It sounded like a good idea at the time. For me, it was about having a space where you could parody the ridiculousness that is some of the rooms on Clubhouse.”

Wood, a fan of Clubhouse from the beginning, no longer hosts rooms on the app:

“I was very impressed. It seemed like a place to have some really good curated conversations. But in the bigger scheme of things, I did not find Clubhouse to be the most advantageous place to always have conducive conversations...Comedians are back out, the country's opening up. So it's interesting to see how Clubhouse has shifted now that people are on the go again.”

He still listens to Clubhouse from time to time, citing one of his favorite recurring conversations as one where spouses of incarcerated individuals meet to talk.

“I found that to be one of the more interesting rooms in terms of people helping people, and just hearing some of the horrors of the criminal justice system.”

Putting aside the shocking and the chaotic, it might be the intimate rooms on Clubhouse that are the best of all. One day, a Holocaust survivor came on stage to share their story. On the night that Chadwick Boseman died, multiple rooms mourned his passing and told tales that spoke to his character. In another room about Steve Jobs, early Apple employees and friends gathered to discuss him not as a legend, but as a human.

Great conversations still exist, they’re just increasingly hard to find. Perhaps it’s more of a people problem than a platform one––after all, most conversations are boring. And of course, great creators deserve to make a living off their craft. But it’s worth wondering what cashing in does for collective conversation.

Finding offbeat and interesting spaces on the internet is a game of whack-a-mole. Each new social network feels fresh at first, until the veneer of cool starts to peel a way, only to be replaced by a bevy of self-made entrepreneurs, marketers, and brands hard-set on turning conversation into content marketing. It happened to MySpace, it happened to Facebook, and it’s happening to Clubhouse. Enjoying Clubhouse necessitates pushing your way through the champagne crowd at a conference convention, wandering into the back rooms to talk with the people at coat check about art and God.

On an app filled with millions of users, human passion and ingenuity always exist and are captured in conversation. Maybe the relative rareness of those rooms is what will actually keep them special as the app evolves. Pockets of magic remain on Clubhouse, you just have to sift through all the noise to find them.

This piece was edited by Rachel Jepsen.