TL;DR

- This article is for someone trying to decide whether to work at an early-stage, venture-backed startup.

- There is a romantic vision of startup employment that doesn’t hold up under close scrutiny.

- Business model risk is extreme and the financial opportunity cost is significant.

- Typically we assume that a startup is a better overall employment experience, this probably isn’t true for most people

- There are some circumstances where working at a startup makes sense! But it is important to go in with open eyes.

If you work in Silicon Valley for long enough, you will have your own near-miss story. This is when, through unfortunate circumstance or innate stupidity, you reject or ignore a startup opportunity that would have paid off big. We all have them. I blew off Allbirds in early 2017 (who needs more ugly sneakers? Turns out everybody, apparently). My editor Nathan did some freelance work for Coinbase in their first year, never really followed up (whoops), and asked to be paid in USD (double whoops).

Equity comp and being mission-driven are the startup world’s ideological red pill. The lionized riches of founders and early employees who celebrated their IPOs with ice sculptures and yachts, combined with cool words like “matched incentives” and “mission-driven culture” make an equity-based offer pretty hard to ignore. Join a startup and change your life.

The basic proposition is this: “we raised a lot of venture capital and plan on becoming an enormous company. Join us, take a haircut on salary, but earn way more in the future in the form of equity.”

Today, I stand before you to deliver a consummate contrarian message, rarely seen or heard of in these parts:

You probably shouldn’t work for a startup.

This is the napkin math for the masses, the people who, through no fault of their own, believe that joining a startup isn’t a huge mistake.

There are a few select cases where startup employment makes sense! But they are so rare, and it’s so easy to fool yourself into thinking a bad opportunity is a good one, that I recommend extreme levels of caution before signing anything that’ll bind you to a fledgling company’s fate.

Before we dive in—I am obviously a hypocrite. I am currently working at a SaaS startup and write this newsletter via a media startup. My hands are dirty, too, with that sickly sweet VC money, as I have advised VC funds on potential investments in the past, and still do. In acknowledgement that I am an active participant in the industry I am going to take a tough stance on today, my goal is to allow you, my readers, a clear-eyed view of the tradeoffs of startup employment.

And you'll see what I learned from my own experiences in startups and how I plan to evaluate opportunities going forward.

So let’s explore the trade-offs and separate the myth from the reality—first, by exploring the financial returns of working at a startup, then, looking at the emotional ones.

Business model? Where we’re going, we don’t need a business model

When I first started learning about technology companies in college, someone showed me a video of Elon Musk buying a one-million-dollar McClaren supercar after selling his first company. The clip is a classic of startup lore. He states that three years prior he was “sleeping on the office floor,” and now here he is buying one of the world’s most luxurious vehicles.

This kind of clip is part of the startup world’s foundational mythology: all you have to do is find a startup, hope the founder is “just crazy enough to make it work,” and your millionaire dreams will come true.

While I desperately want this to be the reality, truly obscene wealth is typically only available to the first ~10 employees of a company that exits (via IPO or acquisition) at a valuation of $1B or more—a so-called unicorn company. Rather than being treated as rare phenomenal outliers, these unicorn companies are a necessity for venture capital funds to be successful. So when a startup takes those venture dollars, they are almost always going for a big exit, or they’ll be pressured by their investors to hyper-growth their way toward one. Extreme risk, extreme reward.

So how can you think about the financial rewards as an early startup employee? The big risk you are taking on is “will this thing actually work?”

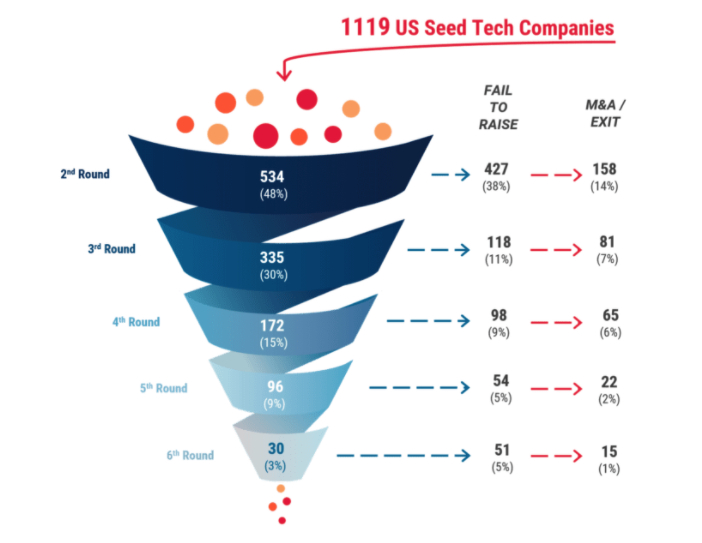

The answer is usually hell no. The best data set I could find pegged unicorns at ~1% of venture-backed startups. Of the initial group of 1,119 seed-stage tech startups in the U.S., only twelve made it to unicorn status.

Note: This data set is from the 2009/10 vintage. You need this long to determine success because startups can take 10+ years to have their outcomes come to pass. I would guess that this total volume has increased (while the unicorn percentage stays the same) but only because of hugely increased private sector capital amounts. But if you have data saying this is better now send it my way! Prove me wrong.

Keep in mind this unicorn outcome percentage (less than 5%) is from investors who have more knowledge than you, make their living picking startups to bet on, and typically get to make about 20 different startup investments every 2-3 years. You, on the other hand, only get one shot at a time. So if you want to pick a winner, you’d better be a damn good picker. Much better than your average VC.

You’ll sometimes hear an argument, “well I can pick better than a VC, this industry is my domain expertise.” Unfortunately for this argument, domain expert VCs exist! Their win rate is fairly similar to the generalist VCs. It is incredibly difficult to pick a winning startup and you are unlikely to be better at it than a full-time professional.

This is by far the biggest risk in startups. Almost all venture-backed startups don’t have a successful financial outcome. Why this matters to you as a person evaluating employment with these types of companies, is that they will typically offer you far less cash than other offers with the idea that the equity you have the option to own will be worth millions someday.

Equity is percentage ownership in the business (more precisely, equity compensation in early-stage startups is typically an option to eventually purchase some ownership in the company). By making you an “owner” early on, you are told that you will become a millionaire. Recommended equity and compensation for a seed-stage company (data from Index Ventures) ranges from .05%-1%. While this may sound appealing, it isn’t as good as it sounds.

Let’s assume the most magical of scenarios. You are a senior engineer who joins the next hot startup and receives 1% ownership in the company as part of your compensation. After you get hired, the company stops taking venture funding and doesn’t hire any more employees, so your 1% remains undiluted. After four years, you’ve vested all your equity and the startup gets acquired for $1B! You now own 1% of a billion dollars—your equity is worth $10M.

Note: It never happens like this.

Now, $10M is a flabbergasting amount of wealth. But even if all the other necessary conditions for this math to work out are met, you’re still operating on a 2% business model success rate! If you add in the way below market rate salaries, subpar seed-stage healthcare benefits, and no 401k, the opportunity cost + financial downside is severe.

Notes: There are a whole bunch of detailed equity mechanics that we don’t have time for today. These introduce additional layers of risk even beyond the whole business model thing! Option pool size, ratchets, taxes, top-offs, single and double triggers, and other lawerly terms. All of these things can have a major impact on your personal economic outcomes but we just don’t have the space for. For brevity, we are focused on startup risk. Just know there are other more nuanced things that add complexity that Napkin Math will address at a later date.

Don’t believe me? Let’s do an expected value calculation (yes this math is rough, there is a reason this newsletter is called Napkin Math!). Say you have a 2% chance of picking a unicorn and being a member of the founding team. That 2% is honestly way too high for most people, and perhaps a bit low for others, but a good median to anchor on. $10M * 2% = $200K. And realistically you’re only going to get that this tranche of equity every 3-4 years at most, so that’s a risk-adjusted value of $50–$66k.

In contrast, if you were to take a job at a tier 1 tech firm, such as Facebook or Google, as a high-quality engineer your salary can be $200-400k with an additional $100-250K in equity. You will receive the best benefits package known to mankind, with massages, free food, the finest gear money can buy, 401Ks, bonus programs, copious amounts of vacation, and the list goes on. Your total compensation package of salary + equity + benefits will be far higher versus a startup.

The question you have to ask, do I think it is more likely that this startup will be worth a billion dollars (2% chance)? Or is it more likely that Google, Facebook, Amazon, or Apple, will still be around (100% chance)?

In the long-term, risk-adjusted view, taking a job at a startup is a bad financial choice.

Note: This is assuming that you can get a job at one of these fancy companies! Which is a big assumption. But in my opinion, if you are talented enough to make a marked difference at an early stage company you are talented enough for these companies. Whether people can penetrate the sometimes discriminatory nature of these company’s hiring process is another issue, but let’s hope that this is something that is improved.

Startups aren’t always a great place to work.

So we talked about how startups usually aren’t as lucrative as they seem. But that’s not the only reason people join them. There’s also the idea that it’s going to be more fun and more fulfilling than working as a boring corporate stiff. There are two components to this: mission and experience.

MISSION

From the ages of 19-21, I spent my time as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, popularly known as the Mormon church. I worked 12 hours a day for two years straight with only Christmas and Mother’s Day off. During that time, people tried to stab me, passersby in the street screamed in my face, and I helped people get through some of the worst life has to offer (disease, drugs, abuse, and other crises). For this job, I was paid a total of 0 dollars. In fact, I used money that I had saved since I was 11 to pay for it myself. It was the best and worst and best again experience of my life; it shaped everything about me.

So you will have to forgive me if I laugh when people say their company is “mission-driven.” As someone who was literally a missionary, a startup selling productivity software is a business, not a calling.

In startup dogma, you are told to “hire missionaries, not mercenaries.” These mythical employees will put it all on the line. They will sacrifice and devote themselves to whatever cause your business is proclaiming as its divine mandate. Hiring these employees is good advice! As a founder, I would also want employees who believe so passionately in what I’m doing that they would take reduced wages and work longer hours. Perhaps it is my inner Marxist, but I can’t help but view businesses proclaiming to be mission-driven to actually be fueled by ideological exploitation.

Now, you can argue that many businesses do aspire to world-changing higher causes: SpaceX will make us interplanetary! The Every Bundle will ensure writers are compensated fairly! Shopify will help SMBs fight Amazon! And that’s sometimes very true. Venture dollars were the initial fuel for innovations that have been literal lifelines during the pandemic—Zoom and Moderna’s vaccine. But forgive me if I am by default skeptical here. These startups are beneficial to society as a side-effect of their true purpose.

Unlike an actual missionary, startups are not reporting to God. But they are beholden to beings who believe themselves equally worthy of worship: venture capital investors. When push comes to shove, the legal structure of all capitalist entities is to maximize shareholder wealth. Startups are only pursuing a non-wealth returning cause as long as the majority of shareholders say they are. Employees (aka the missionaries) never own the majority. When you inject capital that demands billion-dollar returns, the divine text shifts from the mission statement to the term sheet.

This theme of recruiting zealots permeates startup land. You have to have depressed wages to reduce cash burn. Employees are encouraged to work incredibly hard because the world is competitive and building stuff from scratch is hard! Founders want to win, employees want to win, and the best they’ve come up with is a culture of more hours = better outcomes. You have a better chance of winning if smart people offer up their personal lives as a blood sacrifice to the great gods of 3x cash on cash returns.

Again, let’s put this in contrast to working at a big tech company. I have more friends than I have toes or fingers that work 20 hours a week at Google and make twice what I do. Note: There are many folks who work hard, long hours there. But these rest and vest jobs very much exist alongside those people grinding. While there are undoubtedly still believers in “the cause” at these types of companies, most people are very aware that the business exists to make money and destroy competitors. And the truth is, all venture-backed startups exist for the same reasons, no matter what the mission statement says. Working at a company that isn’t depending on its employees sacrificing themselves to its “greater good,” and where employees don’t have to deal with the existential threat of their company always being on the edge of failure, strong work/life boundaries are much more possible.

Experience

Of course, the feeling of fulfillment that comes from the pursuit of a holy mission is not the only reason to work at a startup. The additional attraction of startups is that living in one is supposed to make you the resident of a land of builders. There is lots to like about the projects you get at a startup! You’ll have a huge breadth and touch all the business in some way. Doing this is challenging, fun, and rewarding.

At a big company you will not have the same amount of breadth, but the scale is unbelievable. A few years ago, I went to church in Bentonville, Arkansas, home of Walmart corporate headquarters. There I met a 28-year-old who told me he managed dog food for the company. Startup guy that I am, my initial reaction was an eye roll. Dogfood? How trite. It was only later that I learned that he was managing over $2 billion dollars worth of revenue before he hit the age of 30. That is something no startup can ever provide. Yes, startups give you breadth, but big companies give you scale. Don’t knock it till you try it.

The final assertion of startups is that working for one means you won’t have to deal with internal company politics. Startups are where scrappy young folks come together to build awesome products, not waste time convincing the suits what’s worth working on! In my experience, this is never true. Startups are just as political, but rather than the voting bloc consisting of various cross-functional stakeholders, it is instead an electoral committee of one: the founder. Startup politics are about making the founder like/respect you enough so they will give you permission to get things done. The question you have to ask yourself is: would you rather appease one person who has barely any check on their power OR a group of individuals who need to be aligned on the same objective?

A startup’s work environment can be better for you if you are entirely bought in on the mission, are comfortable spending less time on yourself/family/friends, and want to learn quickly and work to gain experience across departments. But big companies will likely give you better work/life balance, way more resources, and unbelievable scale. While I would never tell an individual what to do, most people would be happier with the latter option.

Startups are probably getting better to work at

Startupland is changing. In my last few years, I have seen founders say and do things that I never would’ve imagined them doing five years ago. There are now options outside of the historical norm of hard-nosed, hardcore environments. Here’s some stuff to consider when deciding whether the opportunity cost of joining a startup makes sense for you:

- Work at a startup that explicitly says you will work 45 hours a week: As wild as that may sound, there are now startups out there that believe this. Note: I could be a masochist and to everyone else working less than 65 hours a week is normal. I recently started working in the Utah tech scene for the first time and was flabbergasted to see the parking lots empty by 5:30. Because of local culture, family is considered more important than employment (how novel!) and work/life balance is paramount. I’ve never worked 45 hours in my life before now and let me tell you, it is amazing. I see the sunrise! I see the sunset! I have time to write overly long explainers of financial concepts! This extra time allows me to devote to other activities that give personal alpha.

- Remote remote remote remote: Remote work being normalized at startups allows for more flexibility than ever before. Remote allows you to only work exactly as much as you need to be successful and not one iota more. Without a boss over your shoulder you are measured via outcome rather than face time. Remote also allows you to work in lower cost areas. A startup wage as a senior engineer in San Francisco is barely enough to cover rent. In Ohio, I believe that level of income automatically makes you a land baron. Remote work allows you to do geographical arbitrage and make lower salaries work. This is also true for big tech jobs! You can do those remotely now too.

- It feels like a calling: Maybe you really do believe that a startup you are considering is performing a higher task for humanity. You feel genuine, almost religious zeal for the cause. If you can picture yourself doing nothing else, go for it! Just know that you are likely consigning yourself to elevated stress and poor financial outcomes. But if you are ok and even excited despite that tradeoff because the business will make a difference about a cause you care about, you should do the job.

- You come from a nontraditional no-background: It can be very tough to get a job at Facebook (especially at the start of your career). Startups are a great way into the industry simply because most of the time they can’t be picky. They can’t afford the proven, credentialed talent so they have no choice but to take a chance on someone who shows potential. Startups can act as the entry point by which non-Ivy League folks can break in.

My current situation in startups fulfills scenarios 1, 2, & 4. Working in Utah tech gives me work-life balance. Plus remote work allows me to keep my costs lower (especially relative to SF) and gives me time to invest in my writing. I also was a sociology major with a 3.4 GPA and went to a good not great school. You put this all together and I am in that narrow set of circumstances that it makes sense.

The conditions for success in startups are so, so rare, but hopefully this guide will allow you to go in with clear eyes as to what the tradeoffs are. If you have any questions or would like to discuss an offer you’re considering, DM me on Twitter. If you would like more numerical breakdowns of topics involving finance, tech, or startups, subscribe below. Your first month is only a dollar and your support means I am able to continue to publish these types of resources.

-e