This is a free preview of a subscribers-only post.

TL;DR

- Finance increasingly feels broken, but don’t panic, this has happened before

- From the ancient Sumerians to Venetian Traders to American Railroad Tycoons, each of these periods of huge technological/organizational change forced an improvement in finance

- Net Income is one of the results of these changes and helps illustrate why it matters

- The Income Statement has slowly lost its utility and is no longer as accurate as it was when it was first broadly popularized

- We are having the first Napkin Math sponsor (ever!). Let me know what you think of having an ad. (If you are on the paid list you will never receive an ad).

This week’s newsletter is sponsored by MasterWorks—a leading platform for buying and selling shares in iconic artwork. You can read more about how I use them (and why I just bought a Basquiat worth $20mm) at the bottom of this post. But if you’re curious, Napkin Math readers can skip their 17,500 person waitlist:

I failed my first finance class. Watching an old, bespectacled professor illustrate income statement formulas on a dusty chalkboard, I just couldn’t bring myself to care. It was dry, it was boring, and it was especially dull in comparison with my burgeoning interest in technology. At night in my college bedroom (a literal closet with 6 foot ceilings that only had room for a bed far too small) I was reading in Techcrunch about how the world was being changed by startups. What did I care for the stuff of spreadsheets? People were building an entirely new economy online! Income was boring, users were cool. Note: It did not occur to me to ask how these startups were making money. As I said, I failed the class.

While I don’t remember much from my second attempt at the class (necessary for graduation) there was one sentence that has lingered over the years. My professor defined finance as “the art and science of managing money.” Science because finance was a predictable, rules-based universe and art because there was no universal agreement on how the rules actually worked. They were *waves hands* up for interpretation. This sentiment always felt a little off to me.

My earliest dissolution with ASS thinking (Arts and ScienceS) was after college, as I reviewed financial models for VCs and helped startups prepare their pitch decks. When an investor was compelled by a narrative or if the entrepreneur “fit the mold” of a winner, magically the art of the numbers always made the model work. A startup’s financial projections always had them attacking a $10B market they were sure to win. If you want to just invest in someone you consider exceptional or if you think the business fits a thematic trend, then just say that! It was this willful self-deception, the idea that the narrative magically manifested itself in the numbers, that really got my alarm bells ringing. It is self-delusion to warp the numbers to fit the outcome you were already hoping for. Note: Somehow the winner archetype was always a white guy who went to Stanford.

Watching these two camps of believers proselytize their gospel to each other — parishioners in the faith of finance — I became more and more convinced that there was something going wrong. By allowing ourselves to accept a contradictory financial duality, by making finance science when it suited us, art when it did not, the purpose of the system broke. Financial forecasts, whose intent was namely that, to forecast the future, were instead the last, non-determinative steps used to justify millions of dollars of investments. Instead of relying on financial statements to determine business history or future trajectory, investors/startups were reliant on metrics not all present in those documents.

Ultimately, the line connecting current monetary reality with a reasonable, risk-adjusted future has been stretched past its original design. This breakdown goes far beyond startup valuations. It is in the mania of AMC, of the tech bubble of 2000. It is of us caring more about the Q&A section of an analyst call than the actual financial results. If you are paying attention, there are little tendrils of intellectual decay everywhere in finance. Perhaps you have felt this too, but overall, our system just feels a little off.

While this shift feels scary, it is important to point out that every major piece of financial innovation was the result of exactly times like this. The pattern is always the same: new technology enables new kinds/scales of businesses to exist that surpass our current financial conventions’ ability to understand them, so we invent new financial conventions that make sense of the new kinds of businesses.

The Precedents

Sumerian ledgers

In 8000 B.C. (about 4000 years before they invented writing) the Sumeraians needed to keep track of the goods they were trading. Up to this point, it had been person to person trades. You give me a goat, I’ll give you 3 chickens, that sort of thing. However, with increased scales of production and new shipping technologies like barges, they needed some way to record who owed what to whom as they shipped goods up the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. To solve this complexity, they invented the Bulla.

These were clay balls that, on the inside, held clay tokens that represented grain or animal stocks. Bullas were used to hold multiple tokens together to help prevent dishonesty. Honestly, they invented a fairly ingenious system, “In order to account for the tokens, the bulla would have to be crushed to reveal their content. Seals were impressed into the opening of the bullae to prevent tampering. Each party had its own unique seal to identify them. Seals would not only identify individuals, but it would also identify their office. Sometimes, the token was impressed onto the wet bulla before it dried so that the owner could remember what exactly was in the bulla without having to break it.”

Probably superior to the chaos of counting chickens on your fingers!

Fast forward a few thousand years (and skipping the invention of currency, writing, and arithmetic) and the system was in a major crisis yet again.

Venetian accounting

By the 1400s, technological progress around maritime technology had enabled global trade to dramatically scale the size of businesses and the complexity of the goods/services they provided. Large merchant ships were capable of traversing the continents and required multi-year investments financed by large trading families. Note: I am not using family in the sense that startups use it. This was literally blood brothers running shipping routes around the horn of Africa. Previous systems of bookkeeping just weren’t keeping up. The variety in trading goods, the length of the enterprise, all of these variables had surpassed the capability of previous methods of bookkeeping. Merchants were never totally sure of how their business was doing.

The Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli, a collaborator of Leonardo DiVinci, popularized a novel method of accounting called “Double-Entry” with the publish of his 1494 work entitled “Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioi et Proportionalita.” In it (and in his works that followed) he, in the painfully boring detail that would become the hallmark of the profession he was inventing, laid down the foundational processes for accounting. Journals, ledgers, year-end closing dates, trial balances, cost accounting, accounting ethics, the Rule of 72, all from my man Luca. Again, finance was able to respond to technology’s demands and innovate.

Industrial cash flow

Another 400 years and another technology/business evolution pushed finance to its limits. The railroads and steel producers of the Industrial Revolution created businesses that had a larger scale, complexity, and capital requirements than ever before. There had been earlier iterations of the financial statement, but none had properly settled the relationships between cash, income, and debit/credit. That changed in 1863, when a factory manager for the Dowlais Factory Company tried to figure out why his books showed profit but he had no cash to buy factory equipment. How could they have a profit but no money? Confusion, chaos, even in the supposedly modern age of steel.

His attempts to answer the question of cash availability, codified in a letter to his superiors, were the origins of the modern relationship between the income statement and the cash flow statement. He didn’t know it, but he was joining in a great debate, thousands of years in the making, simply asking, what is a profit?

Note: Delightfully, early iterations of the income statement had whatever the analysts deemed important. In Wells Fargo’s earliest documents they had an expense line called “Robberies.” Billy the Kid is part of the history of our financial system. Note within a note: It was incredibly difficult to find sources on this topic (I bought 3 textbooks off of Amazon just for this one piece) so please appreciate the hundreds of pages of reading that went into this little anecdote.

Net Income’s Definition and Origin

In previous pieces in this series, we have established the foundations of the income statement. Revenue, COGS, Gross Margin, on and on. The original goal of the income statement is right there in the name - to tell you how much money you made! Revenue is the money that comes in and essentially, everything that comes underneath that is to tell you how many costs to weigh against that revenue. The end result of this algorithm is Net Income. Net Income is the profit that results from Revenue - COGS - Operating Expenses - All Other Expenses.

The origins of this term’s definition are in the industrial age scenario I described above. This is the last time our intellectual framework for finance was updated. There have been improvements in how corporations report their finances, but the 3 financial statements were birthed in the 1800s. They were designed for manufacturing businesses, not for the new models enabled by today’s technology. Net Income doesn’t always fit modern business realities.

The complications and implications of our system’s failure

If I have had one point I have tried to drive home throughout this income statement series, it is just how malleable public financial documents are (let alone the wacky world of startup finances). All of my pieces have been takes or interpretations that might feel radical but were just offshoot strains of this financial chaos. MoviePass incorrectly interpreted their COGS as a marketing expense and damned themselves. WeWork’s community-adjusted EBITDA was merely an unorthodox offshoot of the big branch of finance and wasn’t necessarily so evil after all. I also espoused the heretical idea that businesses should probably do their best to never pay a penny in taxes.

When you look at a net income line, you need to know that what was shown was a choice, not a result. Management teams will do everything in their power to make sure that the income statement (and net income by extension) will tell the story that they want it to. This temptation, to be storyteller rather than truthsayer, is so strong that financial statement management can easily lead to illicit or fraudulent activity. See Enron, Greensill, Katerra, etc.

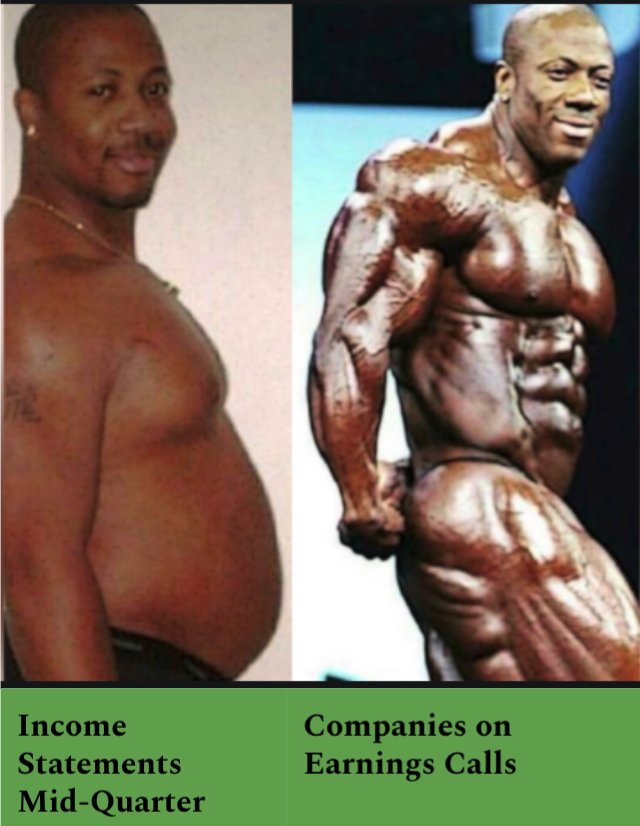

It is equally important to know that financial statements are bred in social progress. When you are new to the game of finance, you will usually enter with the assumption that you can hold these documents to be accurate representations of reality. I think of them like a bodybuilding competition. When they pose on stage (in earnings calls or board meetings) they are in tip-top shape. The lighting is just right and they’ve been on a water fast for 2 days. They look incredible. In the offseason however...

This is the same human being, Shawn Roden, a Mr. Olympia Champion in 2018.

Financial statements are the same. While they may be “true” that does not mean they have the whole truth. They are manipulations, performances, prepared for a certain moment.

This is especially accurate in the technology-infused businesses of today. The documents that are legally required of them (the income statement, the cash flow statement, and the balance sheet) had their last major invention during the industrial era. The measures that are most predictive of business success are simply not in them. If I were trying to compare SaaS companies to invest in, I would not pay anything beyond cursory attention to COGS, but I would want to know a lot about their Net Dollar Retention. This is not available in financial documents. If I were trying to analyze an e-commerce business, I would want to know their CAC/LTV ratio. This is not available in financial documents. I can do this for just about every industry that wasn’t already around in the 1800s.

This is at least part of the reason why the system feels wobbly today. The metrics that indicate a business's success aren’t contained in the financial statements. The old standards aren’t all that useful anymore, but non-standardized measures of performance lead to chaos. A good investor can sort the signal from the noise, but now we are at the point where everything could be a signal. You can essentially rationalize any poor financial choice.

Note: In my opinion, part of the reason so many hedge funds and public investors have pushed into private investing is because the information arbitrage advantage is incredibly strong. You can go to a private company, get data that you would never get from a public company, and be able to more accurately price an asset than a public investor.

For operators and investors, this means that you likely have to move beyond standard financial metrics as you evaluate projects. There are other, perhaps more accurate, measures to use.

Now that we have wrapped up this series on the income statement stretch, our next explainer series will focus on these more esoteric metrics. We will cover marketing funnels, sales performance metrics, and perhaps even more intricate things like Black Scholes models.

Thank you to the thousands of people who have joined since we started this series two months ago. I promise you this next act is going to be even better than the last. If you want to join us, hit the subscribe button below.

Note: I am taking next week off for my first real vacation in over a year. I’ll be back the following week with new products, even spicier takes, and even better content just for you. Thank you for being patient and supporting my rest as a creator.

My new hedge against inflation

I don’t mean to brag, but Napkin Math has been going well. So well, in fact, that I am now the proud investor in a Basquiat valued at over $20M. How did I make such an expensive purchase on the back of this humble newsletter? After all, growth has been good. But it hasn’t been that good.

The answer is MasterWorks. Their service allows both accredited and non-accredited investors to buy shares in a painting. Think artists you would brag to your friends about at a dinner party, like Picasso, Warhol, and of course Basquiat. The best part is I feel fancy (and will hopefully make a great return).

There is good evidence that could happen since art prices crushed S&P returns by 174% since 1995.

Masterworks is a truly unique service that I can't recommend enough. As a special bonus, I'm partnering with Masterworks to let Napkin Math readers skip their 17,500+ person waitlist :)