Hi, Nathan here! Have you ever wondered why the paid newsletter model is so much more popular for non-fiction than fiction? Kinda strange, given that fiction has a long and proud tradition of serialized content, and fiction book sales typically are equal to or larger than non-fiction book sales. Today we have a superb guest essay by Elle Griffin that dives into the reasons why, and asks whether things might change soon. Elle is a fiction writer herself, with a gothic novel coming out on her Substack soon. I hope you enjoy this as much as I did!

Ok, enough intro! Here’s Elle.

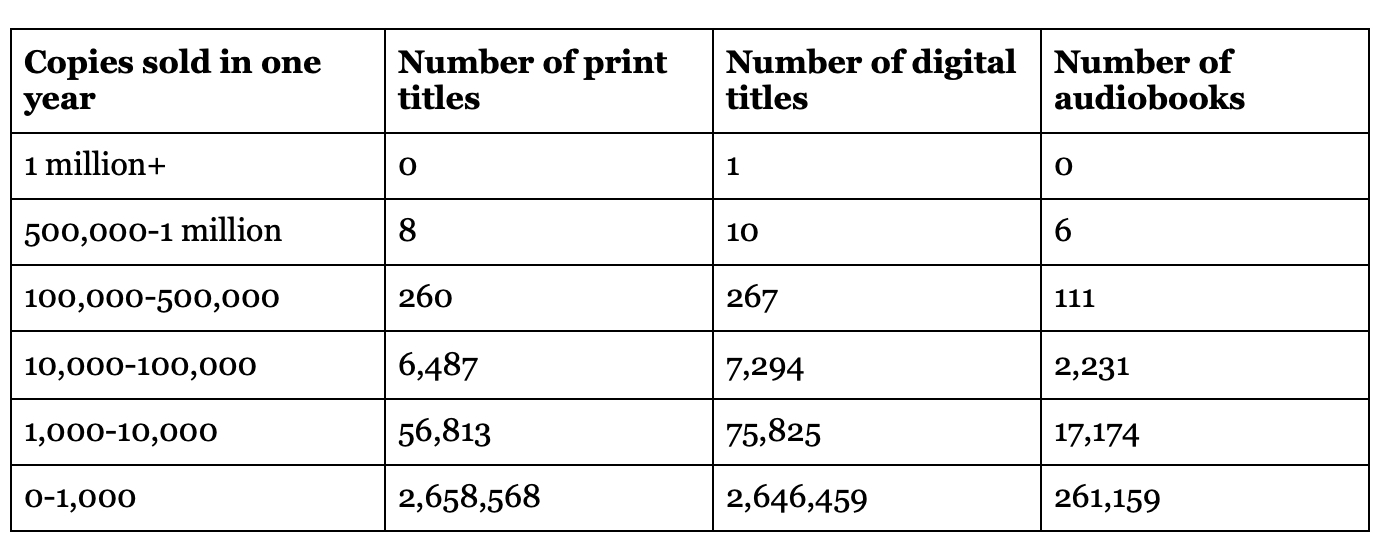

In an article about pandemic book sales, The New York Times disclosed recently that “98 percent of the books that publishers released in 2020 sold fewer than 5,000 copies.” And according to Bookstat, a website that aggregates data around book sales, of the 2.7M books sold online in 2020, only 268 sold more than 100,000 copies—that’s 0.01 percent of books.

Meanwhile, 96 percent of those 2.7M sold between 0 and 1,000 copies.

*According to 2020 online sales from Bookstat

On the high end, 11 books sold more than 500,000 copies last year—the 10 best-performing Netflix films last year saw more than 68M views in their first month. If even our best-selling books hit only a fraction of the audiences of best-performing films, then books as a medium have a very niche audience indeed.

The vast majority of published authors can’t eke out a living on that kind of niche appeal. The “Big Five” publishing houses—soon to be the “Big Four” as Penguin Random House announced the acquisition of Simon and Schuster—make money the same way venture capital investors do. They provide seed investments (called “advances”) of between $5-15K for first-time authors (much more for successful authors), to thousands of authors a year. There is no expectation that each of those authors will sell much of anything—the bet is that one or two of them will break out, earning enough money as a bestseller to pay for all the rest.

According to Rachel Deahl, who has covered book deals for more than a decade as news director for Publishers Weekly, “There’s a saying in publishing: 80 percent of authors fail, and the 20 percent that succeed pay for all the failures. It’s about building up big bestsellers. They are the people who pay for all the people who don’t make it.”

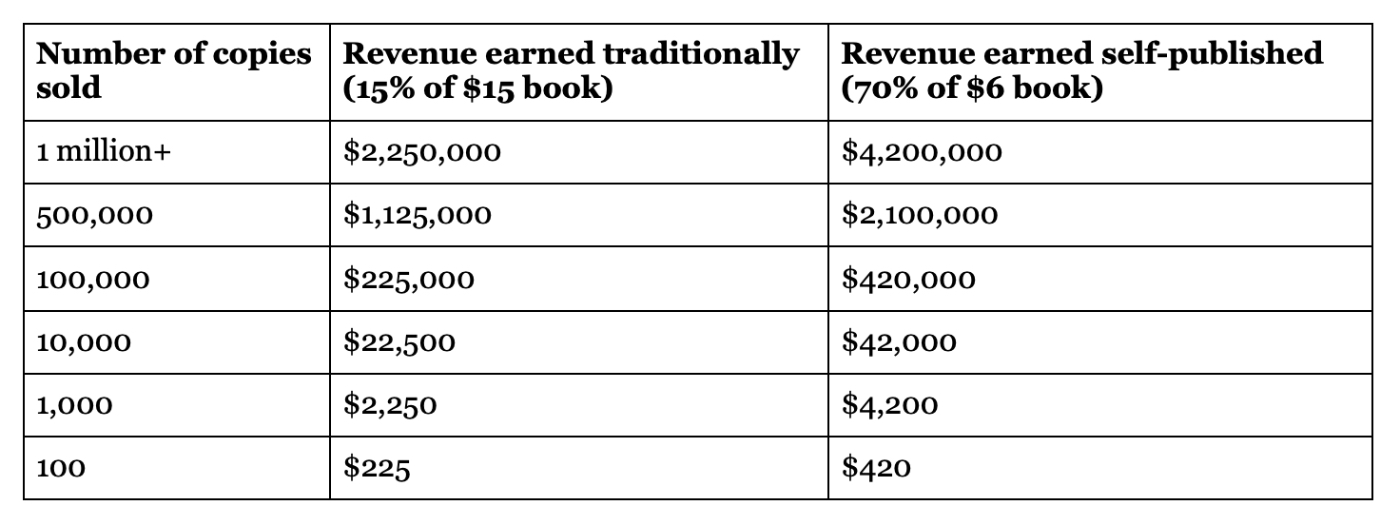

And if most books sell between 0 and 1,000 copies, then most books are earning between $0 and $42,000 in a year. Earnings of $100,000 only happen once an author has sold 45,000 copies traditionally or 24,000 copies self-published.

“The fantasy that you’re going to become an author and get rich doing it is misguided,” Deahl says. “Very few people become rich, and very few people even earn a living doing it. Most books don’t succeed. When you think about it, it takes some people 10 years to write a book. Even at $15 an hour, over 10 years you will be paid more at minimum wage than you will earn on the book.”

As an author, this is distressing. If I can spend two to three years (or more) writing a novel and the most probable scenario by far is having it sell a couple hundred copies on Amazon, perhaps it’s time to face the fact that writing books is little more than a hobby—something that might make a couple hundred dollars, but will never earn me a living.

But why is that? Certainly there are more writers than there are readers—though publishers haven’t quite caught up with these changes in the market and the supply. Perhaps it’s not books themselves, or even the market for them, that are the problem—perhaps it’s the way we’re selling them.

Subscriptions and serialization: Will the future of publishing look like the past?

Wired founding editor Kevin Kelly wrote one of Silicon Valley’s most beloved missives back in 2008: “1,000 True Fans.” The idea is that it takes only 1,000 “true fans”—that is, devoted believers—spending $100/year on a product for a creator to earn $100,000. Every year, there are 83,397 books that sell more than 1,000 copies—the problem is they’re only earning $4.20 per copy at most.

Using our current publishing model, if an author sells 1,000 copies of a book, she will earn $2,250 if published traditionally or $4,200 if self-published. But using Kelly’s model, an author could release a new book chapter every week, charge readers a $9/month subscription fee, and earn $108,000/year—from those same 1,000 readers.

Non-fiction writers are already doing it. According to this chart by Alexey Guzey, there are plenty of Substack writers putting out quality non-fiction content for their followers and monetizing it—earning hundreds of thousands of dollars annually, just from reader subscriptions. A couple of them are earning around $1M!

The chart was last updated in November of 2020, and Substack has since removed the leaderboard that made this information publicly accessible, but according to an update from The Information, Substack’s top 10 writers have doubled their subscription revenue from late last year, with subscription sales rising to $20M as of March of 2021.

If nonfiction writers can be making this kind of money, could their approach work for fiction? It did once.

From August 1844 to January 1846, Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo was published in 18 installments for The Journal des Débats, a French publication with 9-10K subscribers. It was basically “Game of Thrones.” Readers were rapt—they could not wait to get their hands on the next installment. Dumas, meanwhile, was not only paid by the newspaper per installment for his work (by the word), but also grew the popularity of his work over the entirety of the time it was being published.

“The ‘Presse’ pays nearly 300 francs per day for feuilletons to Alexandre Dumas, George Sand, De Balzac, Frederic Soulé, Theophile Gautier, and Jules Sandeau,” Littell’s Little Age, Volume 10 wrote in 1846. “But what will the result be in 1848? That each of these personnages will have made from 32,000 to 64,000 francs per annum for two or three years for writing profitable trash of the color of the foulest mud in Paris?”

That “profitable trash” earned those writers an annual salary of between $202,107 to $404,213 in today’s dollars—and the obvious disdain of the Littell writer who, even then, preferred the virtue of a bound and published book. The same volume goes on to say that Dumas earned about 10,000 francs ($65,743 today) per installment when he was poached from The Presse by The Constitutionnel in 1845.

Fiction Platform Breakdown: Wattpad, Inkitt, and Amazon

The serial novel is already making a comeback. On the apps Wattpad and Inkitt, writers can publish chapters as soon as they are written, and followers read and comment on those chapters, offering feedback authors can use to write more of what their audience wants. On Wattpad, 90M users spend an average of 52 minutes per session reading books online. The Inkitt app has 2M users.

But authors don’t make money on these platforms—readers read for free. There was some hope that would change when Wattpad debuted Paid Stories in 2019, allowing readers to pay for chapters using micropayments—three coins unlock the next chapter—but the author does not get to decide whether or not their content is part of the paid program, the platform does based on how the book performed in its free iteration. And even the best-paid authors aren’t making a living doing it.

Two years into their paid program, Wattpad announced reaching only $1M in author earnings, split among 550 writers. All things being equal, that’s only $1,818 in total earnings, per author, over a two-year period—and all things are not equal. The more likely scenario is that a small percentage of those 550 made up the bulk of the earnings with pennies left for the rest.

One Wattpad author, who wished to remain anonymous, told me her book reached 20M free reads on the platform before she was invited to go paid last year. Since then, she has earned a couple million more reads and has averaged $500/month in earnings with her highest month topping out at $1,000. And this is with a YA romance novel—one of the best performing categories on the site.

Now Amazon wants to get in the game. In April of 2021, they announced the launch of Kindle Vella, a Wattpad competitor that allows authors to publish their books serially. Thus far, no marketing initiatives have endeavored to promote these pioneering authors—but it’s no matter. Writers pour an estimated 1.2-1.4M books onto Amazon each year and, even if every book sells only 200 copies, the platform will earn 20-50 percent of each sale and win the whole game.

Still, if 20M people are willing to read a book for free and a couple million more are willing to pay for it, then there is at least a market for serial fiction. The problem is that if authors are only netting $6,000-$12,000 in a year for their work—maybe we don’t have the right platforms yet.

Creator Economy Platforms: Substack and Patreon

I decided to serialize my own novel, releasing one chapter per week from September 2021 through June 2022, and I turned to Substack and Patreon for the experiment. Unlike Wattpad and Inkitt, both platforms allow authors to monetize their work, with readers subscribing directly to their favorite writers.

Publishing on both platforms is free, with Substack and Patreon earning a percentage of income—Substack charges 10 percent of earnings plus a Stripe fee, Patreon charges 5-12 percent of earnings depending on what payment processing services a creator wants access to. And because both platforms allow the author to maintain the rights to their work, there is nothing preventing us from putting our books up on Wattpad, Inkitt, or Kindle after the subscription period ends.

I created accounts on both platforms to test the waters—though each has its share of pros and cons. Patreon, for instance, doesn’t have a free pricing tier which means I would have to build my platform elsewhere before attempting to sell into it. This is why almost all of the 15 authors currently earning more than $4,000/month writing novels on Patreon built their audience on Royal Road, a free serialization platform that lets authors share their chapters as they are written.

“There's sort of a fixed model for how serialization works in terms of generating revenue—where you start off building an audience on Royal Road and then from there you start a Patreon,” the author Travis Deverell tells me. “And there's an expectation that your Patreon will have a certain number of advanced chapters ahead of what goes for your Royal Road.”

Deverell’s pen name is Shirtaloon and he earns $28,532 a month from his Patreon supporters. Readers can choose whether they want to read his chapters one week ahead ($1/month), two weeks ahead ($5/month), or four weeks ahead ($10/month) of Royal Road. He also has pricing tiers at $15, $20, and $50 a month which have no additional benefit except supporting an author they love—and fans pay it.

But Royal Road is very genre-specific. In fact, it tends to attract an audience that isn’t well represented elsewhere: hyperniche science fiction and fantasy genres such as litRPG, isekai, and power progression. “Royal Road is such a big platform for building audiences, but the audience is looking for fairly specific stuff at the moment,” Deverell says. “Like Wattpad is great for YA fiction, but Royal Road is a much better fit for what I’m doing.”

Patreon also isn’t well-suited to writing. The author Emilia Rose earns more than $120,000/year serializing erotica on Patreon but plans to move her 3,000 patrons to Litty, a new startup promising to be the “Patreon of fiction” when it launches this fall. “Patreon has set up its website like a blog, which makes the platform incredibly difficult to use for ongoing stories,” Rose says. “Since I release two to five chapters per week of a single story, it is difficult for readers to find previous chapters. From a reader’s perspective, it’s not a great experience.”

Substack, on the other hand, was built for writers. Chapters are delivered via email and books can be separated into “sections,” making the experience easy on the reader. And unlike Patreon, I don’t need to build another platform elsewhere before I can monetize my work. Instead, I can build my audience directly on Substack, writing a free newsletter that upsells into a paid version.

The downside of Substack is that I don’t have access to all the pricing tiers I can get with Patreon—Substack only allows me to have one monthly subscription fee, plus a “lump sum” donation bucket—and I know pricing tiers are a must. After all, why would a reader pay $5/month to read four chapters of a book when they could buy a whole book on Kindle for $1.99? (This is why there are plenty of writers writing novels on Patreon earning $200/month—and plenty of Kindle authors earning $200 total).

There has to be added value. I want my readers to have the option to join an exclusive online community, be mentioned in the acknowledgments, or even write the foreword for my book. When the book is complete, I want to be able to send autographed, hardcover collector’s edition to premium subscribers, throw a wrap party for my patrons, or even elope to a gothic estate in France to write ghost stories together afterward.

These kinds of value adds are, after all, how the science fiction author N.K. Jemisin achieved Patreon success. Her work has since become critically acclaimed and has won numerous awards including a Hugo Award and, in 2020, a MacArthur Fellows “genius grant,” but when she first joined Patreon, she simply wanted to make $5,000/month so she could quit her job as a psychologist. She did—and she had five superfans paying $100/month for signed, printed copies of her books and nine paying $50/month for signed-author copies. That’s $950/month in revenue just from her top 14 fans! Authors can’t afford to miss out on that kind of patronage.

Even without pricing tiers, I think Substack is the better bet—the whole process is already built-in and has been proven to work for non-fiction authors. And Substack has made moves to invest in fiction. On June 9th, Business Insider announced that Substack hired Nick Spencer, author of Captain America and The Amazing Spider Man franchises to entice comic-book writers to the platform. They also announced, in August, their first round of investments in comics writers.

Indeed, we may be seeing the beginnings of a surge in fiction writers on the platform. The fiction author Etgar Keret joined the platform in August and the novels The Very Modern Vampire and Something Deep are both serializing on Substack. In fact, more authors are putting their novels on the platform every day which makes me wonder whether I should stop looking for where the literary writers are, but where the literary readers are. And we are definitely actively reading (and paying to subscribe to) literary non-fiction on Substack. Maybe we’d read literary fiction there too.

After all, Truman Capote’s novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s was serialized in Esquire before being published by Random House in 1958. The Martian started out as a blog on Andy Weir’s personal website before it was self-published, then traditionally published, then turned into a blockbuster film starring Matt Damon. And in 2020, Lena Dunham serialized her choose-your-own-adventure novel Verified Strangers via Vogue.com.

That’s what Dumas did too. The Count of Monte Cristo was published, not in a literary journal, but in a newspaper—where people were getting their weekly news. Why wouldn’t the sort of people who follow literary journalism and societal critique be the same sort of person who enjoys seeing the Edmond Dantès flee the Chateau d’If via body bag? And Substack is rapidly becoming the newspaper of note for millions of readers.

Of course, to make it on Substack, creators still have to build a platform, publish consistent work to that platform, and attract an audience to that platform, on top of actually writing something good—none of this is easy. But I’m going to run an experiment anyway. With creator economy technologies on the rise and subscription models rapidly proving their viability, I think there’s hope for fiction after all.

We just have to write a new story.

Elle Griffin is the author of a newsletter about writing called The Novelleist. She is about to publish her first novel as a serial via Substack.