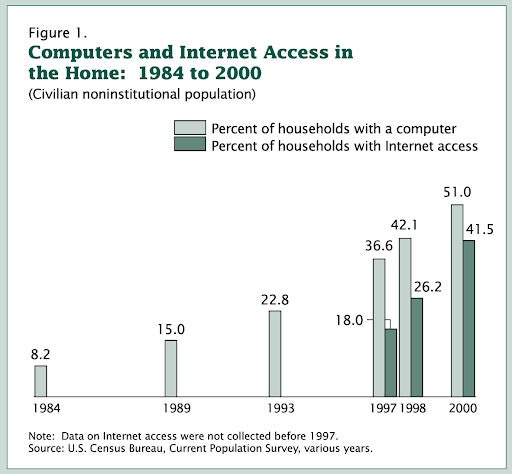

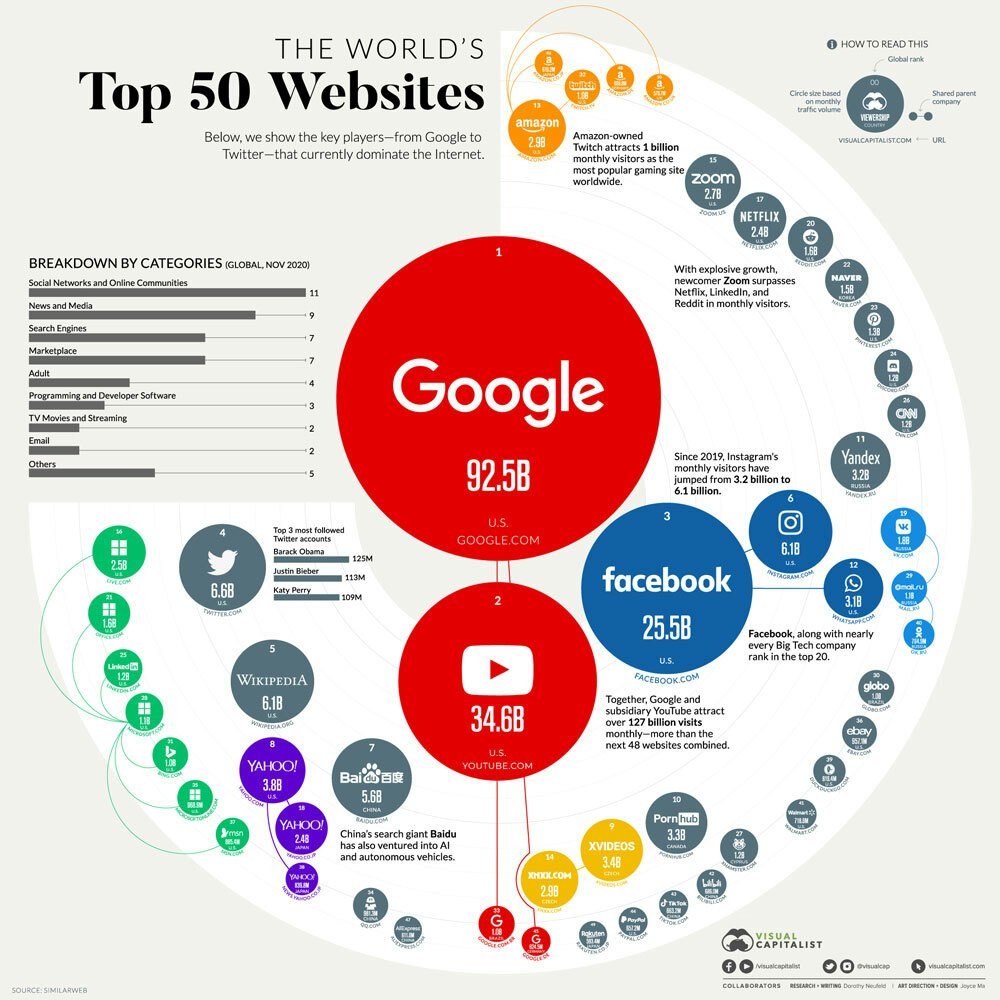

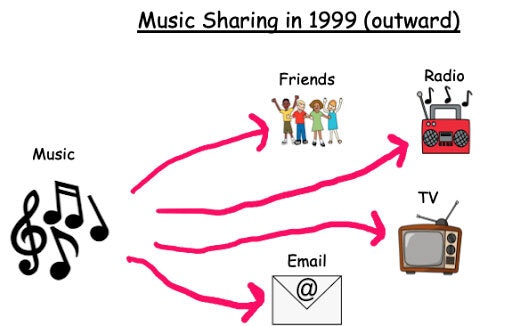

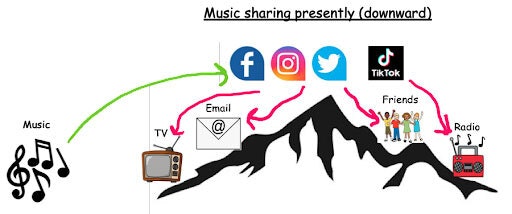

| | The internet isn’t just about garnering traffic. You gotta harness that traffic.Virality, regardless of generation, is almost always accompanied by commercialization. Hampsterdance was no different. As it rocketed in popularity, there were various attempts to monetize Hampsterdance across an array of mediums. As a writer attempting to build an audience on Substack without any previous platform or notoriety, these attempts strike a chord. How were attempts to monetize and build an audience back then different from today? Looking back at the Hampster Dance crew’s monetization attempts showcases how centralized today’s internet is, and what the contrasts are for amateurs (like me with my Substack) hoping to go pro with internet content. If I were to go viral today, there’s not much I can do to drive visitors to further engage with my content. It’s either a subscribe page, a post, or my landing page, nothing else. If millions of people were visiting my site, and I wanted them to do something besides read a post, like buy a t-shirt or a mug, I’d need to send them to an entirely different URL. In this way, my situation’s no different than the one faced by the Hampsterdance team. In many others though, it’s different. Hosted on a GeoCities website which allowed users a platform to create and publish websites for free, Hampsterdance was nothing more than rows of different hamster gifs, all dancing along to a sped up—think, an Alvin and the Chipmunks style pitch—version of the song “Whistle Stop” from Disney’s Robin Hood. The site was created by Canadian art student, Deidre LaCarte, in a contest with her sister and friend to see whose website could generate the most traffic. By the end of Hampsterdance’s first week, she had 800 hits. After roughly a month, the website had over a million hits. While a million is nothing by today’s standards, it was massive at the time. Initially, it was like striking oil without a well—a precious resource, web traffic, leaking without being monetized, in real time. Something had to be done to monetize the flow. Hampsterdance had a patchwork quality; it combined gifs pulled from the internet with sped up unlicensed music. LaCarte didn’t create the hamsters or the music, but she was the one who combined them. This presented questions of who ultimately owned what, many of which are still relevant today. Although important, my focus is on the Hampsterdance website as a whole, not its component parts. The problem for capitalizing on Hampsterdance was that free GeoCities websites were throttled, meaning each site was only allotted a certain amount of bandwidth. This meant thousands of visitors were coming to the site, only for it not to load. No animations, no sounds, nothing, save for confusion. At that point, someone unaffiliated with the creation of the site swooped in to purchase the domain Hampsterdance.com. From there, they just copied the Hampster Dance code onto their own URL and hosted it themselves. Since the original was hosted on an unintuitive GeoCities domain (http://geocities.com/Heartland/Bluffs/4157/hampdance.html, to be precise) Hampsterdance.com had a much higher degree of discoverability for those who’d heard about the meme and wanted to find it online. Paradoxically, the Hampsterdance GeoCities page in some ways offered more flexibility in terms of skinning, and therefore branding, than does my Substack. Although no one would want it, I can’t autoplay music, I can’t insert multiple gifs in a single row, and I can’t insert tracked advertisements on site. What’s more, on the off chance I were to ever go viral, I can’t even nest pages on Substack, much less insert an iframe. Only written classifieds. This means less effective advertising and a manual, email-based method for accepting payments for said advertising. Substack users can have a custom URL though, which in the context of earned discoverability, is far more powerful than any of the aforementioned features. However, because my site is hosted by Substack, any SEO juice that my content creates is indexed to Substack.com and not my own URL. So while the URL for my Substack may be easier, the organic discoverability of the site is probably lower than the original Hampsterdance. Given this was 1999/2000, branded merchandise wasn’t the first thing LaCarte and her team strove to create. Likely because in 2000, only 16 percent of the working age population were internet shoppers. Nonetheless, even if LaCarte and her team had wanted to, they were bereft of the simple e-commerce options which exist today such as Stripe, Shopify, and Squarespace. Amazon and eBay may have existed then, but it was quite difficult, if not impossible, to set up a personal marketplace at the time. Not only did very few people shop online then, this was long before the formation of PCI (Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council), which was formed (and still exists today) to ensure the security of online card payments. Basically, the barrier to entry, in terms of both time and money, into the e-commerce foray, was just too much to bear. | | (via VisualCapitalist) Now, it’d be preposterous for an online payment platform to not be PCI compliant. What were disparate components in the year 2000—online carts, card acceptance, processing, and security, and even backend logistics—have now been unified under platforms such as Shopify and BigCommerce. | | Instead of merch, LaCarte and team focused on what they believed was the website’s hook—its music. With that in mind, they brought on a partner to produce a less legally fraught, more commercializable version of the Hampster Dance song. The result was “The Hampsterdance Song” by The Boomtang Boys. The song climbed all sorts of charts, even making its way to the top of the Canadian singles chart and its video was played all over MTV and MuchMusic. But, there was still no CD to buy. MTV and MuchMusic only dabble in music today. If ‘The Hampsterdance Song’ were to snake its way around the internet, it’d rely on a combination of YouTube, Spotify, Apple Music, and Pandora, not cable TV. Yet, because the original Hampsterdance song was just a sped up Disney song, and Disney wouldn’t clear a sample, it had to be re-recorded. This implies there’d still be the same delay in getting the music to market. And, had the song not been re-recorded, Spotify, YouTube, etc. likely would not leave the songs up on their respective platforms. Either way you look at it, the virality of the song would’ve been dependent on only a small handful of platforms. The distinction between eras lies in how those platforms are gatekept and how they’re discovered. To get the song on a cable network, or have it picked up by radio stations, there was more or less a single point of entry into those spaces. As in, there was literally a person who decided whether or not and how frequently the song would be played. This also meant that discovery of the song was more active (versus passive). Someone needed to be tuned in to gain access or to come across the song. As the internet was still nascent, the likelihood of discovering it online was still low. Presently, the entryways to popular platforms on which the song could be heard aren’t guarded by people. They’ve been digitized via algorithms, checkboxes, and terms and conditions. Thus, potential for virality has less to do with a specific individual’s taste or one’s relationship to the gatekeeper at a TV or radio station, and more to do with popularity, especially popularity supported by data such as plays, time spent, visits, streams, etc. As for discovery, today’s platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and embeds of all stripes facilitate a more ambient discovery for consumers. If you’re scrolling Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, or even reading a Substack, you could come across an embed of the Hampster song. You don’t need to be on a music website to discover music, content’s visibility isn’t constrained by what it is. As in, search and social networks have superseded categorization of content. Sports and music and politics can marinate together in the same muck alongside posts from Dan Bongino and The Dodo. | | | | This means content flows downward, instead of outward. A GeoCities website needs to be shared outward—word of mouth, email, radio and television stations. That same site today would have clips posted on Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube and would flow, with downward momentum, via those apps’ internal messaging systems, shared URLs on other websites, and private messaging (email and text, primarily). Think of it as putting a ball at the top of a hill and hoping it hits as many bumps (nodes) as it can on the way down. But, the downward flow doesn’t work if there’s not a network or centralized site from which the original content can flow. Even now, if I search for “The Hampster Dance,” my first two hits are Wikipedia and Youtube, the #5 and #2 most popular websites in the US, respectively. If I don’t have entries on both sites, my growth would be seriously hamstrung. |

|