Hi, readers! It's Li here. Today, I have a guest post for you from fellow Every writer Babe Howard. It's a deep investigation of a new technology: a robotic printer that can be programmed to produce real oil paintings on the the level of a human master artist. Will this technology democratize artistic expression, making everyone a painter? Will it change how we think of who an 'artist' is? How does technology change what it means to create? In his conversations with the man behind the robot, and through his own artistic experiments with it, Babe explores these questions and more.

The canvas appeared, blank and pixelated, captured from multiple angles on a range of cameras. One of them observed the painting area in its entirety: a ring of wiring, computer screens, and hard drives, at the center of which stood an industrial work table. That’s where the canvas sat, rather than an easel, facing straight up. A pair of hands entered the bottom of the frame, priming it in swift, professional strokes—the work of a trained painter. Then they disappeared, and the robot took over.

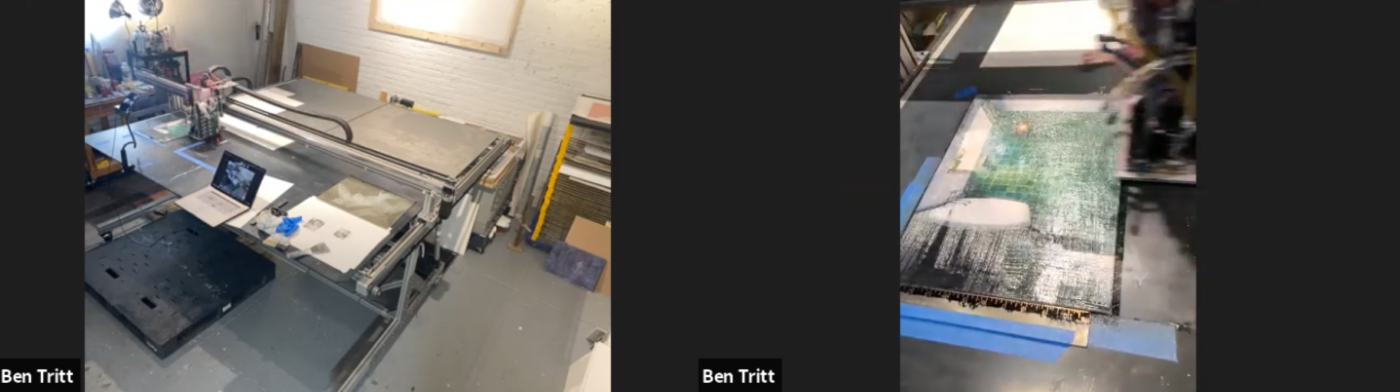

Straddling the upper half of the table, the apparatus looked like it had been grafted on, a cybernetic alteration of sorts. A thick metal bar ran lengthwise, holding on its end a complex, box-shaped device with colored tubes twisting out from the back. All of the hardware was secured to two rails on the table’s sides: between its horizontal and vertical mobility, the device appeared able to cover every inch of the surface. For now, though, it just needed to tend to the white rectangle in the lower left corner.

From off-camera came a tapping noise—someone keying in a command. The digital printer whirred to life, heading for the corner one direction at a time: a bit down, a little to the left. Reaching its destination, it stopped with a jerk, then bore down on the canvas, preparing to lay down the first layer of my painting.

In a Brooklyn warehouse space, not far from where the Hudson River empties into the Atlantic Ocean, there exists a robotic “printer”—a deceptive, nearly humble title for a machine that produces real paintings with uncanny mastery. Its current iteration consists of a mobile printer head mounted to a metal bar, equipped with 200 nozzles in place of a brush, and wired to a handful of design softwares. Through that connection, the printer receives instructions; unlike parallel innovations in writing, for instance, it does not generate work on its own. To begin painting—a process during which the printer head never makes physical contact with the canvas—it needs a base image. To date, artists have used the device to make entire paintings they might not have attempted on their own, or to provide specific augmentations to semi-complete works. The printer’s intelligence is not artificial, but rather “extended,” to use the term preferred by the machine’s creator, Ben Tritt.

The Artmatr studio in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Photograph by Campbell SilversteinTritt, a classically trained painter and entrepreneur, has always kept one eye on tech. In the 1990s, while establishing a studio art school in Israel, Tritt began feeling that the world of fine art was almost entirely disconnected from the burgeoning tech sector.

“I was really dissatisfied with the limitations of that kind of education,” he told me, “because of its lack of integration with digital.” Over the next decade, Tritt watched as artists in other mediums embraced digital innovation wholeheartedly. Word processors completed their takeover of writers’ offices, computer programs replacing typesetter’s tools and cutting rooms. Digital cameras went from a luxury consumer item to the default tool for shooting films of all sizes, before entering everyone’s pockets via the iPhone. The software instruments of tools like Garageband made space for more people to create music on their laptops.. But painting, in Tritt’s words, remained “the last creative domain to be transformed by digital technology.”

Returning to New York, his hometown, in 2008, Tritt found the U.S. firmly in the era of the Screen. Although it would be a few years before he pivoted fully to digitization, Tritt’s appetite for interdisciplinary collaboration had grown exponentially. To feed it, he sought to work with artists and workers from beyond the borders of fine art. It was on one of those projects—a 2014 show in Manhattan’s Bryant Park that joined painters and architects—that he began developing an organized approach to his new passion. Listening to the “tough conversations” between his fellow artists and their engineering-minded counterparts, Tritt began strategizing ways to facilitate clear, productive relationships between members of each discipline. “I’m more interested in that communication than anything else,” he explained to me.

Tritt was quick to remind me that cross-disciplinary collaboration is not new to the art world. As a historic example, he offered the Italian Renaissance—the peak era of fresco painting—when artists had to be “fluent in [both] the engineering and the design,” since their work was the final step in the architectural process. How, then, could he leverage a passion for open dialogue into a relationship across disciplines—art and architecture, even engineering—that yielded actual work?

To answer that question, Tritt did not jump straight to technology, instead considering the question of collaboration from a logical, head-on zone: real estate. Art-meets-industry projects such as Newlab and Pioneer Works were cropping up near his Brooklyn neighborhood, offering workspaces and communities to artists in the trendy wrapping of converted industrial buildings. Tritt, however, “felt there was a piece missing.” He had worked with artists and scientists separately, but had found difficulty in bringing them together, mostly for reasons of composition: the informal cohorts had been “either not a diverse group of people” or “too diverse, in the sense [that] the people... don’t have a reason to be together.” Establishing a proto-coworking space for artists and scientists was a nifty idea—but in order to function internally, they needed a reason to gather.

“For better or worse,” Tritt told me, technology “engages people’s imaginations right now” on the level architecture did centuries ago. “My soul craves that kind of reintegration.” A year after the Bryant Park show, he came across a way of quenching that craving at the most tech-friendly locale imaginable: MIT had hired Tritt as a visiting professor. Weeks into the semester, he connected with a group of students at the school’s Media Lab who were working on an early-stage concept for a robotic painting tool. Once again, Tritt found himself joining forces with engineers—only this time, the tough conversations were a necessity, not a roadblock.

Ben Tritt at the Artmatr studio.After an invitation to the University of Konstanz, the team began making repeat trips to Germany, doubling down on hardware development. As they pulled apart consumer-grade printers made by familiar giants like HP, Tritt was horrified at what he found inside: low-quality inks, and “closed system” cartridges that, in the footprint of Steve Jobs, gave users little room to customize—and none to find other options. That informed the first iteration of the mounted printer design, which set a baseline for openness and customization at every possible turn.

The printer head “paints” by running back and forth along the metal bar (or “gantry”), executing the image in a series of passes from top to bottom of the canvas. The painter may stop the printing process at any point between or in the middle of those rounds, to make alterations of their own.

The printer’s software programming takes cues from inkjet printers, as well: based on a CMYK (cyan, magenta, yellow, black) color model, it tells the machine’s ink plates to recolor, sharpen, or obscure parts of the digital image the device has been fed, depending on the parameters set by the user. In Tritt’s view, the device manages to approximate a classical order of operations. “This is the way a 17th-century painter would have worked in Florence,” he told me.

After years of research and development on software and hardware spanning multiple continents—the ink compounds are supplied by a Japanese company and developed by chemists in the U.K, while two lead hardware engineers run a lab in Israel—Tritt and his team had a piece of technology that they felt was ready for use by contemporary artists. He finally found his real estate: a waterfront warehouse space in Red Hook. Securing a $1.5 million seed round from venture backers, he had the place, the tools, and the cash—along with a startup to link it all to: Artmatr, which promised to meld “contemporary painting technology” with “ancient technique.”

Next came the painters. Barnaby Furnas first worked with Artmatr on his 2018 series Frontier Ballads, a subversive twist on mythic American images. Using an early version of the printer developed by Artmatr master printmaker, Jeff Leonard, that put the gantry on wheels, Furnas was able to work on the ground, supervising the device up close as he pushed it up and down the canvas. (That iteration was leased to an artist the company is working with to open a “satellite lab” in India, but Tritt and the company are at work on a future version that might be able to wheel itself directly up a wall.) Maria Kreyn has been a close Artmatr collaborator in a similar vein, applauding the creation of “robotic tools for artists to complement and augment their hands-on analog practice.” The photographer Eric Fischl has recreated his pictures on canvas, with the printers enabling a far shorter process than his experience doing similar work by hand. Jeff Koons is currently using different configurations of Artmatr's tools for projects in multiple mediums.

Each artist is bound to use the printing technology differently, but its standard appeal is clear: more room for experimentation, less chance for risk. As an analogue, Tritt cited Francis Bacon’s famous late-career tendency to paint on unprimed canvases—which meant a dissatisfactory stroke resulted in a trashed painting. “That element of risk is what made his work so great,” he explained. “Part of what we’re doing is being able to engineer those happy accidents.” The experimental spirit, he believes, can be preserved, while retaining only a fraction of the financial strain it is commonly understood to create.

Take Koons, whose Gazing Ball series augments his own replications of da Vinci and Manet classics with blue glass spheres embedded in the canvas. “I know he wants to come up to that painting, take a paintbrush, and just fuck it up,” Tritt says, a knowing smile on his face. “But he’s not going to risk throwing out ten months of work and $200,000...if we could recreate the whole thing in a day or a week, he’ll do it ten times until he gets it.”

I asked if Artmatr's programming, in the aim of helping painters to “get it,” can preserve any room for the unplanned. Tritt spoke of his team’s dedication to “leaving open space so that we can stumble into interesting mistakes.” He grew animated: “We can actually hardwire those conditions into the tool,” he explained, leaning closer to the webcam. The circle of innovation here appears to rest on baking things in, leaving a fresh observer to Tritt and Artmatr's work wondering: Can a piece of art be truly spontaneous in its creation if the artist has to tell her tools not to act?

Tritt appeared unfazed by the question—or at least willing to work within its grey area. Everyone uses the robots differently, he reminded me, “and the effects are totally different.” The process he has cultivated in Red Hook may necessitate more structure and rules than an artist standing over a blank canvas in their studio, but he finds it no less authentic. Users “won’t be able to recreate” what others have done with the printers, Tritt assured me. The artist’s vision is still singular—only the brush has changed.

Artmatr's printing technology retains the C/M/Y/K color scheme of consumer-grade printers. Photograph by Campbell Silverstein“Before I ask: what is a work's position vis-a-vis the production relations of its time, I should like to ask: what is its position within them?” the philosopher Walter Benjamin once wrote. The year was 1934, and Benjamin’s native Germany was at the center of two separate upheavals: the advance of fascism, and media innovation. Having fled the country two years earlier as Hitler rose to power, Benjamin was concerned with literature’s function amidst the threat of state violence. In “The Author as Producer,” a never-delivered address written for the Institute for the Study of Fascism, Benjamin identified the rapid expansion of the newspaper industry as inducing “the melting-down of literary forms.” “Authority to write,” Benjamin said, “is no longer founded in a specialist training but in a polytechnical one, and so becomes common property,” which “questions even the separation between author and reader.” In other words: expertise is in high supply—because its meaning has shifted.

Still, Benjamin had reason to be optimistic. The newspaper, “where the word is most debased...becomes the very place where a rescue operation can be mounted.” Printing technologies had at once been seized by the state, for propagandistic use; and by the people, to express dissenting opinions that risked suppression or worse. Given this split, Benjamin decided, writers had “to decide in whose service he wishes to place his activity.”

Like much of Benjamin’s writing on art, politics, and their inevitable intersection, “Author as Producer” remains relevant today, not just to writing. As the “creator economy” grows in popularity as both a concept and a reality, calls to dismantle gatekeeping and “democratize” everything, from production to consumption, are ringing across countless genres and media forms. Smartphones promised to turn everyone into a photographer; now they’re used by established film directors. Podcasts and newsletters, whose booms are at different stages, depending on who you ask, have joined modern art as the butt of “anyone could do this” jokes. Of course, the ability to make a movie on your phone is not the same as having the connections and opportunity to sell that movie to a studio, the same way my eventual use of Artmatr's printer would be markedly different from Jeff Koons’—only one of us holds a world record for the highest-grossing piece of art sold at auction. As more creators begin identifying as both authors and producers, it is worth asking what it takes to make a living off either of those titles: the technology exists, but does everyone have the resources to use it?

Ben Tritt read “Author as Producer” while studying postmodernism at SUNY Albany in the early 1990s. He was struck by Benjamin’s influence on the movement—particularly the theory that photography and cinema had helped to destroy the concept of “originality.” Meanwhile, Benjamin’s anticipated “death of the Original” had migrated to software: something called Photoshop was beginning to make the rounds, aiding in reproductions and alterations of existing artwork and images. Digital cameras, still and video, were growing in popularity. Almost every visual art form was rocked by digitized means of production—except painting.

Artmatr's website identifies the company as “an art/tech playground for anyone, of any age, technical background or discipline, to make stunning, unique artworks unlike anything else available today.” When we first spoke at the beginning of 2021, Tritt revealed that one of his main goals in building a startup was to make its technology available to anyone with an internet connection—either for free or “ridiculously cheap.” He recalled examining HP cartridges in those early development days at MIT, and the two-pronged nature of his frustration: “They sort of rip you off,” he said, restraining himself—but even worse, the closed-system approach, which Steve Jobs found so effective for selling computers, becomes even more nefarious when applied to artistic tools. “The machines and business model conspire against creativity,” Tritt said, channeling Benjamin. The follow-up goal, then, is to go beyond democratizing availability, and “totally blow up the business model.”

At the time of our conversation, Tritt did not provide details on how painters would handle sales of the work, only that they would be able to video conference with the Artmatr team to work on paintings remotely, dictating instructions to Tritt and his team while they handled the printer in person. I asked him if the jump from interdisciplinary collaboration to remote painting was spurred by the pandemic-imposed uptick in remote work and videoconferencing. “This was my plan from day negative five,” he insisted, mentioning that the early days of the vision were concurrent with the coworking space phenomenon. But Tritt found himself “hamstrung” by a lack of computing power. “Because of Covid,” he continued, “it’s accelerated to a point where it’s now doable.” Around the time he participated in his first Clubhouse conversation (and “loved it”) Tritt signed up to install state-of-the-art streaming software—the kind used by Broadway theaters during the pandemic—in the warehouse after his next phase of printer development. Artmatr's multi-camera livestream could reach any platform they wish, he said. “We can create a larger space online for people that are interested in this.”

An iPhone camera is rigged to record and livestream the painting and printing process. Photograph by Campbell SilversteinWhen I wondered if that space-making extended to installing the printers themselves in remote areas, too, Tritt nodded enthusiastically. “Once we can find a way to produce these machines so that we can sell or lease them,” he explained, “I think we can get these set up all over the world for very low prices.” Tritt smiled, wondering at the possibility of painters making their own inks for the printers, not unlike a source code made open to users. Leaning closer to the camera again, he widened his vision even further: “We can put these in slums in any part of the world,” he said. “They don’t need running water...as long as they have a cell phone connection, kids can be making work and selling work.”

The pandemic-era pivots in remote work and entertainment had yet to provide full blueprints for making and selling outsider art, but Tritt seemed confident the finer points would work themselves out. In his telling, the desire to disrupt the fine art world may have been borne of its refusal to welcome digital innovation; but it had come to work in service of a greater purpose: making the painting experience “gratifying and central,” he told me. “And cheap.”

“We can start with any digital file, really,” Pip Mothersill told me from the warehouse’s video feed. A member of the original MIT team that worked on the printer, Mothersill is a British designer and technologist, and Artmatr's head researcher. She also happens to be married to Tritt. Husband and wife appeared in separate boxes on my screen, Tritt priming the canvas near the dormant printer while Mothersill booted up its software on a nearby desktop computer. Leonard, the printmaker, stood nearby, while Ian Jarvis, the company’s executive director at the time, joined from his living room in Manhattan.

Tritt had asked, after a few conversations, if I wanted to try the printer out myself. I was not in New York, but taking him up on the offer over Zoom felt nearly appropriate, after hours of discussing the boons and possibilities of remote painting over video chat. As Tritt finished priming the canvas with the smooth, efficient strokes of an experienced painter, the affable Jarvis delivered color commentary on our shared novice status as painters.

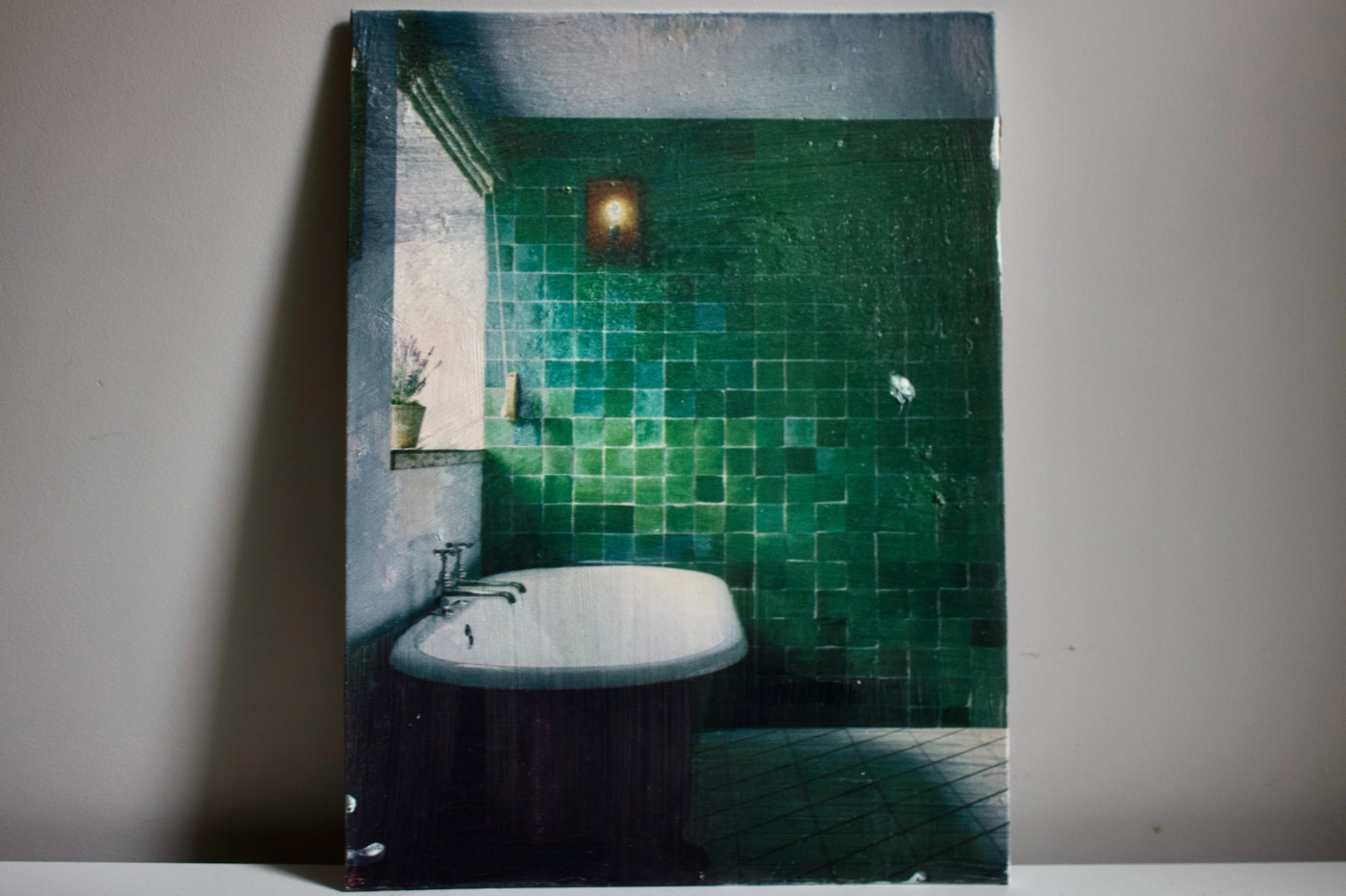

Having received advance instructions to think of what I wanted to ask the machine to paint, I delivered my idea and its overblown reasoning to Mothersill. Scrolling through my camera roll, none of my phone pictures had felt significant enough to be worth replicating with actual resources—so I had taken a more conceptual route, landing on a cheeky, possibly appropriate concept: the first image I remember logging as a child. A porcelain bathtub gave way to light green wall tiles, I explained to Mothersill. She listened patiently, then asked if I had a picture of the tub and tiles in question. Somewhere in my brainstorming, I’d forgotten the crucial fact that Artmatr's printers need an actual image—not just someone’s spoken components of one—in order to reproduce it with ink. Starting with an idea, as in traditional painting, is fine—so long as there is something tangible to complement it. Artists can use digitized sketches, photographs, or anything from the internet as a base. That file is then loaded into one of a handful of programs used by Artmatr, depending on the nature or type of image selected. From there, the artist and technicians have free rein to dictate how the printer goes about reinterpretation; coloring and clarity are tweakable settings.

With the wiry, soft-spoken Leonard leaning over her shoulder to provide input, Mothersill clicked over to Google, scrolling through options from Pinterest boards and lifestyle magazines before we settled on one that looked less like a real estate listing and more like my first memory. “We’ve had very high-end artists come in, do a quick Google search for an image, and then turn it into an amazing painting,” Mothersill told me when I asked if this method was a first. Still, she admitted, “there’s a little bit of pixel-pushing that we need to do to really make those random images shine as paintings.”

Pixels were pushed: Mothersill loaded the picture into the computer, where it ran through ZBrush, a “2.5D digital sculpting tool” and one of a few programs Artmatr uses, depending on the base image in play. With the blueprint locked in, Tritt explained that the printer was preparing to make its first pass down the canvas, comparing the process to the age-old painting style grisaille, in which the painter works exclusively in shades of grey: We would then “put the color on top of that” outline, he told me. Historically, he continued professorially, the technique had been used to translate three-dimensional architecture to a flat medium.

The dimensions came courtesy of the bathtub, reaching from the image’s tiled-wall background out to the viewer; and the shaft of light bursting through the window above the tub. The printer head captured the edges of both as it made its first journey to the base of the canvas, completing the initial, sketch-like round of painting—which was, in fact, very grey. It was also extremely clear, like a blueprint.

Tritt asked if I wanted to make any modifications before the colored ink plates were applied. I asked if we could distort the light—blow out the sunbeam to obscure half of the tiled wall, while strengthening the darkness of the floor so that the bathtub appeared to melt into black. He obliged, not with the printer, but his own hand. A long-haired flat brush entered the video feed closest to the canvas, making quick, precise horizontal strokes in the same direction as the printer’s motion. As Tritt expertly blended the light source into the wall, the image instantly grew more abstract and dreamlike—closer to whatever I had that might have constituted a vision. Jarvis chimed back in to explain that it was common for painters to jump in at multiple steps in the process, working with the machine, rather than responding to it. Clocking my astonishment, he asked if I had seen Tritt’s paintings. I had, on his website—layered, dimensional abstractions and portraits of crowds, children, deep-sea divers. But, with the exception of elementary school art class, I had never seen someone paint live before. It was transfixing—and minorly disorienting, having looked at the printer’s nozzles for the past few hours.

Tritt augments the printer's work with his own brush—a common choice amongst painters using Artmatr's technology.In a matter of seconds, Tritt was finished, and the printer began preparing for its Cyan round. Its head pushed forward, jerking across the gantry to apply the first layer of color, a robin’s-egg blue. It restored some of the wall’s definition—pushing back, I thought, on the manual work Tritt had just done.

Minutes later, the bathroom wall had turned purple, as the printer finished the Magenta pass. “You can feel how we’re just subtly tilting those colors,” Tritt said offhandedly. Where a painter might have mixed colors on a palette, the machine did it on the canvas, shade by shade. “It’s incredible how much of the time a painter spends in the studio is actually mixing colors,” he continued. “It’s pretty tedious work, but you can just essentially press a button, and have that done for you. It allows you to get to that creative stuff.”

Despite being in the “creative stuff” phase of the printing-painting process, I was having trouble considering the work-in-progress as my own: the original image, an unusually toney corporate stock photo, had come from Google. The printer had translated it to paper with eerie accuracy. And the only human alterations had been Tritt’s, based on my vague, stumbling instructions. I thought back to an early piece on Artmatr, which called the printers “unusual studio assistants” and wondered whether artists and assistants would consider extended-intelligence painting technology “a welcome break from enormous labor” or “a more sinister force.” Breaking into an industry is hard enough when mounds of aspiring artists have to compete for apprenticeships; what would happen if those jobs themselves ceased to exist entirely?

I was distracted by a new development: the yellow ink plate was turning the painting, finally, to the green of its source material. I made the lazy comparison of the near-instant color shifts to Photoshop’s “bucket” function, but Tritt took to it. “Everything on Photoshop is modeled after real things,” he pointed out, “but sometimes we get so used to seeing the simulation that we see the real thing and it’s kind of shocking.”

To match the colors of the image it has been fed, the printer executes a series of passes in different shades, one at a time.Ten minutes later, Tritt unmounted the overhead camera so that I could look at the real thing up close: nearly finished, the painting now held the raised detail created by the nozzles’ “brushstrokes.” It was convincing, particularly to the untrained, Zoom-borne eye: thin ridges over the shine of wet paint. There was one hangup: the Black ink plate had driven the bottom of the tub further into darkness, but almost fully restored the definition between the wall and the light, drawing the painting back toward the clarity of the Google image, and away from the ambiguous void I had imagined. It was not an error of the system, necessarily—Tritt and Jarvis are quick to speak of their commitment to letting artists “mess around for days, or weeks” after the machine has done its work—but more my own discomfort with calling the shots. To anyone not used to virtual instruction-giving, the process may need to be extended—or melded with some crash course in dictation.

Even when given an opportunity to ask for any final adjustments, either from the printer’s nozzles or Tritt’s hand, I demurred—in part because he seemed happy with the possibly-finished product. “It looks like a Vermeer,” he said, peeling the canvas from the work table. From Google Images to Vermeer has the ring of a compelling pitch, if Artmatr's technology were to become available to non-experts like myself on the scale Tritt was aiming for. But I wondered if all novice users would want to use existing images in the way I had—or, for that matter, like Barnaby Furnas or Jeff Koons. The yet-to-be-discovered class of painters Tritt often spoke of, those who grew up drawing with styluses instead of pencils, may have ideas trapped in their heads—and producing them on canvas is decidedly different from doing so on an iPad screen. Sooner or later, the Artmatr team may locate or create the infrastructure to send remote painting worldwide. Still, their current clients are largely established or trained painters. Welcoming artists with less training, experience and resources may require the company to innovate outside printing technology, in order to make the platform equally accessible and legible to a wider swath of users.

In the early 2000s, the renowned, digital-savvy director David Fincher put an entire film together before shooting a single frame. Using then-nascent previsualization software, or “previz,” to design the duration and dimensions of each shot in Panic Room—without needing an actual camera—Fincher subsequently found himself at odds with Darius Khondji, the painterly, Oscar-nominated cinematographer he had hired for film’s production. Fincher and Khondji had worked together before to successful results years earlier, on Se7en, but now, with an entire blueprint already made before the first day of shooting, Khondji found little room to bring his own visual impulses into play. He left the project—a decision for which Fincher did not blame him. “Darius is not a light-meter jockey. He wants to be part of the decision-making process,” he told The Guardian in an interview promoting the finished film, which he hired a comparatively greener cinematographer to shoot. “This movie did not allow that, and it was incredibly frustrating for him." In the two decades since Panic Room’s release, previz has become a widespread tool in Hollywood, particularly amongst blockbuster filmmakers with multi-hundred-million-dollar budgets. Most superhero extravaganzas have their action sequences designed years before a single frame is shot—sometimes even before directors or actors are hired.

In the two decades since Panic Room, previz has grown into a prime role in the filmmaking process as a logical way to mitigate risk in an era of bloated budgets, particularly in the U.S. But the path to widespread use has been bumpy, initially with regard to issues of labor: like plenty of other digital innovations, the rapid popularity of previz made it easy to pave over the the risk of excluding existing artisans—in this case, cinematographers—from the creative process, rather than integrate them in a meaningful way. Over time, that opposition evolved into collaboration, as digital tools became commonplace amongst film workers of all ages, for budgetary reasons as much as artistic ones. But the effect of previz, and technologies like it, on spontaneity—already a risky proposition in general for Hollywood projects without a filmmaker with serious pull, such as Fincher, attached—is murkier. However difficult it may already be to come up with new visual ideas while shooting on a greenscreen, the advent of movie-blueprints may have pushed cookie-cutter aesthetics even closer to becoming the norm. Against that backdrop of sameness, it is easy to anticipate that aspiring artisans who are less interested in tools like previz may not find room in the Hollywood system to indulge those whims. It is one thing for a well-established filmmaker to use their clout to forge bravely ahead. Will film workers with less notoriety be forced to compromise their ideals out of concern for their careers—or worse, when the more analog jobs cease to exist altogether?

When asked why he built and believes in Artmatr's technology, Tritt tends to bring up movies. As the least ancient art form, and one that is constantly undergoing digitally-prompted changes, cinema is a suitable point of comparison—or aspiration. Imagining a viewer’s hypothetical choice between watching a film and looking at a painting, “nine out of ten people will choose the movie,” Tritt told me. If art wants to change those odds, he believes, it needs to offer the same “immersive engagement” people look for onscreen.

We were speaking in person for the first time, near the back of the Red Hook warehouse, with the servers powering the dormant printer whirring behind us. Jarvis had just gone to Staples for office supplies, while Leonard was across the room tinkering with what looked like a robotic arm attachment. That left Tritt—as sturdy, loose, and talkative in person as he had been over Zoom—to fill me in on the massive pivot Artmatr had taken since the last time we had spoken.

At the time of my virtual painting session two months earlier, Non-Fungible Tokens had just begun to receive major media coverage. Meme artwork and videos from pop superstars were selling NFTs tens of millions of dollars, as primers on the crypto-adjacent craze (NFTs were born exclusively on the Ethereum blockchain of cryptocurrency) hit the front page of most tech and art websites alike, all explaining versions of the same thing: non-fungible tokens were unique, even if anyone could find the files online—and they were going to bring digital art to the auction house. Over the next few weeks, multiple arguments on the merit and dangers of a non-fungible arts marketplace began to brew, on everything from the environmental impact of minting NFTs to whether they could transcend the confines of the blockchain entirely, becoming some kind of norm for art purchases.

Tritt was paying attention. Still early in the push to make remote painting accessible to the masses and approaching another round of venture funding, he, Jarvis, and the Artmatr team saw a natural opening in the NFT marketplace. Rather than just helping artists create with the printers, they would start helping them sell the work, packaging all the digital assets generated during the process and selling the bundle as an exclusive. With the anchored excitement of someone who is very recently on to something, Tritt told me his startup had become a software company. He was half-joking, but the comparison had legs: like Apple, he explained, Artmatr's foundation was a piece of hardware. Now, they were offering “Production as a Service. PaaS,” Tritt chuckled.

He called up one of the digital files that would be included in the NFT packages: an interactive three-dimensional scan of a painting. Scrolling through the topological rendering of the canvas, Tritt compared the experience to being in a “virtual gallery.” Brick-and-mortar galleries would have to adapt or face irrelevance, he projected—“the value is in digital assets.” Onscreen, we tumbled around the painting, zooming into the tiny ridges of brush strokes. The simulation was vaguely reminiscent of a virtual real estate walkthrough, the kind that had proliferated during the pandemic. Other elements of the NFT grab-bag would cover different digital formats, Tritt said: “a visualization of the artistic process” in the form of code from the printer’s software; and time-lapse footage of the painter’s side of the work, taken from the warehouse’s camera setup, provided the artist was comfortable with having their working experience immortalized on a hard drive.

When we first met, Tritt had been emphatic about not identifying as any sort of tech aficionado. Mentioning Elon Musk’s dorm-room provocation that “human beings are underrated,” he spoke of being “self-conscious” in the presence of robots: “I realize just how complex the simple motor movements that we take for granted are.” That appreciation for the unique, unreproducible nature of human motions was woven into Artmatr's work, Tritt said. “When you make a brush mark, it gives you a physical history of the creation.” The printers then tell a version of that story, arguably more exhaustively. Tritt referred to that as the “fourth dimension” of a work—“how things move through time.” Now, as he scrolled through the painting, I wondered if Tritt’s entry into the NFT space was an attempt to probe that dimension more deeply—or just to make more money off of it.

However much he is accepting tech as a necessary collaborator and door-opener, Tritt remains uncompelled by artificial intelligence. Bristling at the notion that the Artmatr team was “teaching” the printers to paint so that they might one day produce work without an artist, he explained his allegiance to extended intelligence—which envisions machines augmenting and aiding human work, not replacing it. If anything, Artmatr's new phase would allow them to find and platform even more singular artists, Tritt said. Comparing the current generation—my own, in fact—of artists and “creators” raised on and adept at CGI and video games, to picture-takers who found their passions (and the market) opened up by the iPhone, Tritt enthused about doing for art what Apple had done for photography. Through their software and hardware, Artmatr might “extract” an idea from the mind of, say, a teenager who had never painted before. And once the painting was complete, they would be able to avoid the often arbitrary, always heavily-networked gallery world altogether, and take the work straight to the people—by which he meant online.

One of Artmatr's printer extensions, a robotic painting arm, was recently on display at a Sotheby's auction for a piece of NFT art created in collaboration with artist Raghava KK. Photograph by Campbell Silverstein

Hearing him speak of Artmatr's place in an alternative, more accessible online art market, I asked Tritt if their new strategy was a departure from his previous hopes for levelling the painting field. He insisted it was the opposite—in order to be sustainable, true democratization required a robust foundation for production. As an example, he provided Apple’s music-creation software GarageBand, which put thousands of software instruments and an easily navigable interface in the hands of nonprofessional musicians. In order to complete the final step—bringing business into those home studios—the app needed a platform like YouTube, for creators to share their work far and wide. Artmatr had followed a similar trajectory, innovating a technology before latching onto a growing platform to circulate its products. It was a better path, Tritt said—not just because they had done the hard part first, but because it had prompted him to appreciate the abilities and adaptability of human hands and minds to an even greater degree. If a teenager could paint something beautiful without a brush, he wondered, why use one? The human has become the brush—and in the process, Tritt believes, gotten closer to the work than ever before. In the process, Tritt concluded, those young artists might well “create the most beautiful things ever made.” He paused, glancing toward the printer whirring sleepily behind me, then finished: “I truly believe that.”

I was pulling the warehouse’s front door open when I remembered why I had come to Red Hook in the first place—to pick up my painting. Back inside, Jeff Leonard rifled through a stack of completed artworks leaning against the wall near the printer, possibly waiting to be picked up by their creators. Providing a few identifying traits, I waited until he found the bathroom portrait. “I remember this one,” Leonard said, holding the canvas at a distance as Tritt and Jarvis looked on. “It’s nice.” When I arrived, the men had been calmly discussing the big-name artist who was set to tour the studio the next day. With their direction now firmly established, they were confident—not only about their ability to entice even more high-profile artists, but to raise more money. Their focus on NFTs, Jarvis told me, had become “the glue,” creating “more alignment” between Artmatr and the venture capital firms they were speaking to about their next round of funding.. With years of research and development behind them, “we’re not parachuting in” with only a startup idea and no plan, he promised.

The finished painting.

The room was quiet, punctuated only by the sounds of Leonard wrapping the painting up for my commute. I left the men in the warehouse and hopped a train home, where the paper-sheathed canvas drew a few stares. I still had yet to get a clear look at it in person, and despite Leonard and Tritt’s praise, I suspected I could have done better—although at what, I was not entirely sure. And the machine had done exactly what it had been told to do. Possibly I was feeling inside the strange space between holding a painting of your own, and holding one of someone else’s that you had just acquired—both situations with which I had no prior experience. I was trying to decide if the canvas would feel like my own once I peeled it out of its wrapping, when I remembered something else Tritt had said to me two months earlier, as I had looked at the finished piece drying atop the work table. Clocking my speechlessness, he grinned into the camera: “You’re a painter now.”

.jpg)