Hi! Dan here—a few weeks ago I wrote a post called What is underneath productivity? where I argued that if we truly want to understand productivity we have to understand the things that lie below it: psychology, neuroscience, literature, and philosophy. In essence, to look at productivity is to look at the human experience. How our brains and bodies work, and how they can move us closer or further away from what we value.

Once you're thinking about brains and bodies, the next and most important topic to explore is mental health. That's why I'm so proud to share this article with you from Brie Wolfson, a writer who's worked for Figma, Stripe Press, and elsewhere, and now runs the zine for organizational development, The Kool-Aid Factory. It's an honest, and brave account of her struggle with depression, and the tools and systems she built, with support, to help herself cope with it. I think you'll find ideas in it to help you manage your emotional life, and, hopefully a sense of connection with another human who is struggling, and learning, and developing just like the rest of us.

Just over a year ago, I was hit with my first and nasty—and I mean nasty—wave of depression. I made it thirty-two whole years without experiencing a crushing inability to get out of bed or a persistent lump in the back of the throat and it was terrifying to find myself facing some very big, and very scary feelings without any familiarity, experience, or tools to deal with them.

I was so accustomed to being on top of it all. Straight A’s. All American athlete. Two-time novelist. A decade-long career in tech working with many of the smartest, kindest, hardest-working people I’ve ever encountered. And now it could barely muster the motivation to brush my teeth?

I’m on the other side of it now. And, from this admittedly fortunate position, I can say with confidence that I’m grateful I went through it. Having my back against the wall forced me to understand more about what makes me tick, shuts me down, and picks me up. And it forced me to make some big changes in my life to get acquainted with and comfortable accommodating them. I wish I had done a lot of this work sooner.

Given what I now intimately understand about depression, it feels strange to write those words and even stranger to publish them where anyone might encounter them. Depression is awful. I don’t wish it on anyone. I know not everyone finds their way out and that those who do have walked many different paths to get there.

I’m going to share more about the path I walked, and what I learned about myself in the process. I know that I am only one person with one set of experiences and one body with one brain and one endocrine system governing it all. But maybe, just maybe, someone else will find what I tried and learned useful. And maybe, just maybe, someone somewhere will find greener grass, whether their current patch is experiencing rain or shine.

Going upside down

My depression came on a few months into the pandemic when the uncertainty of it all was at its height. I had just broken up with my boyfriend of five years and was living alone for the first time. The solitude was taking its toll. Friends and family were feeling further away every day. People I loved and respected were recommending books and movies they were sure I’d enjoy from my couch, but nothing could hold my attention. My inner world felt completely topsy-turvy.

It didn’t take long for my outward behavior to start reflecting that chaotic feeling inside. Seemingly out of nowhere, I would suddenly have to turn my camera off in meetings. I would flake on plans and eject from phone calls without warning. You can imagine what havoc this would wrap on my life, my work, and my relationships. This kickstarted what turned into a cycle of guilt, anxiety, instability, shame, and frustration. But, I just kept plodding along like nothing was happening.

It took me choking up in response to a cheery woman on the other end of a customer support line asking “how can I help you?” for me to consider that things might be more than a little off. I ended up hanging up after she asked for my order confirmation because the thought of opening up my inbox at that particular moment felt too overwhelming. One time I was out for a run in Marin and I had to sit down in the middle of the trail. It was more than 30 minutes before I was able to stand back up. Not long after that, I found myself in my garage with the ignition on hesitating to open the garage door. That scared me. Enough to know I needed to intervene.

What the heck is going on?

By this time, I barely recognized myself. I felt like I had become an entirely different person who I had no familiarity with. So, I decided to study her. The hope was that by getting better acquainted with the nature of these new feelings, and the person embodying them, I could better manage them all—avoid the triggers, run towards the good stuff, and maybe even more.

I cannot say with any certainty what compelled me to pursue this direction. One hypothesis is that I’m naturally a relatively obsessive documenter. I’ve always felt at home in trackers and dashboards and metrics and lists and everything in between (I expect this might resonate with many readers of this particular publication). Another hypothesis is that I was desperate to create some semblance of order and control in my life. I definitely could not control the dizzying waves of sadness washing over me, but I knew that I could create a kick-ass tracker to help me get smarter about them.

I also think it’s relevant that I was already coming from a place of wanting to bring more self-inquiry into my life. I had been in therapy for about a year at this point and was starting to see glimmers of the benefits. Having a professional on the case and in my corner was not a silver bullet by any means, but it was a meaningful safety net. Even outside of the scope of my depression, working with a good therapist whom I trust has had the most influence on my overall happiness of anything I’ve done in my life. It is an enormous privilege to have the time and money to spend on it.

So, alongside my work in therapy, I committed to a month of tracking my moods on both a proactive and reactive basis (though three weeks turned out to be enough).

My Reactive Tracking System took the form of a log of times I felt the sad wave. I logged the intensity of my sadness on a five-point scale and recorded the time, place, what I was doing, who I was doing it with, what was on my mind, and anything else that felt relevant. (I landed on five because I wanted to capture sufficient nuance without diluting the data.) I also made sure to log what I was doing in the hour before bed and in the hour after I woke up every day. My morning log always included a best estimate of how much sleep I got according to my Apple Watch. Over time I also included my own impressions of sleep quality (ie. how tired did I feel when I woke up?).

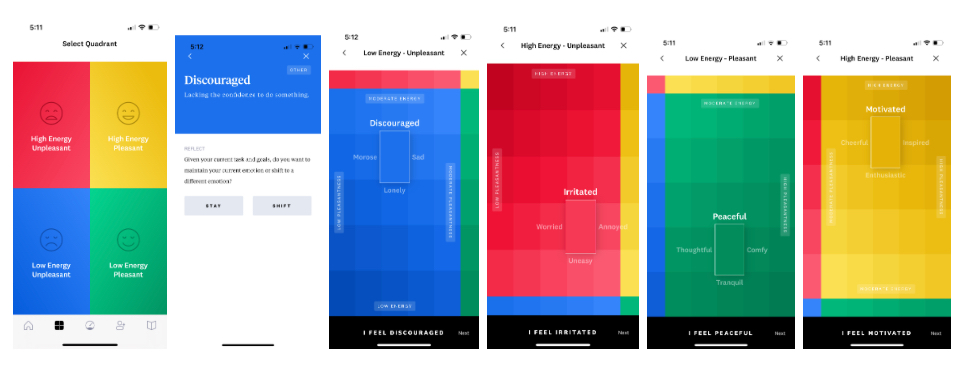

My Proactive Tracking System took the form of a system of randomized prompts to log my mood throughout the day. I used Yapp Reminders to send the prompt and Mood Meter (screenshots below) to log my moods. Of all the apps, I like this one best because I like the words it employs to capture the nuance of how I was feeling (versus a simpler rating scale). One cool thing about the app is that it also asks you if you want to maintain or shift your mood. This became a helpful data point.

What I learned

It sounds like a lot of work, and it was, but here are the kinds of insights I gleaned over those three weeks. They are very specific to me, but I thought it might be helpful to share the kind of stuff I was able to learn about myself. Most of it wasn’t obvious before I started all this tracking. And, many of these things remain true in my healthier place.

- Having to do something unexpectedly was extremely overwhelming: Changes of plans, Slack pings, random little chores cropping up, even phone calls from loved ones usually caused a swirl. Unsurprisingly, work was the source of the majority of these.

- If I had a bad morning, I was probably going to have a bad day: If I was sad early in the day, I was much more likely to have more sad moments later in the day. I started many days opening up work email/Slack in bed. Ick.

- Chatting on dating apps was surprisingly fulfilling: People were really kind and it was a fun way to talk to strangers, especially when that wasn’t possible IRL.

- Drinking wasn’t helpful in the moment, and was harmful the next day: I’m not a big drinker, but for some reason had subscribed to the “I’ll have one drink to wind down” thing. Turns out, it doesn’t work for me at all. And it reduces my sleep quality, which makes me crankier the next day.

- I eat meals at weird hours: Without the constraints of when other people were eating meals, I found myself on my own schedule.

- I was doing a lot of online shopping: Like, a lot.

- I was doing a lot of scrolling on Netflix: Sometimes I’d just scroll and not watch anything. For hours.

- A run with a view was very healing: My standard run around Golden Gate Park was good, but a trail run up to a vista was really, really good.

- Seeing friends could go either way: In some cases, it would initiate a spiral of anxiety and in others would be a huge boost to my mood. There were a small handful of friendships that I was surprised to learn were a very bad fit while I was experiencing depression. There was another small handful of friends that were particularly good. I did a lot of introspection and work with my therapist on this topic over this period.

- Working out and time outside guaranteed a mood boost: The days where I moved my body a lot and/or spent extended periods of time outdoors were infinitely better.

- Sleep was a huge indicator of how I felt: And I was guaranteed to have a better night’s sleep if I did a hard workout.

In hindsight, it’s pretty surprising that I was able to keep the tracking up despite feeling so unmotivated and overwhelmed in other areas of my life. I think what kept me going was having one space, however small, where I made all the rules and controlled all the outcomes. While everything else made me feel helpless and powerless, my tracker made me feel safe and cozy—productive even. (This theme comes back later.)

Good Day Cheat Codes

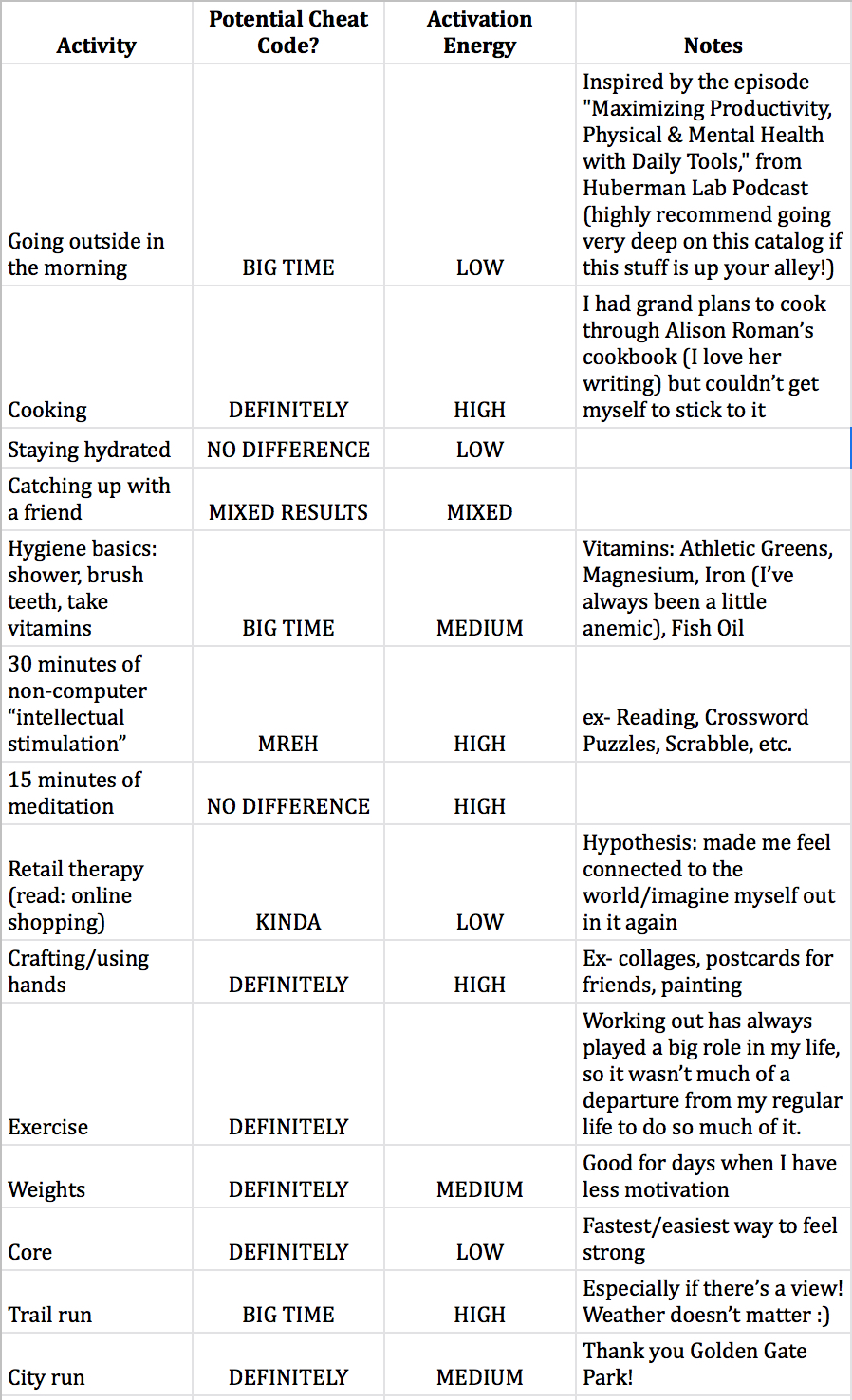

The insights about my moods inspired another experiment. The goal of this one was to determine whether any activity would make a good day more likely. Or better yet, guarantee one. After doing a bit of research with friends and on the internet, I sat down and made a list of Good Day Cheat Code candidates.

I committed to doing the activity for three days in a row before evaluating its candidacy. I relied on a combination of data from my mood trackers and my anecdotal feeling to evaluate whether something improved my day or not. I also tracked the activation energy required to do the thing as a proxy for how likely I was to actually do it.

I’ll admit to running a very shoddy experiment. A reasonable person would say that I didn’t have a real baseline/control group, or experiment over enough time, and that correlation and causation would be completely indistinguishable. But I wanted insights fast, and whether they were real or imagined, I figured it probably wasn’t going to hurt. And plus, all the tracking was still helping me access itty bitty flashes of warm-and-fuzzy feelings.

I’m sharing that list and where I netted out in case it can be a resource for others. I still use these insights to create good days.

Other activities I was curious about but never got around to trying:- Glucose Tracker

- Breathwork

- Sound baths

- Acupuncture

- Cupping

- Antidepressants

- Eight Sleep Mattress

Time To Get Happy

Even though I was learning a lot more about myself, I was still centimeters away from crying at any moment. And boy oh boy was I sick of crying. I felt like I collected enough information to start taking some well-informed action.

First, plugging the holes

It had become fairly obvious that there were two big changes I would probably have to make if I was going to reliably and regularly have a good day.

The first was around work. I knew that:

- The demands of my workload meant that I didn’t have that many hours in the day to dedicate to myself.

- The rigidity of my schedule meant that I couldn’t activate a cheat code when the mood struck, which made me much less likely to do it (for example, if I woke up and wanted to go for a run but had a scheduled meeting, I would take the meeting and skip the run).

- My lack of focus prevented me from doing work I was proud of, which was contributing to a cycle of guilt.

- My mood swings made me an awful colleague, which was contributing to a cycle of guilt.

The second was around a couple of close friendships. The details feel too private to share and would probably be boring anyway, but through careful observation and introspection, I learned that I would have to take time away from those friends in order to properly heal.

As gently and delicately as I could, I told these few friends I needed to take a break. I also quit my job.

I also want to acknowledge the role financial security played in my recovery, specifically with regard to my ability to step away from work when I felt I had to. During this time, I was able to fully prioritize my mental health over everything else. This means that I could focus on my well-being without worrying about the financial impact of my strategies or coping mechanisms. I am tremendously privileged to have this option and I know that it is not available to everyone, or even most people. This includes therapy. I have to be honest that I’m not sure I would have been able to realize the full benefits of all this work so quickly, or maybe even at all, without it.

Still, these were extremely difficult decisions and conversations. I was terrified of further distancing myself from my community at a time that I was already feeling so isolated. I was terrified of doing irreparable damage to my professional reputation. If I felt like I could squeak by without taking these objectively-harmful-to-people-I-loved-and-respected actions, I would have. But I knew I had to prioritize my recovery and that these were decisive steps in a direction I needed to go. And, as a Good Metrics-Driven Decision-Maker™, I had high confidence in taking these specific steps.

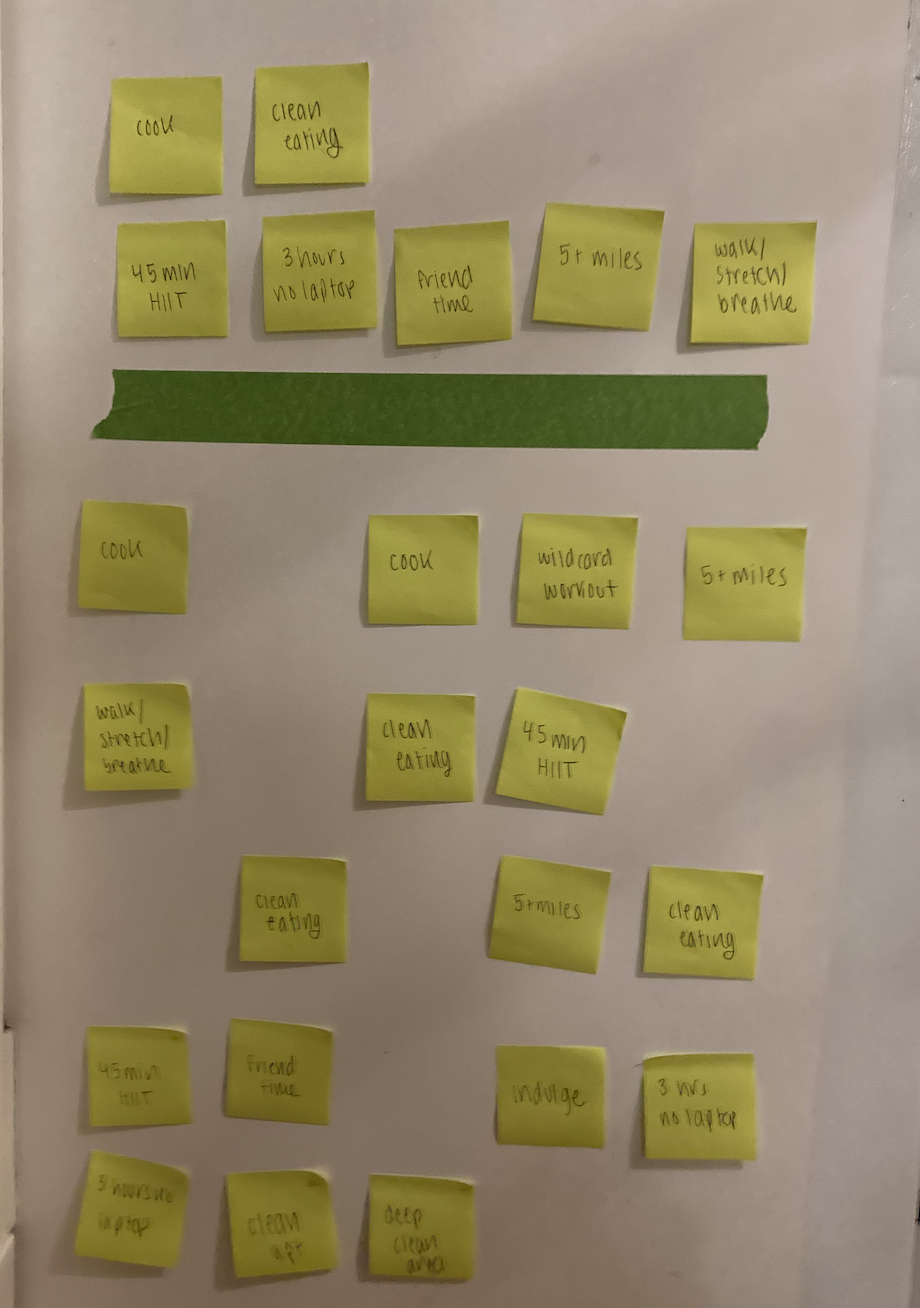

Then, activating my cheat codes: The Post-It Method

To introduce some structure into my now very empty days, and armed with the insights into what made me happy, I invented The Post-It Method. This entailed writing any Good Day Cheat Code onto a Post-It. The only rule for what went onto one was that I had to be able to do it right now.

Initially, the Post-Its had very basic tasks like ‘shower’ or ‘brush teeth’ or ‘go outside.’ In low moments, I could go to the wall and pick something and do it immediately to feel a little better—something about not only doing the action, but also moving something above the line felt really good. Even at the time I was aware that it was a low form of “productivity,” but it was forward progress nonetheless. And at that time, small moves and a little momentum made a huge difference.

Over time, I got more and more Post-Its over the line more and more consistently. I introduced more substantive and increasingly engaging tasks like hiking, writing, reading, or cooking. After about a month, I was able to go onto a weekly cadence, which is what you see a picture of below.

It worked!

Eventually, I was able to ditch the Post-Its altogether. There are, of course, still little bumps and paper cuts in my life, but they don’t rattle me as much. Now that I know what it’s like to have none, I don’t take my happiness for granted, which ironically makes me happier. On top of that, I acquired many tools for dealing with low moments of any shape and size and maximizing the happiness and satisfaction in my life.

On the work side of things, I started doing some research on a topic that I’ve always been interested in simply because learning about it made me happy. That learning turned into conversations with lots of people I admire, which turned into a series of consulting projects. And that turned into a capital J Job that I absolutely love and that pays the bills. I hope I do this work forever, and it looks like I might just get to. In my relationships, most of my friendships are back on track, primarily due to these particular friends being exceedingly and maybe even unreasonably empathetic and kind. Some friendships are not as accepting of change, but I’m at peace with that—I have a new friendship with myself. I know how to cook a few more things and found some incredible running and biking routes across the Bay Area that I still frequent. I’m back to reading and writing a ton and my gusto for TV has been reignited. And on top of all of that good stuff, I’ve also fallen in love.

I got my brain back. And then some.

But...

I really want to end things here—a happy ending! But the words are feeling strange again. I wrote this piece to provide a structure for self-discovery. I wrote it with the hope that it might help someone in a dark place find optimism. Like any well-trained operator, I provided clear tactics and linear steps. Like a good storyteller, I gave you a beginning, middle, and end. But the truth is, there is no stopping point when it comes to mental health. I can still feel the depression lurking. And while this particular section of my narrative may end with a life built back up, I am acutely aware that depression mainly serves to break a person down. And that its most powerful and pernicious feature is that it can shift shapes in such a way that allows it to find anyone, anywhere, at any time.

I am not naive enough to think I’m smarter than my depression or anyone else’s. But I am smarter about what goes on in my own head and heart. And, no matter where we are in this story, I think that’s a pretty cool and useful thing to be smart about.