16. On the themes of language and communication in The Plague

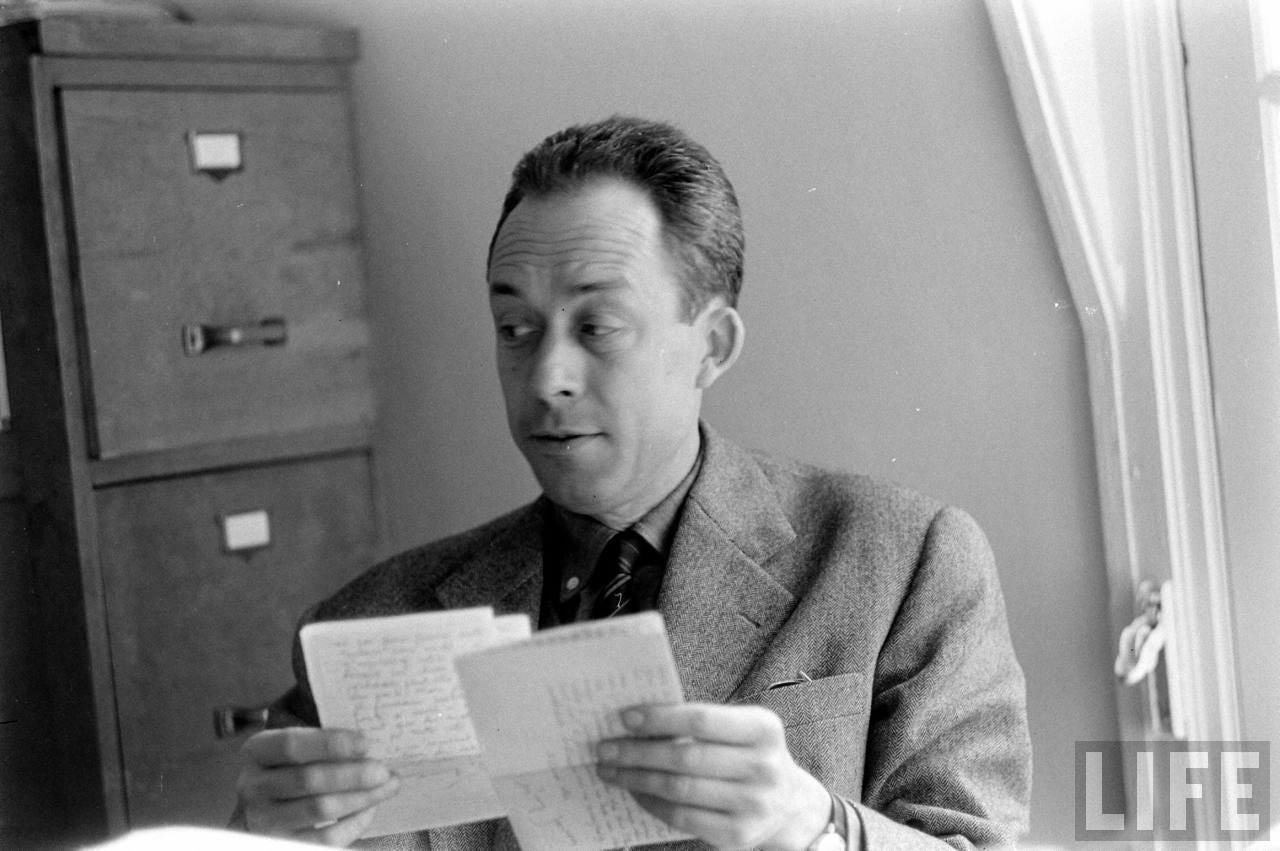

16. On the themes of language and communication in The PlagueAnd the underlying influence of technology in the spread of nihilism and abstraction

1. The theme of illness and disease in The Plague is so overt that it often overshadows what is arguably the equally important themes of language and communication in the novel. In particular, this is enacted in The Plague in terms of the act of writing and the condition of being a writer. Even before the first signs of the plague are introduced, the conditions of writing are brought to the forefront of the novel, the narrator drawing immediate attention to the work as a chronicle, as a written artefact. At the conclusion of the opening chapter, after describing the township of Oran, the narrator interjects with a few observations – what he calls ‘the commentary and precautions of language’ – on the nature of his chronicle, regarding objectivity, his sources of evidence, and his methodology for using materials at hand. Here the narrator draws upon, amongst his own experiences, the writing of others, who also experienced the plague, but from different perspectives. It is interesting to note therefore that almost all the main characters who are introduced in the novel are, in one way or another, writers. After finding the first dead rat in his hotel, Dr Rieux meets Raymond Rambert, a journalist from one of the major Paris daily newspapers. Soon after, the narrator introduces another character, Jean Tarrou. His notebooks are one of the main sources of information about how the plague affected the townspeople in diurnal detail. ‘His notebooks, in any case, offer another chronicle of this difficult period,’ the narrator states: ‘But it’s a very particular chronicle, one that seems biased toward insignificance. At first glance, you might think Tarrou had gone out of his way to examine things and people through the wide end of the binoculars.’ Another character to be introduced at this point is Joseph Grand, one of Rieux’s former patients, and a clerk at the Municipal Office. In due course, it is revealed that Grand is in fact a struggling novelist. Later, the Jesuit priest, Father Paneloux, is introduced. He, too, is a writer, who had ‘already distinguished himself with his frequent contributions to Oran’s Geographical Society Bulletin, where his reproductions of ancient inscriptions made him an authority. But he had gained a wider audience than most specialists by giving a series of lectures on modern individuality.’ Paneloux is also doing research for a book on St Augustine and the African Church. But perhaps the most important character in the novel is Dr Rieux. The narration of events in the city, which lead to the onset of plague, begins with Rieux’s finding the first dead rat. He urges the administration to declare a state of emergency. And he runs the medical side of the operations throughout the epidemic. It does not come as surprise, then, to discover in the final chapter of the novel that Rieux is, in fact, the narrator, the author of the chronicle. But he is distinct from his associates in the chronicle in one respect: although each of these other figures encountered the plague already as writers, there is no indication that prior to plague Riuex was a writer, or was at all interested in writing. But for Rieux, a doctor, after the prolonged ordeal of struggling against the plague, surrounded in his own efforts by the efforts of these other various writers, he finally, through that experience, becomes a writer. If read in parallel with the theme of illness, the theme of writing in The Plague throws some light on Camus himself. We’ve already seen, in describing an earlier period in Camus’ life, how the onset of his own tuberculosis precipitates his development as a writer. Now here, in The Plague, the chronicle of events is framed by the development of a character, Dr Rieux, who, in the process of struggling against illness and restoring health, also becomes a writer. In doing so, he draws on the written works of various other writers: a journalist, a novelist, a scholar (who also lectures for a non-specialist audience), and a writer of miscellaneous notebook entries and sundry observations about diurnal life. In other words, Camus has drawn on his own past and present experiences as a writer, in its various and multiple forms and stages of development. Like Rambert, Camus was also a journalist (in both Algeria and France), and – during the period of writing The Plague – the editor of the French newspaper, Combat. Like Grand, Camus was also a novelist, of an unpublished work, A Happy Death. Like Paneloux, Camus had also written an academic work of St Augustine, his diploma dissertation, Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism (1936), and he also writes for a non-specialist audience, with his two collections of lyrical essays and The Myth of Sisyphus. In Algeria in the late 1930s he also organised and participated in a public lecture series, a practice he continued after the war, as his fame grew – for example, his lecture at Columbia University in 1946. And like Tarrou, Camus (from the age of 22) also kept notebooks in which he also made observations ‘biased toward insignificance’ and ‘had gone out of his way to examine things and people through the wide end of the binoculars.’ Many of Tarrou’s observations, for example, are drawn almost verbatim from Camus’ own notebooks. 2. The themes of language and communication in The Plague are very much grounded in an exploration of the effects of communication technologies. This is itself grounded in a broader, underlying examination of technology generally. For Camus, the growth in technology during the early- and mid- 20th century formally created many of the conditions for abstraction and nihilism – which in turn increased the possibilities for ideology to take hold. This was, particularly during the period he was working on The Plague, a growing concern. He only touched on this notion briefly in The Myth of Sisyphus, in the soliloquy of the Conqueror in the middle part on “The Absurd Man”, which argued that, until then, ‘human beings were created to serve or be served.’ But the Conqueror hints at a change that may be occurring within the current ‘machine age’, which threatens this order. In his 1939 essay on Oran, in detailing the public works along the Algerian coast, Camus provides a more extended description of how technology was quickly outstripping the human and natural scales. ‘Vast landscapes, rocks climbing up to heaven, steep slopes teeming with workmen, animals, ladders, strange machines, cords, pulleys,’ he writes. ‘Man, moreover, is there only to give scale to the inhuman scope of the construction.’ In “The Human Crisis”, however, in 1946, Camus describes, in similar terms to the uses of industrial machinery, the administrative machinery of modern bureaucracy, which equally deploys technology to facilitate nihilism. ‘More and more does contemporary man interpose between himself and nature an abstract and complicated machine which thrusts him into solitude.’ Elsewhere in the same lecture, he describes the impact of this on modern society. ‘In short, we no longer die, love, or kill except by proxy,’ he states. ‘This is what goes by the name, if I am not mistaken, of “good organization”.’ This is an idea he repeats later in “Neither Victims Nor Executioners”, where he writes: ‘Just as we now love one another by telephone and work not on matter but on machines, we kill and are killed by proxy. What is gained in cleanliness is lost in understanding.’ Technology, in other words, underpins and facilitates the ‘age of abstractions’, enabling nihilism from proliferating. This understanding is carried through by Camus into his analysis of abstraction, ideology, and nihilism, in The Rebel. ‘The principal fact is that technology, like science, has reached such a degree of complication that it is not possible for a single man to understand the totality of its principles and applications.’ The human scale is lost; natural limits denied. ‘The political form of society is no longer in question at this level,’ Camus writes, ‘but the beliefs of a technical civilization on which capitalism and socialism are equally dependent.’ Here he references the work of James Burnham, whose notion of the managerial revolution sought to describe the co-ordination between such ideologies and advances in industrial and bureaucratic technologies. But Camus only does so critically, and as a way to introduce the work of Simone Weil, whose posthumous works Camus had been editing for Gallimard, and which had exerted no small influence on his own thinking. ‘It is only fair to point out that this era of technocracy announced by Burnham was described, about twenty years ago, by Simone Weil in a form that can be considered complete, without drawing Burnham’s unacceptable conclusions.’ Here Camus cites Weil directly:

Camus’ argument against technology in The Rebel was rehearsed in an earlier lyrical essay – “Prometheus in the Underworld” – published the same year as The Plague. ‘Prometheus was the hero who loved men enough to give them fire and liberty, technology and art,’ he wrote. ‘Today, mankind needs and cares only for technology.’ As in the rest of The Rebel, however, Camus’ response is not to reject technology outright, but rather to argue for the need to recognise and operate within its limits. ‘The very forces of matter, in their blind advance, impose their own limits,’ he wrote. ‘That is why it is useless to want to reverse the advance of technology. The age of the spinning-wheel is over and the dream of a civilization of artisans is vain. The machine is bad only in the way that it is now employed. Its benefits must be accepted even if its ravages are rejected.’ This is a point also made in his earlier essay on Prometheus: ‘We rebel through our machines, holding art and what art implies as an obstacle and a symbol of slavery. But what characterizes Prometheus is that he cannot separate machines from art.’ 3. In 1939, when Camus first wrote his essay on Oran, which would soon decide the setting for his plague novel, he compared the vast public works along the North African coastline, with its ‘workmen, animals, ladders, strange machines, cords, pulleys,’ as resembling artistic depictions of ‘the building of the Tower of Babel’: a monument to miscommunication and misunderstanding. It is in this context that Camus’ general arguments regarding technology – as tools of abstraction and nihilism – appear in The Plague, in terms of the role of communications technology. The telephone, for example, is introduced, prior to the onset of plague, as an instrument of business and commerce: ‘a whole population is on the telephone or in cafés, talking about bank drafts, bills of lading, or discounts.’ When the plague arrives, the telephone becomes one of the ways to virtually escape the town, to breach its walls. ‘Inter-city communication by telephone,’ the narrator states, ‘which was permitted at the start, put such a strain on public booths and on the phone lines that they were completely suspended for several days before being severely limited to what were called urgent cases, like deaths, births, and marriages.’ As the plague progressed, however, the telephone became a more ominous sign of potential death. When Rieux visited a house, to determine whether or not it contained plague victims, it was with a telephone call that he then set the whole administrative process in motion. Each call brought police and ambulance, to separate families, inter some in isolation camps, others to hospital. It was a cablegram that officially announced the plague. ‘The cable read: “Declare a state of plague. Close the city.”’ After the telephone, cablegrams and telegrams become the dominant means of communication, but this only acted to diminish language further.

For Rieux, for example, it was via telegram that he maintained contact with his wife, who was outside the town, in a sanatorium, where her tuberculosis was being treated. It was via telegram that she downplayed her worsening condition – and it was via telegram that he was notified of her death. Some in the town continued to write letters, but this quickly became an absurd act, because mail was not allowed to officially enter or leave the town – the paper could carry the bacillus. There were unofficial means of attempting to get a letter out, but as no answer could ever be received, it was unclear which letters succeeded in getting through and which didn’t. But some kept at the habit of writing, even if it became separated from an act of communication.

Finally, there was the radio. In the early days, the Ransdoc Agency, which operated on the local radio station, began its sessions by announcing the number of rats that had been collected and burned each day. But the radio, too, quickly became an instrument of absurdity.

In this way, Camus described in The Plague what he had referred to elsewhere as loving, dying, or being killed, by proxy. In other words, the use of communications technology as a form of living by proxy. 4. From the beginning of the novel this point and counterpoint, of abstraction and the struggle against abstraction, can be read playing out through various mid-century communications technologies – telephone, telegram, and radio – and various forms of writing, embodied in the main figures which populate the novel. In relation to writing, the struggle against abstraction is the struggle to overcome the impediments to the restoration of communication between individuals. In relation to the plague itself, which, as Camus argued, makes one ‘lose one’s flesh’, the struggle against abstraction is the struggle to return thought to the body, to reacquaint individuals with the physical aspect of their being. Mediating between these two themes of illness and writing in the novel, the interplay of one with the other, is a concern with forging a style of writing, and, more importantly, an attitude toward communication, which will diminish its tendency toward abstraction, and secure its relationship to the body and the natural world. It is this concern which structures the narrator’s decision to attempt his plague chronicle. But the tendencies for such communication technologies to promote abstraction and distance rather than to overcome either one is a situation that predated the plague, and it is one that threatened to return when the plague subsided and the gates reopened. It is perhaps with a bitter note that the narrator describes how the opening of the gates was accompanied by the resurgence of various communications and bureaucratic technologies, like the opening of Pandora’s box. ‘At dawn one fine February morning, the gates of the city finally opened,’ the narrator states, ‘hailed by the people, the newspapers, the radio, and the announcements from the prefecture.’ Next week we will examine a particular form of writing that came to influence The Plague – the role of journalism in Camus’ thinking, 1938-1946. If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: please consider signing up to this newsletter (or updating to a paid subscription). And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

You’re a free subscriber to Public Things Newsletter. For the full experience, become a paid subscriber. |

Older messages

On the restoration of communication as a form of rebellion in Albert Camus’ thought

Monday, November 15, 2021

Or, how the play The Misunderstanding (1944) was a rehearsal for The Plague (1947)

14. On the transposition of The Myth of Sisyphus into an argument about language

Monday, November 8, 2021

Or, the influence of Brice Parain's philosophy of expression on Albert Camus

13. On the resistance to nihilism, abstraction, and ideology in The Plague

Monday, November 1, 2021

Or, how Albert Camus' novel implicates us all

12. On Camus’ outline for a politics of non-violence and non-domination

Monday, October 25, 2021

Or, how Camus' ecological imagination resists nihilism and ideology

10. On the ecological imagination of Albert Camus

Tuesday, October 19, 2021

From 'Don Juan Faust' to Euphorion

You Might Also Like

Red Hot And Red

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

What Do You Think You're Looking At? #204 ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What to Watch For in Trump's Abnormal, Authoritarian Address to Congress

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Trump gives the speech amidst mounting political challenges and sinking poll numbers ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

“Becoming a Poet,” by Susan Browne

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

I was five, / lying facedown on my bed ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Pass the fries

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

— Check out what we Skimm'd for you today March 4, 2025 Subscribe Read in browser But first: what our editors were obsessed with in February Update location or View forecast Quote of the Day "

Kendall Jenner's Sheer Oscars After-Party Gown Stole The Night

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

A perfect risqué fashion moment. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 3.3.2025 Now that award show season has come to an end, it's time to look back at the red carpet trends, especially from last

The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because it Contains an ED Drug

Monday, March 3, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It Contains an ED Drug The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It

10 Ways You're Damaging Your House Without Realizing It

Monday, March 3, 2025

Lenovo Is Showing off Quirky Laptop Prototypes. Don't cause trouble for yourself. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY 10 Ways You're Damaging Your

There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood

Monday, March 3, 2025

Today in style, self, culture, and power. The Cut March 3, 2025 ENCOUNTER There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood A Sex Education fan favorite, she's now breaking into Hollywood on The White Lotus. Get

Kylie's Bedazzled Bra, Doja Cat's Diamond Naked Dress, & Other Oscars Looks

Monday, March 3, 2025

Plus, meet the women choosing petty revenge, your daily horoscope, and more. Mar. 3, 2025 Bustle Daily Rise Above? These Proudly Petty Women Would Rather Fight Back PAYBACK Rise Above? These Proudly

The World’s 50 Best Restaurants is launching a new list

Monday, March 3, 2025

A gunman opened fire into an NYC bar