It took less than 12 months for Sequoia Capital to turn $11 million dollars into $495 million with its investment in YouTube. Interestingly, the investment memo for the deal has, by my estimation, roughly 23 grammatical errors. It is riddled with spelling mistakes, misplaced words, poor punctuation, and mislabeled competitors. Nevertheless, this document’s thesis returned 44x cash-on-cash returns in the space of an NBA season.

When Jack Ma pitched Masayoshi Son in 2000 for an investment in his fledgling ecommerce site Alibaba, “He had no business plan, zero revenue,” Son said in a later interview. “But his eyes were very strong. I could tell from the way he talked, he has charisma, he has leadership.” This is very clearly a stupid investment thesis. Saying you got lost in someone’s eyes and gave them 20 million dollars would cause most limited partners to panic. Despite the dumbness, or perhaps because of it, that investment returned 4,500% when Alibaba went public at a $90B valuation. The stake ballooned up to $150B in value at one point—not bad for simply swimming in the depths of Jack Ma’s irises.

In an even more impressive display of gut-based ROI, throughout my life I had always stated I would take my time when it came to dating. My hypothesis was that you need four seasons, a road trip, and an extended visit with the inlaws before you could make up your mind. Nevertheless, within 90 days of my first date with my partner, I told her I was going to marry her.

Note: Her response was “nice of you to say that” lololol. Took her a bit longer to come around. We tied the knot in less than a year of us being “official.”

When people asked me how I knew she was the one, perhaps expecting me to list off a formula I had made, they were always surprised to hear my answer—I just knew. (What can I say? I have a reputation amongst my friends for being a formula guy.) There was no criteria, no hurdle rate for this choice, which is arguably the most important decision someone can make. It was pure instinct. Something deep within me knew almost immediately that she was it.

When you choose to commit capital, whether fiscal or emotional, into a venture, there is some hope of return. In the context of a business, you want it to grow and return money. In the context of a relationship, you hope it returns many years of happiness. In either case, the return you expect is evaluated along two dimensions of viability. First the level of return that you can expect (how much money, how much happiness, etc) and second is the likelihood of that return actually happening (aka risk/explosive divorce).

Investment analysis is the process by which you try to figure out what the return and risk are and see if you are comfortable with the balance between the two. Here’s where it gets interesting. The more clearly you can link data to available upside, the less return there is going to be. Namely, if there is a stock that somehow everyone knew what the price would be in exactly 10 years, the price would shoot right to that valuation and pretty much stay there until that 10 year mark occurred. The more consensus there is, the smaller the available returns are. With marriage this link between available upside and data isn’t quite analogous to the stock market. I am not advocating the view that there are a bunch of potential spouses out there ignored by everyone that you should marry. My perspective would be that there is no truly 100% predictive data set when it comes to relationships, so you can never fully derisk the decision. At a certain point, you trust your gut and take the leap.

Note: There is an argument to be made that our financial system actually doesn’t do this anymore (e.g. see Tesla, Rivian, etc). The efficient markets hypothesis just doesn't seem to be holding up. In earlier writing, I have argued that this process of our financial system breaking down is a pattern that has occurred since ancient Sumaria and that there are things we can do to be prepared. See here ($)

In a blog post, Marc Andreessen (I can’t seem to quit writing about that beautiful, cantaloupe-headed, internet-browser-inventing bastard) said the following about consensus:

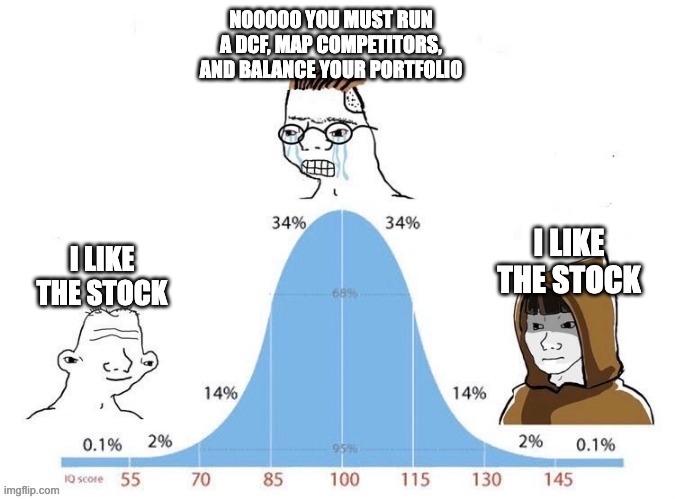

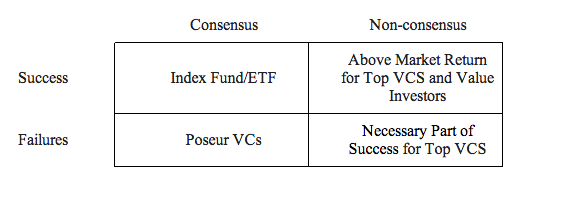

“We think you can draw a 2×2 matrix for venture capital. …And on one axis you could say, consensus versus non-consensus. And on the other axis you can say, successful or failure. And of course, you make all your money on successful and non-consensus.”

He goes on to explain:

“It’s very hard to make money on successful and consensus. Because if something is already consensus then money will have already flooded in and the profit opportunity is gone. And so by definition in venture capital, if you are doing it right, you are continuously investing in things that are non-consensus at the time of investment. And let me translate ‘non-consensus’: in sort of practical terms, it translates to crazy. You are investing in things that look like they are just nuts.”

This idea that things should “look like they are just nuts” means the investment opportunity is one without a lot of obvious signals. The best investments will have founders that don’t look like other founders, build products that have never been tried before, and are just kinda...weird. The obvious signals of revenue growth or customer retention won’t be present. It is in making bets where everyone tells you that you are very wrong that you will do incredibly well… sometimes. Other times you lose all your money, and, if things go really bad, your reputation.

What is difficult is getting to the level of confidence where you can put two middle fingers up to consensus and pull the trigger. To analyze these highest returning investments you either have to discover some novel insight in the existing data set that no one has discovered or you must find something entirely new from somewhere entirely different.

This is why venture is such a fascinating investment class to me, it is the only one where secrets can exist in abundance. Where the weird is celebrated rather than derided. When put in comparison with the public markets, where everyone has fairly similar data sets and often competes on speed/timing of trading versus the inherent value of the company, venture is this little, dark, mysterious realm. One where data is scarce and courage/intuition are rewarded. Note: Tiger Global is arguably changing the game to one of speed for venture.

How to build intuition

So—what does this all mean? What is the connection between venture investing and marriage? The connecting thread of being a great investor, of living a great life, is going forward based on intuition, not analysis. As you cultivate the ability to become a good asset allocator, of course you need to learn the fundamentals (and Napkin Math will continue to go through them! We will do a series on cash flows here soon) but you simultaneously need to cultivate intuition.

Intuition is informed by living, not just learning. You can read all of the great books on investing that you like, but until you start deploying your own money you’ll never learn how to navigate the markets. In parallel, you can read all of Shakespeare’s works and memorize The Notebook but until you start going on dates you’ll never learn what you want in a partner.

If you feel deficient in the area of intuition, I would give two strategies and a warning:

- Become An Apprentice: The quickest way to level up your career is to find the smartest, most senior person you can and latch on. A common saying is that Venture is an Apprenticeship business, one where learning how a deal feels is just as important as how a deal looks. In my own career, I have actively benefited from mentors who know what they are doing and have guided me to better paths.

- Swing for the fences, live for base hits: One of the things that I loved most about living in Silicon Valley (RIP) was the attitude of upside. It was actively celebrated to make stupid risky decisions. If you are talented and get enough at bats, you’ll eventually hit a homer. My career has reflected this. I tore through multiple startups while there, never quite finding the homerun I wanted. It was only on the eve of turning 30 did I find something that I excelled at and was financially lucrative (if you are wondering what that thing is, you’re reading it). The more chances you can give yourself the better. Make sure you are doing it in a way that preserves your physical/emotional health. There are many people I know that burn themselves out and have serious issues down the road from swinging too hard.

- A warning—the thin line: Intuition is only a skip away from delusion. As you deploy resources, be sure to set mental boundaries for yourself. It is easy to allow biases, or visions of grandeur, to convince yourself of something that just isn’t true. Be ruthless with your opportunities. Rely on your mentors to check you as you deploy capital.

In my first job doing business analysis, my boss had a little bat with “So What” written on the side. He would bang it on our desks if we sent investment memos that had no central thesis. He would continually ask us what the “so what” of our argument was. (Super annoying habit, but useful training method.)

The so what of this article is that in our instincts are where the greatest returns are. The less data you require to make an accurate decision, the higher likelihood of outsized returns there is going to be. Cultivating that sense of intuition is life's great work for investors. To build the ability to make quick decisions with little data and have them be right is the highest form of allocation art. Whether personal or professional, how we choose to spend our resources matters—choose wisely.

Till next week,

e

P.S. Thank you for all of the wonderful marriage advice I received from my readers, the response was so overwhelming that I wasn’t able to respond to it all. Know that my wife and I read every email and are grateful for this community of people caring about us :) Our relationship is the best investment either of us have made and we are grateful to folks helping us be wise stewards of what we have created.

Ever wonder how stars like Jay-Z build and keep their wealth? Zack O'Malley Greenburg spent a decade researching such fortunes for Forbes (and authoring books like Empire State of Mind and A-List Angels). Now he's writing the Zogblog—a weekly newsletter on the intersection of music, media and money—and serializing his next book, We Are All Musicians Now, via Substack. Click here to get both for free.