Happened - I will gladly pay you Tuesday...

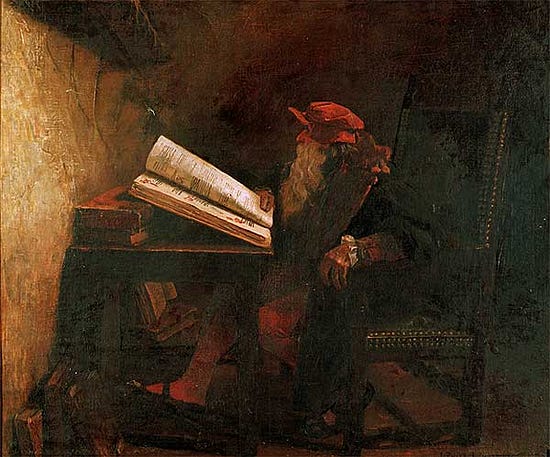

I suspect everybody’s heard the term “Faustian bargain.” It’s a deal where you trade something of long term value but no immediate return — in Faust’s case, his soul — for something that pays off immediately, in the real world. Like pleasure, or power, or money. The thing you trade very often has lasting moral or spiritual value, and the short term gain is very often worldly and fleeting, so the “lesson” of the Faustian bargain, when it finally plays out in the end, is that you shouldn’t trade your morals for money. You shouldn’t sell out, in other words.

Okay, you’re saying, so I’ve heard all this before, but why am I reading it here in Happened, which is supposed to be about things that happened on this day in the past? Well it just so happens that today is the day that Faust: The First Part of the Tragedy, the classic play by Johann Goethe, premiered in 1829. If you’ve ever seen it performed (I bet you haven’t; it’s not performed very often as far as I can tell), it doesn’t follow the normal conventions of the theater. It’s not divided into acts, for one thing; there are just scenes. And I don’t know if it’s because the language is two centuries old, or because it’s been translated from German, but I, at least, find it a bit hard to follow. I mean, take this as an example: If the swift moment I entreat: Tarry a while! You are so fair! Then forge the shackles to my feet, Then I will gladly perish there! Then let them toll the passing-bell, Then of your servitude be free, The clock may stop, its hands fall still, And time be over then for me! That’s Faust speaking to Mephistopheles, making his deal that if the devil can show Faust a “perfect moment” that he sincerely wants to last forever, he can have Faust’s soul in exchange. Now, I don’t know about you, but I just don’t get that whole message from the original passage. It’s like trying to read Joyce’s Ulysses. Sure, if you take a college course about it, and the professor assigns a set of pages each class then at the next class explains what on earth it was that you read, sure, you can get through it (how do I know this?). But try to read it unaided — even after you’ve gotten a blasted A in that very class — and you may find yourself, like me, baffled and annoyed. But despite the difficulty of the 19th-century German original, I think the fundamental Faust story rings true. After all, Goethe didn’t invent Faust; it’s a classic Germanic legend, and it’s based on an actual person: Johann Faust, who lived from 1480 to 1540. The real-life Faust is said to have made a deal with the devil at a crossroads (where have you heard that before?), but instead of great skill at blues guitar playing he wanted unlimited knowledge and earthly delights. He chose human, or short-term values over spiritual, or long-term concerns, and that led to his ruin. In the myths, at least. Boiled down and stripped out of its framework as a religious morality play, a Faustian bargain is the kind of thing people face in reduced form all the time. In fact, let’s have a look at some of the things that have happened on January 19 as versions of that very bargain, or illustrations of it. What if there’s a plague, and you and your friends quarantine together in a fancy hall.One aspect of Faustian bargains is that you can always rely on them as the basis of a good story. Let’s say you’re hiding behind a wall because you committed a crime, and you’re getting away with it. But then you begin to worry that the beating of your heart is so loud, because you’re so keyed up, that your pursuers are going to hear it and find you. And that short-term worry, rather than the actual sound you’re worried about, leads to your discovery. Or what if there’s a plague, and you and your friends quarantine together in a fancy hall where you’ve socked away some primo party supplies, and…well, you can probably see where I’m going with this. And you’re right; my first exhibit in the Faustian nature of January 19 is Edgar Allen Poe himself, whose stories are much more fun to read than Faust (or Ulysses). He was born today in 1809. Which is doubly interesting, because although Goethe’s Faust was first performed on this day in 1829, it was first published in 1808, just the year before Poe was born. And just a year before that, in 1808, Robert E. Lee was born on January 19. Now there’s a guy who made a difficult bargain. He was top of his class at the US Military Academy in West Point, had an exceptional record as a military commander, and became superintendent of that same academy. He wanted the United States to remain intact…and yet he decided to accept command of the Confederate military after those states tried to secede from the US. Since then he’s mostly remembered in the southern states as a cultural icon, but he probably didn’t want any part of that. He was against slavery and against secession, but he’s remembered as a champion of those very things. As for other Faustian events on January 19, how about services put together with the best intentions, but turned against those intentions to become destructive? A postal service is supposed to be a good thing, delivering everything from letters to reports to commercial transactions to gifts. But it was January 19, 1764 that (possibly) the world’s first mail bomb was reported in a diary entry by a Danish historian: “Colonel Poulsen residing at Børglum Abbey was sent by mail a box. When he opens it, therein is to be found gunpowder and a firelock which sets fire unto it, so he became very injured.” Or take airships, some of the first of which were Zeppelins. They offered faster transportation that was safe (at least as far as they knew at the time) and efficient. And then on January 19, 1915, German Zeppelins were used to bomb Great Yarmouth and King’s Lynn in England — the first arial bombardment of civilian targets. And hasn’t that been repeated ad nauseam ever since. “Attractive” but with consequences, or “convenient” but deadly.But a Faustian bargain doesn’t necessarily have to be fatal, or even injurious. How many of the aspects of modern life can be taken in two different ways, maybe as “attractive” but with consequences, or “convenient” but deadly? For one of them, how do you feel about neon lights, which are mostly used in advertising? They can be fun to see, I suppose, but after the first, I dunno, ten thousand? maybe they start to seem like nothing but eyesores. Well welcome to January 19, 1915; the first neon lights for advertising were patented that very day. Some people probably really enjoy neon lights. They have their downsides, but they’re not malicious. But I’ll assume, since you’re reading this, that you have a computer, and if you have a computer, you’ve heard of computer malware and viruses. The people who originally created computers (and networks and communication protocols) were genuinely good folk who probably didn’t even think of the possibility that their inventions could be used for harm. But on January 19, 1986 the first computer virus designed for the soon-to-be ubiquitous IBM PC and its clones was released. It was called Brain, and it comes with a Faustian deal of its own. Brain was written by Amjad and Basit Alvi, two brothers whose goal was to protect the heart monitoring software they’d written from being copied illicitly. Reportedly they were astonished when they started to receive phone calls from around the world about computers infected with the virus they’d intended only for protection. How did everyone get their phone number? They included it in a message displayed by the virus itself. The brothers just didn’t anticipate that the virus would spread completely independently of their medical program. If that’s a set of a couple of nesting Faustian episodes, how about this next one? Adolph Hitler, a guy on very few people’s favorites lists, started pushing the idea of an inexpensive car to be available to the German population, who at the time were still struggling with economic problems stemming from harsh measures imposed after World War I. In 1934, Hitler named Ferdinand Porsche as the lead designer in his “people’s car” project. The result was the Volkswagen Beetle. As most people know, the car was an enormous success. And it involved some Faustian thinking by some of the later purchasers, too. Take a 1960s counterculture member in the US. A VW beetle was the signature car of the movement, and inexpensive to boot — but its origins were in the antithesis of a movement dedicated to peace and love. And the car itself was a mixed bargain — it was still being built in Germany until January 19, 1978 (just in case you were waiting for January 19 to pop up), and by then, compared to more modern designs, it was pretty much a death trap. The thing was flat-out dangerous to you and your family. And yet…it was cheap. And then when the VW executives phased out production in Germany, partly on the basis of the lack of safety, well, they kept production going in other parts of the world (with populations that maybe they didn’t care about quite as much) for another 25 years. That’s my story, and I’m sticking to it. January 19 can be pretty well summed up as a day of Faustian bargains, big and small. Of course, that might not be so different from other days. We’ll just have to wait and see about those. |

Older messages

In which there are birthdays

Tuesday, January 18, 2022

And there might be a camel

A tragic comedy of a day

Monday, January 17, 2022

Or maybe a comic tragedy?

The Ides of January?

Saturday, January 15, 2022

And for that matter, what are "ides" anyway?

Theorem: this story is incomplete

Friday, January 14, 2022

And I can prove it!

In the company of friends

Thursday, January 13, 2022

But, come on, no girls allowed!

You Might Also Like

*This* Is How To Wear Skinny Jeans Like A Fashion Girl In 2025

Wednesday, March 12, 2025

The revival is here. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 3.11.2025 This Is How To Wear Skinny Jeans Like A Fashion Girl In 2025 (Style) This Is How To Wear Skinny Jeans Like A Fashion Girl In 2025 The

The Best Thing: March 11, 2025

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

The Best Thing is our weekly discussion thread where we share the one thing that we read, listened to, watched, did, or otherwise enjoyed recent… ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Most Groundbreaking Beauty Products Of 2025 Are...

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Brands are prioritizing innovation more than ever. The Zoe Report Beauty The Zoe Report 3.11.2025 (Beauty) The 2025 TZR Beauty Groundbreakers Awards (Your New Holy Grail Or Two) The 2025 TZR Beauty

Change Up #Legday With One of These Squat Variations

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE Change Up #Legday With One of These Squat Variations Change Up #Legday With One of These Squat Variations The lower body staple is one of

Kylie Jenner Wore The Spiciest Plunging Crop Top While Kissing Timothée Chalamet

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Plus, Amanda Seyfried opens up about her busy year, your daily horoscope, and more. Mar. 11, 2025 Bustle Daily Amanda Seyfried at the Tory Burch Fall RTW 2025 fashion show as part of New York Fashion

Paris Fashion Week Is Getting Interesting Again

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Today in style, self, culture, and power. The Cut March 11, 2025 PARIS FASHION WEEK Fashion Is Getting Interesting Again Designs at Paris Fashion Week once again reflect the times with new aesthetics,

Your dinner table deserves to be lazier

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

NY delis are serving 'Bird Flu Bailout' sandwiches.

Sophie Thatcher Lets In The Light

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Plus: Chet Hanks reaches new heights on Netflix's 'Running Point.' • Mar. 11, 2025 Up Next Your complete guide to industry-shaping entertainment news, exclusive interviews with A-list

Mastering Circumstance

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

“If a man does not master his circumstances then he is bound to be mastered by them.” ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Don't Fall for This Parking Fee Scam Text 🚨

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

How I Use the 'One in, One Out' Method for My Finances. You're not facing any fines. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY Don't Fall for the