Years ago, I walked into a small café with a wad of cash in my pocket that had taken me six months to save. The café was hosting the art opening for an artist whose work I'd been coveting for years. She was showing a series of smaller more affordable works on paper, at long last, and I planned to leave there with empty pockets and an 18" x 24" smile on my face. I arrived the minute the doors opened, so that I wouldn't have to suffer the heartache of falling in love with a piece that had already been purchased, and—forsaking the wine and cheese table—made a beeline to the back wall.

I stood in front of each charcoal drawing to see which one spoke to me the loudest—something I do by wiping all the thoughts from my mind and simply paying attention to how each one makes me feel. (If it comes down to a few pieces, I'll let my brain take over at that point to talk to me about things like composition, symbolism, or—in cases where I'm buying something from an artist whose career I think might take off in a major way—which piece is most reflective of the artist's overall practice.) On this day, I knew immediately which one was mine.

Overflowing with excitement, I waited in line to talk to the artist—who was surrounded by a gaggle of admirers—to tell her how much I loved her work and to give her the money for my piece. (Isn't that adorable? At that point, I had almost no experience buying art so I assumed that the way to do it was to walk up to the artist during her opening and press a clump of sweaty bills into her hand.)

In overhearing the conversations she was having with the the people ahead of me, it became abundantly clear that she—I don't know how else to say this, please forgive me—was an asshole. Of course, anyone can have a bad day or an awkward exchange, but every interaction I witnessed her having left me with a growing ick. As I got closer and closer to her, the drawing—which I'd already picked out a spot for in my living room—got farther and farther away. By the time there was only one person between us, I no longer wanted it. I knew that every time I looked at it, the only thing I would be able to think about was how I felt in her presence. I walked out, deflated.

In this case, the stakes were low, she wasn’t actively harming anyone, and the only thing I needed to consider was whether or not I wanted to live with her art on my wall. But that experience always reminds me of larger questions.

I think about it whenever there is renewed conversation—usually when an artist is accused of being a horrible person or of doing horrible things—about whether we can separate the art from the artist. On one side of the debate, you have the folks who believe that a work of art is a piece of the artist's soul and, as such, it carries with it the sins (or virtues) of its creator. I completely agree with these people. On the other side, you have the folks who believe that once a work of art has gone into the world, it no longer belongs to the artist but to the people for whom it was made. I also completely agree with these people.

Instead of trying to figure out if we can separate the art from the artist, we might use these opportunities to question the role that art plays in each of our lives. For example, when I was waiting in line at that cafe, I learned that in a situation when I’m acquiring a piece of art to bring into my home, I care very much about the associations I have with the artist as a human being. Those associations are so powerful, in fact, that I've developed a rule: I can only collect work from artists I have a positive or neutral feeling about. If I've already purchased a work from an artist I know nothing about, I won't allow myself to meet them or to talk to them because if I discover that they are unkind, it will dramatically diminish the amount of pleasure I get from their work. But that's just me. And that's just one specific context.

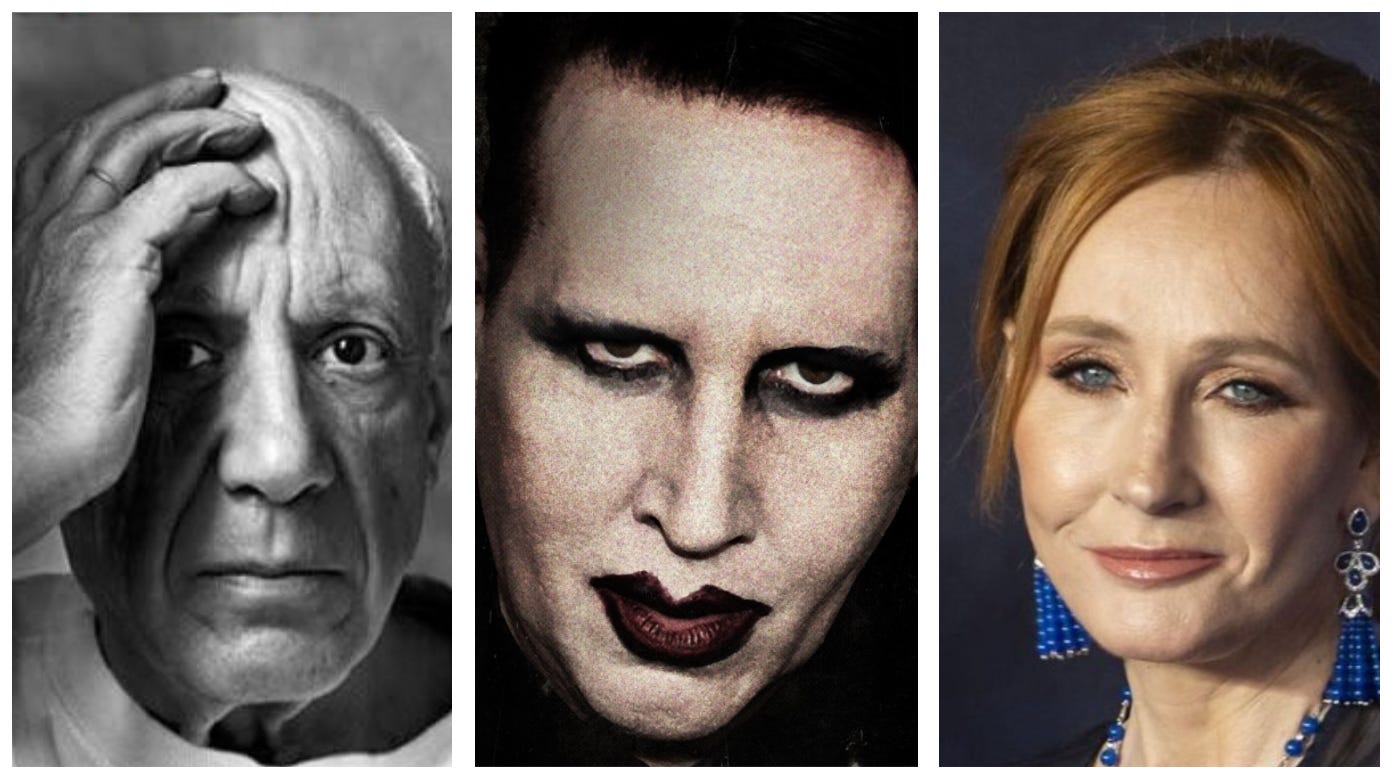

The arrangement isn't so clean when an artist’s work is already woven into the fabric of our lives. What do we do when we find out that a comedian who has given us the solace of laughter likes to drug and rape women? When a musician whose music provided the soundtrack to our childhood gets accused of pedophilia? Or when we discover that an author who has built new worlds for us to inhabit in our imaginations is a hateful bigot? We can’t surgically remove them from our lives, because their work is already a part of who we are, integrated into our bodies and memory, both individual and collective.

If we allow ourselves to be truly open to these questions—if we really want to understand our relationship to artists and what they create—we also have to be open to the vexing, hypocritical, contradictory, and complicated answers that are waiting for us as we consider both our personal experience as well as our responsibility to one another. I’ll go first:

The Cosby Show was my favorite television show of all time, full stop. Not one of my favorites. My favorite. And not just as a kid, but as an adult. I’ve rewatched it so many times that I could sketch a Gordon Gartrell shirt for you from memory and probably beat you at pétanque even though I’ve never played before. I remember, at twelve years old, watching the sequence in which Cliff brings out three birthday cakes for Claire, to try to tempt her, and thinking it was the most beautiful and graceful thing I’d ever seen. The scene was five minutes long and had no dialogue. Mind you, this was a network sitcom in the 80s. Five minutes, of a 24-minute episode, with no talking. No one had ever done anything like that before. I felt about it the way I feel when I see a ballet or listen to the symphony. And, now that we know what we know, I will never be able to watch an episode of that show again. Or perhaps it is more honest to say that I will never be able to enjoy an episode of that show ever again. I’ve tried, and it simply isn’t possible for me. But I wish it were, and I don’t judge anyone who can, especially because there are so many other incredible actors on that show who deserve to have their work and creative legacies cherished.

Similarly, Michael Jackson was my favorite artist. I wore shirts and pins with his face on them. I knew every lyric to every song. I was watching him on TV when he moonwalked for the first time, the day after my seventh birthday. I practiced moonwalking for days after that until I’d figured it out. He’s the only public figure I’ve ever written a fan letter too. So, you’d think that the allegations of pedophilia and rape (which I absolutely believe) would make it such that I can’t enjoy his music anymore. Except that I can, which I find infuriating and difficult to reconcile. Why is this different from my relationship to my favorite TV show? I’ve sat with this quite a bit and what I’ve come to is that when I excise The Cosby Show from my life, nothing else gets taken along with it because I associate it only with itself. Michael Jackson’s music, on the other hand, is far more tangled with other things. To remove it would be to remove all the nights I spent sleeping under his poster in my best friend Katie’s bedroom and the German lullabies that her mom, Petra, sang to us to get us to sleep. It would take with it the memory of Katie and me curled up on my parents bed waiting for the premier of the Thriller video. It would take part of Katie with it, and that’s not something I can bare to lose.

I’ve read most of the Harry Potter books and watched all of the movies many, many, many times. They are comfort, immersion, escape. And, for these reasons, they have grown in importance to me during the pandemic, even though it has come to all of our attention that J.K. Rowling is a reprehensible transphobe. Would I ever purchase one of her books again? Not under any circumstance. Not because I wouldn’t enjoy them—I believe I could—but because she doesn’t deserve a cent from me (this is another convoluted piece of logic that ties into streaming Michael Jackson’s music: that he isn’t profiting off of my enjoyment of his work).

For me, and perhaps for you, it isn’t as simple as whether or not I can separate an artist from their work. There are so many things to consider: when the work came into my life, what else (or who else) it’s attached to, and whether or not my financial support of the work adds to the artist’s power or wealth (and therefore their potential to cause more harm). But, to that last point, what about a situation in which consuming a piece of art gives money to an artist who has done terrible things but saves the life of the person who is paying for it? How do we place more value on one or the other?

Whenever this issue recaptures the attention of the masses—right now we’re in the thick of Johnny Depp and Marilyn Manson legal battles—I steel myself for the opinion pieces that will come out on one side of the argument or the other, insisting that the matter is black or white. Yes or no. Red light, green light. But the reason that people feel so strongly on both sides is because of how strongly they feel about the place that art occupies in their lives. We would do well to remind each other of the power of art to shape society, the multifaceted nature of the issue, and of the exquisitely personal nature of our relationships to art and artists both. When their impacts are as far-reaching and complex as they are, we must reject the notion that any conversation about them will be easy or simple.