Wings of Fire - The Forgotten Tradition of Jauhar

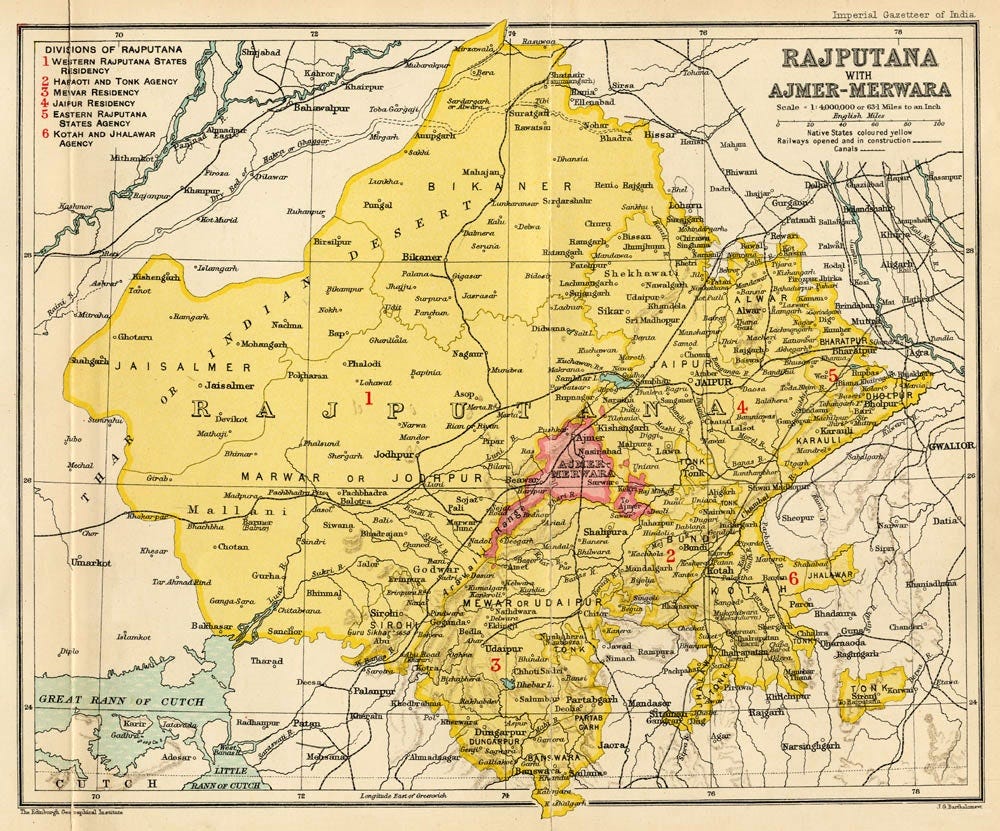

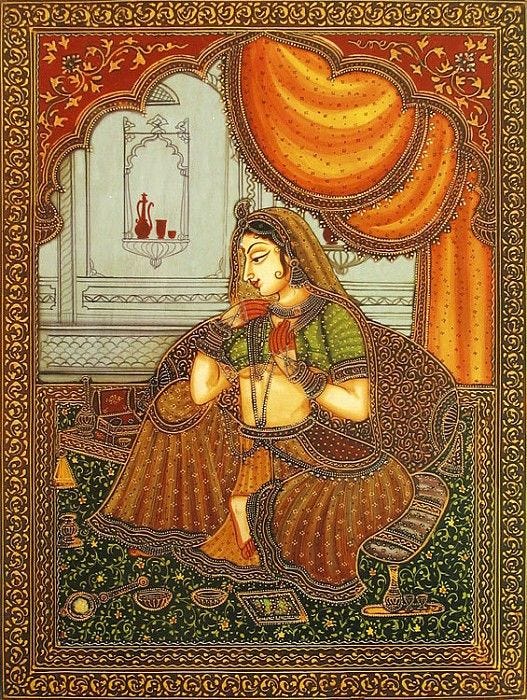

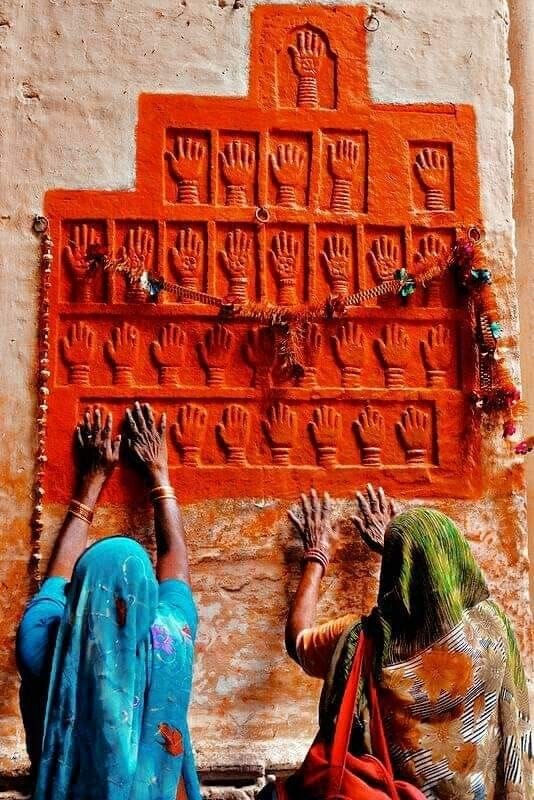

Today’s pickings Wings of Fire - The Forgotten Tradition of JauharThe 12th-century Mass Self-Immolation Practiced by Rajput WomenWars create fractals of a broken world, one within the other, like a house of mirrors. It creates a never-ending loop of atrocities looking onto itself for eternity. However, hidden within those obscure echos of the dark past, the stories of devotion, sacrifice, and bravery slowly reclaim the world. Medieval India was raided frequently by cruel invaders from different parts of the world who tried to bend the law of the land which belonged to the indigenous clans. A land of spirituality and peace, the Indian subcontinent seemed like easy prey for the cruel conquerors both from the east and west. However, every time the darkness blanketed the future, brave heroes awakened to protect the motherland. This might paint a vivid image in your mind of armed warriors. But, not all heroes were men, and not all wars were fought on the battlefield. In the ancient world, considering the traditional gender roles, women rarely had the privilege to learn fighting skills. With the enemies at their threshold, the wars these women used to fight were the ideological ones, and such wars, they often won. Today, I am going to narrate a story of one such war fought based on ideologies. The Indian subcontinent is a unique landmass protected by the Himalayas in the North, and the Indian Ocean in the south, the South-East, and South-West regions are ocean-bound by the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal respectively. The only landlocked region easily accessible from outside the subcontinent is the Northwest region. Therefore, the North-West used to be constantly under threat of invasion. The land needed ferocious warriors to fend off the invaders, and that was the origin story of the warrior clan of Rajputs. The kingdom of Rajputana, which comprises the modern-day Rajasthan, parts of Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat, was a unified Hindu kingdom ruled by several houses of Rajput rulers. The land was well known for its trained warriors who lived with chivalric values and defended their motherland from invaders. The Rajputs put utmost importance on marriage alliances to strengthen their armies. The solidarity within many Rajput clans ensured that they stood together unflinchingly in the face of several invasions that tried to obliterate their cultural identity. The etymology consists of two words Raja meaning king, and Putra meaning son. They were the patrilineal clans that ruled central, western, and northern India and rose to prominence between the 6th to 12th centuries. We need to identify and acknowledge the socio-cultural locus of the Rajput culture to understand women’s role and agency in their society. The history of the Rajputs is an inseparable part of the history of the Rajput women, their frigid gender roles, and the social expectation of conduct placed on them. It is also important to understand the place of Rajput women in their societies in order to understand their predicament of Jauhar from the lens of pragmatism rather than the inflated lens of traditional pride. Humanizing the Rajput Women of Medieval RajputanaThe medieval Rajputana was not the ideal place to be a woman. To be honest, it was not an ideal time to be a woman in most parts of the world. Although the societal role of women in public life was pivotal amongst the Rajputs, the firm fists of patriarchy still restrained them from experiencing the necessary freedom of expression. Individuality is denied and discouraged to a royal Rajput woman. The patriarchal Rajput household has linear power dynamics and a gender-specific code of conduct. Rajputs were particular about their ethics of war, living, and behavior both within the domains of domestic and social life. The Rajput women lived in separated quarters known as Zenani Deorhi where all the women of the palace lived and were given the privilege as per their status. Male relatives above the age of seven years were not allowed inside the Zenani Deorhi. This social order has been directly inspired by the Mughal Harems. Historians observed that, before the arrival of the Muslim rulers, the gender barriers of separated living quarters were not present among the royals. The women lived with a certain level of freedom within the palace ground. The influence of the Mughal sultanate’s Hijab practice also inspired the system of Parda (veiling the face) among the royal Rajput women. None of these practices have any regard or respect for feminine expression and individuality. Women were reduced to their marital status. She was either liability to her father or a responsibility to her husband. She was the enviable richness of the throne when young and a symbol of purity when old. She is also an empty vessel and the womb to provide a male heir. She is the object of fascination and stories, a montage of inspiration and pride, a source of worship, and a figure of submission. She is anything but a woman. One hidden aspect of the inner lives of the Rajput women was the presence of a mammoth Havan kund (a place for ritualistic burning of offerings made to God) inside the Zenani Deorhi. The foreboding presence of these massive tanks holds a dark secret about all the wars that the Rajputs have lost. Screaming from within those endless pits are stories of numerous women and children of Rajputana who died violent deaths during foreign invasions. These tanks are known as Jauhar kund (or place to practice the tradition of Jauhar). The fort of Chittorgarh, which was once known as the most impenetrable architecture in the North-Western kingdoms of India, still in its debilitating presence, exhibits the well-preserved Jauhar kund in the women's quarters. It stands as a symbol of wonder and awe and reminds us of the Rajput women who bravely walked into the arms of death. The Forgotten History of JauharEtymologically, the term Jauhar has been derived from the words Jiva (life) and har (to destroy or take away). The documented history from the Mughal era explains Jauhar as the practice of mass self-immolation committed by women along with their children. When Rajputs sensed an imminent defeat, they would practice the ritual of Jauhar-Saka. In this traditional war ritual, the women and children committed Jauhar, which is suicide by mass immolation. And men carried out the ritual of Saka, which entails them to fight on the battlefield till they die. Traditionally, Saka is observed after the women engage in Jauhar. This practice was considered to be the last resort to save oneself from the dishonorable fate of slavery. Although the Jauhar tradition is closely associated with the Rajput rulers, the earliest known case of Jauhar was carried out by the Agalassoi tribe of northwest India (a part of the Indus Valley civilization) during the invasion of Alexander’s army. The ritual of Jauhar or self-immolation is as old as time and has its roots in Sanātana Dharma (Hinduism). This is a conclusive argument because the medium of death is fire. In Hinduism, fire is one of the most significant elements of nature. It is an element of chastity and purity. It is an element of worship and is significant in ritualistic practices to bridge a direct connection with God. Many western historians and scholars consider the tradition of Jauhar misogynistic. The fact that women and children were first led to their violent deaths and the men followed them later on the battlefield says a lot about the patriarchal structure of the society. Even if flawed in its disposition, the ritual is anything but proof of misogyny. The armies of Muslim invaders had a notorious reputation to take women of the fallen kingdoms as sex slaves. Women were war bounties to be raped and sometimes even killed. There were also rumors of heinous war crimes such as necrophilia and pedophilia. A life led in servitude to such monstrous masters was not an acceptable fate among the proud Rajput women. They would embrace the solace of death rather than surrender to their enemies. They were determined to not leave behind even their dead bodies because those could be subject to defilement. The Rajput women had as much pride in belonging to the Kshatriya (warrior) race as their husbands, fathers, and sons. Even if most of them were not as masterful in wielding weapons as their male counterparts, they had the upbringing and spirits of warriors. In those specific areas of character development, the Rajput women were complete and independent. They had a deep sense of self-respect and would not live under the subjugation and humiliation of foreign men. I can almost assure you that even if their husbands would not have coerced them to jump into the fire, the Rajput women under no circumstances would have wished to survive as sex slaves. Landlocked and surrounded by a massive enemy force, there was no escape for thousands of women who were untrained to fight an army. Even if one wants to see Jauhar as an act of desperation, one cannot deny the courage and the meticulous planning needed to succeed in such an extreme mission. Transforming victimhood into martyrdom is no mean feat, and that was the achievement of the Rajput Queens, who headed the Jauhar processions each time the kingdom fell. Medieval Rajputana was a kingdom of sand. As far as the eyes could see, an infinite ocean of dreadful sand and waves of desert dunes engulfed all forms of life. The magnificent fort of Chittorgarh stood like a wall between the dread of the dry land and the sprawling royal life with its numerous lakes, ponds, castles, towers, shrines, temples, and a massive city that inhabited thousands of subjects of the king who held the fort. It was a masterpiece standing the test of time, protected by many generations of Rajputs who were ready to bargain their heads to make the fortress the safest place in the kingdom. The sacrifices made to save the dignity of traditions established within the fort are innumerable, including the three famous incidents of Jauhar of Chittorgarh. The Veiled Ferocity of ChittorgarhThe city of Chittor is now slowly fading into the cradles of oblivion. But once upon a time, this golden city was known as the holy land of Shakti (Power), Bhakti (Devotion), Tyaag (Sacrifice), and Balidaan (Martyrdom). Many legendary heroes and heroines have graced the land with immortal tales of virtues. The tale of power was of Maharana Pratap, a folk hero who lead iconic guerrilla warfare against the expansionism of Akbar. The tale of devotion was of Meera Bai, the saintly devotee of Lord Krishna who, as legend has it, swallowed poison and didn’t die. The tale of sacrifice is that of Panna Dai who was the wet nurse of Udai Singh the crown prince of Mewar. To protect the prince from the unprecedented attacks of his uncle, Panna dai sacrificed her son who was of the same age as the prince. The final tale of martyrdom is of Rani (Queen) Padmini, made popular by a Sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi in his poetic work ‘Padmavat’ written in both Awadhi and Persian languages. This poetry is written in a play-like format where various parts progress towards a climactic end scene where Rani Padmini entered into an ablaze Jauhar kund with thousands of women of Chittor. It is said that 27 attacks were made on Chittorgarh fort over a period of time by various invaders, but the Rajputs lost only thrice. Historians believe that the siege of 1303 by Alauddin Khalji’s force eventually led to the fall of Chittorgarh and the first Jauhar of Chittor. Alauddin Khalji was well known for his savage war strategies. When the Mongolian army threatened an invasion of India, Jalal-ud-din, the then Sultan of Delhi and founder of the Khilji dynasty, appointed his ruthless nephew Alauddin as his general. Alauddin with his few men successfully fended off the massive army of the barbaric Mongols. Soon after, he murdered his uncle and ascended the throne of the Sultan of Hindustan (India). The remorseless Alauddin, unleashed from his uncle's authority, started his reign of terror which lasted 20 years. A period that marked the raiding and conquering of several flourished Indian kingdoms like Ranthambhor, Mandu, Devagiri, and Chittorgarh. Alauddin’s army was infamous for its post-war brutality toward the surviving civilians. Jayasi’s poem, which is considered a fictitious tale, narrates the backstory of Alauddin’s motivations in thrilling details. Jayasi’s Version of the TaleIn the 13th century medieval kingdom of Sinhala (current day Sri Lanka), there lived a princess of extraordinary beauty and intelligence. She eventually married the king of Chittor Rawal Ratan Singh, after he succeeded in an adventurous quest to win her love. After she came to Chittor, the rumors of her elusive beauty spread throughout the kingdom and beyond. When the news reached the insatiable Alauddin, he decided he had to attain her at any cost. He led the siege of Chittorgarh fort unannounced but could not penetrate the fort walls. Alauddin was not someone who would give up so easily, so his army surrounded the fort and blocked all routes of food supply inside the fort city. But the burning heat of the desert land crushed the spirit of his men. He feigned a move of friendship towards the Rawal and then deceitfully captured him and took him to Delhi. He then blackmailed Rani Padmini to come to Delhi to free her husband. The astute Queen wrote back that she would only come if the Sultan send 700 palanquins for her female servants who are going to accompany her to Delhi. Alauddin agreed, and Padmini stealthily sent 700 armed men dressed in female attire to bring back her king. Enraged by this betrayal and the fact that Ratan Singh escaped from right under his nose, Alauddin took all his men to besiege Chittorgarh. When defeat seemed inevitable, Rani Padmini beckoned to all the women of Chittor and started preparing for Jauhar. All the women adorned themselves in the majestic bridal red, the color of blood and motherhood, of bravery and sacrifice, a sacred symbol of womanhood to Hindu women. They wore all their best jewelry of gold and precious stones and started a procession spreading vermillion on their path, bellowing the name of their beloved goddess Durga, the fierce protectress who annihilates all tormenters. To free her people from the tyranny of invaders, Rani Padmini set every log of Chittorgarh to flame and took all the children with her too. The men wearing the saffron color of martyrdom fought on the battlefield till they died. By the time Alauddin entered the fort, the whole of Chittorgarh was nothing but an immense crematorium. All he could touch and hold were white ashes of disappointment and embarrassing defeat. And thus, Rani Padmini transformed the moments of agony into martyrdom. Even if Khilji won on the battlefield, his ulterior motive to subjugate the beauty and brilliance of Padmini failed. He lost the ideological war to the Rajput women who fought without any brute force or weapons. Rani Padmini might be a fictional character, and so is her story, but the other two incidents of Jauhar that took place inside Chittor are not fictional. The second one took place on 8 March 1535 led by Rani Karnavati alongside 13,000 Rajput women, and the third in the spring of 1568 CE by the collective Rajput women of the fort. Both times Chittorgarah fell at the hands of Bahadur Shah and Akbar respectively. The horror of the later years was well documented from the first-hand experience of the surviving armies and the emperor Akbar himself. The story of Padmini’s Jauhar sounds like an overly romanticized take on what happened inside the walls of the fort that day. However, one cannot deny that the existence of a custom-like Jauhar speaks of the unfathomable evil manifested through humans leading to a crisis where mass suicide seemed to be the only option left. Moreover, Alauddin khilji was a real tyrant with a diabolic appetite to conquer. Therefore, the incident like that of Jayasi's story is plausible and not unnatural for its period. Even in her fictional existence, the veiled strength of Rani Padmini is more clearly ingrained in the collective mind than the toxic masculinity of Khilji. Padmini stood by what she believed in, and she will forever remain an archetype of feminine strength and integrity. Padmini’s story is a feminist take on the pitied helplessness of medieval women. It is, if anything, a tool to turn the patriarchal narrative on its head and give the Rajput women their own choice and agency in death, which they severely lacked in life. |

Older messages

An Ode to the Heat

Sunday, May 22, 2022

Summertime Nostalgia of Pickles, Folklores, and Profiling of Ghosts

Her Hungry Skin with Star and Moon

Sunday, April 24, 2022

Stories of the Forgotten Armenian Girls Enslaved by the Ottoman Empire

Peeping through the shadows

Saturday, April 2, 2022

Meditating on the legacy of Berkana

Ghosts of war

Monday, March 21, 2022

Stories from a Forgotten Colonial Holocaust

War on Apathy

Saturday, March 12, 2022

A game of Pride and Prejudice

You Might Also Like

2025 Personal Development Goals 🎓

Friday, December 27, 2024

New year, new goals? ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Weekender, December 27, 2024

Friday, December 27, 2024

The last one of the year

Closes Tonight • New Year's Day Newsletter Promo for Authors ●

Friday, December 27, 2024

Book Your Spot Now in Our New Year's Day Holiday Books Email Newsletter ! Book Your Spot in Our New Year's Day Email Newsletter Enable Images

🧙♂️ "Maybe next year will be different..."

Friday, December 27, 2024

How many times have you told yourself that? ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

🎤 The SWIPES Email (Friday, December 27th, 2024)

Friday, December 27, 2024

The SWIPES Email Friday, December 27th, 2024 An educational (and fun) email by Copywriting Course. Enjoy! And MERRY CHRISTMAS OR WHATEVER HOLIDAY YOU CELEBRATE! Swipe: I loooveeee when images

Copywriting wins of 2024

Friday, December 27, 2024

The skill of copywriting is making content that attracts people... ...then eventually convert some people into an action (email signup, get a lead, or make a sale): The goal of copywriting is

23+ Great Ideas for Your 2025 Playbook

Friday, December 27, 2024

Plan for the best year with these tips. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Closes Tomorrow • New Year's Day Newsletter Promo for Authors ●

Friday, December 27, 2024

Book Your Spot Now in Our New Year's Day Holiday Books Email Newsletter ! Book Your Spot in Our New Year's Day Email Newsletter Enable Images

🤯 You’re Not Going to Believe This…

Thursday, December 26, 2024

No One Wants This $165B Gift Contrarians, How does this make you feel? Like the Grinch stole our businesses' souls? Like Main Street packed up and left for the North Pole? This shot might look

3-2-1: On making a comeback, revising your habits, and how to work smart

Thursday, December 26, 2024

“The most wisdom per word of any newsletter on the web.” 3-2-1: On making a comeback, revising your habits, and how to work smart read on JAMESCLEAR.COM | DECEMBER 26, 2024 Happy 3-2-1 Thursday!