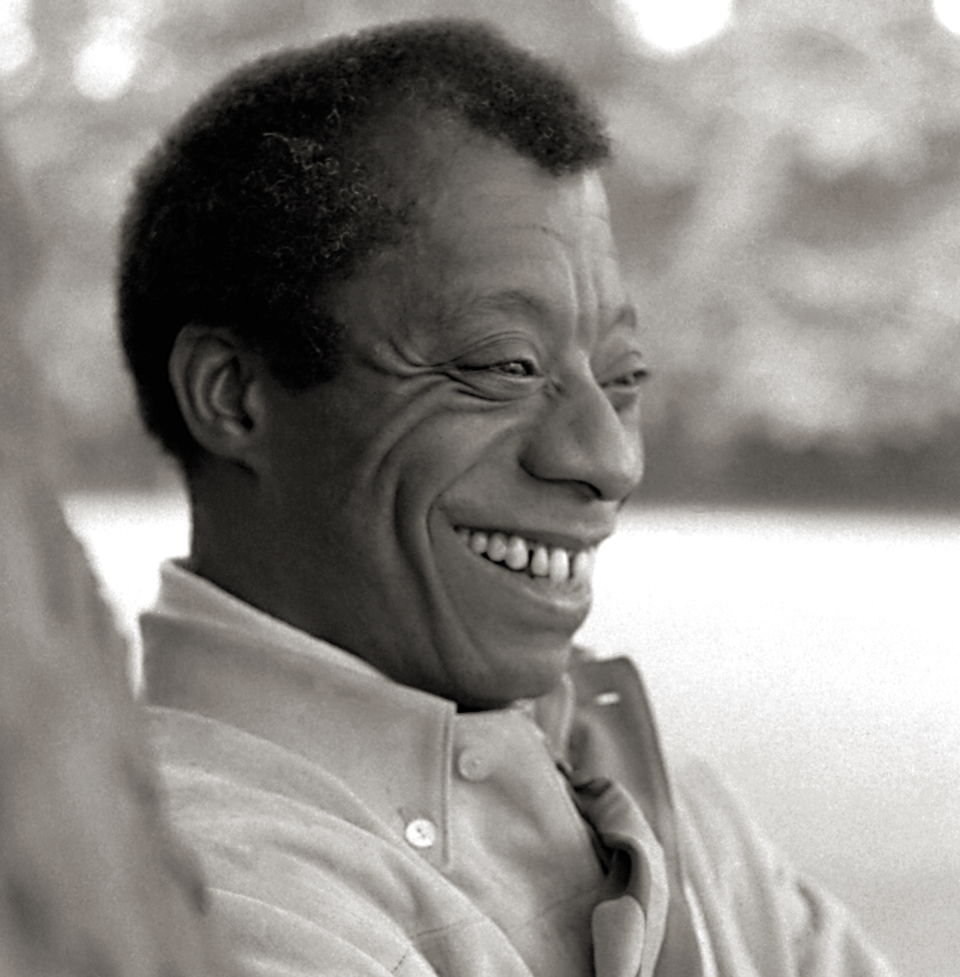

Such a Thing as GraceBy John Metta John Metta’s letter to his beloved niece, Jayla, emulates Baldwin’s, but it focuses on surviving and thriving in the face of the rigors common to living as a Black person in a predominantly white world.  Photo by Mike Vonn at Unsplash.com Dear Jayla, For five years I have considered writing this letter, and for five years I have let cowardice stay my hand. I keep hearing voices in my memory, voices I loved as a child and love still. They tell me with hugs and reassurances that we are all the same. That there is no need to talk of these things. That, indeed, they only exist because we, by continuing to talk of them, breathe into them life. A Black childhood in a white family is an ocean of words you cling to for breath even as they pull you into their depths. I have avoided writing to you for five years because for ten times as many years I heeded those words, trying to believe them because they came from a place of love. Only after having children of my own did I even begin to see love’s cowardice. Your mother, I am given to understand, has seen this too, now, and faced it. That is a commendable feat. It is one thing for a white mother to adopt a Black child and remain unchanged and unchanging in a society which condemns the child. It is another experience wholly to, in the words of your mother, realize how many friends and family do not believe your child has a right to exist. To face the demon at his very gates. I have always loved your mother as the bird loves the summer sky. I hope facing that demon has not drained her summer’s golden warmth. I have so long considered, but not taken action to write to you because I have for so long struggled to understand my own place, indeed to believe my own story. What offer could I bring to you that would contribute to the understanding of your life? What would I write? Indeed, who was I to assume I was even welcome, three thousand miles away? What right do I have insinuating myself into your presence? But that question proved the force necessary to move my pen to paper, because we are, in some great and lonesome sense, the same in this. You are, as I was, a Black child in a white family, and you will therefore ever find yourself in what sociologists have begun to call White Space. (Do appreciate the horror of this term and its definition, that being, the spaces that are defined specifically by the lack of people who look like you.) In your life in these spaces, you will ever be an intrigue, a confusion, a misplacement. You will be an errant brush stroke on the canvas of an otherwise perfect painting, notable not for what you are, but for where you do not belong. It is important that you realize now that this is not the truth. Read the full article at OHF Weekly. Hope Amidst HopelessnessBy William Spivey “James Baldwin was under no illusion about America. He saw the good and the evil. The answer doesn’t lie in fixing Black people. Baldwin knew this when he told his nephew, ‘We cannot be free until they are free.’” –William Spivey In perhaps the only way I’ll claim similarity to James Baldwin, I started this story multiple times before deciding on a direction. I had the disadvantage of having months before it was due, allowing procrastination to disrupt my normal process. I read his letter to his nephew many times, hoping a theme would inspire me. Instead of inspiration, I just felt sadness reading Baldwin’s description of America and Harlem in particular to his nephew, also named James. The uncle and famous author was not kind in his description of America. He said, “Neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it.” Yet at the end of the letter, the uncle offered encouragement, pushing the nephew to persevere, reminding him of who he was and where he had come from. The suggestions as to how to accomplish that were few. James Baldwin, the uncle, himself left the country, spending most of his later years in France—though never leaving the movement in America. I wondered how the nephew James received the letter. Did he find motivation from his uncle’s words, or did he simply agree with his uncle’s assessment and simply try to survive? Did the namesake know from whence he came, and govern himself accordingly? During the period in which I knew this article was to be written but nothing had been produced, I took a journey I’d been long planning but had been disrupted by COVID-19. My trip included some locations I’d written about previously but never personally seen: Lumpkin’s Slave Jail in Richmond, Virginia, Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina, the Slave Market in St. Augustine, Florida, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Virginia. As an aside, I visited the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, in Washington, D.C. What I’d heard about the monument had been negative, what I saw was inspiring. I’m reminded never to let someone else tell your history. Baldwin and King marched alongside each other. It was King’s assassination that led Baldwin to seek refuge abroad. I believe he was tired of an America whose dream was not only deferred but denied to Black people, as Langston Hughes once wrote. When I stood at the bottom of the thirty-foot statue of King, I found the inspiration for this story that had been sorely lacking. I found the link between the description of America that seemingly never did the right thing and the hope Baldwin tried to instill in his nephew as if America would one day do better. Baldwin wrote: “Great men have done great things here and will again and we can make America what America must become.” Neither Baldwin nor King was under any illusion about America. They saw the good and the evil. King said, “The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Read the full article at OHF Weekly. The Fall into FreedomBy Rebecca Hyman OHF Weekly writer, therapist, and corporate trainer Rebecca Hyman expounds upon three concepts from James Baldwin’s “A Letter to My Nephew,”—innocence, experience, and love—as applied to her life and how we all might benefit from the same.  Images by Our Human Family. Baldwin writes in his “Letter to My Nephew” about a peculiar characteristic of white people: they are blind. They live in a monochromatic world, attuned only to the experience and needs of other white people. In the way that snow blunts, distorts, and renders the physical landscape softer to the eyes, even as it makes the environment inhospitable to survival, so whiteness covers over its own violence, insisting the world it creates is beautiful, and benign. Whiteness believes itself pure and light; its people good and worthy; its inventions useful; its philosophy moral. White people rest in the soft, downy pillow of their own superiority, believing their success the product of their own effort. It is the quality of not seeing whiteness, and not knowing the pain and violence being committed in its name, that Baldwin labels “innocence.” Coddled and spoiled, white people are immature and quick to take offense if they are criticized. Attempts to remove the clouds from their eyes are unlikely to succeed. And yet, there is something in the experience of whiteness that is inherently dissatisfying. By staying in a self-referential space, white people lack the ability to connect with others, to grow up, to achieve psychological complexity. Their relationship to the external world, a mirror of their internal poverty, is flat. Baldwin counsels his nephew to “accept with love” this white innocence. To truly love a white person is to ask them to see themselves “as they are.” For it is in the moment of gaining sight—of seeing one’s professed innocence as in actuality participation in a crime—that the white person has a chance to become fully human, engaging in the painful, hesitant, and uncertain work of undermining and overcoming white supremacy. InnocenceImagine waking one day, Baldwin says of this white person, “the sun shining and all the stars aflame.” The encounter with the truth of white violence is Biblical in its force: “the black man has functioned in the white man’s world as a fixed star, an immovable pillar: as he moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations.” When I read this passage, it sounds like white innocence is shattered at once—the old self is forever changed, in the way that Paul, who persecuted the Jews with zeal, is converted on the road to Damascus when he encounters the risen Christ. But when I look at my own history, I see a different awakening. A slow dawn, the light etching the horizon. The clouds first red, then pink, then white. Finally, a light so brazen I cannot face it without pain and an instinctive cowering before its force. I am three. I climb onto my best friend’s lap and pull his dark face to mine and kiss him, because I love him and I want to know what kissing feels like. I don’t remember how he came to be my best friend, and I don’t remember why or when he disappeared from my life. I just know that when I think of my childhood playmates—all the other kids were white. Where did he go? Why didn’t I notice? Read the full article at OHF Weekly.

|