Net Interest - Deglobalised Banking

In between writing Net Interest, I write a column for Bloomberg Opinion. The content is similar – reflections on the finance industry, buttressed by 25 years of experience investing in the sector – but the pieces are shorter, which means good stuff often hits the cutting room floor. This was one of those weeks. I wrote about the demise of global banking through the lens of HSBC and Citigroup but, zoomed out, the piece was also about the demise of globalisation through the lens of global banking. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted a reassessment of the benefits of globalisation and, for those entities that shaped their business models around it, that creates a challenge. For years, these banks struggled to convince investors of the value of their global networks; now their task is much harder. To understand the depth of the challenge, we need to go back in time to the days of Frank Vanderlip, the architect of Citi’s global strategy… Today’s edition of Net Interest is brought to you by Third Bridge. Third Bridge Forum is the biggest archive of expert interviews in the world. Just last year over 16,000 investment professionals from 1,000 firms across private equity, public equity and credit downloaded over 500,000 interviews. The coverage is extensive – covering both public and private companies, in any sector, across all major geographies. I’ve seen it for myself – the insights Forum delivers are in-depth and unique. If you want to request a free trial visit thirdbridge.com/net. Deglobalised BankingToday, Citigroup and HSBC are two of the most globally diversified banks in the world. “We open our bank’s doors in 97 countries every day,” Citi’s CEO, Jane Fraser, said recently. HSBC is a little further behind – according to its annual tally, it currently has operations in 64 countries and territories – but, as “the world’s local bank”, it is no less recognisable around the world. Yet neither of them set out to be global banks. Citi was founded as the City Bank of New York just before the outbreak of the War of 1812 and spent its first few years helping to fund the United States in its war effort against the United Kingdom – hardly an ideal foundation for fostering business overseas. HSBC was founded over 50 years later by a group of trade merchants in Hong Kong, frustrated that foreign banking groups active in the region were unable to deal satisfactorily with local trade matters. For many years, the two banks focused exclusively on domestic affairs. It took Citi just over a hundred years to venture overseas. By the dawn of the 20th century, the bank had grown to become the largest in America and from this position, it began to spy opportunities abroad. In 1903, its vice president (and former assistant Treasury secretary) Frank Vanderlip sketched out his vision at a speech at the New England Club in Boston:

It may have been no coincidence that the architect of Citi’s plan to expand internationally was a Treasury man, whose motivation was as much political as commercial. Faced with regulatory restrictions on branch openings at home, coupled with an appetite to represent “our exporting interests in the world’s markets”, Vanderlip began laying down branches abroad. In 1914, Citi opened the first foreign branch of any nationally chartered US bank, in Buenos Aires, Argentina and went on to open branches in Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, Cuba, Russia and elsewhere. By 1920, Citi had 81 branches in outposts around the world. “The bank was growing, growing, growing,” recalled Vanderlip, who noted that his foreign branches “developed faster than we could find trained men to run them.” The first wave of international expansion didn’t go smoothly. The Bolsheviks nationalised Citi’s St. Petersburg branch within a year of its opening. And in Cuba, the bank built up a huge exposure to the sugar industry just in time to see the price of sugar collapse as European production came back on stream after the First World War. But Citi continued to expand – by 1930 it had established 97 branches abroad. It took further political impetus to secure Citi’s international position following the Second World War. Under the Marshall Plan, the bank arranged commercial letters of credit for shipments to countries receiving US government aid. More broadly, the bank was able to take advantage of America’s new position as world superpower to expand its international commercial banking operations. The man that drove this forward was Walter Wriston. In 1967, Wriston was promoted from head of the bank’s overseas division to group president. He’d made his own vision very clear at a divisional dinner a few years earlier:

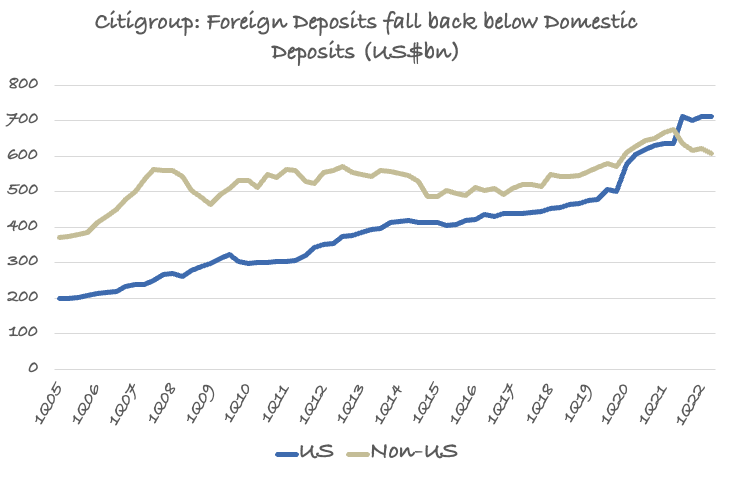

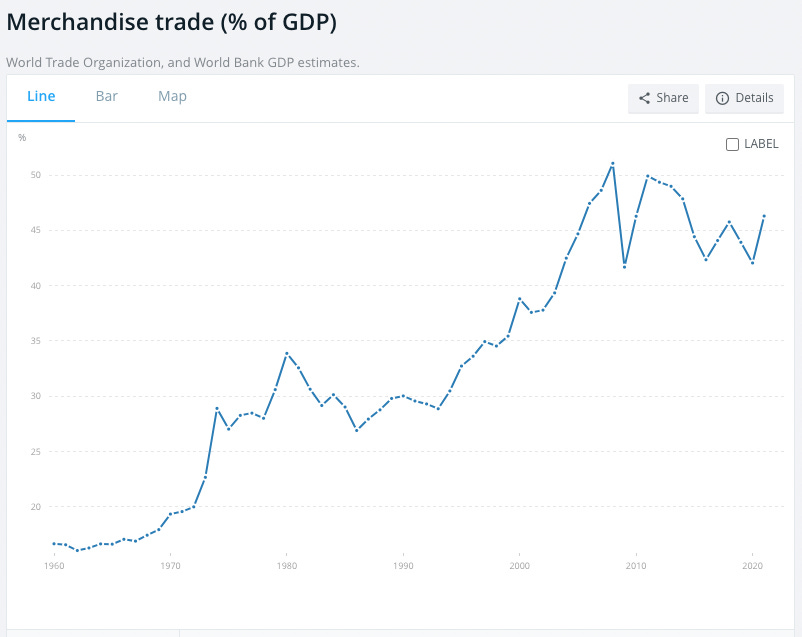

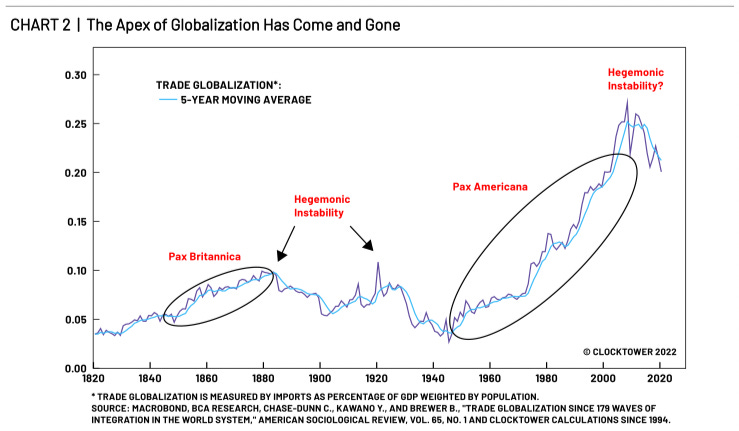

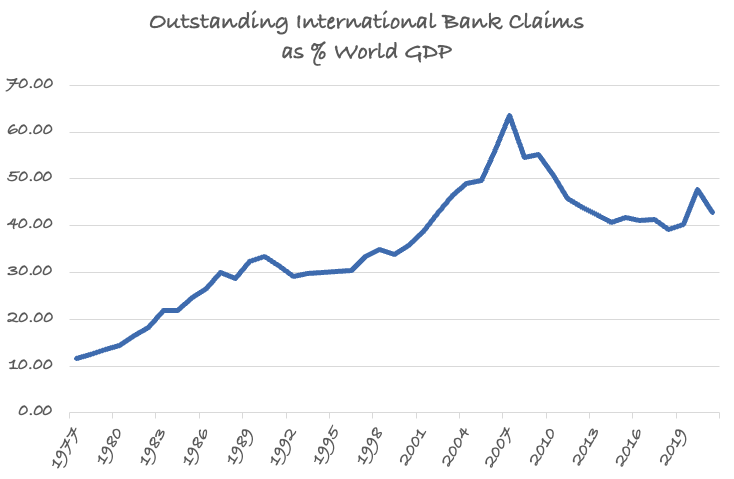

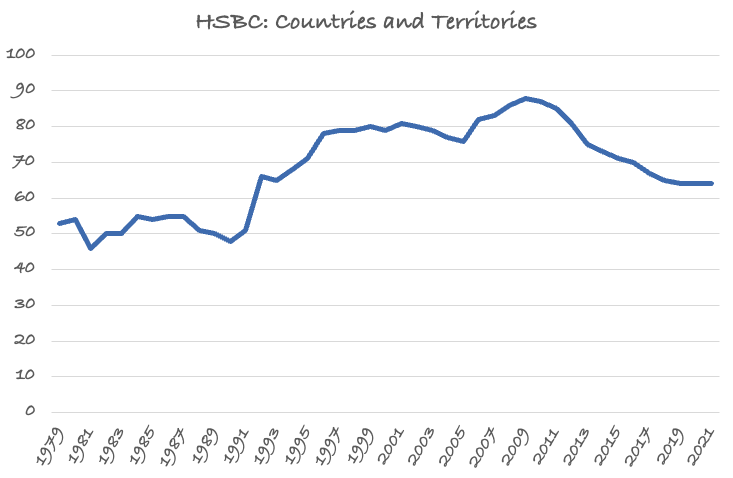

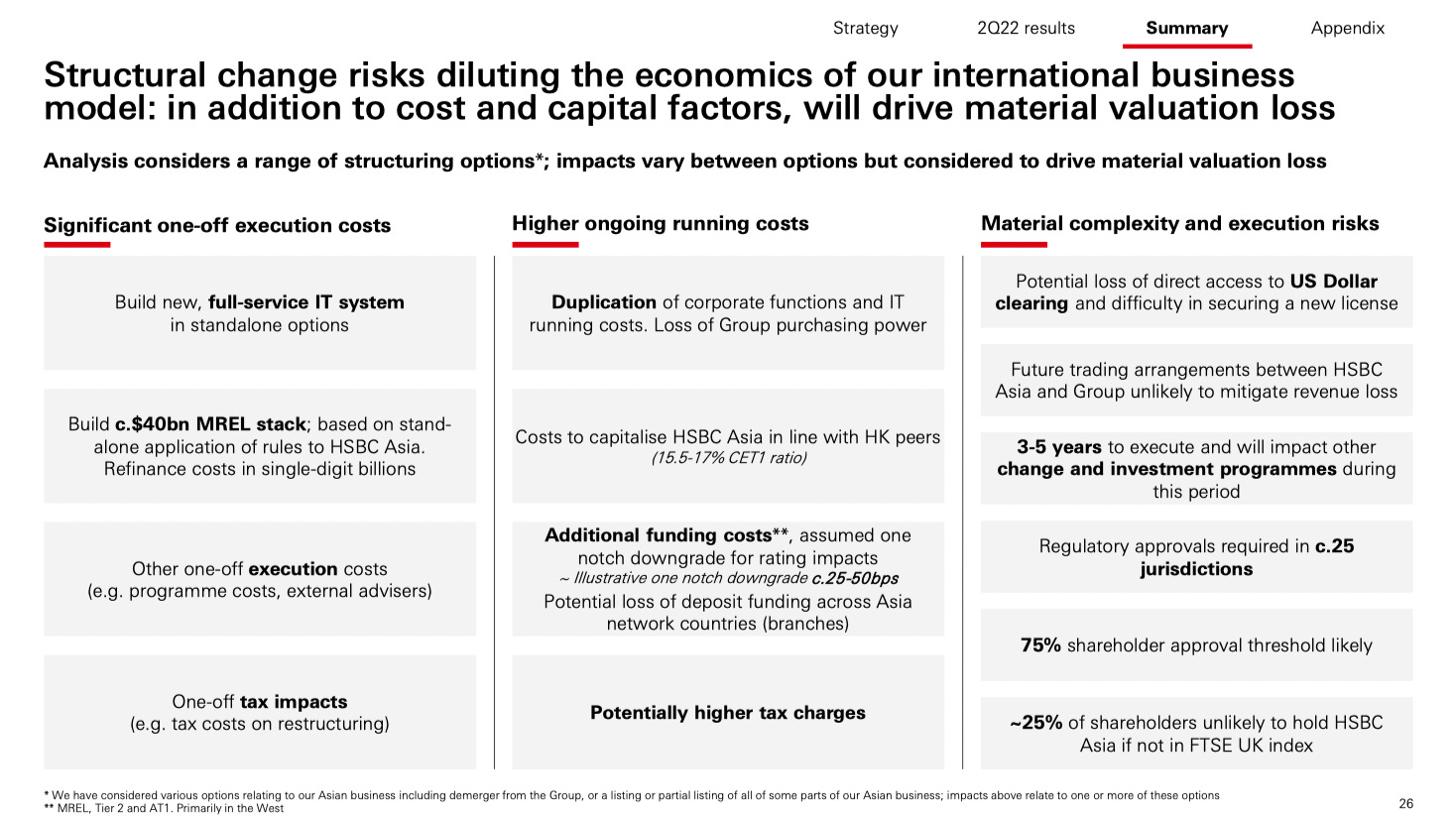

As president, it was on Wriston’s watch in 1973 that foreign deposits first exceeded domestic deposits, a situation that persisted for many years … until last year. HSBC: “The World’s Local Bank”HSBC’s path to global diversification was somewhat different, although it shares a couple of features. Like Citi, HSBC grew to dominate its local market. It made efforts to diversify internationally via the acquisition of two British overseas banks, Mercantile Bank and British Bank of the Middle East, in 1959, but doubled down on Hong Kong a few years later, when it was called on to bail out struggling Hang Seng Bank in 1965. For many years, its fortunes were tied to those of Hong Kong. Until the formation of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority in 1993, HSBC served as the region’s de-facto central bank. Part of HSBC’s motivation to expand abroad was to tap into new opportunities for growth. In 1977, Michael Sandberg assumed the role of chairman with a strategy to create a “three-legged stool” underneath the bank, with legs in Asia, North America and Europe. “If you stand still these days you are in fact moving backwards,” he declared. “I think you just reach a stage where you’re in a two-bedroom apartment, you’ve got four kids and you’ve got to move to a bigger one.” But as with Citi, there was also a political undertone to the ambition to diversify internationally – in this case, the handover of Hong Kong back to China in 1997. There was a lot of uncertainty at the time over what the future would hold. Contemplating the transition, an internal report in 1990 cautioned that “there will be times when depositors, borrowers and other customers of the Group’s range of financial services will be reluctant to deal with it because of political uncertainty in Hong Kong.” In addition, most of the bank’s senior executives were British and they wanted to retain control (in 1981, all but 10 of the 500 senior executives of the bank were British). “I think if we did absolutely nothing, because we’ve headquarters in Hong Kong, because Hong Kong…will be Chinese territory, it must be absolutely as night follows day that we would become a Chinese bank,” Sandberg told the bank’s historian. “It would be a complete anachronism to have all our senior officers British, I doubt it would be allowed.” The solution was to move the centre of gravity of the group from Hong Kong to the UK. The bank had been looking for acquisitions in the UK for many years. In 1981, as part of its “three-legged stool” strategy, it commissioned a paper to study the broader European market. The paper went through the opportunities available across the various markets, ruling out France and Italy because of “difficulties of entry, regulation and the local dominance of ‘profitless’ state banks”, and Germany because of the “low level of profitability” on the part of “forty possible acquisitions examined”. [Plus ça change.] That left the UK. The bank put a bid in for Royal Bank of Scotland but it was blocked by the authorities. Finally, years later in 1992, an opportunity to acquire a different UK bank, Midland Bank, arose. HSBC was anyway in the process of creating a holding company incorporated in London, but the deal provided cover for a full move. With the addition of Midland Bank’s 46,000 employees, HSBC’s worldwide headcount almost doubled to 99,000. Beijing was initially supportive although later accused the bank of wanting “to gradually fade out of Hong Kong.” One difference with Citi was HSBC’s appetite for US dollar funding, which Citi by contrast had in abundance. Before embarking on its acquisition in Europe, HSBC first forayed into the US, where it acquired Marine Midland, of Buffalo, New York, in 1980. It wasn’t for the profit potential: “The profit motive was not the major motive,” said the bank’s general manager for overseas operations. “It was really a question of becoming a major international bank with greater stability – a stabilisation move.” As a non-US bank in a dollar-based world, HSBC has retained its demand for stable dollar funding. On his earnings call in February 2020, CEO Noel Quinn reminded investors that, “a retail deposit base in the US provides an important source of stable liquidity for our wholesale banking and global transaction banking activities.” Yet dollar funding is now more widely accessible than it once was. During the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve set up swap lines with other central banks around the world to defuse a US dollar shortage among global banks. The Fed now has standing swap lines with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank. At the outset of the pandemic, it quickly set up temporary facilities with nine more central banks. Direct access to onshore US dollar funding is therefore less of an advantage than it once was. Ironically, because the architecture around banking has globalised, the need for any one bank to establish a proprietary global network has lessened. But that’s just one of the changes that have undermined the value of a global network. There’s also the outlook for globalisation itself. The End of Globalisation?For many years, both Citi and HSBC benefited from greater economic integration between countries around the world. In its 2009 annual report, Citigroup stressed its determination “to capitalize fully on Citi’s most immediately distinctive trait that our competitors cannot match: the strength of our global positioning and network.” It listed several major trends linked to globalisation that it sought to exploit – a rising wave of middle-class consumers in emerging markets, healthy export markets, more multinational companies, individuals becoming “citizens of the world”. But major trends aren’t all one-way. President Bill Clinton was short-sighted when he characterised globalisation as “not something that we can hold off or turn off: it is the economic equivalent of a force of nature – like wind or water”. As Howard Marks, Co-Chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, argued in a memo recently, in geopolitics, as in economics, there are few options that offer only positives and no negatives – there are only trade-offs. For years, globalisation thrived on the back of improvements in transportation and communications and an environment of relative peace. However, when the tide goes out, negatives often become apparent, which they certainly have since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The war has exposed vulnerabilities around energy dependence on top of any income inequality that globalisation fostered. In Marks’ words: “The recognition of these negative aspects of globalization has now caused the pendulum to swing back toward local sourcing.” Larry Fink, Chairman and CEO of BlackRock, agrees: “The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put an end to the globalization we have experienced over the last three decades,” he wrote in his annual shareholder letter this year. In fact, globalisation likely peaked years before the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War. One measure of globalisation is global goods trade – the sum of merchandise imports and exports. According to World Bank data, it peaked in 2009 (at 51% of global GDP) and has been on a downward trend since. That reflects countries becoming more inward, notably China, which has reduced its reliance on trade as it has become richer and demand has shifted away from goods and towards services which are typically provided locally. It also reflects the emergence of more regional trading blocs as well as less political support for global economic integration – unlike in Vanderlip’s time at Citi. Marko Papic of Clocktower Group analyses longer-term data. He takes a more geopolitical perspective, pointing out how the environment has become more multipolar since the US became more insular. “Without a single great power, a hegemon, to enforce rules and norms of behavior, how does globalization persist?” he asks. The broader economic data is consistent with banking data. International claims outstanding on banks’ balance sheets grew from 2% of world GDP in 1963 to over 60% in 2007, before retreating to nearly 40% in early 2021, according to data compiled by the Bank for International Settlements. Some of that reflects deglobalisation, but some reflects banks themselves becoming less relevant as intermediaries, constrained by post-crisis reforms in regulation. It’s true that the concept of globalisation has many attributes. It covers cross-border movement of goods, capital, people, technologies, data and ideas. In the past, flows on each of these axes were very highly correlated, but some divergence may now be afoot. While global goods trade may have declined, and people flows may also be in decline with less migration, technology and ideas continue to traverse borders freely. World exports of computer and communications services have been trending up since the early 1990s. Goldman Sachs economists coined the term ‘newbalization’ to reflect that cross-border flows may slow in tangible areas like goods trade, while at the same time accelerating in intangible areas. The problem for global banks is that they were set up to facilitate tangible trade financing. Some have already responded. HSBC has reduced its global footprint from 88 countries at the peak of globalisation in 2009 to 64 currently. Citi has exited a number of consumer markets but remains committed to its global model in institutional banking. But global banking is a hard thing to unwind. Turns out, it’s a lot easier to enter a new country than it is to exit. Back in 2000, HSBC made a decision to bolster its presence in France. It identified a target, CCF, and bid more for it than anyone else. Getting out was less easy: CCF was on the market for over a year and eventually HSBC had to accept just 1 euro from Cerberus to take it off its hands at a loss of $2.3 billion. Several banks are currently discovering that it’s more difficult to exit Russia than they anticipated. The appreciating ruble means that assets are growing faster than they can be dumped. Raiffeisen International Bank, which has the largest exposure to Russia relative to its size, cut lending by 22% in the second quarter, but saw its assets grow by €3.1 billion. Meanwhile, not only are buyers scarce, but sanctions complicate the sales process. HSBC draws attention to these obstacles in its defence of its current strategy. Its largest shareholder, Ping An, is agitating for it to spin-off its Asian business – essentially to unwind its “three-legged stool” strategy of old. At its recent results presentation, the bank laid out 14 reasons why this would be difficult to execute. According to management, it would take 3-5 years to do and come at considerable cost. The flipside is that a global network is hard to replicate. But a moat is only useful if the castle it protects is worth penetrating. As deglobalisation gathers pace, global banks are left defending an anachronistic business model that’s difficult to shed. For my history of Citi, I relied on Borrowed Time: Two Centuries of Booms, Busts and Bailouts at Citi, by James Freeman and Vern McKinley. For HSBC, I relied on The Lion Wakes: A Modern History of HSBC, by David Kynaston and Richard Roberts. You’re on the free list for Net Interest. For the full experience, become a paying subscriber. |

Older messages

Family Fortunes

Friday, August 12, 2022

The Origins and Growth of the Family Office

The Most Important Sector in the Universe

Friday, July 29, 2022

Plus: Brazil, Visa/Mastercard, Greensill

Battle of the Challengers

Friday, July 22, 2022

Plus: Options Trading, French Mortgage Lending, Dee Hock

The Great Unwind

Friday, July 15, 2022

Plus: Banks in Disguise (Naked Wines), JPMorgan's Reflexivity, Chinese Bank Protests

The Hedge Fund, the Bank and the Broker: How It All Fits Together

Friday, July 8, 2022

Plus: Countercyclical Buffers, Central Bank Stocks, Augmentum Fintech

You Might Also Like

Longreads + Open Thread

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Personal Essays, Lies, Popes, GPT-4.5, Banks, Buy-and-Hold, Advanced Portfolio Management, Trade, Karp Longreads + Open Thread By Byrne Hobart • 8 Mar 2025 View in browser View in browser Longreads

💸 A $24 billion grocery haul

Friday, March 7, 2025

Walgreens landed in a shopping basket, crypto investors felt pranked by the president, and a burger made of skin | Finimize Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 8th in 3:11 minutes.

The financial toll of a divorce can be devastating

Friday, March 7, 2025

Here are some options to get back on track ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Too Big To Fail?

Friday, March 7, 2025

Revisiting Millennium and Multi-Manager Hedge Funds ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The tell-tale signs the crash of a lifetime is near

Friday, March 7, 2025

Message from Harry Dent ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

👀 DeepSeek 2.0

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Alibaba's AI competitor, Europe's rate cut, and loads of instant noodles | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 7th in 3:07 minutes. Investors rewarded

Crypto Politics: Strategy or Play? - Issue #515

Thursday, March 6, 2025

FTW Crypto: Trump's crypto plan fuels market surges—is it real policy or just strategy? Decentralization may be the only way forward. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What can 40 years of data on vacancy advertising costs tell us about labour market equilibrium?

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Michal Stelmach, James Kensett and Philip Schnattinger Economists frequently use the vacancies to unemployment (V/U) ratio to measure labour market tightness. Analysis of the labour market during the

🇺🇸 Make America rich again

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

The US president stood by tariffs, China revealed ambitious plans, and the startup fighting fast fashion's ugly side | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March

Are you prepared for Social Security’s uncertain future?

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

Investing in gold with AHG could help stabilize your retirement ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏