[Original post: Unpredictable Reward, Predictable Happiness]

1: Okay, I mostly wanted to highlight this one by Grognoscente:

I think really digging into the neural nitty gritty may prove illuminative here. Dopamine release in nucleus accumbens (which is what drives reward learning and thus the updating of our predictions) is influenced by at least three independent factors:

1. A "state prediction error" or general surprise signal from PFC (either directly or via pedunculopontine nucleus and related structures). This provokes phasic bursting of dopamine neurons in the Ventral Tegmental Area.

2. The amount and pattern of GABAergic inhibition of VTA dopamine neurons from NAc, ventral pallidum, and local GABA interneurons. At rest, only a small % of VTA DA neurons will be firing at a given time, and the aforementioned surprise signal alone can't do much to increase this. What CAN change this is the hedonic value of the surprising stimulus. An unexpected reward causes not just a surprise signal, but a release of endorphins from "hedonic hotspots" in NAc and VP, and these endorphins inhibit the inhibitory GABA neurons, thereby releasing the "brake" on VTA DA neurons and allowing more of them to phasically fire.

3. It also seems acetylcholine may independently influence dopamine release in NAc independently of what's going on in VTA. This is less important for our purposes here, but it may help explain why cigarettes are addicting despite smoking not being particularly pleasurable.

Simplifying from 1 and 2 above, the unexpectedness of a stimulus affects the phasic firing rate of VTA DA neurons, and the hedonic value of the stimulus determines how many and which VTA DA neurons are allowed to phasically fire.

Now, what does the released dopamine do? In PFC (via the mesocortical pathway), it draws attentional resources to the surprising stimulus and its plausible causes, gating out the processing of other, less relevant stimuli. Simultaneously, in NAc, it strengthens connections between PFC inputs and the endorphin-releasing cells, thereby wiring together the hedonic features of the reward and the sensory features of any cues predictive of it. This imbues the cue with the ability to release the GABAergic brake on VTA DA neurons all by itself. Phenomenologically, it results in us "liking" the cue as much (or nearly as much) as we like the reward (this is what allows, e.g., animal trainers to reinforce behavior with only the sound of a clicker that has previously been paired with food).

But once the brain learns that a reward is reliably predicted by a cue, the reward ceases to elicit a surprise signal. This means it no longer increases VTA DA neuron firing rate. It may still cause endorphin release and thus keep the GABAergic brake off, but if there's no surprise signal driving phasic firing, dopamine release will be minimal.

That is to say: We still enjoy expected rewards; we just don't much *care* about our enjoyment of them. I don't think dopamine so much contributes a unique kind of happiness as it makes our happiness attention-grabbing, memorable, instructive, and motivating. *That* is what we lose when passionate love turns into companionate love.

The flipside of this is that we become very sensitive to unexpected *omissions* of reward. We take expected pleasures for granted as long as they keep coming, but woe betide anyone who suddenly threatens to take them away. This may add a certain kind of fragility to reliably pleasant relationships in the companionate love stage.

Abusive or otherwise volatile relationships keep partners engaged because they keep the good times unpredictable, thereby preserving their dopaminergic effects. Happiness on balance may be lower than in a more stable relationship, but partners over-learn from such happiness as there is, precisely because it is always surprising and thus significant.

But the physiological separability of the surprise signal and the pleasure signal suggests one may be able to keep a high baseline level of relationship bliss motivationally salient simply by being good to each other in surprising ways. So randomize (to an extent reasonable) gifts, dates, sexy times, vacations, and other fun things, along with their timing, and you should have at least some buffer against the decline of passionate love. Alas, this may be hard to do if your life is largely routinized by work, kids, or other commitments. It also needs buy-in from both partners or at least some degree of delegation to RNGesus.

This is why I can’t entirely get behind critiques of “scientism”. Not every deep philosophical riddle has a simple scientific answer - but when one does, it’s pretty great. Thanks to Grognoscente for explaining this so well.

Let me see if I understand this well enough to summarize: the brain separately tracks hedonic state (ending in opioid-ergic neurons) and reward prediction error (ending in dopaminergic neurons). The opioid-ergic neurons remove inhibition (GABA-ergic) on the dopaminergic neurons, allowing them to fire more effectively.

But this still confuses me a little: naively I would have expected the opposite (we get reward for happiness; salience and unpredictability increase it). Does this mean that all surprise is slightly rewarding? How does it separately track positive vs. negative hedonic state?

I felt bad that I didn’t already know all this despite purportedly having studied some neuroscience, so I looked into a paper on the subject recommended by commenter JDK. Now I feel less bad. The paper seems to be arguing something different, saying things like “VTA GABA neurons convey to DA neurons how much reward to expect” and “VTA GABA neurons inhibit DA neurons when reward is expected, causally contributing to prediction-error calculations”.

Is the paper making the case for the opposite of Grognoscente’s comment, where dopaminergic neurons fire in response to any reward, and unpredictability increases the magnitude of it? I’m not sure. I do think the idea of reward center vs. GABA-ergic brake is useful here, even if I can’t get a consistent picture of exactly how it works.

2: Andres of Qualia Research Institute (via email):

Getting the "right fit" for what various serotonin, dopamine, opioid, gaba and NMDA receptors do is challenging - I don't have the final answer or anything close, but I think STV does provide some hints. Your nervous system is constantly creating, maintaining, and retiring internal representations. At QRI we think that the various concentrations of neurotransmitters can change in subtle ways what tools you have available to edit your internal representations. In a super cartoonish way, essentially dopamine reduces the threshold needed to activate a high-frequency consonant state, 5HT2A serotonin activates "pattern breaker" metronomes (as exemplified by the Tracer Tool) and kick-starting an annealing process, and opioids work by activating a generic low-frequency consonance. But the story, of course, is more complex, and the ideal for us is for that complexity to also be explained in terms of STV. Here's an example: dopaminergics have various plateaus - the high-valence ones require both sparse use as well as threshold doses (as you describe). I'd say that to a first approximation, and very schematically, we can divide the state caused by dopaminergics during the come-up as having four plateaus:

(1) mild motivation and mood enhancement

(2) enhancing of cravings and motivation but not yet pleasure or sense of wellbeing (some "hungry ghost" qualia)

(3) satisfaction of the craving and deeper euphoria together with a sense of feeling settled and coherent

(4) overstimulation or, paradoxically, "too much coherence" (which can collapse the information content of experience and/or make you fall asleep)

(just for a general sense of what I'm talking about, say 1-2.5mg dextroamphetamine leads to (1), 2.5-15mg to (2), 15-30mg to (3), and 30mg+ for people with no tolerance, but it can vary a lot).

I think that a lot of people find (2) surprising and a let-down. It's strange that taking more than (1) can actually make you feel worse unless you reach a threshold after which you start to feel remarkably better. Why is that? Here's where the story where the pleasure centers function as a connector hub "bridge" that reduces the distance between different parts of the brain makes a lot of sense. You can work through the effects of different doses in terms of having this bridge activated to various extents. Essentially, when it's sort of "twilight" open, then you might have the unfortunate property of only at times activating coherent states, toggling between dead and flickering, this would essentially create a lot of partial "incomplete" planes of experience, which would be negative in valence.

Metaphorically, it's like you are activating new (chemical) valence shells but can't fill them up - this can actually cause a bias for action, in that the reward from accomplishing tasks might push you over the edge to the euphoric sensations of (3).

At (3) or during good parts of (2) one can for a long while feel very smooth, coherent, "settled", and "unified". You indeed experience a kind of phenomenological coherence that is, in its own way, both (immediately) restful and wide awake. This is a state of high-valence, and albeit it does have some "high frequency" features, phenomenologically it comes with a sense of peace. Indeed, dopaminergic bliss has a default temporal harmony, a fascinating and unexpected ability to relax attention, and a fast buzz that scaffolds pleasant resonant patterns. It's as if a set of very well tuned metronomes are fully active *and* you also have an "orchestra director" that coordinates them effectively. Interestingly, the "comedown" of a stimulant is the result of a faulty or tired director: all of the individual instruments continue playing, but now without coordinating with each other. In other words, the later part of a stimulant trip, as it were, tends to be cranky and irritated even if still quite awake and stimulated. STV explains this: the absence of coordination leads to a loss of the positive valence despite maintaining the same level of arousal. There is, further down the line, an additional secondary comedown where you do feel tired and lethargic, but explaining why that one feels bad isn't very interesting.

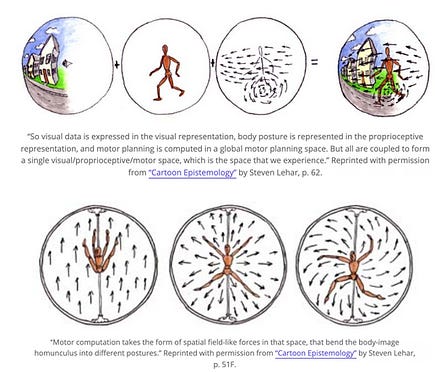

Dopaminergics also distort the geometry expressed in the motor-planning space: it tenses and adds curvature to it so that there is generically more coordinated action. But it also, as a consequence, might restrict the diversity of action-space. Lehar tries to visualize the "motor-planning space" in these images:

Essentially, subjective reward warps the motor-planning space around the thing you believed to have caused the reward. And in general, craving is implemented with tense and warped patterns that restrict movement in directions that don't bring you reward. Extreme addiction might be like being bound in all directions except the one taking you to your addiction. In the mind of an addict, a meth pipe could essentially play the role of a Singularity: under its grip, it becomes the geometric culmination of history as it captures all of your future trajectories.That's one good reason to wait until you're close to death before trying out serious doses of dopaminergics (cf. In Search of the Big Bang).

Related: Steven Byrnes’ objections to the symmetry theory of valence.

3: Excavationist writes:

One neuroscientific perspective on this is that in order for dopamine to track reward prediction *error* (RPE), it is logically necessary that some other piece of neural circuitry track reward prediction *per se*, often called "value." Those of us who think that dopamine is computing RPE on a moment-by-moment basis (the first derivative of value; see Kim, Malik et al., Cell, 2020) therefore generally also believe that some other part of the brain, especially the ventral striatum (aka nucleus accumbens) and perhaps also the prefrontal cortex, maintains an estimate of value that gets updated by dopamine. And indeed, there are dozens of papers reporting that neural firing in these brain regions correlate with value over and above RPE.

I think this explanation differs from the one you offered because rather than seek some other neuromodulator to account for the "companionate love” phase of a relationship, you can just consider that phase to be the psychological correlate of the brain's internal value estimate as it is instantiated in this cortical/striatal circuitry. Though I certainly wouldn't rule out other options, especially intracellular mechanisms in these areas, because neural firing on these very long timescales is dubious.

I answered with “Thanks, this is helpful (though I had always thought nucleus accumbens *was* "reward center", is it doing both these things?)”, and they continued:

I think it's fair to call the nucleus accumbens (NAc) the reward center, but not for the reason most people think.

Most people think this is the case because when you put subjects in an fMRI scanner and have them do tasks where they get reward or learn cues that are associated with reward, you robustly get RPE-related BOLD activity in the NAc, and only rarely/more weakly in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which contains the dopamine neurons that project to the NAc. So when you see those nice fMRI maps, the NAc is lit up in red. But the physiological basis of this fMRI signal is hotly debated (for example, it could represent primarily synaptic input rather than actual neuronal firing, especially in a GABAergic circuit like the striatum), and in single-unit recordings in mice, rats, and monkeys, it is unequivocal that dopamine neurons in the VTA show much more RPE signaling than the striatum.

That said, it is also true that (1) NAc neurons correlate strongly with value and also respond to some extent to rewards, predicted and unpredicted; (2) cocaine or amphetamine in the NAc (and another region of the ventral striatum called the olfactory tubercle), which dramatically elevate dopamine levels, elicit robust responses; and (3) in the context of the "liking vs. wanting" framework you allude to, Kent Berridge and others have argued that the NAc contains a "hedonic hotspot", along with closely linked regions like the prefrontal cortex and ventral pallidum. This is an operational definition meaning that when you infuse opioid receptor agonists into said region, the animals react with pleasure, and conversely if you lesion/block activity in these areas, they don't show these behaviors as much, or even start showing defensive behaviors.

Excavationist also says:

Lastly, on the abusive relationship point, you might be interested (or perhaps you already know) that BF Skinner famously observed that "variable ratio" reward schedules lead to greater responding/addiction than other kinds of schedules. I guess this is what you're getting at when you say, "Everyone has some weird function that doesn’t correspond to normal addition, and maybe for some people dating a person who gives good vs. bad signals exactly 50% of the time is the only way to get that function in the black." I would amend this slightly to say that some people are more sensitive to the volatility (which is very much a function of RPE directly), and others to the value itself (the integral of RPE).

This is a weird theory, because (IIUC) it’s sort of suggesting that there are all these electrical-mathematical things going on in the brain, and which one is “the reward function” or feels like “happiness” is underdetermined and has to be learned!

4: Demost_ writes:

"Any neuroscience article will tell you that the “reward center” of the brain - the nucleus accumbens - monitors actual reward minus predicted reward."

This claim is way too strong.

What is correct:

Reward Prediction Error (RPE) is one of the main theories on what the reward center (nucleus accumbens NAc) does. There are many situations and experiments in which this explanation fits nicely.

What is also correct:

There are many situations in which RPE does *not* fit nicely. The discussion on what the reward center really does is far from settled.

I can highly recommend the paper "Dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens core signals perceived saliency" by Kutlu et al. from last year for a different opinion. It's really well written and contains great experiments. The authors suggest that the reward center does not represent RPE, but saliency. They summarize their work with the following four points:

- NAc core dopamine only mimics reward prediction error in select reward contexts

- RPE does not model dopamine release during negative reinforcement

- Dopamine signaling in the NAc core does not support valence-free prediction error

- NAc core dopamine tracks valence-free perceived saliency in all conditions

This paper will not be the end of the debate. But RPE is not the end of the debate either.

UPDATE: After reading the full post (great post!), I really have to find some time to re-read the study by Kutlu et al., put it next to the post, and see how the post aligns with their experiments. The result might be quite interesting.

I apologize for implying anything in neuroscience was ever settled, straightforward, or comprehensible. I will strive to do better in the future and to make amends to any neuroscientists who were harmed by this ignorant and offensive statement.

5: Scott writes:

When I was in graduate school, I was a facilitator for domestic violence batterers intervention psychoeducation groups. (A mouthful, I know). It was the California-mandated program for DV offenders. I did this for about 3 years, and had nearly 4000 clinical contact hours with this cohort.

After deciding that my preferred treatment modality was psychodynamic and I began using (mostly Kleinien) interventions, I started giving this spiel to the guys.

"You could walk into a room with 500 women. 499 of them would be mostly healthy, insightful well-boundaried, nice girls who would make wonderful supportive wives and mothers. Not perfect by any means, but they would be invisible to you. The one left would be a crazy borderline with all kinds of unhealthy personality traits and maladaptive life skills and the two of you would be attracted to each other on a subconscious level like flies on sh!t. Until you spend about 2 years in therapy figuring out what that is about (hint, its probably your mom) this pattern will continue until you die."

That's how I conceptualize your patient with the abusive wife. You pointed out that people have all kinds of rubrics that do not have to add the prediction/error equation to zero. Personality pathology and the way they interact in relationships account for a lot of that.

And yes, because those patterns are so difficult to dislodge, he is more or less doomed to a miserable life. Although, like you, I never say stuff like that to them.

This isn’t exactly saying anything new, but I am filled with a desire to hear more stories about these sessions, which sound fascinating. This Scott says he is a “forensic psychologist in private practice” and has just started a Substack called “The Age Of Subjectivity”, so hopefully I’ll get what I want.

6: Pope Spurdo writes:

"Poly people talk about 'new relationship energy' - if you start a relationship with a new person, you will be passionately into them for a few months, usually at the expense of all your other relationships, before settling back down again. Most poly advice books will give you tips for managing it, which mostly boil down to for God’s sake, don’t take your feelings seriously and deprioritize all your other relationships because this new one is so much better."

This advice works for literally everyone who's in that heady early stage of romance. I am reminded of what @AuronMacintyre said on Twitter: "Periodically progressives reverse engineer healthy sexual behavior and act like they've discovered Atlantis."

I want to defend associating this advice mostly with polyamorous people. If you’re monogamous and you start a new relationship, and it’s great, and you’re really happy, good for you. The advice you need is “enjoy it while it lasts”. Maybe a side of “be careful before moving across the country to be with this person, or getting married”, but I feel like this aspect is well-known and common sense.

If you are polyamorous, you have the additional problem that you might have already committed to your wife Alice, and then decided to have a fling on the side with new partner Barbara. But now Barbara is so much more exciting than Alice that you start worrying you have made a mistake, Alice was the wrong choice, you and Barbara are soulmates, and you should get a divorce and marry Barbara instead. Many such cases.

I guess this happens to monogamous people too when they have affairs, but it’s already partly covered under the “don’t have affairs” advice, and people who violate that advice are harder to have sympathy for. I feel worse when it happens to polyamorous people who were trying to follow the rules and do things right.

They also write:

> "In contrast, on February 1 you have $1 billion more than on January 31, but because you predicted it would happen, it’s not that big a mood boost."

From personal experience, I disagree. Here's what I recall about selling a property a few years ago:

(1) When the house went under contract, then passed inspection, I was happy knowing that I'd be getting a lot of money at closing in a few weeks. I even got about 3% more than my realtor thought I should ask for, so I felt vindicated.

(2) When the money actually hit my bank account and I saw a six-figure deposit, I was _ecstatic_ to the point that I kept logging in to online bank all day just to stare a balance that was at least ten times greater than it had ever been before. Felt freaking awesome.

7: Other commenters see it more my way, eg Gary Waldo:

Last year I was lucky in that I earned around 5M USD in selling a start up.

I remember in the week before the transaction I could get almost euphoric and giddy thinking about about the money and by average happiness level definietely increased.

When the money arrived in my bank account however, it was almost anticlimaxic - it barely had any impact on my mood. Now, 1 year later my general happiness level was not noticably high than pre-5MUSD - that is, until I quit my job.

This definitely had a great impact on my happiness level - not because I hated or even disliked my job, but having complete ownership of my days really feel great. This is also mentioned in The Psychology Of Money by Morgan Housel - one of the very few lifestyle changes which may be achieved through wealth which correlates with an increased degree of happiness is being able to wake up and knowing you can do whatever you want this day.

8: Designer-Shift-7442 writes:

"how come predicting you would get the money mostly cancels out the goodness of getting the money, but predicting you would get the Ferrari/dinner doesn’t cancel out the goodness of the Ferrari/dinner?"

We care so much about money, we tend to forget: Money is primarily a *means* to things that are desirable, it's not desirable thing in itself.

Predicting you would get the money mostly cancels out the goodness of getting the money?because Money already *is* a prediction. If I have a million dollars, that's a statement about my future. It means that, over time, I can trade that money for a million dollars worth of things I want.

Knowing that I will soon have a million dollars in the bank is not that different than having a million dollars in the bank, especially if I plan on spending it over a long period of time. They are basically the same situation: i am happily anticipating future pleasures, security, etc, maybe just on a slightly different time frame.

Knowing I will eat cake tomorrow is a completely different from eating cake.

I like this idea of money as already being a prediction, and predicting money just being a prediction of a prediction.

9: Steve Byrnes writes:

One thing that might help in certain parts of this post is to split up the concept "prediction" into two different concepts, "visceral expectations" versus "intellectual predictions". "Visceral expectations" are related to valence, aversion, desire, sweating, goosebumps, all that stuff, whereas "intellectual predictions" are the things that you consciously believe.

I think that intellectual predictions can impact visceral expectations a little bit—more than zero—but definitely not completely. The two can stay discrepant. For example, if you've never done cocaine, and you read in a textbook that cocaine feels really intensely good, and you completely sincerely believe the textbook, then now you have a very strong (intellectual) prediction that cocaine feels good. But you still only a weak visceral expectation that cocaine feels good. So you don't suddenly start craving cocaine the way an addict does. Then maybe you actually try cocaine yourself, and NOW the visceral expectations regarding cocaine get strongly updated.

Anyway, I think the P of RPE is visceral expectations, not intellectual predictions.

Agreed. This is also why I stressed how weird it is that eg you still “predict” your partner’s presence months after they died; these are visceral expectations. not conscious ones.

10: Vorkosigan1 writes:

Maybe rich people are happier than poor people because they don't have to deal with sh!t all the time. You know, that stuff about the cognitive burden of poverty, etc.

As some commenters pointed out, I’m a bit skeptical of some of those cognitive-burden-of-poverty studies qua cognition. But I think this is a good point. Being poor is a state where you are open to unpleasant surprises. If something breaks, it might mean hours spent trying to repair it, or months spent without a necessity, whereas a rich person would just shrug and get a new one. You might have an older/worse car that breaks more often, or an older/worse house that needs more maintenance. Your job might be able to put more sudden demands on you without you having alternatives or exit options.

In contrast, being rich is a state where you are open to pleasant surprises. If you see an exciting new product or experience, you can just get it and enjoy it. Sometimes people will offer you nice things for free in order to gain your goodwill.

I don’t know if this is special pleading or I’m biased towards noticing the ways this is true because it would be elegant, but I do think this could explain some of why the hedonic treadmill isn’t perfect - with some of the more neuroscience-y stuff towards the top of this post explaining some of the rest.