|

Your weekly 5-minute read with timeless ideas on art and creativity intersecting with business and life͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

| Welcome to the 121st issue of The Groove. If you are new to The Groove, read our intro here. If you want to read past issues, you can do so here. If somebody forwarded you this email, please subscribe here, to get The Groove in your inbox every Tuesday. Find me here or on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook. |

| WHY REMAINING FLEXIBLE SHAPES TRUE INNOVATION |

| Creativity is the precursor of innovation. It all starts with an idea, then we test, refine, remix, and elevate what already exists. With a lot of experimentation, sometimes we can innovate and open up new paths for us and for present and future generations. These two intertwined aspects are not only vital for anyone who’s ambitious and driven in their professional pursuits but are also the lifeblood of any business: companies (regardless of their industry or size) that stop innovating tend to disappear. For many of us, the relentless quest for efficiency and reacting to hasty and continuous changes has thwarted the experimentation phase that leads to innovation. In other words, we tend to falsely believe that our tried-and-true formula will always deliver for us. But what always works is an openness to testing, failing, pivoting, and probing new things. Man Ray, one of the greatest artists innovators of the 20th century, proved this to us with four major themes that were present in his life. |

|

|

Man Ray in his studio in Paris.

|

|

| Our egos want to protect us from perceived harm, including the fear of failure. We tend to form ideas early in our lives of who we are, what we want to be and how to get there. Our vital understanding comes from knowing that the ego is rigid and one-dimensional and will do whatever it takes to keep us exactly where we are. This is what stops us from seeing opportunities and being flexible enough to explore them. The eldest child of Russian immigrants, Philadelphia-born Emmanuel Radnitzky moved to Brooklyn when he was seven, and by the time he was twelve he had changed his name to Man Ray to avoid being the target of antisemitism. After developing his skills as a painter at the National Academy of Design, the Art Students League and the Ferrer School, he met and befriended Marcel Duchamp, who had been living in New York since 1915. Open to experimentation and willing to leave behind what he’d learned in school, Man Ray fell hard for Duchamp’s Dadaist ideas, the anti-art movement rejecting logic, reason and aesthetics. After several attempts and failures at showing Dada art, Man Ray realized that New York wasn’t ready for this. Undeterred, he moved to Paris in 1921. Instead of letting this be a blow to his ego, he gave his ego a run for his money, moving countries and being open to change and opportunities while assimilating into a different culture. |

| Stay Open to Saying “Yes” |

|

|

Man Ray, Peggy Guggenheim wearing a Poiret dress (1924).

|

|

| How many times do we close ourselves off to great opportunities because we have this relentless idea that “this is not what I do”? You don’t have to say yes to everything, but make sure you do evaluate why you say no to something before slamming the door in its face. Man Ray’s heart was set into being a painter, and in 1915 he bought a camera merely to record his paintings. He was so good at photographing objects that when he moved to Paris, Francis Picabia hired him to take pictures of his own work. This basically gave Man Ray the money to survive his initial phase in another country. Picabia’s wife, Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, introduced Man Ray to couturier Paul Poiret, who made him a job offer recognizing his talent even though he had no previous fashion photography experience. Poiret needed someone to create unconventional imagery with his models, and Man Ray was exactly the kind of person who could do that. Being a fashion photographer 100 years ago was not easy, but Man Ray said yes immediately. |

| Be Attentive to Happy Accidents |

|

|

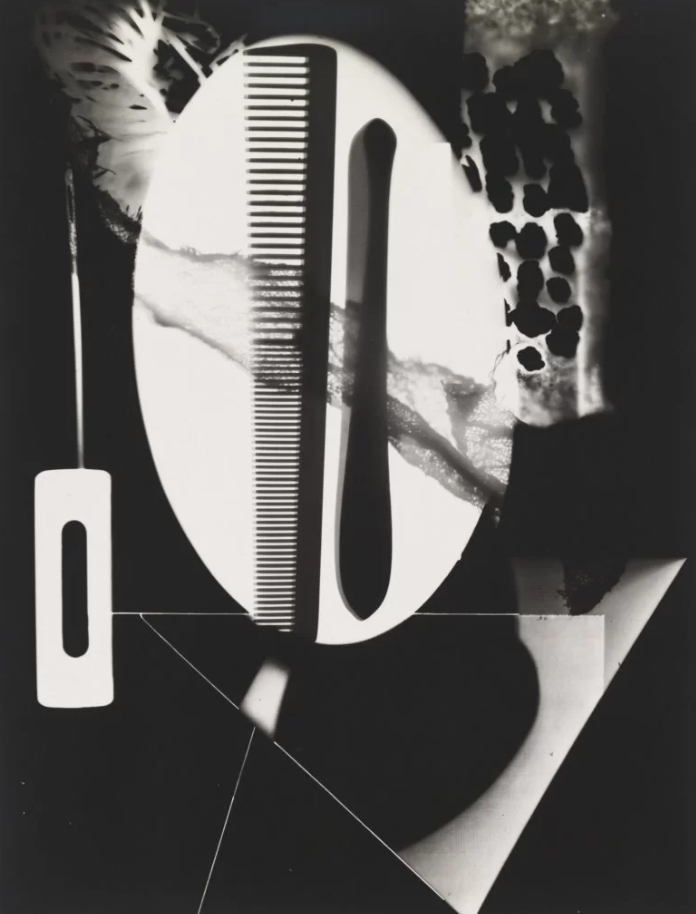

Man Ray, Untitled, rayograph, 1922.

|

|

| One of the things I consistently stress to people who ask how to find more business opportunities for themselves, is to slow down intentionally and pay close attention to your surroundings. It’s the same if you are looking for a creative breakthrough. So many seemingly inconsequential and “normal” events are in fact the trampolines for summersaults. As Man Ray told the story, it was in the course of printing pictures from a fashion shoot for Poiret that he stumbled on the process he first dubbed "rayo-graphs" after his own name. In his hotel room at night, he would develop his glass plates (before he used film), and looking to make a contact print, he placed the developed plate on photosensitive paper, turned on the light, then submerged the paper in chemicals. And voilá, the image would appear after a few seconds. But on one occasion, a sheet of paper not exposed to a negative ended up in the tray. Realizing his mistake, he got annoyed and absentmindedly placed a funnel, a measuring flask, and a thermometer on it and turned on the light. As he watched, the uncovered parts turned black, and the covered sections became white and gray. Flabbergasted, he did it several more times with other sheets to make sure he was right in his experiment. To his amazement, he didn't even need to wet the paper, all he needed to do was arrange the objects and turn on the light for a few seconds. These rayograms were one of the greatest innovations in photography, and the Dadaists immediately loved and praised them as true to their ideals. Man Ray was on a roll and in 1922, four rayographs were published in Vanity Fair. When the Museum of Modern Art in New York staged its groundbreaking show in 1936, Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, a 1923 rayograph graced the catalogue cover. |

| Let Your World Become Your Lab |

|

|

Man Ray, Le Violon d'Ingres (1924).

|

|

| Like a mad scientist, Man Ray conducted a multitude of chemical and optical experiments, testing the elasticity of light and its unrealized effects on light-sensitive paper. “I deliberately dodged all the rules,” he said. “I mixed the most insane products together, I used film way past its use – by date, I committed heinous crimes against chemistry and photography, and you can’t see any of it.” After the rayograms, he refined the technique of solarization and continued to work with the greatest fashion designers, cosmetic houses and magazines until the 1940s. His strange compositions, plays of light and shadow, solarizations, colorizations, and other technical experiments generated dreamlike images that had never been seen before. He changed and influenced fashion photography forever. While his paintings are excellent, Man Ray’s photos are revolutionary. I don’t think he would have expected that last May, Le Violon d'Ingres (1924), depicting a nude Kiki de Montparnasse's back overlaid with a violin's f-holes, would have sold for $12.4 million, setting a new world record as the most expensive photograph ever sold at auction. Her voluptuous body, with its curvaceous posterior, to Man Ray resembled a violin or cello. In the darkroom, he covered a sheet of printing paper with a stencil in which he had cut out the forms of the f-holes. He exposed that to light, much as he did when making a rayograph. Removing the stencil, he superimposed the negative of Kiki, so that the f-holes are burned onto her back. It is true that he never wanted to be known just as a photographer but at the end of his life, four years before his passing, he was captured in a video interview asserting that photography was an important part of his practice. He rejected the idea of “admirable craftsmanship” in favor of becoming a “practical dreamer” and closing with the ultimate thought on openness and flexibility: “I never knew what I was doing until I was done.” And you, as a practical dreamer, can do the same: every week devote a percentage of your time to engage in low-risk things that you have no clue how they will turn out. This is valuable experience that will accumulate, and I bet that in no time, you will have new stimulating results to play around with and maybe, even disrupt things. |

| UNLEASH YOUR CREATIVE GENIUS I’ve put together a free webinar for those of you who are not members of my online course, Jumpstart. If you’d like to watch it, please register here (it’s on auto-repeat every 15 minutes once you have registered). |

| HOW CREATIVITY RULES THE WORLD My book was chosen by the Next Big Idea Club as one of the top books of creativity of 2022! Have you gotten yours yet? If you enjoy this newsletter you will love my book! How Creativity Rules The World is filled with practical tools that will propel and guide you to help you get any project from an idea to a concrete reality. It’s in three formats: hardcover, eBook and audiobook. |

| TEDX TALK Have you already watched my TEDx Talk: “NFTs, Graffiti and Sedition: How Artists Invent The Future”? I share three lessons I have learned from artists that always work for anyone in their careers. Watch it here. |

| Thank you for reading this far. Looking forward to hearing from you anytime. There are no affiliate links in this email. Everything that I recommend is done freely. |

| If you liked what you read here, forward to a friend with an invitation to subscribe here. |

|

|

|