Net Interest - Broker Rivalry

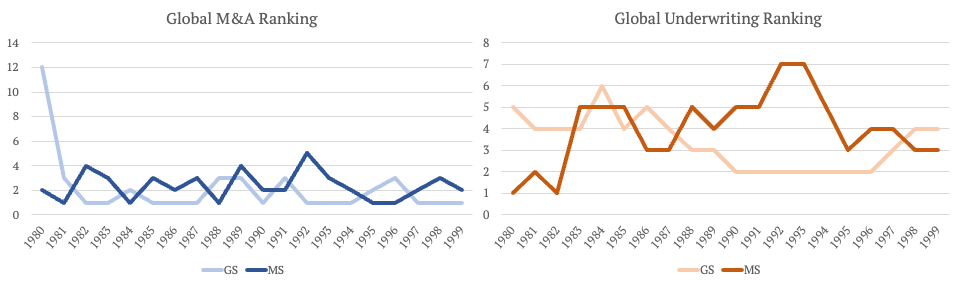

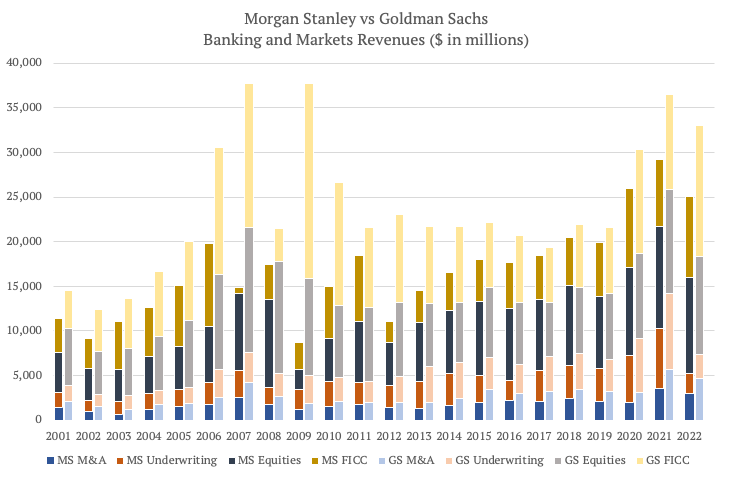

Welcome to another issue of Net Interest, my newsletter on financial sector themes. This week I take a look at the rivalry between Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. For years Morgan Stanley was on top, then Goldman Sachs took over, now it may be Morgan Stanley’s time again. Paying subscribers get access to all my underlying data as well as comments on the Fed discount window, industry headcount cuts and Japanese banks. To join them and unlock all that extra content, you can sign up here: If you are steeped in American folklore, you probably know about the feud that raged between the Hatfield and McCoy families. If not, it’s quite a story. It begins at around the time of the Civil War. The Hatfields were a wealthy family with a large timbering operation along the Tug Fork in West Virginia. The McCoys were farmers with land interests on the other side of the river in Kentucky. Tensions had simmered between the families for years but when the McCoys suspected that the Hatfields had stolen one of their pigs, they tipped into violence. Convinced the pig was his, Randolph McCoy took the matter to the local Justice of the Peace but lost. The key witness, a relative of both families, was later found dead, killed by two McCoy brothers. The feud escalated after Randolph’s daughter, Roseanna, became romantically involved with one of the Hatfields, leaving her family to live with them. It wasn’t the best foundation for a relationship. The McCoys tried to have him arrested on outstanding bootlegging charges and although he escaped, the couple didn’t reconcile; she was abandoned to give birth to their baby daughter alone. Not long after, three of Roseanna’s brothers got into a fight with one of the Hatfields after he’d been drinking in Blackberry Creek, Kentucky. Ellison Hatfield was stabbed 26 times and finished off with a shotgun. The brothers were arrested but the Hatfield family organised a large group of vigilantes to intercept them. They were tied to pawpaw bushes and executed, a total of fifty shots fired. Soon, another McCoy was ambushed by members of the Hatfield clan. The feud reached its peak during the 1888 New Year’s Day Massacre. In the dark of morning, members of the Hatfield family raided the McCoy cabin and a firefight ensued. Randolph McCoy escaped, but two of his children were killed and his wife beaten. With his house burning, Randolph and his remaining family escaped into the wilderness. The murders prompted Kentucky’s governor to authorise a special force to cross into West Virginia to track down the culprits. Several were killed in the process and after a showdown – the Battle of the Grapevine Creek – eight were arrested and brought back to Kentucky for trial. The case required the intervention of the Supreme Court on the grounds that the interstate extradition was illegal but the court ruled that the men could be tried. They were found guilty and one was sentenced to death. Between 1880 and 1891, the feud claimed more than a dozen members of the two families. It was a bloody episode with no winners. ¹ Which makes it an odd metaphor for the competitive environment in investment banking. Yet in his recent memoir, former CEO of Morgan Stanley, John Mack, describes his relationship with Goldman Sachs thus: “Our firms were sworn enemies – the Hatfields and the McCoys.” He may not have been exaggerating. Throughout the book, Mack refers to Goldman Sachs as his “archrival”. He describes his foray into China and the help he received from his local banker there: “In the war – and believe me, it was a war – to get the best business and thwart Goldman Sachs and other investment firms in China, she was the heavy artillery.” This week, Morgan Stanley won its latest battle over Goldman Sachs. Both firms reported their earnings for last year and they stood in marked contrast. It was a challenging year for the industry but while Goldman Sachs’ revenues were down 20%, Morgan Stanley’s were down only 10%. Morgan Stanley generated a 15% return on equity; for Goldman, it was 11%. On their earnings calls, Morgan Stanley’s CEO concluded: “The firm did what it was supposed to do with our more stable Wealth and Investment Management businesses offsetting declines in Institutional Securities.” By contrast, Goldman’s CEO admitted, “Simply said, our quarter was disappointing and our business mix proved particularly challenging.” Morgan’s AdvantageWhen Morgan Stanley was founded in 1935, Goldman had already been going for 66 years. But it had fallen on hard times. Its reputation was shattered by its sponsorship of the Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation, an investment trust that collapsed following the Wall Street Crash. And the market environment left little need for Wall Street services – “particularly services from a midsize Jewish firm with few distinctive capabilities,” the firm’s strategy consultant later wrote. In the period between the 1929 crash and the end of the Second World War, Goldman Sachs was profitable in only eight out of sixteen years. Many partners owed the firm money because their partnership income was less than the draws that their families needed to get by. The year Morgan Stanley was founded, Goldman did only three debt placements, totalling less than $15 million. Morgan Stanley came out strong. It was set up by J.P. Morgan & Co. partners Henry Sturgis Morgan (a grandson of J.P. Morgan), Harold Stanley and others after government legislation required American commercial and investment banking businesses to be separated. The partners brought their J.P. Morgan clients with them. In its first year of operations, the firm captured a 24% market share ($1.1 billion) in public offerings and private placements. Unlike Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley did not have to fight prejudice. Reflecting on his time as a banker, future Goldman Sachs CEO Hank Paulson said that even “in the late 1970s, you’d have a lot easier time doing business if your name was Morgan Stanley.” When Morgan Stanley did eventually promote a Jewish partner, a senior member of the firm called his counterpart at Goldman. “We’ve just made our first Jewish partner!” “Oh, Perry,” retorted Weinberg without a pause, “that’s nothing. We’ve had them here for years!” By 1947, Morgan Stanley was firmly entrenched as the most successful firm on Wall Street. The honour was crystallised in the firm being named lead defendant in an antitrust lawsuit the US government brought against the industry. “US v Henry S Morgan et al” contended that between 1915 and 1947, seventeen firms created “an integrated, over-all conspiracy and combination by which [the banks] developed a system to eliminate competition and monopolize the cream of the business of investment banking.” Goldman was grateful just to be listed at all. In the years that followed, both firms expanded widely. When retail investors gave way to institutional investors as major participants in equity markets in the 1950s, Goldman developed a block trading business to serve them. The firm began charging for M&A advice and launched a bond business to sit alongside its legacy commercial paper business. Morgan Stanley did likewise. In the late 1970s, it added a new division practically every year: portfolio management in 1975, government bond trading and automated brokerage for institutions in 1976, and retail brokerage for high net worth individuals in 1977, following an acquisition in San Francisco. In M&A advisory work, Goldman eventually caught up with Morgan Stanley. Recognising how hard it would be to dislodge Morgan Stanley as investment banker to major blue-chip corporations, it focused instead on smaller companies and in particular takeover targets. It launched its “tender defence” unit in the early 1970s and when the M&A boom took off in the 1980s, it was well placed. In 1981, Morgan Stanley still led Wall Street with $40 million in merger fees, doing a third of all deals – but Goldman Sachs had entered the top three. Yet in the business of securities underwriting, the gap was still evident. Following a series of bond deals for Ford, Sears Roebuck and General Electric in 1956, Goldman broke into Wall Street’s top ten. But in almost every year between 1935 and 1981, Morgan Stanley reigned supreme. That began to change in 1983 with the introduction of a new rule – the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Rule 415. The rule allowed public companies to register new securities but then shelve the public offering for up to two years. Companies could therefore make a public offering at precisely the point when they need the money, or when market conditions are favourable, with a minimum of expense and effort. The rule favoured those banks with the capital to take big blocks and unload them quickly. Morgan Stanley plummeted to fifth in the league table of underwriters. However, alongside Goldman, it did benefit from a consolidation of market share. Having handled a quarter of new debt prior to the introduction of Rule 415, six firms underwrote almost half afterwards. As a result of both its expansion and the need for more capital to support its core business, Morgan Stanley decided to IPO. “The faster we expanded – the more risk we took – the sooner the more wary partners opted for the exit ramp,” wrote John Mack. “Previously, such partners were 100 percent comfortable at the firm… By the mid-1980s, the subtext at every retirement party was how much capital was leaving the building. The more partners who departed, the less growth we could afford. We needed more – and a more permanent source of – capital. That was the key. The solution? To go public.” In 1986, the firm sold 20% of its stock to the public, raising around $300 million for the firm. Issued at $56.50, the stock jumped to $71.25 on its first day of trading. “I made more money in six and a half hours than I had ever dreamed of making over a lifetime.” For thirteen years after, Goldman remained steadfastly private. Initially, the firm didn’t see it as a competitive disadvantage. In the early 1990s, Goldman clawed its way up from a top five global underwriter to a top three underwriter. In the less capital-intensive M&A business it remained top three, alongside Morgan Stanley. But in 1997, Morgan Stanley merged with Dean Witter to form a larger, more diversified financial services business. “Things had gone pretty well for Morgan Stanley,” wrote Mack. “But my view was that this momentum would eventually sputter out. We needed to keep innovating; to hunt down new opportunities.” In particular, the merger gave the firm a more steady income stream. “Because of credit card transaction fees and the recurrent fees the company earned on its mutual fund business, it covered its overhead within the first four months of the year. Everything from May 1 on was profit. By contrast, Morgan Stanley’s business, based on dealmaking and trading, was unpredictable. We didn’t cover our overhead until September, or even later.” The merger left Goldman in a strategic dilemma – it lacked the currency of a public listing to make its own acquisitions, and it was reliant on its partners for capital. “Goldman was always a cut above the rest, but now the firm is being run ragged by Morgan Stanley Dean Witter,” reported the Financial News. Goldman, in turn, decided to IPO. It sold an eighth of the company and raised $3.6 billion. On its first day of trading, Goldman stock jumped from $53 to $76 before closing the day at $70. The next few years marked a divergence of fortunes. The Dotcom crash of 2000 impacted the firms differently. Under the leadership of Phil Purcell, formerly CEO of Dean Witter, Morgan Stanley took on less risk. “As Phil drew back, Goldman Sachs and J. P. Morgan leaned in, looking for the opportunities that a crisis always creates,” wrote Mack. “They made tremendous inroads in areas where Morgan Stanley had once dominated. To my mind, we lost focus and commitment – and along with it, our leadership position on Wall Street.” Purcell and Mack engaged in a very public power struggle, culminating in first Mack leaving and then Purcell leaving, before Mack returned. Hank Paulson, now CEO of Goldman Sachs, thought the IPO helped his firm compete. “We went from being the medium-sized firm to being a large firm and we kept the best attributes of the culture. We went from being a firm where we were behind Morgan Stanley and right there with Merrill Lynch to being a firm that was clearly the global leader.” ² Present Day RivalryFor most of the next 20 years, Goldman Sachs remained dominant. In underwriting, it generated more revenues than Morgan Stanley every year bar four. In M&A advisory, its revenues were consistently around 50% higher than Morgan Stanley’s. And in sales and trading, it dominated too, earning more than Morgan Stanley in fixed income and – until 2014 – in equities. Yet rather than compete head-on, Morgan Stanley has increasingly allocated resource to other, less capital-intensive areas, notably asset management and retail brokerage. Its acquisitions of ETrade (2020) and Eaton Vance (2021) enhance the “steady income stream” that John Mack had coveted at Dean Witter years earlier. “These are core businesses with scale in major markets that are, on the whole, more balance sheet-light and benefit from more durable fee-based revenues. We continue to invest in these areas to drive future growth,” current CEO James Gorman said on his earnings call this week. As a result, Morgan Stanley is now able to generate more revenue per unit of balance sheet than Goldman Sachs. Having generated around the same, as a ratio of risk-weighted assets, in 2010, Morgan Stanley’s revenues now represent around 12.7% of risk-weighted assets, compared with 7.0% at Goldman Sachs. It's a strategy the firm wants to run with. In the past three years it has accumulated nearly $1 trillion of net new assets from customers, “showing a clear step change from prior periods and marking Morgan Stanley as a leader across our peer group as an asset accumulator,” according to Gorman. Extrapolating the trend and layering in some asset appreciation, the firm believes it can get to $10 trillion of client assets over the next few years. Its wealth and asset management businesses already represent over half group revenues and Gorman’s goal is to increase that:

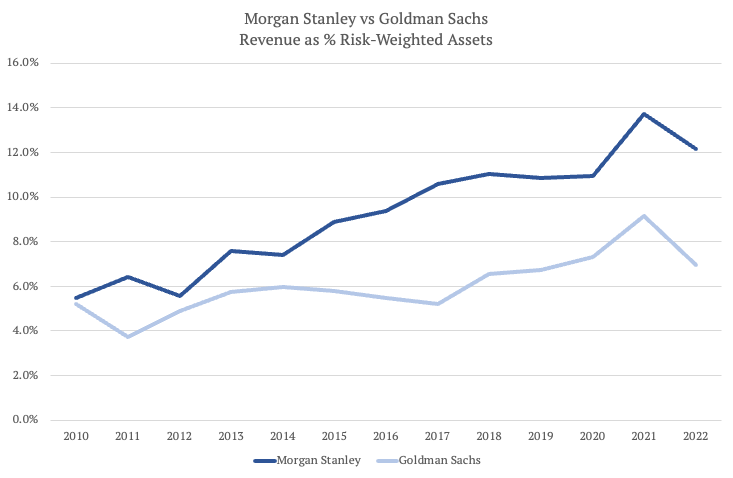

At the same time, Morgan Stanley is prepared to give up on some upside in fixed income in the event markets there improve. “I mean, we’ve never tried to be the FX, EM shop. We’ve never had the global rates trading, FX trading, macro businesses that some of the correspondent-driven commercial banks have had, the HSBCs and Citis. And that's a business model, just different,” said Gorman on his call. He currently pegs his market share at 10% in fixed income (compared with 15% in banking and 20% in equities) but recognises that “arithmetically, given our share relative to the others, we wouldn’t grow as fast.” Goldman, too, has pumped resources into its asset and wealth management business, but in a more capital intensive way, as cover for some of the principal investing business it used to do. It’s now making a shift – “from a balance sheet-intensive asset management business to a client-oriented fee-based business,” according to its CEO, David Solomon. It also invested very heavily in more consumer-facing businesses, a strategy we discussed in Reinventing Goldman Sachs two years ago. That strategy now looks expensive, having racked up $3.8 billion in pre-tax losses over the past three years, a key driver for the slump in profitability in 2022. Going forward, Solomon identifies three strategic priorities for his firm: growing management fees in the Asset & Wealth Management business; maximising wallet share and growing financing activities in the Global Banking & Markets business; and scaling the new Platform Solutions business to deliver profitability. Success may help it catch up again with Morgan Stanley, but what 2022 shows is that in the long-running feud between the two, Morgan Stanley is once again on top. Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the “Like” button. Better yet, join the community by signing up as a paid subscriber! 1 I used Wikipedia and The Herald Dispatch as my sources, but this is a helluva rabbit hole to go down. It turns out that nobody knows anything. 2 Even after it assumed top-spot, the rivalry persisted. When conflicts of interest between research and banking were uncovered across the industry by New York State attorney general Eliot Spitzer and the SEC, Goldman’s Hank Paulson called in Bob Steel, head of his equities division. “Bob, your job is to get a settlement that makes Goldman Sachs look okay – okay compared to Morgan Stanley. It may well be that our analysts did worse things than theirs did, so your job is clear: Make sure our firm [fares] no worse than their firm.” Steel “won.” He got a fine of $110 million for Goldman Sachs, while Morgan Stanley paid $125 million. You’re on the free list for Net Interest. For the full experience, become a paying subscriber. |

Older messages

The Bank that Never Sold

Friday, January 20, 2023

Plus: Net Interest Margins, Frank, BlackRock

Insuring the Unknown

Friday, January 6, 2023

Plus: Blackstone, Crypto Banks, Citadel Securities

Generation Rent

Friday, December 9, 2022

Plus: Trafigura, Sberbank, FlatexDEGIRO

The New Conglomerates

Friday, December 2, 2022

Plus: S&P Global, Financial Services Comp, Blackstone

Printing Money and More

Friday, November 25, 2022

Printing Money, Equity Research, Petershill, Credit Suisse

You Might Also Like

Longreads + Open Thread

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Personal Essays, Lies, Popes, GPT-4.5, Banks, Buy-and-Hold, Advanced Portfolio Management, Trade, Karp Longreads + Open Thread By Byrne Hobart • 8 Mar 2025 View in browser View in browser Longreads

💸 A $24 billion grocery haul

Friday, March 7, 2025

Walgreens landed in a shopping basket, crypto investors felt pranked by the president, and a burger made of skin | Finimize Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 8th in 3:11 minutes.

The financial toll of a divorce can be devastating

Friday, March 7, 2025

Here are some options to get back on track ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Too Big To Fail?

Friday, March 7, 2025

Revisiting Millennium and Multi-Manager Hedge Funds ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The tell-tale signs the crash of a lifetime is near

Friday, March 7, 2025

Message from Harry Dent ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

👀 DeepSeek 2.0

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Alibaba's AI competitor, Europe's rate cut, and loads of instant noodles | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 7th in 3:07 minutes. Investors rewarded

Crypto Politics: Strategy or Play? - Issue #515

Thursday, March 6, 2025

FTW Crypto: Trump's crypto plan fuels market surges—is it real policy or just strategy? Decentralization may be the only way forward. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What can 40 years of data on vacancy advertising costs tell us about labour market equilibrium?

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Michal Stelmach, James Kensett and Philip Schnattinger Economists frequently use the vacancies to unemployment (V/U) ratio to measure labour market tightness. Analysis of the labour market during the

🇺🇸 Make America rich again

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

The US president stood by tariffs, China revealed ambitious plans, and the startup fighting fast fashion's ugly side | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March

Are you prepared for Social Security’s uncertain future?

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

Investing in gold with AHG could help stabilize your retirement ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏