Does it matter that central banks are losing squillions?

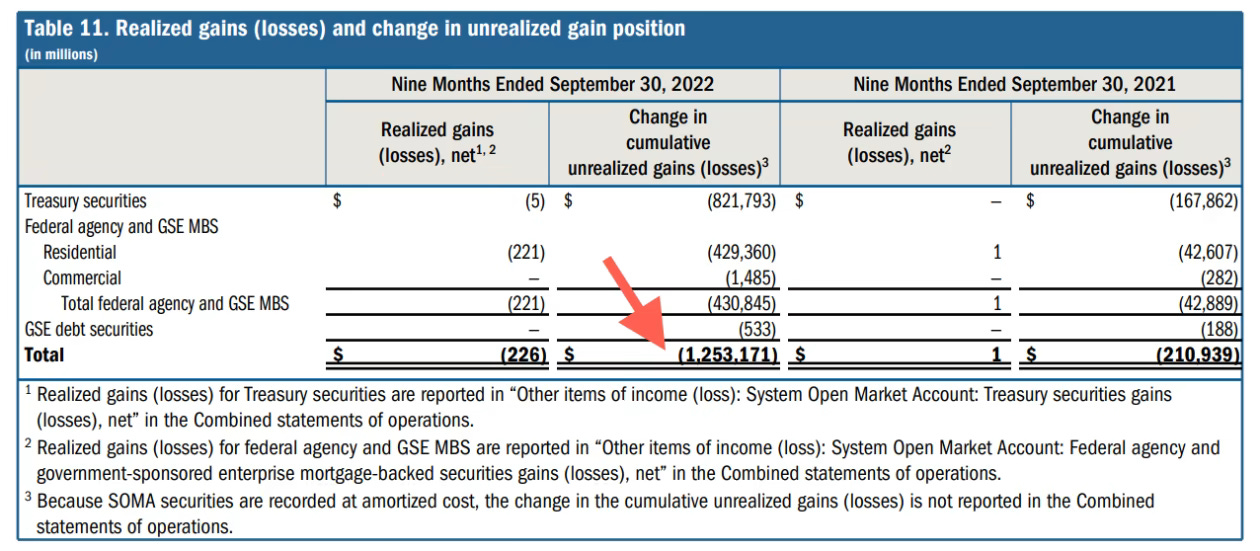

Originally published in the Financial Times on February 1, 2023. Take the Federal Reserve, for example. Chair Jay Powell had the Fed gobbling up almost every bond in sight ($4.5tn worth) at the start of the pandemic while rates were already close to all-time lows. There was only one way for yields to go. What was he thinking? Unsurprisingly, the Fed’s portfolio has stunk. The Fed’s last financial update, in September 2022, reveals paper losses of almost $1.3tn during the first three quarters of that year. Since then, 10-year Treasury yields have round-tripped from around 3.5 per cent to 4.25 per cent and back, suggesting the losses may be similar today. And that’s just the Fed’s mark-to-market losses on its portfolio, the SOMA (System Open Market Account). The Fed’s net income — mainly, the difference between what the Fed earns on its bond portfolio, and what it pays out to commercial banks on their reserves at the Fed — has also turned deeply red. The US central bank is now losing around $1bn per week. In 2023 the Fed is likely to turn in its first annual operating loss since 1915.

The Fed is not unique, however. All major central banks have haemorrhaged enormous mark-to-market losses over the past year. The Swiss National Bank is sitting on paper losses of $143bn. The Bank of England’s hole is over $200bn. At the Bank of Canada, it’s $26bn. Some estimate the ECB’s loss around $800bn. Most are also operating at a loss. And as the governor of the Dutch National Bank spelt out in a letter to his Ministry of Finance, losses are especially acute where credit quality is high:

In normal times, most central banks remit their profits to their finance ministries. Amid losses, many have now stopped paying those dividends. Daniel Gros from the Center for European Policy Studies therefore argues that it is now clear that QE was “a colossal mistake” that “carried serious fiscal risks, which are now being realised as interest rates rise”. Is that true though? Those fiscal risks are two-fold. First is the balance sheet risk: the bonds that central banks hold have plunged in value. The second is an income statement problem: central banks are sustaining operating losses. In both cases it’s reasonable to wonder about the risks these losses portend for the taxpayer. But, upon closer inspection, it looks like . . . none of it matters? Take the balance sheet issue. As the Fed itself points out, since the securities in the SOMA are held to maturity, it doesn’t matter if they are underwater when marked-to-market:

The Fed reports mark-to-market losses for the sake of transparency, but in practice employs amortised cost accounting (not the GAAP accounting that corporations use). The Fed books bond prices at the level they were bought, plus or minus their pull-to-par — typically very small for the investment-grade bonds that the SOMA is stuffed with. The Fed is only very rarely a seller of bonds before maturity; it doesn’t face margin calls and it shrinks its balance sheet by letting securities mature, not by selling them. Those huge mark-to-market losses? They’re never actually realised. But what about that massive (fiscal) sucking sound from the Fed’s negative net income? As the boffins at Brookings have written, there are three reasons recent Fed losses are not a net burden on the taxpayer (FTAV’s emphasis below):

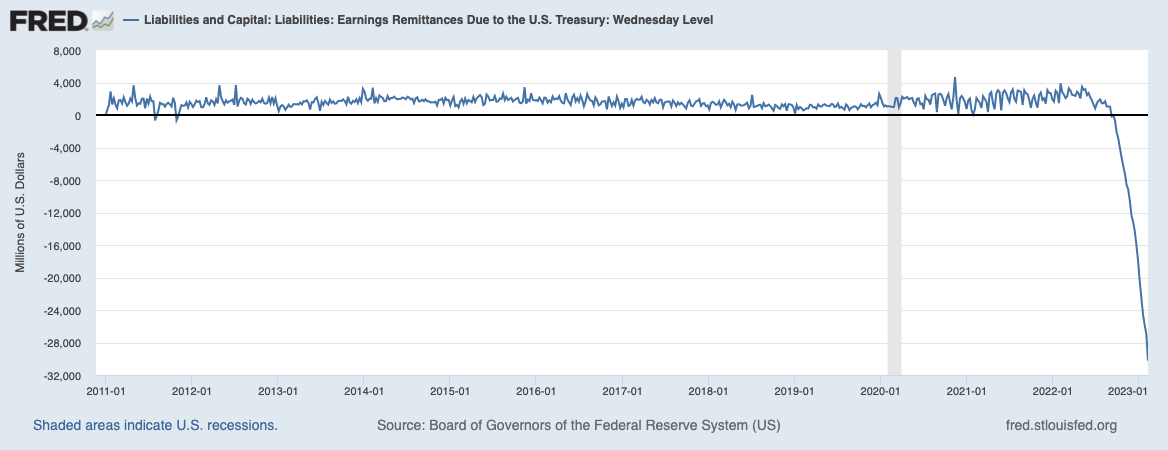

In other words, although it is fun to imagine central banks as big dumb bond funds, they’re not. And it is silly to look at any losses now in isolation from profits they made in other years. The data bears this out., Even when looking only at the profits the Fed remits to the Treasury — and ignoring the broader macroeconomic benefits — the Fed has racked up operating losses of $24bn since August 2022, but earned the Treasury $869bn in the prior decade. It’s obviously not a great look for the Fed to approach Congress cap-in-hand to ask for funding, most of which goes towards paying commercial banks interest on their reserves. The creative accounting also renders this kind of a non-issue. In times like these, when the Fed is sustaining losses, it merely sweeps these into a “deferred asset”, a kind of IOU to the government. From the Financial Accounting Manual for Federal Reserve Banks:

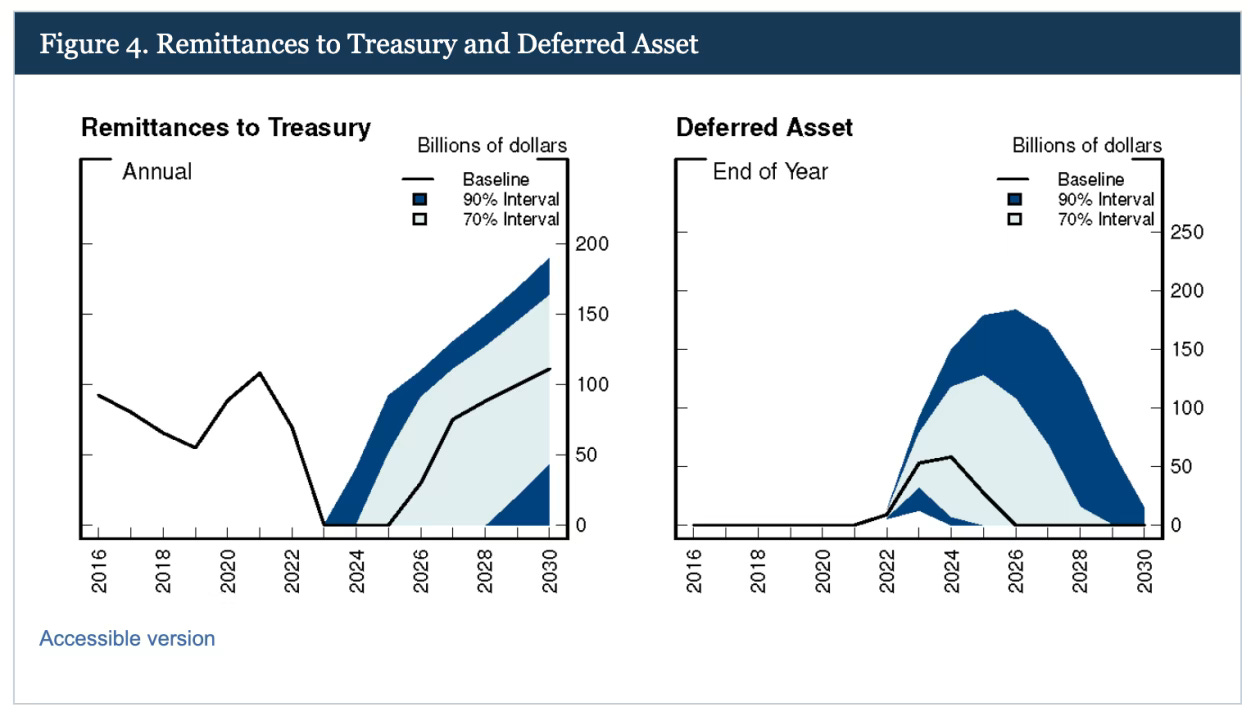

That’s not to say there is no fiscal angle here. Although this IOU doesn’t factor into the calculation of the federal deficit, the government will have to find new revenue to replace the erstwhile remittances from the Fed. But as the Fed income moves into the red, the payments don’t reverse direction: the central bank won’t receive payments from the Treasury, it will cover its operating losses via increases in reserves (AKA “printing money”). The inflationary impact of all this money printing is sterilised, since the “deferred asset” needs to be extinguished by future income. The Fed forecasts that this will happen in 2026. There are two things to note at this stage. First, not all central banks operate this way. In the UK, for example, the BoE’s losses on its Asset Purchase Facility (APF) are indemnified by the Treasury, and payments are a two-way street — the direction of flows depend on whether the APF is operating at a profit or a loss. As of November 2022, the UK Treasury had sent £11bn to the central bank to cover the facility’s losses. Second, there are theoretical scenarios where this creative accounting gets out of hand. Looking at the Fed again, one could imagine losses ballooning and the deferred asset metastasising to such a degree that the Fed has to flood the system with reserves. That could push the central bank into a doom-loop of ever-higher interest payments to depositor banks. This would, at the very least, impinge on its ability to carry out monetary policy. However, for an institution that’s typically levered with gobs of free money ($2trn of currency in circulation and rising), it is an incredibly unlikely danger. As Robert Hall and Ricardo Reis argued back in 2015: “The risks to financial stability are real in theory, but remote in practice.”

So, the SOMA’s market value doesn’t matter, since it’s all held to maturity. And, absent a need to remit funds to the Treasury, the Fed’s operating income losses also don’t matter. As an investor, the Fed is essentially a closed-end fund operating with leverage so cheap it would make a hedge fund manager’s weep with envy. These structural advantages mean it is usually highly profitable. But because the Fed also has a wider mission — and a monk’s indifference to profits — it will sometimes suffer huge losses. In the Fed’s own language:

In other words, the Fed’s mission is to maximise employment and safeguard price stability. If that entails the central bank buying a truckload of bonds right before a generational sell-off — losing a trillion or so in the process — so be it. |

Older messages

Where are all the workers?

Monday, February 13, 2023

Quiet quitting? The Great Resignation? The best explanation for the shortage of workers is retiring baby boomers.

And now, a cartoon about monetary policy

Tuesday, February 7, 2023

In pricing-in an end to rate hikes, investors push that day back

The Uneasy US Housing Stalemate

Wednesday, February 1, 2023

Affordability is bad, but a bust is unlikely

Why are we always unprepared for recessions?

Thursday, January 27, 2022

When the economy sputters, stimulus should kick in automatically

Social media is the best and the worst

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

My New Year's experiment based on the empirical evidence

You Might Also Like

6 Most Common Tax Myths, Debunked

Saturday, March 8, 2025

How to Finally Stick With a Fitness Habit. Avoid costly mistakes in the days and weeks leading up to April 15. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY Six of

Weekend: My Partner Can’t Stand My Good Friend 😳

Saturday, March 8, 2025

— Check out what we Skimm'd for you today March 8, 2025 Subscribe Read in browser Header Image But first: this is your sign to throw away your old bras Update location or View forecast EDITOR'S

Your Body NEEDS to Cardio Row! Here Are Some Options.

Saturday, March 8, 2025

If you have trouble reading this message, view it in a browser. Men's Health The Check Out Welcome to The Check Out, our newsletter that gives you a deeper look at some of our editors' favorite

What Do You Really Need?

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Is opposing consumerism lacking gratitude? ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

“Otway” by Phoebe Cary

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Poet, whose lays our memory still / Back from the past is bringing, ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Cameron Diaz Returned To Fashion Week In A Fabulous Little Red Dress

Saturday, March 8, 2025

WOW. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 3.7.2025 Cameron Diaz's Asymmetrical Red Dress Lit Up The Stella McCartney Fall 2025 Show (Celebrity) Cameron Diaz Returned To Fashion Week In A Fabulous

5-Bullet Friday — Breaking the Sperm Bank, D-Cycloserine, Tools for Grumpy Elbows, and Wisdom from Seth Godin

Saturday, March 8, 2025

“If you're feeling creative, do the errands tomorrow. If you're fit and healthy, take a day to go surfing. When inspiration strikes, write it down." ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Inside Alex Pereira's Training for Saturday's UFC 313 Showdown

Friday, March 7, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE Inside Alex Pereira's Training for Saturday's UFC 313 Showdown Inside Alex Pereira's Training for Saturday's UFC 313

Update Your Android Devices Now 🚨

Friday, March 7, 2025

This TikTok Cleaning Method Might Have Broken My Fan. The security update includes fixes for two zero-day exploits. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY

EmRata's Itty-Bitty Bikini Just Brought Back This "Cheugy" 2010s Trend

Friday, March 7, 2025

Plus, everything you need to know about Venus retrograde, your daily horoscope, and more. Mar. 7, 2025 Bustle Daily New books from Emily Henry, Karen Russell, and Kate Folk are among Bustle's best