Figuratively speaking, the mind is the reflection the brain sees when it looks in the mirror.🧠 This is the fourth article in a series of philosophical musings on the mind and the brain. Read them allThe mind is the entity which experiences our mental life, and the brain is our 'central processing unit' which generates that experience. While we know that the brain functions through electrochemical signals passing along nerve fibres and across synapses, the functioning of the mind is a bit of a mystery. Some scientists and philosophers maintain that the brain and mind are two sides of the one coin. But they are silent on what exactly is on the mind side. What medium carries all those thoughts we have? Will it remain after the brain dies?

The brain does a perfectly good job running our complex bodies. It regulates our heartbeat and breathing, without any help from our conscious minds. Why should it not run the whole show alone, including our complex interactions with the world and each other, without help from a mind? Perhaps it does. Maybe the mind is just an illusion, as claimed by materialists. They make this claim because they have not been able to reduce mind to anything physical - only a physical entity can interact with the physical world, they believe. Yet, why did evolution provide us with a mind if it is only an illusion?

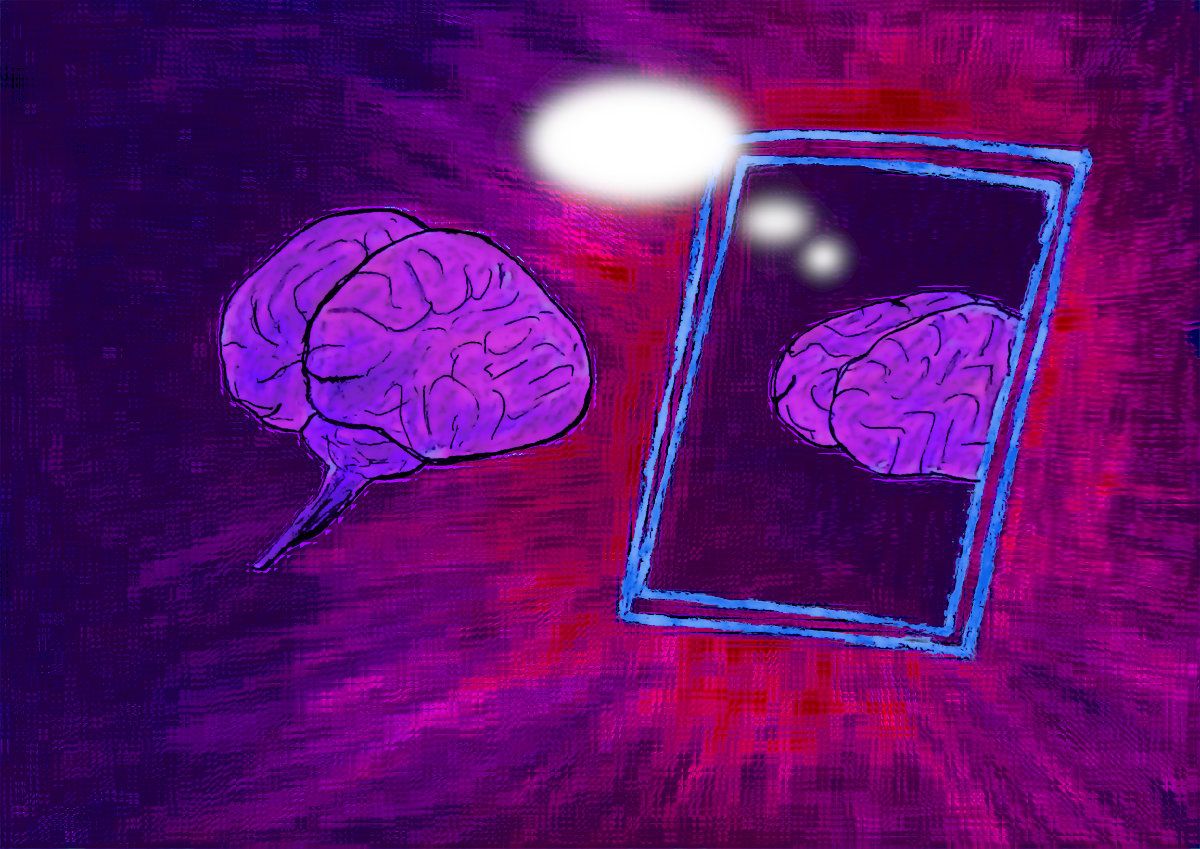

The mind must have had some survival function; otherwise it would not be there. In the previous article, I put forward the idea that the mind is the result of self-observation by the brain, with respect to its own activity and its interaction with the world. Figuratively speaking, the mind is the reflection the brain sees when it looks in the mirror. It doesn't see electrochemical signals; it sees a mental picture or story described by those signals. Based on what we see in our own minds we infer that the same sort of things are happening in the minds of others. Evolution has equipped us with the ability to read the minds of friend and foe, predator and prey. This would have had considerable survival value; and would have been naturally selected along with the ability to read our own minds.

Arguably, the mind cannot be reduced to a physical entity because it is not physical. It is a reflection; a representation of the physical world inside the brain; a mental picture which somehow facilitates our functioning. How so? Because it is the outcome of the transformation of electrochemical signals into patterns. Our brains are superior to computers, in part, because we have the incredible ability to to recognise patterns. For example, the eye receives light of varying wavelengths from an object in the environment, and transmits this information to the brain as electrochemical signals. The brain then converts these into a representation of the object, which we see in the form of a mental picture. Utilizing this picture, the brain of early humans would have had an enhanced ability to, say, recognize predators hidden in the bushes. This faculty would have been naturally selected during evolution as it has a high survival value. What's more, we might expect this pattern-recognising ability to also work for non-visual patterns generated by the other senses and internal thoughts.

We may better appreciate what mind is if we go back along the evolutionary tree to primitive life forms. Even a single-cell organism, such as an amoeba or bacteria, has an awareness of its position in relation to its environment. It will react to a stimulus: it will withdraw from a harmful heat source, on the one hand, and detect and approach its food, on the other. Yet it has no brain! It behaves this way in order to survive because evolution has equipped it so. When a single-cell organism receives a stimulus from its environment, this gives rise to a message generated internally, inter alia, to avoid danger or to approach a food source. So, in its most basic form, awareness is a message requiring some action by the organism to ensure its survival. While its transmission is a physical phenomenon, the content of the message is not.

Could this stimulus-response awareness be the evolutionary precursor to conscious mind in higher animals and humans? In such case, its origin is the will to survive possessed by all living organisms, elaborated through the process of natural selection during evolution. As such, the ultimate origin of conscious mind can be found in the nature of life itself. Conversely, life's ultimate achievement was to enable conscious mind, which we humans all get to experience. In higher animals such as humans the awareness message is in the form of a mental picture or story, as we have a much richer life and a complex brain capable of generating such a message. Mental pictures and stories carry meaning, are not physical, and hence cannot be reduced to a physical base. If the conscious mind did indeed originate from the will to survive possessed by all living organisms, then attempts to create an artificial conscious mind from silicon circuits may end up being futile. That is, unless the engineers are able to instil the will to survive in their machines. Many AI researchers assume that consciousness will just emerge from within computers once they approach the complexity of the human brain. We will just have to wait and see.

How can we reconcile the model for the mind herein with the conviction we have that our minds call the shots? This conviction would seem to violate the scientific maxim that a non-physical entity such as a mind cannot cause action in the physical world. Any physical action must have a physical cause. Actually, our model for the mind does not violate this law. As argued earlier in this article, the brain creates the mind through self-observation of what is happening within its circuits: not the electrochemical signals, but the mental pictures and stories they describe. This is the mind. Based on this virtual picture, the brain optimizes its decisions and implements them. the mind is the alert; the brain does the work. Thus, only a physical entity - the brain - interacts with the physical world. No law of physics is violated. The mind feels involved and thinks it is initiating the action, but in fact it is the underlying brain which does so.

Given the above, do we have free will? The answer is…kind of. While there are many instinctive reactions to the environment, where the brain acts like a pre-programmed robot, such as the fight or flight reaction to danger, something different happens when analysis is required before any decision. In such case, the brain relies on the mental picture it creates in the mind to optimize its decision. So, the brain has a choice in the action it takes, depending on what it sees in the mental picture in the mind. This picture may be biased by internal factors. Mood swings and attacks of conscience, for example, could affect the mental picture, and thus any decision taken by the brain. While the propensities to have such experiences of mood and conscience may have been put in our heads by factors outside our control, once there they are ours to own.

To summarize the case herein: arguably, the evolutionary origin of conscious mind can be traced to the "will to survive" possessed by all living organisms, and ultimately to the nature of life itself. At the beginning, this "will" took the form of primitive awareness in single-cell organisms. As evolution progressed and organisms developed complex brains, this awareness took the form of mental pictures or stories. These reached the ultimate in richness and detail with the advent of the human brain. This brain has the ability to look inside itself and transform the electrochemical signals it finds there into a dynamic pattern or story which it projects internally as the mind. The clarity of this pattern or story enables the brain to make better decisions than otherwise would be the case. Conscious mind is a legacy from evolution which serves a purpose: it is not an illusion. That aside, life is a hell of a lot better with it than without it.

The Editors' Bookshelf Dee Lan

Welcome to The Editors' Bookshelf where you get weekly book recommendations straight from our editors! This week, we have Dee Lan suggesting The Honjin Murders by Seishi Yokomizo. When you purchase a book through our Bookshop.org link, we earn a small commission. November 25th 1937 was supposed to be a joyous occasion for the Ichiyanagi family. However, what was supposed to be a joyful wedding night quickly turns into a sinister mystery when the head of the family and his bride are brutally murdered. It is an interesting locked room mystery, and the resolution is satisfying. What also adds onto how interesting the book is the usage of repeating elements - namely a koto, a traditional Japanese instrument. Yokomizo also uses vivid descriptions, so it’s easy for someone who is not Japanese to visualise elements in the story. The story had me on the edge of my seat as I followed the young detective Kosuke Kindaichi, and observing how he cleverly figures out the murderer as well as the murder method. Another thing that helps with immersion is references to real-life authors, which allows for the book to feel more sinister. If you’re an avid murder mystery reader looking to expand your horizons, then definitely check this book out.

🏹 Your favourite author × Snipette? We're guessing you read many interesting things besides Snipette—and that's where you can help us! If you find an author or article you think would match our style, drop us a tip and we'll follow through to see if they're interested in a collaboration.

|