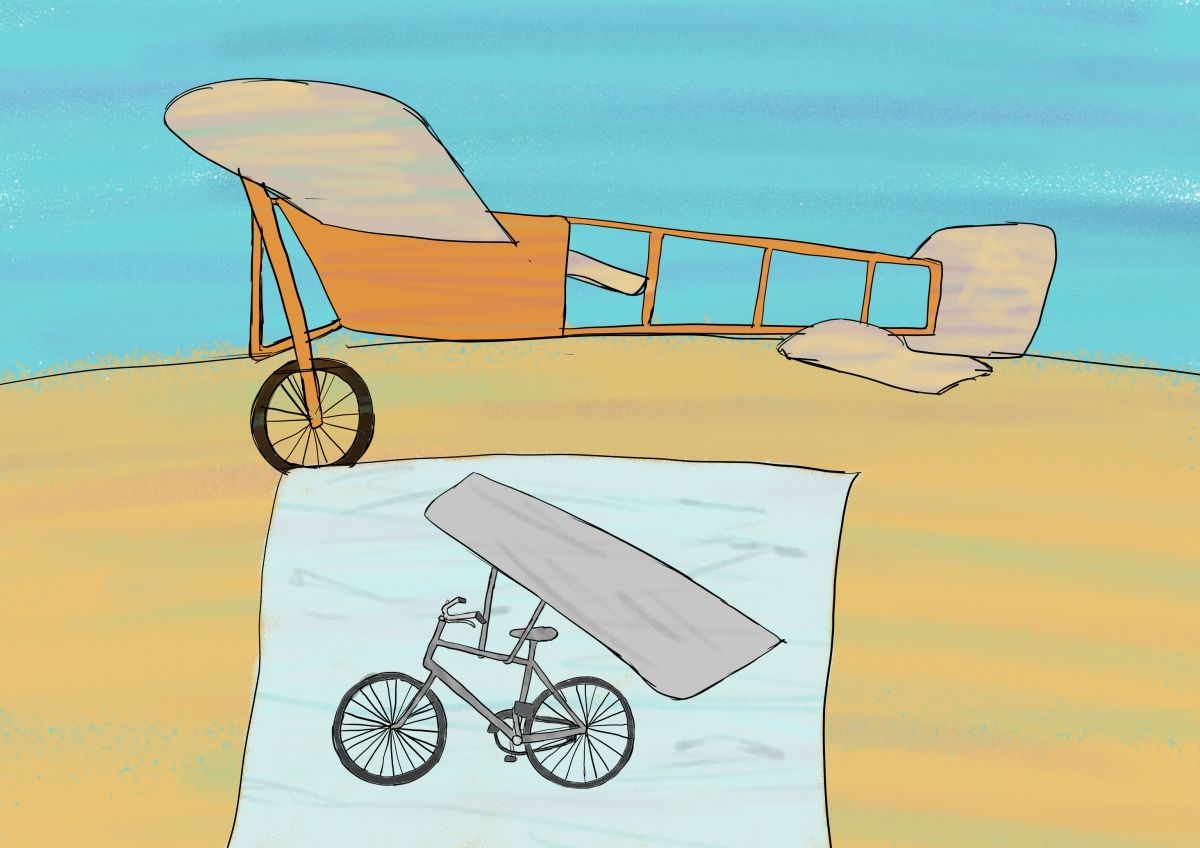

Snipette - Taking Flight

|

Older messages

Purely out of Language

Friday, May 19, 2023

Language can influence the way you think. But do robots think? Snipette Snipette Purely out of Language By Badri Sunderarajan – 19 May 2023 – View online → Language can influence the way you think. But

Graffiti

Friday, May 12, 2023

The words of the prophet are written on the subway walls. Snipette Snipette Graffiti By Reva T. – 12 May 2023 – View online → The words of the prophet are written on the subway walls. One of my

Mouse with a Human Ear

Friday, May 5, 2023

Fixing machines is easy; fixing living creatures is hard. Or is it the other way round? Snipette Snipette Mouse with a Human Ear By Thakshila Wijesinghe – 05 May 2023 – View online → Illustration

WhaleGPT

Friday, April 28, 2023

AI can work wonders with human language. Can it also help us talk to whales? Snipette Snipette WhaleGPT By Anirudh Kulkarni – 28 Apr 2023 – View online → AI can work wonders with human language. Can it

Extraterrestrial Heaven

Friday, April 21, 2023

Can we rebuild to have innovation without bureaucracy? Snipette Snipette Extraterrestrial Heaven By Avi Loeb – 21 Apr 2023 – View online → Can we rebuild to have innovation without bureaucracy?

You Might Also Like

• Book Series Promos for Authors • All in one order • Social Media • Blogs

Wednesday, January 15, 2025

~ Book Series Ads for Authors ~ All in One Order! SEE WHAT AUTHORS ARE SAYING ABOUT CONTENTMO ! BOOK SERIES PROMOTIONS by ContentMo We want to help you get your book series out on front of readers. Our

🤝 2 Truths Every Biz Buyer Should Know

Tuesday, January 14, 2025

Plus 1 Game-Changing Idea for SMB Acquisition Biz Buyers, Welcome to Main Street Minute — where we share some of the best ideas from inside our acquisitions community. Whether you're curious or

Artistic activism, the genetics of personality & archeological strategies

Tuesday, January 14, 2025

Your new Strategy Toolkit newsletter (January 14, 2024) ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Reminder: B2B Demand Generation in 2025

Tuesday, January 14, 2025

Webinar With Stefan and Tycho ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Why Some Types of Art Speak to You More Than Others

Tuesday, January 14, 2025

Your weekly 5-minute read with timeless ideas on art and creativity intersecting with business and life͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

How Chewbacca Roared a Woman into New Teeth

Tuesday, January 14, 2025

It started as a prank. A funny, and mostly harmless one -- annoying, sure, but most pranks are.

🧙♂️ [SNEAK PEEK] Stop giving brands what they ask for…

Tuesday, January 14, 2025

Why saying “no” could actually be your smartest move ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Book Promos • SIX posts each day on X.com • Over 33 days •

Tuesday, January 14, 2025

Tweeted 6 times daily for 33 days only $33 Logo ContentMo Tweets Your Book to Our Twitter Followers Each Day We TWEET Your Book for 33 Days, 6 Times/Day = 198 tweets SEE WHAT AUTHORS ARE SAYING ABOUT

The Ad. Product Backlog Management Course — Tools (4): GO Product Roadmap and the Now-Next-Later Roadmap

Monday, January 13, 2025

The 25000 Feet Level of the Course's Alignment Model ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Using this free CRO tool?

Monday, January 13, 2025

Improved insights, results and workflow. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏